In the summer that my neighbor’s husband got stopped and sent to Rikers, I rode with her on visiting days, since she hated going that trip alone. We made a ladies’ day of it twice a month, whenever his last name fell on Saturday, catching two trains out to Queens Plaza and stopping for green chilaquiles and runny fried eggs before catching the 100-Limited through Ditmars and over that long bridge out to the island.

A few times, I noticed the same man on the bus – improbable odds, but he was distinctive-looking: a gap-toothed little man who moved swiftly on aluminum crutches. Sometimes our eyes met, and he had fast-moving eyes just like a ticker tape feed, like he was racking numbers inside, taking stock of us all.

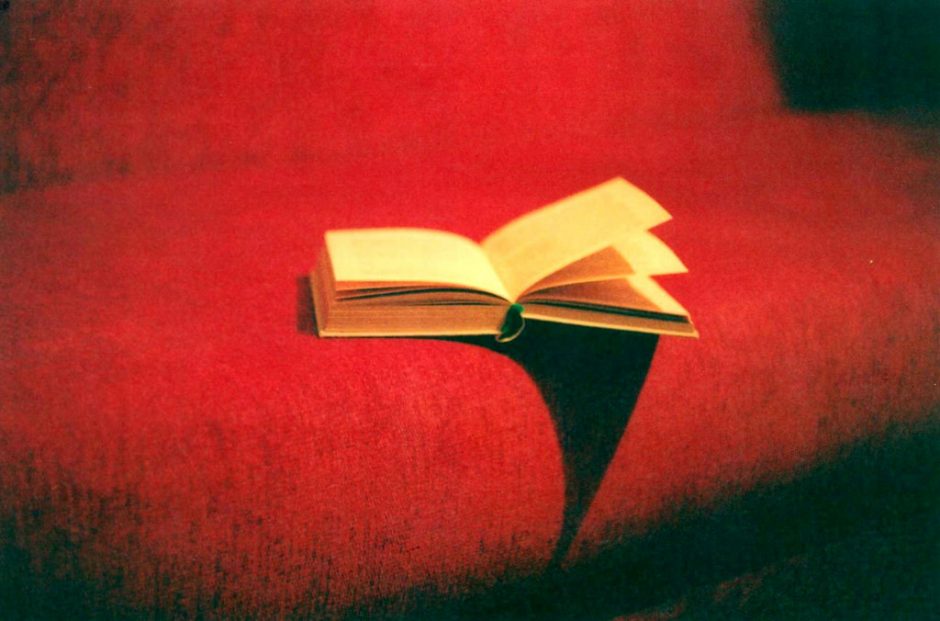

Sometimes I went in through screening with my neighbor to visit Pikachu (what we all called her husband: a corny wisecrack nickname for a round-ish yellow guy) because I loved Pika, too – like an uncle. Before he got locked up, he used to spin me out across their living room dancefloor, since he was the only man for blocks who could really work a salsa, where bachata was king and not my thing so much. But, just as often, I waited outside for her, trying to make myself scarce in the CO staff parking lot. I’d spent enough time on the visiting floor growing up and I knew that she and Pikachu could use the hour to themselves. I settled on a lamppost’s concrete base, happy to disappear in a book.

That day I was tucked in the CO lot reading Chekhov stories when the little man on crutches from the bus came right up to me. He eyed me intently and asked if I had a light. I said no problem and asked could I get a square. His energy was sturdy, like somebody who was used to spending a whole lot of time waiting. He smoked Newport 100s, my old brand. I thumbed my light at him, and he looked at my book. I laughed when he said, “nice taste,” and he told me “The Bet” was his favorite story.

“You know this?” I asked.

“Yeah, I read all that way back,” he said. “I’m Frank,” he offered out his hand.

“They call me Venezuela.” We shook.

I asked Frank how he got into Chekhov. He said it was a long story. I told him I had time, so, he broke down for me his old hustle. He said:

“There’s this place out in Jersey, sells paperbacks wholesale, priced by the yard with the covers torn off. They’re meant for recycling, illegal for resale. We used to buy crateloads – similar to how folks do with secondhand clothes by the pound, but that’s easier: less cumbersome to run with in a bust, less illegal. Books are trickier. In the nineties, my cousin Chucho and I had a citywide stripped book empire.

