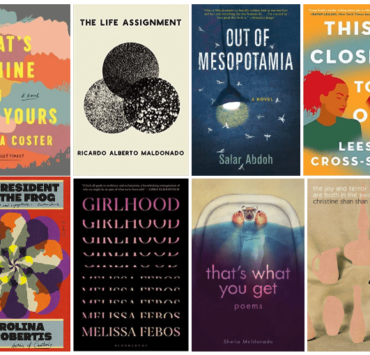

On August 28, 2020, Natalia Sylvester, Elizabeth Acevedo, Jennifer de Leon, and Lilliam Rivera joined me in conversation for a Wordup Community Bookstore Lo’Mas Lit Book Club Event to celebrate their new young adult novels. Natalia Sylvester is a Miami, Central Florida and South Texas raised author who blessed us with her YA debut novel Running. Elizabeth Acevedo is an award studded author of The Poet X, With the Fire on High, and her most recent novel, Clap When You Land. Jennifer de Leon, is an author, editor, speaker, and professor busting out with her debut novel Don’t Ask Me Where I’m From. Lilliam Rivera is an award-winning author and writer of various young adult novels including her most recent, Never Look Back.

Angie Cruz: Natalia, activism is central in your book, Running, so I’d like to ask you, what are the roots to your activism?

Natalia Sylvester: Oh, wow, that’s a great question. I think it’s in those moments, when I was doing research for writing, I went back and I read my old journal entries from when I was 13, 14, 15. I found one entry in which I was questioning all the power dynamics and gender roles in my own household, in my family, all around me. It’s my first rant, it’s my first manifesto of realizing all my frustrations with all of the inequalities around me. I grew up being expected to stay silent. Internalizing this idea that to be a good daughter, to be a good girl you are polite, smile. It didn’t sit right with me. I think a lot about who that silence would serve. I come back to this idea– silence only serves those in power and those who will harm our communities. Even when I am afraid to speak up, that’s where I end up finding the force, the strength and the power. Getting past that fear. I don’t think that fear is something we should all be ashamed of. We need to acknowledge that we have it. This is a scary time we are all in. But it shouldn’t erase our actions, it shouldn’t silence our voices.

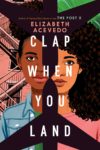

AC: Liz, your characters in Clap When You Land, are going through so much. Who was the more difficult character to write between the two sisters?

Elizabeth Acevedo: I think it’s helpful to know that the story wasn’t supposed to be a dual narrative. It was entirely written from Yahaira’s perspective. I had the entire manuscript done and felt like there’s something missing. And I was talking with Ibi Zoboi, a Haitian writer who wrote American Street, she wrote Pride, and I’m telling her I’m struggling with this character who figures out her father has this whole other family and she looked at me and asked: Why aren’t you writing from the sibling who’s actually on the island? When are we going to hear her? It was this moment of Ohhh… And Camino came through. The voice. Camino took over the manuscript. Yahaira was written first but she did not match up to the momentum I had when I was writing Camino. I had to go back in and figure out her secrets, what are her individual quirks, what are the ways that she moves through the world, I couldn’t see Yahaira as clearly as I could see Camino. I knew how dire her shit was. It was reverse engineering to make the characters hold up their own, through the passages. Yahaira was harder to write because her conflict was quieter.

AC: Ooh, I can see that. When I was reading the novel I did think… ooh she’s having so much more fun writing Camino. I find it harder to write a character that is close to an experience that I know well rather than one that I don’t know as well. The reluctant protagonist is often the one that is closer to us. Right?!

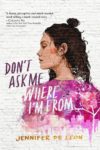

Speaking of how we develop our characters, Jenn, in your book you open the novel with health class. How much did your experience as a teacher inform the novel? Were you also in a program like METCO, that offered students of color scholastic opportunities? And also why do you think that this is an important narrative now for young people to read?

