I read Carmen Maria Machado’s new memoir In the Dream House in a day. It’s feverish, urgent, and full of new ways of thinking about queer violence, love, solitude, domesticity, structures both in writing and in life, drinking, fucking, graduate school, writing, and thank god, bisexuality. I was not in charge of the reading of it, so much as it read me.

Structurally, the book is a marvel and there’s no way I can do it justice in this review. Each chapter or scene begins with the title “Dream House as…” Some of my favorites include, “Dream House as Road Trip to Savannah,” “Dream House as Queer Villainy,” “Dream House as Epiphany,” “Dream House as Ambiguity,” and “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure.” Some might call the book a fragmented memoir or a meta-memoir; it wears its structure out loud and is piece-y (as some haircutters like to say). It’s really a very smart memoir, in which Machado, at full writing prowess, makes use of every text—personal experiences with her emotionally abusive unstable first girlfriend, queer theory, movies, music, novels, short stories, music videos, fairy tales, religion, animals, court cases, data on domestic violence, and previous research on queer domestic violence, which is fairly scant. This pulling together of such a variety of evidence—from personal to research is what all good essayists and memoir writers do. As writers, we use every text available to us to understand a problem.

The problem in this book is queer violence—woman on woman—and how it’s excused and housed in the frames of lesbian erotica, pulp fiction, movies, utopian visions of lesbian love, and the domestic structure of the house itself. The house, for Machado, is a metaphor for dreams, containments, texts, and violence, but she also, as a self-described Cancer, uses the actual house she and her ex-girlfriend inhabited as the stage, the site, the landscape for both the domestic and the all too real. What if you get the Barbie dream house and it turns out to be haunted? What if you find the cottage and there’s a witch inside of it? What if your house isn’t your house at all, but a trap you’ve been tricked into thinking you love? What if you love your house, but your partner is terrifying? What if you both love her and hate her?

Machado writes, “Fantasy is, I think, the defining cliché of female queerness. . . All of this fantasy is an act of supreme optimism, or if you’re feeling less charitable, arrogance” (109), and in the beginning of the book, in the “Dream House as Prologue” she acknowledges, “The abused woman has been around as long as human beings have been capable of psychological manipulation and interpersonal violence,” and still Machado asks us to consider “domestic abuse between partners who share a gender identity” (5).

What’s tricky about abuse is that sometimes it leaves no physical marks and this is true of Machado’s relationship with her unnamed ex. What begins as a flirtation and foray into ethical non-monogamy turns into a full-fledged relationship, monogamous, long-distance, and full of distrust, drinking, rageful outbursts, deep love and connection, fucking, a shared house, and the constant nagging feeling that Machado cannot please this person, no matter what she does.

There is a rebirth too, but I don’t want to spoil the book for you.

It will matter to some readers, like me, that this girlfriend is this first woman who has wanted her “that way—desire tinged with obsession” and her girlfriend tells her “this is what it’s like to date a woman” (45). It reminded me of the first woman I fell in love with telling me that “lesbians are mean” and that I should expect no better from them than I do from men. Many lesbians, including my first lover, have warned me that women will hurt me more than men because they are smarter and therefore can enact particular cruelties. Perhaps they were all grooming me for future wounds, or maybe trying to toughen me up, or even break any utopian fantasies that I might have as a late comer-outer to the queer party. Perhaps my first lover was schooling me in her own traumas. I can’t say because we no longer speak to one another, but like Machado, I absorbed the message that, “that lesbian relationships are somehow different—more intense and beautiful but also more painful and volatile, because women are all these things too” (45).

It matters to me as a reader that Machado identifies as bisexual, and the girlfriend as the lesbian. After 46 years of thinking I was a Gemini, I finally read my natal chart and accepted that I am a Cancer. In this same year, I came out of the closet. I don’t really love this phrase because I knew I liked all genders for a long time, but I didn’t feel I could claim bi or pansexuality until I’d had a relationship with a woman. This is something that lesbians regularly told me. You’re not queer until you’ve eaten pussy. Okay, I believed them. I certainly never want to claim something that’s not mine. I met my ex-girlfriend at a poetry reading, and afterwards we started making out in a bar, and then continued to touch each everywhere for the next four months. I fell completely in love with her, and pretty much succumbed to her every wish, until she left me.

The violence that lesbian women sometimes enact against bisexual women—for being sluts, for being traitors, for not getting it, for getting it too late, for loving men, for sucking dick, for double dealing—lurks throughout the memoir and is a big part of acceptable queer culture to this day. It’s not something I’m often allowed to talk or write about except with other bi or pan people, but I was grateful and hungry for to see it in a book. Perhaps it’s less to do with bi/lesbian relationships but more butch/femme and or dom/sub or maybe these binaries need to go (and god knows I wish they would) but they seem very much alive among a generation of queer people I see at bars and have dated and loved in this first queer year of mine. It matters too that Machado, a woman of color, is very much in thrall to this white woman, this petite powerhouse of privilege who she feared she could never have. Part of the problem of all of abusive relationships, queer or straight, is that they are housed in white racist America.

