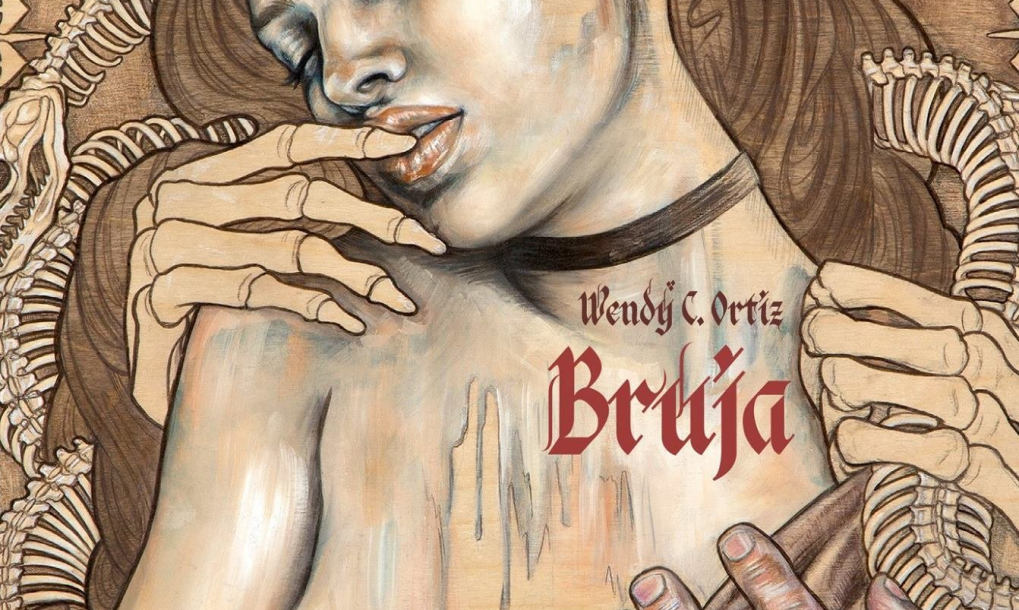

Born and raised in Los Angeles, where she now lives again, Wendy C. Ortiz is the author of three works of nonfiction: Excavation, the unflinching account of a dangerous relationship between a young girl and her older teacher; Hollywood Notebook, a collection of fragments and meditations on the author’s West Coast life and relationships; and her latest, Bruja, a “dreamoir” in which the characters and events of the previous two books resurface through the image-rich filter of the subconscious mind. Wendy is also a family and marriage therapist and the mother to a young daughter.

Arielle Greenberg: First, a most important question: Am I gleaning correctly from things you say in Hollywood Notebook that you and I are astrological mirrors? My sun is in Scorpio, moon in Taurus.

Wendy C. Ortiz: YES! Wow, wow, wow. Of course we are!

AG: How does your astrological chart explain you to yourself? What does your zodiac say about who you are?

WCO: For a time, after I first had my chart done, I began reading more deeply into astrology texts, then started gathering the charts of people I knew and keeping a notebook on what I found. I also thought I would become an apprentice to an astrologer. I still want to do that.

When I think of my own astrological chart, the element that stands out to me is how I’m embodying my rising sign, Sagittarius, more and more. My Scorpio moon is all the emotional intensity I’ve been carrying around inside since the beginning. My solar foundation as a Taurus shows up in how people experience me as a grounding force, persistent, sometimes stubborn, but typically solid. My Sag rising, especially at this point in my life, really does feel like the embodiment of horse energy, arrows, showing up big and bold.

Have you seen my Celestial Body Language prose poem at Poor Claudia? I tried to explain elements of my chart there. And I found I could not read the part I wrote about Sagittarius rising in public because it would start to make me sob, because it encapsulates the very real fear of what I want for myself. I’m not quite all the way there in embodiment yet.

AG: But you have it! It’s there in your rising sign!

WCO: I’ve only really felt the power of that sign in my chart since turning 40. My 40s have been a revolution; I am not being hyperbolic. Some internal shift I couldn’t have imagined has occurred and I’m still riding it.