Jennifer de Leon: As a teacher I felt I would constantly give books to my students—my kids—they’d give it the cover and the first page and if they weren’t interested they would drop it. I wasn’t in a program like METCO but I was constantly between worlds. I was hanging out with my family, extended relatives in Boston, then going back to the suburbs with my nuclear family. I lived in a suburb with White friends, White teachers, my White neighbors. So, I felt I was very much in two worlds. When I was 16, I did a program like METCO where I went to Zimbabwe, to do a community service project. I went with all these rich White kids from all over the country. Right now, we are in a time of reckoning. I think we all have to tighten our ponytails, tighten our laces, get in gear to be braver and to use our voice because this is it. Young people feel like, what do I have to say? What can I do? They can do a lot!

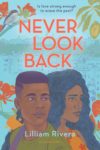

AC: Lilliam, all your books are so different from each other. I love that you have this breadth of speculative and realism across your work. With your most recent novel, you’re retelling a Greek myth. Did you like working within the constraint of retelling a known story?

LR: I grew up watching Black Orpheus when I was a teenager, I love that movie. It is a retelling, set during Carnaval in Rio in Brazil. When I saw it as a kid I was in awe. Then I got into the myth. I was in love with the idea of love and hope and tragedy. I was in despair when I was thinking about writing. Hurricane Maria had touched Puerto Rico and had affected my family. People were lost and people lost things. I was angry and full of rage—still. How can I write this book and find hope? The only way I could do it was using a structure. The myth provided me with a structure and a way to contain my hope, my rage. I wasn’t going to write everything I hate. I needed love. These characters appeared when I needed them. The myth helped me, gave me structure, the house. Then I had to figure out how to interpret their desires and their wants.

AC: And—it’s sexy. It’s sweaty, it’s pre-COVID times, if you miss the summer when people were sweaty on the bus, hugging and touching, this is a good book to read.

LR: It’s true, it’s so New York summer when everyone is half naked, I love it.

AC: All of you have written books with strong characters facing all kinds of challenges. Being that Latinx youth are one of the fastest growing demographics with future voting power. What is your take on youth and the push to get out the vote?

LR: Everyone is pushing on, saying “you got to go vote.” But it’s the young people who are leading this revolution out on the streets. I understand the weight. This is a do or die situation and they are out there, in the face of hostility and violence

NS: I’m glad Lilliam brought up the young people on the streets. When people talk about, Running, they’ll use it to also say ‘Go and vote!’ That’s good! If we have the privilege to vote, we should use it. But my character, Mari is fifteen and she can’t vote. What does she do instead? What do her friends do? When you look through history, at the movement, big changes happened not because lawmakers decided to put new laws into place out of the kindness of their hearts. It was fueled by movements. We can’t wait around for every four years, every two years, every time there is an election and hope they get it right.

People are going to make their voices heard, make it so that they can’t ignore them. My parents couldn’t vote. They weren’t citizens. When people talk about voting being the only power we have, it is a disservice to anyone who isn’t old enough to vote, formerly incarcerated, live in a state that doesn’t give them the right. Anyone, whose votes are disenfranchised, people of color. There are efforts by our own government to suppress votes. Those two things coexist, absolutely this election is crucial.

There are so many things working against us in this system, that I don’t think voting is a form of activism. For someone who has that privilege it’s the one thing we can do. I admire activists who are weighing and risking so much in order to get their voices heard and take real action. Not everybody can be marching, we all have different purposes and skills and passions to lend to the movement. It all matters.

AC: 100 percent— If we look at climate change and the force behind that movement, young people who don’t have the right to vote yet are out there. I think about my own life and how the dramatic differences that impacted me and my community were because of people who went out of their way to help me. Jenn, when you write about education you show the impact when someone takes the time to pull you aside and help you get to the next step. All of these gestures of taking care of each other in our community highly impacted me. I believe your book will inspire or even make young people who have to face their fears and do something scary but necessary feel less alone. Can you share a moment from your past when you stood up for yourself or someone, when and/or faced a fear that you now understand was a crucial turn in your trajectory as a writer?

