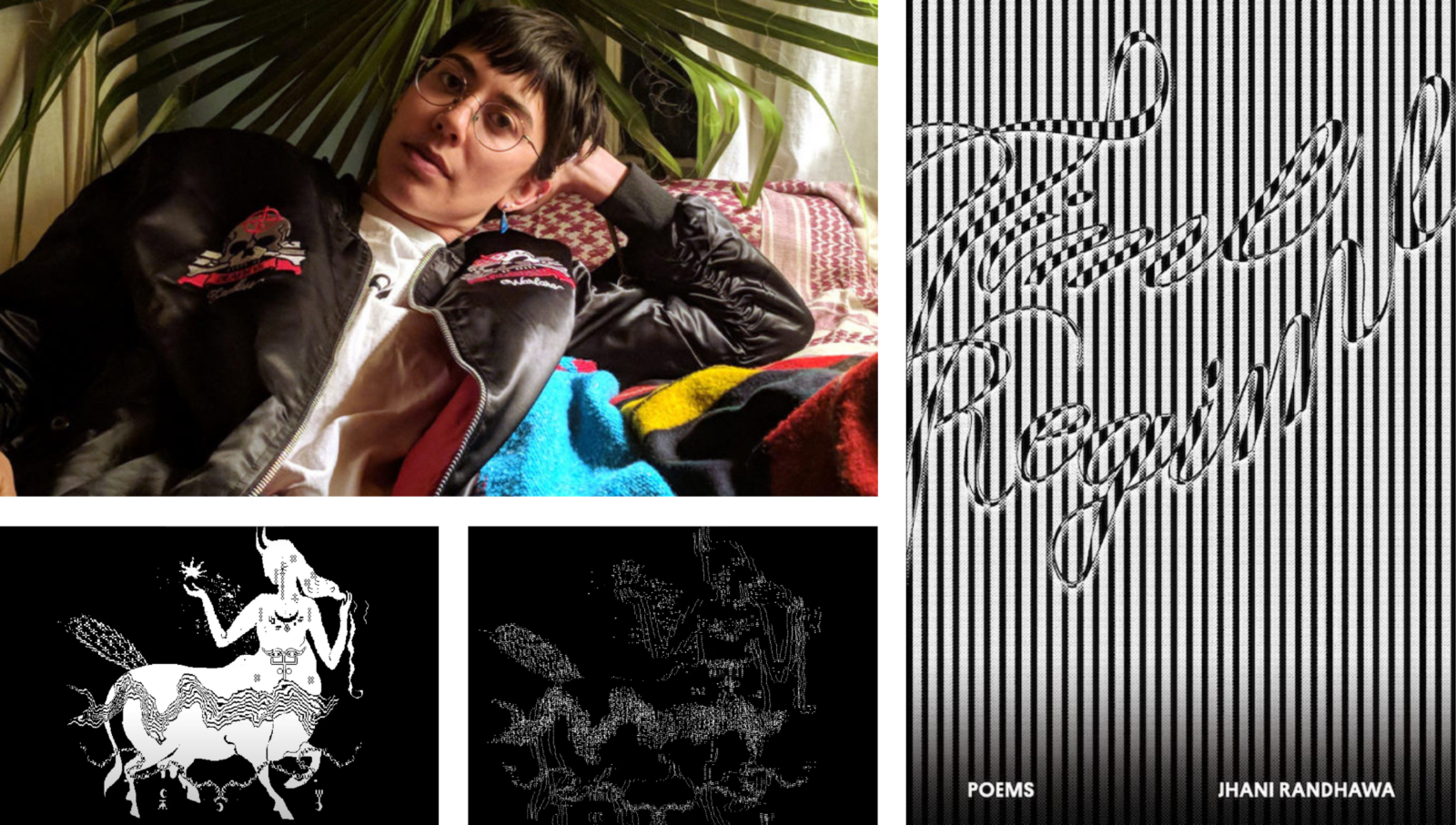

Kenyan-Punjabi, Anglo-American poet Jhani Randhawa’s debut collection, Time Regime, was released on April 1, 2022 (available here on bookshop.org and elsewhere), out with Gaudy Boy, a publication project by Singapore Unbound.

Randhawa won the 2021 Gaudy Boy Poetry Book Prize; judge Dororthy Wang wrote, “Spectrally luminous. Randhawa’s poetry is completely its own . . . [with] a foot both in the human ravaged world and in the geography of the poetic imagination.” Aster(ix) Journal Managing Editor Amanda Tien spoke with Randhawa about eco-poetics, the relationship between story and poetry, and collaborating with visual artists.

Amanda Tien (AJT): Throughout the collection, you bring in the natural world. I’m fairly new to the world of eco-poetics; I think it’s very much an art form of our moment, our generations so consumed with climate matters. I was particularly fond of “Scriation II: Recrystalize” and this section on lilacs:

Did you know, lilac has not been in New York long enough to form an evolutionary relationship with insects that would, in turn, be eaten by birds? “Lilacs are beautiful,” botanist Mariellé Anzelone admits, “but they’re like styrofoam. You find these things in the landscape that look and smell like plants to us. But for animals around them, they don’t act like plants. They might as well be statues.”