Like many of my favorite memoirs, essay collections, and recent history books—James Polchin’s groundbreaking look at how the press covered gay murders, Indecent Advances; Melissa Febos’s beautiful memoir about a lesbian love that cannot contain her, Abandon Me; and Kai Chang Thom’s sharp and funny new essay collection, I Hope We Choose Love—Machado makes visible a hidden history, her own and that of other queer women who have been abused, even if the legal system does not provide protection from forms of abuse that are “verbal, emotional, and psychological” (138). The book explores painful scenes of drunken verbal attacks, abandonment, black outs, fights, and controlling sets of rules about Machado’s body, friends, work, and freedom. Through it all, Machado attempts to make sense of her own reactions to her then girlfriend, and the larger “cliché” “fantasy” of female queerness (109). Machado hopes: “Maybe this will change someday. Maybe, when queerness is so normal and accepted that finding it will feel less like entering paradise and more like the claiming of your own body: imperfect, but yours” (109). This memoir is such a claiming, for a return to her story, her body, and her life. And just like she is in her brilliant collection of short stories Her Body and Other Parties, Machado’s writing is ravenous, sex-positive, and loving in its appetites for all bodies, all genres (whether science fiction or fairy tale or, my favorites as a kid, the Choose Your Own Adventure series), and all texts. I for one am this hungry too. I want it all and Machado gives it to me.

When a lover tells you that you cannot write about them, it’s a kind of test. What matters to you more? Me or your work? It’s an unfair question, and an equally impossible demand. To me, it’s a challenge. The man I loved before I came out, the one who left me in a drunken rage because I fell in love with a woman, who my child and I loved very much and had made a part of our lives, once tried to shame me about my essays. It didn’t go well. He later admitted to being afraid of how little shame I seemed to have. Later, my first girlfriend, also a writer, but not a personal essayist, sometimes complained that I would have the last say, and that I would betray her by writing about us. Her fear of the story I might tell of us, seemed more real to her, than anything I’d actually done. I understand that I have some power as a writer, but I also wonder about the coercive ways in which queer people, people of color, the disabled, and the marginalized are made to be silent by those that supposedly love them. I don’t buy these tactics.

Machado’s ex, after an explosive outburst in the car, when she can’t find Machado at work for an hour, yells at her, “You’re not allowed to write about this. Don’t you ever write about this. Do you fucking understand me?” (44). Isn’t this the abuser’s calling card? The priest and the doctor, the trusted adult tell the child to keep the secret. The child, the little girl or boy, listens to the threat or they tell. I’m all for telling. Because I’ve learned that secrets fester and refuse to heal, because they can’t get any air.

This past month, my ex-girlfriend and I bumped into each other at a bar and I was rattled. I hadn’t seen her for almost a year. She wrote me a long email the day after that, which included the apology I had wanted for so long. The email didn’t have any of the gaslighting I’d come to expect in the last horrible month of our affair either, still I was afraid. She didn’t tell me I had a multiple personality disorder like she’d once done. She didn’t change our plans on a dime and laugh in my face when I cried or make fun of a woman I tried to date after her, like she once did. She was in therapy now, and I was happy for that. She was lonely too, which I understood because I was also lonely.

I dithered and fretted as I tend to do. Should I respond to the email? Could I protect myself? Wasn’t I still in love with her? Did it matter? Could I make a boundary? I thought of Machado’s book a lot. It was fortification and strength. It was a pill to protect me. My ex isn’t like that, I told myself, and that was true in many ways, though there were moments of deep recognition for me when I finished the book and held it to my chest. Still I knew I needed to keep my distance. I needed to say No, as we all do, every day right now. NO. NO. NO.

I wrote most of this essay from Belfast, Maine, staying with my very dear friend and her ethically poly family. For the first week, we stayed in the ex-husband’s lovely apartment, which is a dream house for me, with its old wooden floors and shady front porch, framed by fiery orange tiger lilies. I have many dream houses, almost everywhere I go I find a couple. During my second week in Maine, I’d found a small cabin on the ocean that I very much wanted to buy. I don’t have the money yet, but I was finally allowing myself to dream of my own house, a place for my kid and myself, and our cat and no one else.

