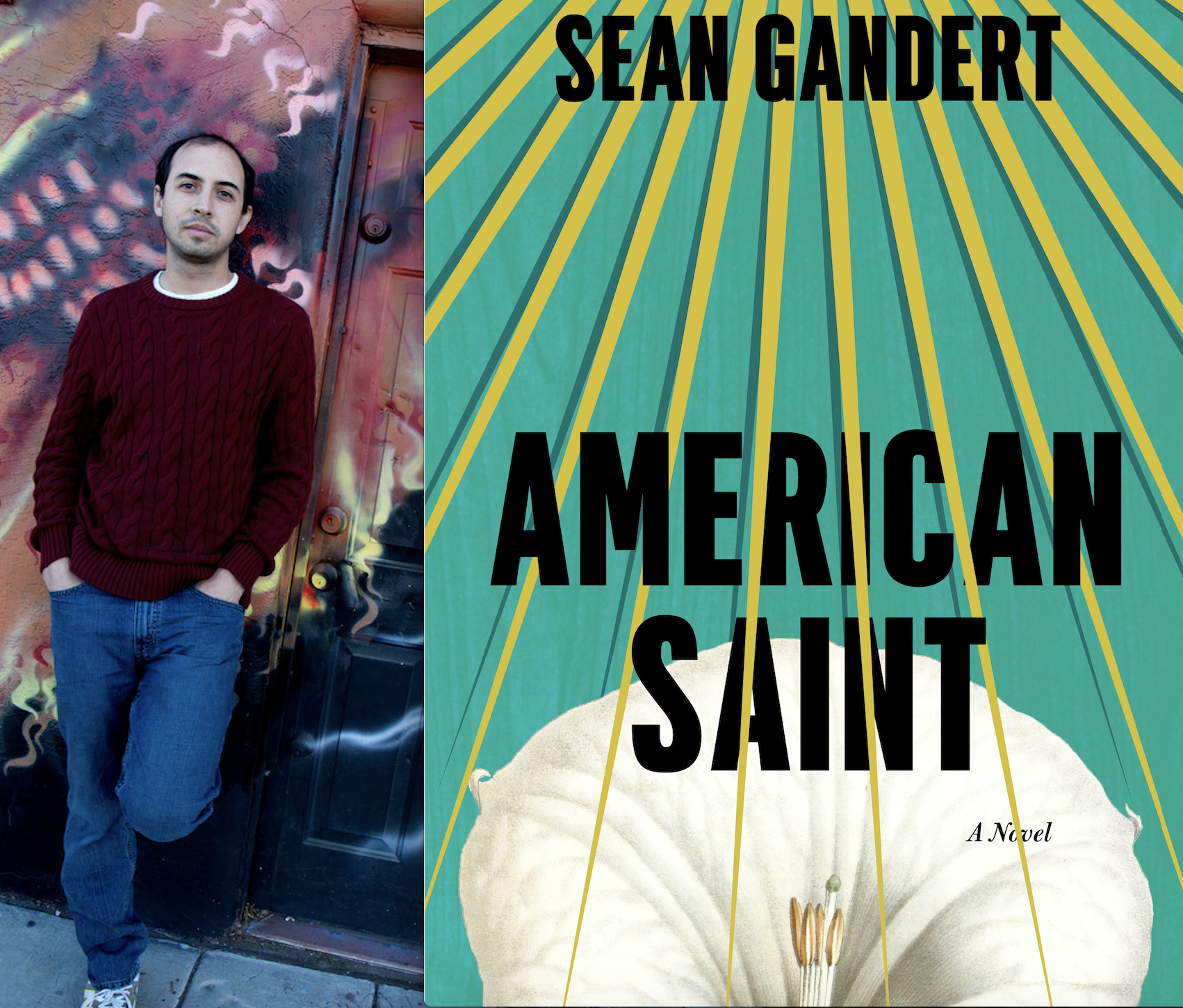

Set in Albuquerque and steeped in magic and Catholicism, Sean Gandert’s novel American Saint uses the perspectives of a myriad of witnesses—unreliable or not—to sketch a portrait of Gabriel Romero. Raised by his mother Isabel, and his devout Catholic curandera grandmother, Gabriel develops what many believe are rare healing gifts. Unable to fall in line with the Catholic Church, Gabriel founds his own congregation, where he performs healing rituals and mobilizes his congregants against oppressive state and corporate forces. Gabriel is catapulted to both folk saint status and tabloid fame, and even captures the interest of the FBI. I spoke with Sean Gandert about brujeria, faith, con artists, and writing politics into fiction.