The metabolic evolution of flora in New York has stopped, in the case of lilac.

The landscape is mausoleum. What do you do with this?

from “Scriation II: Recrystalize” by Jhani Randhawa

How do you see the relationship between your writing and the natural world, between words and our planet?

Jhani Randhawa (JFK): Poetry, language, feels like a practice—a study—of relation. For me, ecology is the root of all relation. The blossoming of new language experiments in relation, or of lenses (eco-poetics is a lens) to discern these experiments, are ever emergent; but perhaps they take on urgency under pressure. We sit, we cook, we make love, we yearn, we isolate, we gather, we read deeply, we get the cops called on us, we labor, we vanish, we buy shit, we meditate, we give nicknames, we brutalize, we sleep at the precipice of climate collapse. The planet communicates, though not in words—and we exist in this urgency, this tension.

Literacy is weaponized so often as a means of consolidating power and belonging, making the experience of belonging and connection scarce. Words are used to guide traditions of relating to the planet, and while the planet cannot express in bureaucratic language, the post/neocolonial tradition is to consider the planet an inert inconvenience. Words are tools that can erase the traces of symbiotic codependent relationships among humans, let alone between human and more-than-human beings.

Central to my writing, especially in Time Regime, is the dissonant (though not always displeasurable) experience of experimenting with centering ecological inter-being, yearning for and grieving the paradox of a radically shared-self and the aging, ill, diasporic body ravaged by and complicit in the machinations of an increasingly toxic condition in late-capital. I’m interested in how my practice, my writing, becomes (and invites) devotional, an offering of collective grieving, as an antidote to extraction, scarcity, and the shame of separation.

THE PLOT IN POETICS

AJT: I primarily write fiction, and so I was excited in various moments in Time Regime where I felt the rumblings of capital p Plot. There are lines where it is clear there is a greater narrative occurring and happening in the work, especially as you play with prose poetry. For example, this tension between land mass and intimacy:

But it is also, eros, the collapse. As I climb, testing boulder’s mettle against ankles’

from “Meanwhile, Acts of Human and Nonhuman Animal Cruelty” by Jhani Randhawa

mettle, I crest, surprised—who I was before the boulder suddenly curved down is

different than who I am, straddling the apex. It feels immeasurable. And just there,

from this elevated angle, I can catch a corner of your bare shoulder nestled in blue

shade. Blue vibrating.

And then, later in the collection:

I have witnessed signs of extraction settling in the vale

and have pieced together what remains of my hyperbolic

decay. Our molecules are speeding up. I cannot find you.I cry out for amnesia, to yield to the shadow of the volcano.

from “VI. I Believe” by Jhani Randhawa

This is your debut collection. Tell me about what that process was like for you, considering connecting ideas, plot, stories, images across a book.

JFK: What a wonderful question—as a maker with very little training in literary craft, this question intimidates me, and I want to think more about this! In arranging this body (of work), ideas of (inter)dimensionality, porousness, rhythm, digestion, erosion, pace, negative space, frenetics, the resonance between a speaker’s and a reader’s somatic experience, the collisions or moldings of literal set-pieces or theoretical architectures were important to me. Negative space and logorrhea feel key here. What does a process of attuning to negative space mean, what does it feel like? I’m interested in dreams, in channeling, in slow accretion, in residues surfaced by the intergenerational, migratory, flooded body. How the negative space in billions of cells somehow creates a lifeform.

AJT: Your work asks many questions, sometimes literally. In the titular poem, you write, “What is the gender of leisure, of music? What is the performance of time?” How do questions inform and guide your work? What surprises you?

JFK: Unlearning, not only to undo but to make space, is one of the most challenging practices I’m committed to. In order to make space, and in the space that is reconstituted, left raw, first I sit’ then I ask questions. I’m trying to learn how to ask new questions of experience on earth with others, to cultivate curiosity, to dislodge and trouble inert preconceptions. Questions, and the conversations they stir, are disruptive tools for transition, transformation, solidarity, witness. The frequency and volume of insect sounds surprise me (also frogs in the desert).

ARTIST & ACTIVIST

AJT: I loved the book trailer made with Somnath Bhatt. Tell me about that collaboration.

JFK: So aglow that the trailer spoke to you. I’m maybe sometimes too earnest and severe about co-conspiring; and I sincerely adore the challenging practice of collaborating. Time Regime is built of impressions, porosities, inconclusive and myriad threads and that, I hope, create generative opportunities for threads to be picked up by other makers. Poetries are moving relational fields—agitations—and can be methods of attuning to our multiple selves, to others, to systems that entangle human and nonhuman subjects. Moreover, poetics can be—as Fred Moten expressed in a workshop in 2020 while referencing the Combahee River Collective—a means of “sharing better.” I’m trying to be in a practice of sharing better. Hence, Somnath Bhatt (and later, Thea Mesirow).

