I arrive to find Keetah standing at her kitchen counter, opening a bag of Maseca. Corn flour is the key ingredient of Mexican cuisine, too, I say. We could make tortillas. Tamales, atole, empanadas, gorditas!

Keetah smiles. “I had a gordita once. At Taco Bell.”

But tonight we’ll be making cornbread, she says. Into a giant blue bowl she sifts the corn flour, eyeballs in some Quick Oats, then mixes them together with the back of her hand. Into a vat of boiling water, she squirts a quarter bottle of Great Value Pancake Syrup, imbuing the kitchen with a delicious warmth. A basket of strawberries are hulled and tumbled into another bowl, where they get mashed into compote, drizzled with syrup, and then folded into the blue bowl. Pushing the mixture to one side, Keetah pours in boiling water from a kettle and forms a hot dough ball that she rolls into a patty. The trick, she says, is to wet it just enough so there are no cracks. Otherwise, the cornbread will break when you boil it.

There is something inherently joyful about dough-foods. How the recipes get passed down through the generations; how they are best prepared communally, with each person assigned her own task. The way your hands wind up sticky and your floor gets good and gritty. The pleasure of transforming something raw into nourishment.

Keetah says there is a special song for cornbread-making, as it is one of the Mohawk’s most revered foods. She sings a few rounds as we roll out the patties. The melody undulates, as if mimicking kneading hands in motion, and caresses, like a lullaby. One by one, we drop the patties into the vat of fragrantly boiling water and wait for them to surface.

![]()

It’s not easy riling Keetah’s little girls out of bed the next morning. However exciting a Longhouse ceremony might be for me, to them, it is an impediment to sleeping in and watching cartoons (a.k.a. church). Keetah dresses them in ribbon shirts and then packs a basket of bowls and spoons. I grab the pot of cornbread as we dash out the door and into her truck. Keetah’s eldest slides in a CD. Adele blasts forth, crooning “Someone Like You.” This awakens the girls considerably. We sing along at the top of our lungs as we charge down Route 37 toward the Longhouse. The ceremony started at 9, but we don’t arrive until nearly 9:30. Indian time, Keetah jokes. If so, we’re not the only ones keeping it. There are barely a dozen cars in the lot.

Gender dictates that we enter the Longhouse through the western door while males walk around the rectangular cabin to enter via the eastern door. Inside is a single, sweeping room constructed entirely of wood, from the polished floors to the bleachers along the walls to the high ceiling dotted with fans. Rattles made of turtle shells dangle beside a triangular window. Hanging pedestals are topped with feathered-and-antlered kastowa. There are two wood-burning stoves, one at each end. Beyond that, the Longhouse feels almost Quaker in its sparse aesthetic.

There is singing and there is dancing and there is chanting, and often all three at once. Two men keep the rhythm with rattles made of turtle shells while the rest of us dance in a long procession around the room. At first, I try to follow the footwork of the woman in front of me, but gradually realize that people are moving to their own internal beat. I do as well, relishing in the freedom. At one point, someone grabs my hand. I look down to find a girl who can’t be more than four staring up at me with unblinking eyes. She is wearing a little white sundress embroidered with strawberries. Her silky black hair is parted into pigtails. She seems to want me to lead her, and so I do, clasping her small hand in my own. Together we travel round and round the Longhouse, along with thirty, then forty, then sixty others. Someone makes a sound like “Yee-oh!” The rest of us respond in turn.

An hour into the ceremony, Keetah exits the Longhouse and I trail behind. Next door is an industrial-sized kitchen where women are preparing the day’s feast, pulping piles of strawberries and sliding them into a bucket of water. Keetah stations me with her Ista (mother), who is making corn mush at the stove. She shows me how to whisk the corn flour and water together until they take on a cream-of-wheat sheen, then add in strawberries and maple syrup.

“Has Keetah told you about Sky Woman?” Ista asks, peering at me through her owl-rimmed glasses.

I recite the Creation Stories I’ve heard, about how Sky Woman fell from the sky one day, landed on the back of a turtle, and walked about sprinkling sky-dirt that became earth-dirt beneath her feet. Ista nods approvingly, then adds another legend to my library. Sky Woman’s husband often tried to test her resolve. Once, he asked her to make corn mush without wearing any clothes.