Katherinna Mar: Isabel Romero’s mother is a curandera, and Isabel constantly emphasizes that her mother is a curandera, not a bruja. Brujeria and witchcraft are experiencing a resurgence in pop culture, and I think, in a more positive light than in the past. I’d like to hear more about the cultural take on the difference between what makes a curandera and what makes for a bruja. And how does the stigma against brujas in New Mexico compare to the stigma against witches in say New England? Did the Catholic Church deal with witches differently than the Anglo Protestant Church? Did the Catholic Church treat curanderas and brujas as one and the same?

Sean Gandert: I think a lot of this is a generational thing, but it also ties in with the religious part of healing rituals. Curanderas could still be very faithful, very Catholic, but brujas are supposed to be in league with the devil. At least, that’s the theory–in reality, I think a lot of the time it was that if you knew someone personally they were a curandera or curandero, whereas if they were unknown, a healer from another village for instance, they’d be thought of as a bruja or brujo. I think the recuperation of brujeria by writers like Ana Castillo and Gloria Anzaldúa was an important part of questioning the received wisdom a lot of us had about what, exactly, a bruja is.

The Catholic Church has always had issues with brujas because of their relationship with indigenous culture–her resistance to the effects of colonization is what made her become synonymous with the devil and evil. In essence, women who wouldn’t conform to colonization became brujas as a way of ostracizing them. Curanderas could be seen as a more syncretic way that indigenous and Spanish cultures collided, combining Spanish faith with indigenous rituals and beliefs. That being said, I’m unfamiliar with any particular violence directed towards brujas–growing up, it was always more of a “stay away from that person” sort of thing.

In any case, the relationship between curanderas and brujas is complex enough that I worry about saying anything too definitive. I end up thinking about Luís Alberto Urrea’s The Hummingbird’s Daughter and the way its protagonist Teresita is a curandera… up until she needs to be controlled, at which point she’s branded a bruja. This, I think, is the reality of how these terms usually work. When Isabel calls her mother a curandera, it’s because she wants to control the narrative and not allow the story of her mother, or her son, to be used by the patriarchal Church against her, and she knows how easily the identity of the benign curandera can drift into the malevolent bruja through no fault of her own.

Katherinna Mar: So the protagonist of American Saint is Isabel’s son, Gabriel Romero. He grows up surrounded by curanderismo, eventually becoming, among other things, a distinctive healer. Growing up, he is also very interested in learning magic tricks—the art of illusion. Is there a key distinction for you between curanderismo and this type of performance? In what ways did these forces in Gabriel’s life work together to make him a folk saint?

Sean Gandert: Gabriel’s fascination with both curanderismo and illusions are related to his growing understanding about the power of belief. Which is not to say that curanderismo isn’t real, but rather that all healing is to a certain extent faith-based, including western medicine. What distinguishes these forms of belief in particular from the more passive things we believe in without even thinking is that we want to believe in magic, or healing, or faith. This form of belief is an active process, requiring a certain amount of participation from the believer.

Sainthood, folk or otherwise, is a strange thing, as it requires a performative aspect that in some ways cuts against what we would normally think of as saintliness. For Gabriel, this comes entirely from magic, an understanding that showmanship is just as important a part of belief as the reality we experience with our senses. Conversely, curanderismo usually tends to be quiet, remedios offered to neighbors or acquaintances for altruistic purposes. But there’s only so many magic tricks, making all magicians more or less the same, so what distinguishes who gets paid and who doesn’t is dependent on who puts on the best show.

Katherinna Mar: Would you talk about Los Hermanos Penitentes and why they played a large role in your novel?

Sean Gandert: I was thinking about alternative forms of Catholicism, ways of belief that lack the centralized and dogmatic views of the Church at large. Los Hermanos have always focused strictly on the community they’re from, and no two sects are alike, because no two towns or villages are alike in their needs. Catholicism has an extremely violent history, but Los Hermanos push that violence onto themselves rather than others in their attempt to live in a truly Christlike manner. Because they’re secretive, they don’t proselytize, and their focus remains on charity rather than wealth or power. Some groups no longer restrict membership by gender, too, which truly breaks down the patriarchal and somewhat fascistic hierarchy of the Church. With all of this in mind, they became a model to me for how a community can use faith for productive, rather than destructive, ends. I think the violence of Los Hermanos has always put off Anglos because the idea of enacting violence inward towards themselves, rather than outward against some othered enemy, feels antithetical to how religious violence has played out through most of history. Part of Manny’s journey as a character is to understand that this violence committed with consent as a sort of devotion is a completely different matter from that of, say, the police he protests against.