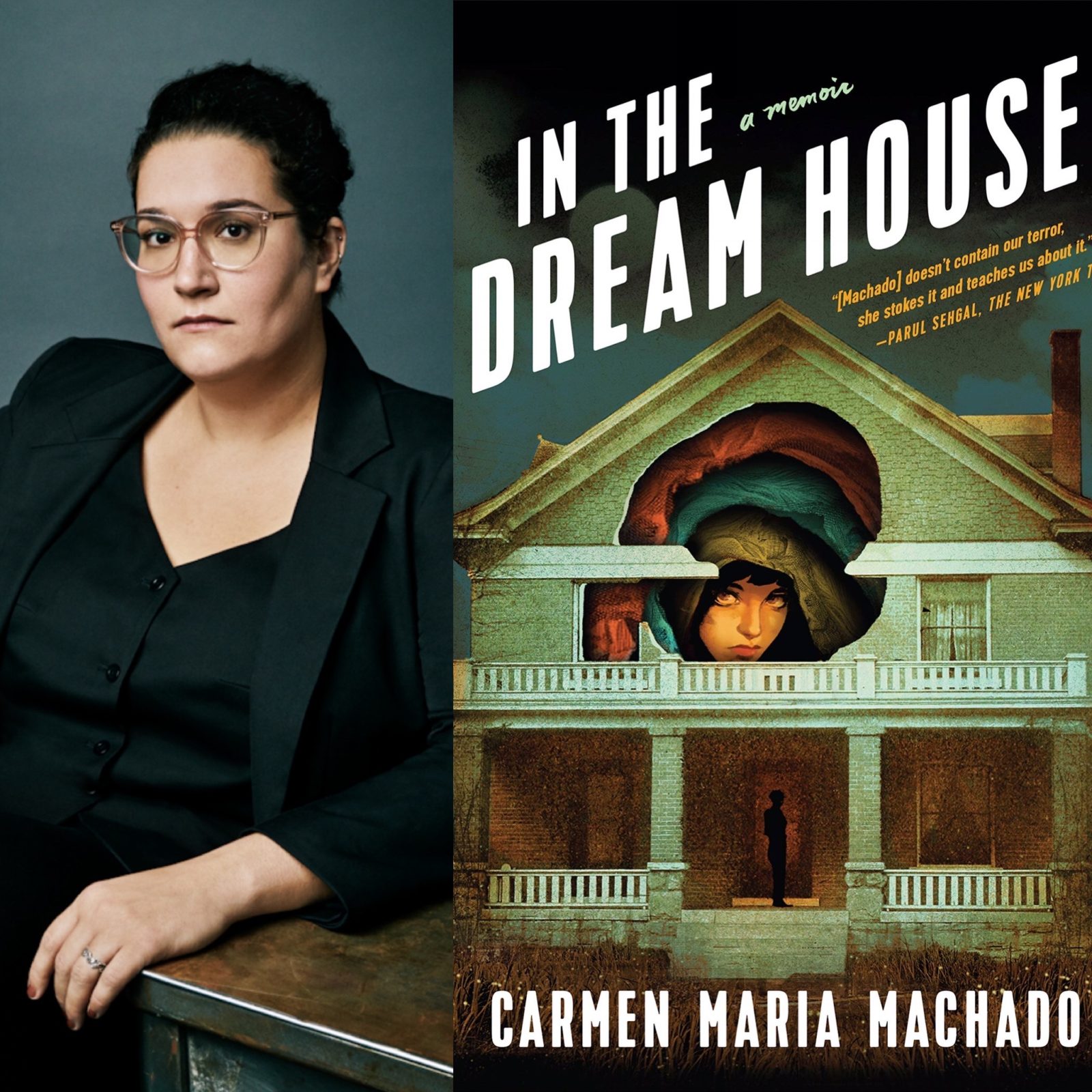

Carmen Maria Machado is the author of the memoir In the Dream House and the short story collection Her Body and Other Parties. She has been a finalist for the National Book Award and the winner of the Bard Fiction Prize, the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, the Brooklyn Public Library Literature Prize, the Shirley Jackson Award, and the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize. In 2018, the New York Times listed Her Body and Other Parties as a member of “The New Vanguard,” one of “15 remarkable books by women that are shaping the way we read and write fiction in the 21st century.”

You can purchase In the Dreamhouse here.

Image Credits: Art Streiber / AUGUST

Carley Moore is an essayist, novelist, and poet. Her debut collection of essays, 16 Pills, was published in May of 2018 by Tinderbox Editions. Her debut novel, The Not Wives, is forthcoming from the Feminist Press in the fall of 2019. In 2017, she published her first poetry chapbook, Portal Poem (Dancing Girl Press) and in 2012, she published a young adult novel, The Stalker Chronicles (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux). She lives in New York City and teaches at NYU and Bard College. Visit her website or follow her on Twitter.