In my 20s and 30s I was dealing with other more complicated elements of my chart—like Mars in Pisces. That’s my least favorite element of my chart: the heat and power and will of Mars but filtered through the sign of the fish. A little warrior fish that prefers to hide among the rocks. The water-and-fire mix make for complications.

AG: I’m sure we could talk astrology all day, but let’s move on to your writing. One thing I often say to students in creative workshop classes is that there are some very significant, powerful human experiences that rarely show up in literature, and it’s our job as writers trying to forge a distinctive path to identify those and write them down. An example I often give is what it feels like to be part of the audience at a summer music festival: that orgasmic, cosmic, communal feeling of sharing this particular pleasure with a crowd of strangers. And you write about it, really in all three books! I was so excited to see that.

WCO: No one has ever pinpointed that in my work! I appreciate that you see that. I feel like I’m always trying to grasp at how to write this well and completely.

AG: It’s such a primal human experience, for those of us who have had it and cherish it. It’s hard to articulate. In my opinion, there is no other experience that directly replicates it. Because in what other context do we feel that kind of tribal bond with a mass of strangers?

WCO: I feel like I could try and write the experience of hearing Trent Reznor sing “Hurt” with thousands of people as a chorus, my voice included, for the rest of my life and never get it quite right.

AG: After reading your three books, I’m thinking about them as “unprocessed” vs. “processed” literature. I’m talking about the end product, the published book, here. Excavation is highly processed, at both the craft and psychological level: it is a work about processing trauma, memory, story. Hollywood Notebook feels unprocessed: it’s a notebook, the raw material itself. It’s an anti-narrative, whereas Excavation works hard to make a clear narrative. Bruja is somewhere in between: a crafted transcript of the raw stuff of dreams.

WCO: Yes. Excavation had the benefit of going through fourteen years of drafts and feedback. Hollywood Notebook began as a blog—before we used the word blog for this kind of writing—and when the website came down, I had captured that text knowing I would do something with it. The editing of it was much lighter than Excavation. And Bruja, which began as a blog I was keeping at around the same time as the blog that became Hollywood Notebook, had to have its own kind of editing to make it hang the way I wanted it.

AG: So the books came about differently, through the editing and revision process, but part of that difference is also about structure, right? Now that I am teaching creative nonfiction, structure seems to be the thing students struggle with the most. When in the process do you land on a structure? How much structuring work went into each book?

WCO: How I land on a structure has changed over the years. With Excavation, I struggled to find the structure. I experimented with different structures, hated them. It wasn’t until I hit on the idea of writing chapters that tell the reader what the young adult me was up to that things clicked. Those chapters provide another dimension the book needed, even required.

With Hollywood Notebook, I wanted to keep the journal-like structure intact as much as possible. When we were editing it, my publisher noted the lack of an arc, and asked if I would add a few short chapters that would expand the very limited arc, and that was an interesting exercise: to keep the structure intact, to go into my head in the past and write something as though it had been written then, and have it seamlessly slide into the text as a whole.

As a “dreamoir,” Bruja also had its own inherent structure, that of a dream journal: my concern was mostly in how to present these seemingly random narrative bursts in a cohesive way while staying true to the order in which they arrived. Also, I approached Bruja as flash pieces, which helped the sense of cohesion, at least from my standpoint.

For Bruja, I wanted to look at the narrative as a maze, with light posts indicating twists and turns. Readers of Excavation, Hollywood Notebook, and my essays will see the names (pseudonyms in most cases) of characters they’re familiar with in Bruja. But if someone who hasn’t read those books approaches Bruja, my hope is that they’ll see a loose cohesion and enjoy the maze.

AG: I was just going to ask about this, about how the first two books function like a key to the third. I found that satisfying, reading all three books together.

You call Bruja flash pieces, and the short form is very hot right now in creative nonfiction, with writers like Claudia Rankine and Maggie Nelson producing such significant work in this form. What’s your relationship to the short or flash essay?