The other, less intellectual answer is that I’ve been interested in Los Hermanos since I was little, and unfortunately they’re dying off. I remember hearing about them from my grandparents when I was young, though only little bits here and there, and writing American Saint gave me an excuse to visit the Hermanos and speak with members while that’s still possible. My representation of them is done with the utmost respect, and I hope they continue worshipping with their communities for many years to come.

Katherinna Mar: Your first book, Lost in Arcadia, was a semi-dystopian novel set in the very near future (2037), in a country with a border wall decked out in advertisements and a demagogue president who eerily resembles Trump (though he did have much better manners). I know that book was many years in the making, so it was fascinating to see it come out right around the time of the 2016 Presidential Elections. It was fascinating because none of it seemed terribly far off–it might as well have been set in 2016.

Sean Gandert: Originally, Lost in Arcadia was set in 2029, it just took so long for me to finish and get it published that I had to bump up the timeline, though its version of the future was always very much about what’s happening today. Now that it’s been out for a couple years, I feel somewhat prescient about the book, as a lot of what I predicted has unfortunately come to pass, though also more than a little naive. My thinking was that a person as malevolent as Trump was on the way to being elected, but they’d have to be savvy enough to at least pretend at not being a complete idiot and asshole.

Last year I taught a unit about Trump in a course on con artists, and one thing that really distinguished him from the prototypical model was his stupidity. I’m fascinated by con artists, and consider them to be the heart of what has made America what it is today, the American Dream a con that’s stretched on for centuries, but I was thinking about what’s worked for cons in the past, and that usually means keeping at least some basis in reality. How basic and obvious Trump and the Republicans’ lies can be while still remaining completely effective for tens of millions of people speaks volumes about our country.

Katherinna Mar: This book however is very grounded in the present-day: we see the ACLU getting down with White Power Greg about free speech, a massive indigenous-centered and led pipeline protests a la Standing Rock, incredible police violence, Black Lives Matter. I’m curious about the shift from near-future to what is basically today. Would you talk about how your sense of urgency may have changed?

Sean Gandert: Writing that takes place in the near-future is always about responding to the present in an oblique way, and I like how it allows you to stretch reality out satirically to defamiliarize what’s happening, but I did feel like I needed to write something with more immediacy. I used to be a lot more concerned with issues I saw on the horizon, trickling problems in society that seemed ready to transform into a massive flood, but now it’s hard to argue that the flood hasn’t already arrived. So the question we’re left with is what do we do right now? What’s the appropriate response to what’s happening?

The protests that take place near Española in the book are more a projection of how I wish things would go than anything that’s taken place in the state. Water rights in New Mexico have been a constant issue in the area for hundreds of years, but I’m often surprised by how little fight we give. The area my dad’s family comes from, Mora county, passed a ban on oil and gas development in order to protect its water from pollution that’s occured in many other parts of the state, but after being sued the community’s ordinance was overturned. Local residents are still fighting, but it’s a quiet one that you rarely hear about even locally. Standing Rock was inspiring and I was thrilled that the water protectors were able to get their fight into the national consciousness, but unfortunately in the end the corporations always seem to win. The sad fact is that companies have more rights than people, let alone the environment. I wish we would do something to change this, for instance looking to examples like in New Zealand where the Te Awa Tupua river was granted the same rights as a person. But then again, we currently have concentration camps overflowing with refugees and police murdering black men with zero accountability, so if we’re unwilling to enact even basic human rights, the idea of environmental rights seems like a pipe dream.

Katherinna Mar: There’s more than a touch of magical realism to this book, with Gabriel being many places at once, performing miracles, magic tricks. It’s interesting — a lot of the magical elements are tempered with conspiracy theories, subreddit conversations, and History Channel debunking. There are also so many perspectives presented—some cynical, some unreliable—on what he did or didn’t do, it’s really up to the reader to decide whether this is a magical world or not. And I really liked being offered the choice, and in this particular way. Do you want to talk about this balancing act? The craft of it?