“We bought a seafoam Econoline at auction, $700 flat: graffitied-up, rusted, two bolts shy of scrapyard, but she ran, and she was roomy. They don’t make them like that these days. None of us had papers, let alone a valid license, and the van was uninsured, too, and needed commercial plates. But we knew a guy in Harlem, got us fake plates, $50.

“We’d always get harassed by cops, but, back then before 9/11, these things seemed a little softer. I’d just tell them I’d left my ID at home, give a fake name and address. Chucho saw my tickets one day – I had just three by then – and they were made out to Juan Pablo Duarte, Ramon Matias Mella, Francisco del Rosario Sanchez. ‘Coño, you’re a real idiot,’ he told me, ‘You got all the founding fathers ticketed!’

“Well, we sold most books for $1, some for $2 – the Stephen Kings, the Grishams. We were stacking money fast. We never cared much for a bank account, so we had $30,000 cash in the one-bedroom we shared. We used to fling it around us in the air, like a couple of rich cartoon men. We thought we were going to be millionaires off of our book-selling hustle.

“But Chucho was a mess. He lost thousands gambling or buying girls or cocaine. He was a fool, I’d always tell him. I would have disowned him early on if he wasn’t blood family, and, after his fool ass lost our van keys he was the only one who could hotwire it. He had somehow worked out the trick to it – beast predated Watergate – so I had to keep that lunk around.

“One day this girl showed up – woman, I mean – petite, brown, with a nose ring, big eyes. She was a professor of comparative literature at Columbia University. She was stacked, but she dressed classy: red wine lipstick, sexy sweaters. She poked around our table, asked if we had any real books. I said, ‘they’re all real,’ but I dug around for some Shakespeare plays, thinking that could be her thing. She shrugged back at me like, ‘oh well.’ I was feeling her, got fuddled. I asked what she was looking for and she said she liked the Russians. I promised I had plenty, just not right on me then. I told her to come back soon. When I tell you, I went swimming through those books out in New Jersey picking every Russian name. When she came back, she asked if I knew those books – I didn’t. But I lied. I set out straight away to reading all of them: Chekhov, Pushkin, Gogol. I was so nuts to impress her, I made sure to track down any other books she mentioned after that: Fanon, Baraka, Kafka, Marx. Whenever she’d come, I’d leave Chucho the stand and take her for coffee, talk for hours. I was wild for her .”

He paused then, trailing off right there. “What happened?” I asked him.

“I saw her with Chucho one day. I could’ve killed him right then. And, then, she stopped coming. I had her landline. But she just never picked up.

“Not long after that, we were in the Lincoln Tunnel, morning rush, and the van up and died on us. Chucho set to jimmying all his steering column wiring, but it was taking too long. Car honking, drivers cursing, and the flatbed tow truck rolled right up with an NYPD squad car trailing.

“Well, we took one good look at ourselves: both undocumented, van uninsured, hotwired to start, fake plates, jam-packed loaded with illegal books for resale. There was only one thing to do. I shook Chucho’s hand; we split. That was that. He went one way, and I went another, moving fast as my crutches go. We left our van right there in the morning rush hour Lincoln Tunnel. That was the end of our business venture as literature salesmen.”

When my neighbor came out and found me, I told Frank “nice to meet you” and said I hoped I’d see him around. I wondered why he was out at Rikers and why he didn’t go in, if he was waiting on someone, too, but I didn’t think too much of it.

On the bus ride back to Queens Plaza to catch both trains back home, my neighbor was usually silent, older-looking than she was. But, this time, she seemed restless, buzzing, and by Astoria Boulevard she was whispering, excited, talking about could I keep a secret.

Pikachu had told her they were planning to go on strike in a coordinated effort with jails and prisons across the country. I asked how they were organizing. She couldn’t tell me but it involved the smuggling in and out of books. The little bit she told me past that, I swore never to share. She grew quiet for a while. She focused out the window. I looked at her lap. When she shifted her weight, her handbag uncovered something that she held, tightly like a Bible, and I realized what it was: a yellowed-up mass market copy of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War with the front cover of it stripped off.

Em Rose is an MFA student at CUNY – City College. She holds a B.A. from Columbia, where her poems appeared in student publications Surgam, Quarto, Proxy, and Fawlt Mag. She was a Fulbright Fellow in Venezuela, researching maroon history. She previously worked as a housing organizer in Harlem and at GOLES on the Lower East Side, where she still works as a grant writer. She's received scholarships from the Bread Loaf Translators' Conference and the Squaw Valley Community of Writers. "The Chemist's Wife" is her first published story.