WCO: It’s a form I feel naturally suited for, mainly because I feel the intense relationship the short or flash essay has with poetry. I want to get all mixed up in the relationship between poetry and short essays. I love that place.

AG: That’s perhaps your Scorpio moon coming out.

WCO: Ha, yes. My Scorpio moon is sooo present in my writing.

AG: I also talk a lot with my students about consistency, about limiting one’s aesthetic palette and teaching one’s reader to read the work by making the aesthetic parameters really clear. But I know not everyone values this the same way that I do. Inconsistency is challenging to my Virgo rising tendencies! How do you feel about consistency in a literary work? I was struck by the “hello, first boyfriend” section in Excavation and the Bush transcript in Hollywood Notebook, how they are unlike anything else in either work.

WCO: I’m very aware of all the voices I carry inside me and how they constitute an amalgamation when it comes to “voice.” I understand about my work that different voices will show up and I allow them to. I also understand that, commercially speaking, many readers, when they find a writer they love, can’t wait to read the next book and are consciously or unconsciously hoping for the same voice. I don’t do that. I can’t. In fact I’m very nervous when people say, “I loved Excavation! I can’t wait to read your other books!” Because I’m like, Ohhh…you may hate my other books, then. They are nothing alike. The voices are all so different. My palette is huge and I like to get messy with it, and it’s a palette that may in fact be growing.

The Bush transcript in Hollywood Notebook was the piece that most disrupted people’s reading of Hollywood Notebook, based on feedback I’ve heard and read. It was pointed out in a review of Hollywood Notebook as perhaps not being necessary but every time I look at it, I know it was necessary.

A poet I admire and respect greatly had written on my Facebook wall when reading Excavation that she loved the “hello, first boyfriend” section, and that indicated to me that I had hit my mark. Yes, the voice veers off. That veering off reflects what is really going on in the interior. And yet I could not sustain a whole narrative in that voice. It just pops up, and I let it.

AG: One of the things I found most moving about the story in Excavation is the desperation we all feel—or the desire, really—to be seen the way we want to be seen. To be in relationship with someone who sees us for the self we most want to project in the world.

WCO: Yes, it’s a lifelong desire—for me, anyway.

AG: I have a theory that it’s at the core of all relationships, really. It just doesn’t always happen, or isn’t always healthy the way it works in reality.

WCO: –which gives it the desperation feeling. I was actually just talking about this with a witch yesterday…

AG: You write, very movingly, about how you did not have the impulse to do to your own students what your teacher Jeff did to you. It just wasn’t in you. That resonated for me: my mother did things as a parent that I worried I’d do as a mother, but once I had my kids, I realized I couldn’t parent that way if I tried. Why do you think it is that some of us have it in us to not repeat our own traumas on others, while others seem fated to do just that?

WCO: The awareness that certain traumas had not been repeated in my own family reminds me that I am not bound to repeat. I have the power to make a different choice. My grandmother was physically and emotionally abused by her mother, to the point where even as an elder, my grandmother had nightmares about her own mother that she shared with me when I was a child. When she raised her own daughter—my mother—she was emotionally abusive but scaled back, if that can be said, on the physical abuse. My mother has told me about being slapped by her mother in certain circumstances, which is a far cry from the abuse my grandmother sustained. My mother, for her part, modified her own behavior as well—she never hit me. She did not perpetuate the abuse. This is one piece of a much bigger picture, of course, because I was harmed in my own upbringing by my parents’ alcoholism and its effects, but in this, at least, a cycle was broken. It reminds me I can continue breaking cycles.

My partner and I talk about how, even in the smallest ways, the most minute modifications of our behaviors as parents, we are LIGHT YEARS better parents than our own were to us.

AG: But I also find it interesting about intentional “scaling back” versus simply really seeming to not have any impetus or impulse to go anywhere near that territory. You didn’t have to talk yourself down from seducing your students—you could never even imagine doing so. It was the farthest thing from your mind.