Sean Gandert: From a craft standpoint, the biggest difficulty for me was making sure readers understood that characters contradicting each other wasn’t a mistake on the part of the author. This, it turns out, is harder than it seems. On film, I think this is easier, as reality is so concrete on the screen in front of us, but on the page I found that I needed to make this idea more obvious than I originally wanted to. When discrepancies were small, they felt like errors, but if they were glaring it became clear that this was intentional, which is the opposite of how most aspects of how writing works.

As to why this felt important, the idea of an omnipotent narrator always seems false to me because that’s not how the world works. We constantly have to decide what we believe in, whether that’s faith, conspiracies, what’s written in our history books, or what we read in newspapers. Narratives that get rid of this part of the world erase some of the complexity of existence in a way that feels false to me.

Likewise, I really love leaving things up to the reader, making them an active participant in the narrative rather than passively reading something without reflection. I know from Amazon reviews of Lost in Arcadia that this is not at all to everyone’s taste, and there’s certainly a place for spoon feeding narratives, but to me one of the most interesting things a story can do is refuse to offer easy answers. I’ve been asked, “What really happened? Did Gabriel perform miracles?” and it’s a question I don’t want to answer because I want to leave that for every reader to decide.

Katherinna Mar: I notice the book uses the term Hispanic a lot, as opposed to Latinx, which seems like the more widely accepted term at this point. One of the characters in the book asks if a particular dance is Native American or Hispanic. While the grandmother seems like she might be indigenous (her healing practices specifically), Gabriel is Hispanic. I’m curious about the regional specificity of these terms, and how colonization by first the Spaniards and then USians might make for a different set of vocabulary regarding ethnicity and indigeneity.

Sean Gandert: Within New Mexico, and I suspect many other areas colonized by the Spanish, there has always been a ton of emphasis placed on Spanish roots, and linked with this is plenty of colorism and racism against indigenous cultures. Thus, the term I grew up with, Hispanic, places an emphasis on this part of our identity. I certainly understand why a lot of us bristle against the word, but it’s usually the one that comes first to my tongue, and because most characters I wrote about are from the same location as me and are my age or older, I had them use this as well unless there was a reason not to. In reality, it’s not uncommon to hear the same people refer to themselves as Mexican, Chicano, Mexican-American, Nuevo Mexicano, Hispanic, Latino, Latinx, or many other terms depending on the context, but given the book’s interlocutor I think this is the word that would be used.

In that section you mention about the Matachines dance, a character says that it may be a Genízaro (enslaved indigenous people raised in Spanish colonies as servants) ritual, and I wanted to make sure they weren’t left out of the book because they’re an important part of the area’s history that rarely gets mentioned. But just a few months ago I heard about a prominent New Mexican scholar claiming that Genízaro never even existed. In colonized areas, racial and ethnic categories only seem simple to outsiders, when in fact people are always trying to renegotiate with society at large as to how they should be treated.

Katherinna Mar: We touched on this briefly during our call this morning, and I wonder if you would want to expand on what it means to be a writer while the world is burning.

Sean Gandert: I wonder if the real question is, what does it mean to be a person while the world is burning? I do think that right now the type of writing we need is more active, more aggressive, more pointed than usual, but writing rarely changes the world. It can be a form of activism, and I think of art as an intrinsic social good and that’s certainly valuable, but the struggle for everyone right now is to consider what you can actually do and do it. If you’re disenchanted and feel complete malaise for society right now, remember that this is what keeps the status quo in power, and it’s this status quo that continues to destroy the world. For writers and artists of all kinds, I think this is the issue as well, and that our challenge is to think outside of the complacent narratives that we’re given and look for something else. Something as simple as upending a cliche is a tiny revolution, and there’s a value to this however insignificant it can sometimes seem.

American Saint will be released on August 20 and is available for preorder here.

Sean Gandert is the author of the novels American Saint and Lost in Arcadia. Born and raised in Albuquerque, New Mexico, he has an MFA in creative writing from Bennington College. A freelance writer and college-English instructor, he currently lives in Florida with his wife and an increasingly large pride of cats.

Katherinna Mar is a genre-fluid writer from Chicago. She received an MFA in fiction from Bennington College and was a Peter Taylor Fellow at the Kenyon Review Writers Workshops in 2018. She is currently an MFA candidate in poetry at Virginia Tech.