JDL: It was my freshman year in college, I went to a country club of a college and it was a great opportunity, yada yada. I remember being in a class and there was someone who asked a question about immigration and then boom all eyes on me. 80 eyeballs swooshed. It felt like I was a representative. My face turned red; my neck turned red. That’s the risk, when you do step up, you’re courageous. You turn red, you ugly cry and you do all of those things and it’s okay. But I remember sharing what I had to say. I put it in a book too. Somebody was mad because things were in Spanish. ‘Why when I go to the ATM it asks me if I want instructions in Spanish’? And I was like–Have you ever thought about Florida, Colorado? The Spanish were here first.

AC: Anyone else have a moment you want to share?

EA: I don’t know if this is the best example, but I think I was the one who was comfortable with being vocal in class. I had been part of an organization in Harlem called the Brotherhood-Sister Sol which did a lot for my confidence in terms of who I was and my understanding of history and my push back against Whiteness and White folks who would try to propagate knowledge that was unfounded. So, I remember someone in high school bringing up Columbus. I had to chew them out. The teacher afterwards said: Great job. That was the environment that I was in—it was harder for me to be brave at home. I could defend myself in English, I could get across what I wanted to say, I could wield it. In Spanish I felt a little, tongue-tied. I had to be careful with how I said things, and ask for things and demanded things. Like here’s why I think I should be able to travel abroad with the rest of my high school class.

I wasn’t sure if I was going to be able to go away for college. No one in my family had ever gone away for school. My older brothers hadn’t gone away for school. I tried to convince my mom that it made sense of her youngest and her only girl to go hours and hours away to places she had never seen much less heard of. She could not understand. New York has schools. Your brothers went to BMCC, go to BMCC. But I need to go away. A part of me knew that I couldn’t stay home because I wouldn’t grow into the person I wanted to be. I pushed, stood my ground and explained. I took my mom on college tours with me. That was tough, but I think we imagine that being brave is just outward and in front of audiences. But those little moments of trying to reconcile that you may come from places that make it difficult to be the person you want to be. You can’t abandon those places. How do I bring this woman I adore with me and maybe have her even support me or like cheer me on in this endeavor? Years later, my mom told me there were many times when I pushed back and she thought I made the wrong decision. She said, I’m glad you leaned into what you thought you should do.

I didn’t know at the time if I was right. Jenn, as a teacher, you plant the seed in your students and it doesn’t come back until ten years later. That’s how it feels, these seeds I planted in my mom came back years later. She’ll say, ‘that one time you did that that helped me be brave’. I think that’s super dope.

AC: In Don’t Ask Me Where I Come From, I loved how the mother character does not do the thing I expected her to do. When her daughter was offered an opportunity, it was the mother who was like, No, no—you’re leaving. A lot of the Latina narratives are of parents who resist the departure from the neighborhood or to college.

EA: With YA people ask what’s one of the things you get in emails that bolster you? It really is the interactions I have with moms who tell me they read The Poet X and it how changed how they mothered. Or they told me they bought the book, and this will be women who are 35 or 40, I bought the book for my mom, so that we could talk about something that happened when I was 15. These are now touchstones; our books allow for conversation. I remember buying Julia Alvarez’s In the Name of Salomé in Spanish so my mom could read and in English for myself so that we could discuss it. Reading those bilingual books was huge. I wanted a thing we could share. Our books are that. They change the child but also the parent, too.

AC: In Natalia’s book too, the parents defy the stereotype we see in movies and in our lives.

NS: Mari’s mom was not someone I spent a whole lot of time writing in the initial draft. The point of the book is her dad is running for president. But I realized so many things that were happening occurred across generations. Mari’s mom participated in Mari’s own silencing. I love what you said Liz, it’s true. By the time I finished revising, I realized Mari’s journey is one that ends up empowering her mom as it empowers her. There is something beautiful about the ways we witness each other’s journeys. I don’t think that there is an age limit on how much we help each other change and evolve, let go, not let go of regrets. But we realize we can let go of things we thought were being imposed on us. Take this pressure of staying home. I went away to college for one semester. I was the first in my family to do it and then I came back to Miami because that was my journey. Later on, my sister who is older than me told me, ‘I really look up to you for that I didn’t realize like I could’ve done that too’.