“See how it’s bubbling?” Ista asks.

I glance down to discover that the mush pot has become a lava pit. A giant bubble bursts, singeing my hand with splatter. I yelp and lower the flame.

Ista laughs. “That’s what Sky Woman’s husband wanted to know. If she could endure the pain.”

No Sky Man for me, in other words, but that’s okay. Around this time next year, I’ll fall in love with a Sky Woman of my own, who heals instead of hurts. But that story is better saved for another day.

Back in the Longhouse, a girl is selected from each clan to distribute strawberry juice. I accept a cup and wait to see if a toast will follow. Sure enough, the chief rises to announce that the strawberry is a leader among fruits. When Sky Woman fell, this was the first fruit she found. Likewise, it is the first berry to reveal itself each spring, paving the way for all the other berries to come. Therefore we must honor this brave berry, giving it thanks for ripening yet again for our health and wellbeing.

With that, the chief tips back his cup. The rest of us do, too. The liquid is tangy but sweet, with just enough pulp to munch.

“But there is a contradiction here,” he says sternly. “We are drinking this healthy, nourishing juice out of plastic cups that have to be thrown away into a landfill that will pollute Mother Earth and eventually our children. We all should have brought our own cups from home!”

Ah, guilt. Not even the animists are spared of it.

Lunchtime. The women from the kitchen pull a long table out into the middle of the room and set it with every strawberry configuration imaginable: jam, shortcake, compote, muffins, mush, and juice, along with stacks of fry bread and several kinds of cornbread, including one speckled with kidney beans. Elders are invited to line up first, followed by guests, women and children, and then men. I carry a steaming bowl of mush back to the bleachers. Ista joins me.

“What else do strawberries signify?” I ask, blowing on a spoonful.

Holding up her cup of juice, she says, “You see its color? That represents the blood of the woman.” Pointing at my mush, she adds, “When you cut a strawberry in half, it also represents the woman. It grows the closest to the ground, so it is the closest to the earth, which is the Mother. That makes it feminine, too. The strawberry is medicine for the woman.”

Years ago, I helped my friend Rachél organize a “menstruation celebration” for teenage girls in Corpus Christi. We delighted over her idea to serve strawberry shortcake with red fruit punch, but when I shared this menu with others, they thought it kinky. So it’s gratifying to learn that Rachél’s instinct was right, that strawberries really do symbolize the feminine, and have been celebrated as such by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) since time immemorial.

After lunch, we dance again. As the turtle-rattles pound a rhythm into my brain, I feel increasingly elated. Men emit their “Yee-ohs!” Footwork gets fancier. Sweat trickles down our faces. Someone whoops; someone hollers. Not for a god. Not for a prophet. For a berry. Something that leaves behind sustenance instead of commandments. Something that offers a single interpretation: plant and water and harvest me, and I will return. Poison me, and I won’t.

One song ends and another begins. More rattles, different rhythms. Round and around the Longhouse we go. Drinking the symbolic blood of women. Eating the gifts of Sky Woman. Another whoop, another holler. Euphoria swirls through the procession.

The chanting stops and starts again. New song. New rhythm. Same motivation. The valiant strawberry. To say you “almost tasted strawberries” is to say you narrowly avoided death. The skyway above is lined with the fruit. You can pluck as many as you want from the patches.

Hours pass. Days, even. Then all too soon, the music ends. A final whoop, a last “Yee-oh!” and we all clamber back into the bleachers. The chief removes the wampum hanging on a nearby stand and holds it to his heart. Again, we are treated to the Ohen:ton Karihwatehkwen, The Words That Come Before All Else. We thank the Earth Mother and the waters, the fish and the plants, the animals and the trees. We thank the four winds and the thunders, the sun and Grandmother Moon, the stars and the Enlightened Teachers. We thank the people. We thank the Creator. Ehtho niiohtonha‘k ne onkwa’nikon:ra. And now our minds are one.