WCO: Yeah—it was definitely the farthest thing from my mind. There is nothing attractive or seductive to me about misusing power in the classroom with students that young.

AG: Let’s focus on the newest book a bit. The level of detail you relay in the dreams in Bruja is impressive and fascinating. Do you think you’re a skilled dreamer, or a skilled rememberer of dreams?

WCO: I used to be a skilled rememberer and recorder of dreams. It might follow that if I was a consistent recorder of dreams that made me skilled dreamer. My dream life now is so very different than it was; I don’t think of my current self as a skilled dreamer or rememberer.

AG: How long ago were the dreams in Bruja written down?

WCO: Roughly 2002-2006, I think. I deleted the years from the manuscript. I can only guess at the exact years now based on what was happening in the dreams, who shows up, what threads keep asserting themselves.

AG: What do you see as some of the overarching threads, the narrative themes of Bruja? I see a woman who wants her parents to know she’s intact. There are obviously a lot of animals—

WCO: Secrets come up a lot; my issues with monogamy are reflected back from Hollywood Notebook; a sense of overwhelm and grief I didn’t know how to deal with. Loss is a constant subject, sex, death, and yes, my parents come up a lot. Particularly my mother, who I think of as the most complicated relationship of my life.

AG: Bruja is obviously an unusual kind of book, a “dreamoir.” How do you imagine or want it to be used?

WCO: I’m totally aware that there are people in the world who HATE hearing other people’s dreams. This book is not for them, unless they’re willing to look at it as flash pieces that come together to form a jagged narrative. I like to imagine that this book is for people who love dreams and dream-life, and look at dreams as an alternate reality lived each night. Bruja is a memoir of my subconscious during a particular moment in time. I personally would love to read more memoirs of the subconscious. Dreamoir or dream journals: I want them.

I did keep one very important dream out of Bruja, even though I had considered it the opener at one point. It was a dream I had about a week—two weeks?—before 9/11, with imagery very connected to the events of that day. I told my coworkers about the dream when it happened. I was about to leave Olympia, my home of 8 years, to move back to L.A., and we all saw the trauma of the dream as being connected to what was happening in my life. But when 9/11 happened, I understood that it was suddenly taboo to talk about what had happened in my dream, the weird images that felt familiar to what I was seeing on TV screens everywhere. My coworkers remembered my dream, and I was told in somewhat unspoken terms that it was not to be discussed again.

AG: Because they thought you really were a bruja, psychic, and it scared them?

WCO: Maybe. I think it was too scary and painful to approach. Sometimes even for me.

AG: All three books chart a simultaneous impulse toward self-destruction and self-preservation. I don’t want to call your speaker (or you) a survivor: I like the term “thriving” better than “surviving,” because it’s more empowered, more of an intentional choice. She is/you are a thriver. What would you say is your current relationship to self-destruction vs. thriving?

WCO: One of the ways I understand myself through my astrological chart is this very thing: the impulses I have for self-destruction vs. thriving. I feel like it’s similar to my nature with regard to how I feel, at core, feral, but have also strived for a certain amount of domesticity. I have to constantly be aware of my capacity for self-destruction. In some cases this means feeding it a little, like a homeopathic, and in other cases it means staying far away from that which I know will destroy me. My will to live, to thrive, is also very strong, equally if not more so—it fluctuates, probably. And I’d have to say, now, that the fact that I have a kid who I’d like to have grow up with an intact parent also keeps me from self-destruction.

Buy the book!

Arielle Greenberg’s newest books are the poetry collection Slice and the creative nonfiction work Locally Made Panties. She is co-author, with Rachel Zucker, of Home/Birth: A Poemic, and co-editor of three anthologies, including the forthcoming Electric Gurlesque, co-edited with Becca Klaver. Arielle writes a column on contemporary poetics for the American Poetry Review, edits the series (K)ink: Writing While Deviant for The Rumpus, and lives in Maine. She teaches in the community and in Oregon State University-Cascades’ MFA.