The dynamics flip. You don’t have to be older than someone to teach them or to have an impact on them. We are all learning so much even today. Lilliam, like what you’re saying, so many young people are the ones that are out there right now. It’s sad that’s what it is right now. The adults in power should be out there too.

LR: I have spoken about my brother who was awarded a scholarship to attend a boarding high school away from home. We didn’t speak to him for four years and we didn’t realize how devastating it was to his psyche. He was coming from the housing projects, he didn’t have money, couldn’t call and ask ‘Hey can you send me money’? He was around people who all had money. I didn’t know how devastating that was until he graduated. He got into Cornell and then he became involved in the radical movement, he became outspoken. Those were four years of silence. I think about myself too. There was no complaining, we just took the opportunity. I have a 15-year-old and I push. I’m like, we’re getting the best for you. But sometimes it’s not the best. The push is to educate people to find their truth in all this.

JDL: There’s that great quote that Leslie Marmon Silko has about stories having the power to heal, to create. Stories are everything. Maybe young people, older people, like you’re saying Liz, leave seeds that might sprout next week, next year, ten years from now. They might ignite a conversation that might otherwise not have happened, what did Walter D. Myers called it, that shock of recognition when you read someone like yourself in a book. It doesn’t have to be that they’re like you on a level of identity but that you recognize yourself on that page.

AC: What were the books for you as teens that either got you to writing or that you recognized yourself in a profound way?

EA: Julia Alvarez’s Before We Were Free was one of the first Latinx texts I ever saw in my middle school. And as someone who grew up hearing many fairy tales it was incredible to think about this character who was like, ‘Oh my mom has been telling me stories about growing up under Trujillo forever and the witches who would sit on people’s houses and listen in. That’s how they would find out who was spreading secrets about him or talking’.

But I do want to loop back this question of becoming. It’s complicated. Often when we talk about representation, we look at other people to tell us and prescribe for us how we get there. How do I become you? What we really want to become is the thing—how do I do the thing you do as myself? It’s curious to want someone to give you a blueprint. I hope folks are creating their own definitions of what it means to have become the thing they want to be. My definition of becoming is to feel free in how I live in my language. Once I stop feeling apologetic for every thought I had and how I expressed that thought, was that too hood? Was that too proper? Yo, my vocabulary is expansive and sometimes people are like, well how do we grab the voice? Nah, there’s no grabbing this is who I am. It’s in poetry, fiction when I get up on stage, when I am in my house and now working. When I am talking to my family. How can I be my most free self at all times? When I look at women on stages who are greatly admired, I believe they have found that core in themselves regardless of what they’re doing or how they speak or whatever institutions they’ve gone to. I love Cardi because she gives herself at all times and she has mastered what it means to be herself. Without anyone else telling her how to be bearable. I want to become that. I want to push at how we look and how we keep imagining. Becoming is not static. I became someone who is published and I became someone who is now writing a screenplay and I will become many other things. I may become a rapper like Cardi.

AC: Please do.

EA: I’ve got bars, yo, I’ve got bars. I wish someone had told me when I was 15 and desperately looking at folks asking, who do I, who can I be, who looks like, who I imagine. In wanting to latch onto people I wish I had been told, ‘Yo, there’s no blueprint. You’re going to have to make it up and it’s going to have to be unique to you.’ That becoming is going to be whatever vision you are projecting. I think folks who rupture with me have gained a lot of success. I’m still not comfortable because maybe they still haven’t answered the original question. What did you want to become and who did you want to become before you look sideways at what other people were doing?

AC: Yeah, snaps.

LR: Those are the bars right there.

EA: Where’s my beat, where’s my beat. That’s the intro to the album.

AC: Does anyone else here have a transformative book to share?