Som is an amazing and visionary artist, and a generous collaborator, and I’m honored they felt connected to this work. When I reached out to Som, I shared a bit about the book, who then invited me to explore some core images or themes to develop an initial drawing from. What came to mind first was a beautiful, seemingly pixel-molting digital animation of a running bull on Som’s website; then a sensation of drift; then bodies of rice germ, red ticks, a grandmother’s labor-worn hands and skin cells, limestone deposits, boulders, ice caverns melting into rivers of milk, machine intelligence, shaggy language, the mythological winged cow Surabhi who sometimes appears with a peacock’s tail (whose image appears across, and is arguably shared by, Sikh, Hindu, and Islam). Som then produced a beautiful still image, placing Surabhi in communication with my note that the works in Time Regime “assemble an emergent mutant body that ingests, metabolizes, applies and interrupts ‘trashed’ and repurposed objects, the psychic crud of neocolonial and technofascist wage labor, reticence, and the divine.

With these materials in its guts, the mutant body seeks to interrupt neoliberal imperialism’s rhythms and expectations; the body seeks communion with mess.” The animation came next, with Som’s invitation-as-imagination that I would read a poem over the animation, which made me very nervous. Thea Mesirow, an amazing cellist, was available to compose and perform a 30-second piece to weave into Som’s animation. Thea used the open C and its fifth partial to explore the variation within a single musical interval, mirroring the five sections of the collection. Only after feeling so marvelously haunted by the layered cello, aligned with Surabhi’s (de)construction, did I feel courageous enough to record an excerpt, intuitively chosen, of the poem “Cura eats, and lover, Blue.”

AJT: I feel very lucky to be entering the literary space at a time when there is a legacy of great BIPOC writers as well as contemporary leaders. I’ve seen and read more Asian American writers in the last five years than I had in my entire life prior. I mean, even your publisher, Gaudy Boy, exists to publish Asian and Asian American voices and was made by Singapore Unbound in 2018. What is on your mind, as this community evolves?

JFK: At the Asian American Caucus, co-hosted by Kaya Press, Kundiman, Asian American Writers Workshop, Asian American Literary Review, and the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, at the AWP Conference in Philadelphia just a few days ago, community members raised questions of what Black and south Asian solidarity movements could look like across diasporas, given the effects of class mobility, caste privilege, and state complicity. On my mind is the urgency of critical reckonings between queer experience, caste, class, and indigenous and racial solidarity movements in the Asian American and Asian-diasporic-in America experience, and taking anti-Black racism in our communities to task. There are historical examples of Black and Asian solidarity movements—that are not without their shortcomings—but they have been long and strategically ignored (too much revolutionary potential, and so much damage done). Caste disenfranchised communities have traditionally collaborated with Black civil rights and liberation movements to a greater degree than caste privileged groups have, and I’m interested in our communities deeply considering the shapes of internalized white supremacy, as well as our complicities in state-sanctioned, racially-motivated harm.

SHARE BETTER

AJT: Your bio identifies you as a “Kenyan-Punjabi/Anglo-American” artist and scholar. I would love to hear your reflection on what it means to bring those identities and backgrounds into this space, and into your work. Please share whatever you are comfortable with, or that you would want other people to know and understand.

JFK: I mentioned earlier “sharing better”—what I didn’t explicitly share was that a practice of sharing is in service to models of reparations, abundance, listening, courageous vulnerability. Sharing is in service to disrupting models of scarcity, erasure, transactional relationships, and capitalist possession. I mention all this because all those conditions exist in my mixed heritage. It is important to me to complicate homogenous narratives of identity, and to lift up the frictions, disenfranchisements, and privileges that mark but cannot wholly define my hyphenated identity. I’m interested, I think, in placing these backgrounds into art’s experimental and interstitial space and engaging deeply with what happens there; and maybe, I’m curious about how study (or scholarship) can itself be an art practice.

It is important to me to lift up my Kenyan-Punjabi roots for an American audience who, for the most part are not taught that the British Empire’s colonization of India and East Africa overlapped in material functionality, in timelines; or that folks living in south and southeast Asia elected or were coerced into indentured labor for empire during and in the aftermath of chattel slavery; or that before European colonization, a millennia-long history of human circular migration and cultural weaving between central Asia, south and southeast Asia, and Africa was practiced. Bringing these national/ethnic forms of identity into the space means a kind of strategic (il)legibility in identity-and-representation driven community formations. But bringing these parts of my life into view is also a standpoint offering at some kind of center; hopefully, by doing so, I can in good faith recognize someone else’s center, make space. Share better.

Jhani Randhawa is a Kenyan-Punjabi/Anglo-American multidisciplinary artist and independent scholar. They received a B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College, and live between the U.S. and the U.K. With Teo Rivera-Dundas, Jhani is a co-founding editor of rivulet, an experimental journal dedicated to investigations of the interstitial.

Amanda Tien is a writer, artist, and marketing strategist, currently working on her first novel while pursuing an MFA in Fiction at the University of Pittsburgh. Her work has been published in Salt Hill Journal, Public Books, Poets.org, Call Me [Brackets], Columbia College Today, and The Punished Backlog. She is the 2021-2023 Managing Editor for transnational feminist literary journal Aster(ix). She holds a BA from Columbia University where she co-founded Culinarian, a magazine connecting student life to the world of food and drink in New York City. Her work can be viewed at www.amandatien.com