NS: The first books I saw myself in weren’t me seeing myself as a Latina. I didn’t read Latinx authors until in high school. I moved here when I was four. I started school not speaking English, it was hard for me to learn to read. Once I learned English I was no longer in ESL. But I didn’t yet have a full grasp of the language. Back then, they didn’t know you should teach someone to read first in their native language.

My teachers would put me in the back of the class and send me home with cassette tapes and workbooks. The book that clicked for me was Matilda by Roald Dahl. Matilda is a little girl who reads all of the books in the library. At the time I had had surgery on my hip. I was not at school for six months at a time because. I had a cast from my chest to half of my left ankle and half of my right foot. I would go to work with my mom. My mom would take me in my cast and wheelchair and I would read. It was wonderful to know this girl whose superpower is reading. Look at all these places she’s going. Through books, through imagination. When she wrote limericks on the first day of school, I wrote limericks. My mother had a typewriter in her office and I wrote limericks. It was the first time I felt empowered, in a moment when I didn’t feel empowered in the world around me, my physical place. I carry that, I look back, I think God, that was such a fun time in my life. I loved those days in my mom’s office reading and typing with her. It’s a beautiful testament to what stories can do.

EA: I want a book of a girl who homeschools herself. That is so badass. I gave myself my own curriculum and homework and was out here. That’s amazing, I was so moved.

LR: I’m sure that’s happening now with this pandemic.

EA: I know, oh word, word, yeah.

Elizabeth Acevedo is the New York Times-bestselling author of The Poet X, which won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, the Michael L. Printz Award, the Pura Belpré Award, the Carnegie medal, the Boston Globe–Horn Book Award, and the Walter Award. She is also the author of With the Fire on High—which was named a best book of the year by the New York Public Library, NPR, Publishers Weekly, and School Library Journal—and Clap When You Land, which was a Boston Globe–Horn Book Honor book and a Kirkus finalist.

Clap When You Land is available for purchase here.

Jennifer De Leon is the author of Don’t Ask Me Where I’m From (Atheneum/Simon & Schuster 2020) and the editor of Wise Latinas (University of Nebraska Press). An Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Framingham State University, and a GrubStreet instructor and board member, she has published prose in over a dozen literary journals, including Ploughshares, Iowa Review, and Michigan Quarterly Review. She lives in the Boston area.

Don’t Ask Me Where I’m From is available for purchase here.

Lilliam Rivera is an award-winning writer and author of the young adult novels Dealing in Dreams and The Education of Margot Sanchez both by Simon & Schuster and available now in bookstores everywhere. Named a “2017 Face to Watch” by the Los Angeles Times, Lilliam’s work has appeared in New York Times, Elle, and Los Angeles Times, to name a few. She lives in Los Angeles.

Never Look Back is available for purchase here.

Natalia Sylvester was born in Lima Peru and came to the U.S. at age four and grew up in Florida and the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. She received a BA in Creative Writing from the University of Miami and now works as a freelance writer in Texas. Natalia’s first novel, Chasing the Sun, was named the Best Debut Book of 2014 by Latinidad. Her latest novel, Everyone Knows You Go Home, won an International Latino Book Award, the 2018 Jesse H. Jones Award for Best Work of Fiction from the Texas Institute of Letters, and was named a Best Book of 2018 by Real Simple magazine. Natalia’s debut YA novel, Running is out now from Clarion Books/HMH.

Running is available for purchase here.

Watch the entire Word Up – Lo’Mas Lit Book Club event with our featured authors here:

Angie Cruz's novel, DOMINICANA is the inaugural bookpick for GMA book club, and the Wordup Uptown Reads selection for 2019. It was also longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie award in excellence in fiction for 2019. It was named most anticipated/ best book in 2019 by Time, Newsweek, People, Oprah Magazine, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Esquire. Cruz is the author of two other novels, Soledad and Let It Rain Coffee. She's the founder and Editor-in-chief of the award winning literary journal, Aster(ix)and an Associate professor at University of Pittsburgh where she teaches in the MFA program. She splits her time between Pittsburgh, New York, and Turin.