As we exit the bleachers for the last time, Keetah is stopped by a cousin. They talk a moment, then turn to me for introductions. When I mention being from the southern border, he rubs his chin.

“You heard of the Minutemen?” he asks. “They tried to come here five or six years ago.”

“Really?” I ask. “What happened?”

“The Border Patrol told them they’d get their asses kicked, and they left.”

He and Keetah exchange a knowing laugh. Of the many things I admire about Akwesasne Mohawks, this is chief. They own their own power.

Glancing at my phone, I am startled to see it is 2 p.m. We have been here for nearly five hours. My moving van arrives in the morning. I grab a broom and start sweeping around the women packing food, the men moving tables, the children eating popsicles. Gradually the crowd thins, until only Keetah, her daughters, and I remain. I return the broom to its corner. Keetah flicks off the lights. Together we pull the wooden door closed. When I search for a way to lock it, Keetah says there’s no need.

“Are you sure?” I ask, thinking of all the feathered headdresses and turtle-rattles inside.

She nods. “This is a sacred space. Our community respects that. We keep our doors open.”

We drive back to Keetah’s in the rain. No Adele this time. We want to preserve the resounding rhythms in our brains. There’s my car, sitting in Keetah’s driveway. I step out and embrace the girls, one by one. By the time I reach Keetah, I have grown so emotional, I don’t know what to say. In the past year, she has given me time, story, knowledge, friendship. She has shown me not only her self, but my own self. I still feel fractured somehow, but if I’ve learned anything at Akwesasne, it is that you can still be united while divided.

These are the words that come before all else: Gratitude, gratitude, gratitude.

They are all I can say and everything I can say.

And so I do.

![]()

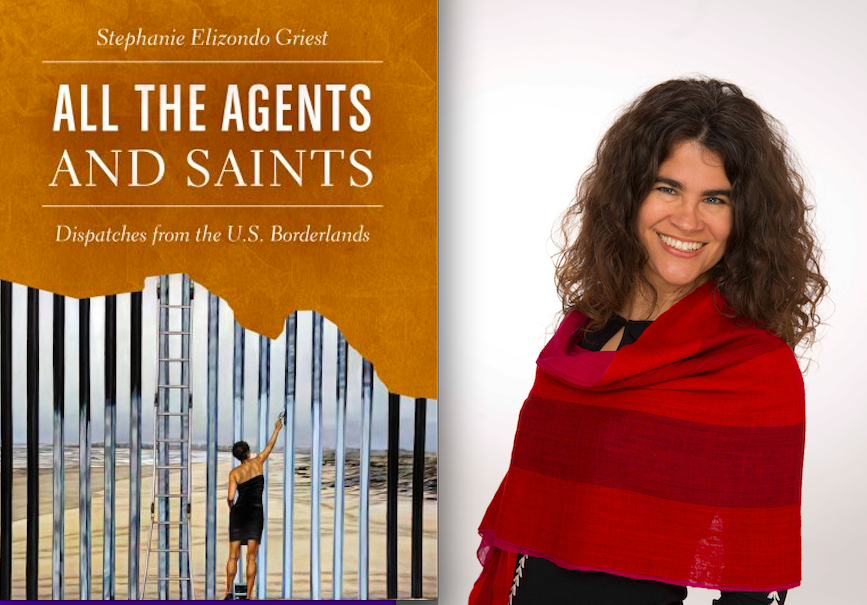

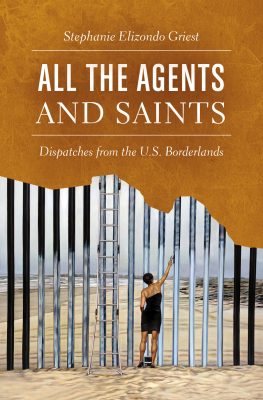

Editor’s Note: This excerpt—snipped from the final chapter of All the Agents & Saints: Dispatches from the U.S. Borderlands (UNC Press, 2017)—takes places at the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne, which straddles the New York/Canada borderline.

The author arrives at her friend Keetah’s house for a final visit, the night before a special Longhouse ceremony in honor of the first strawberries of the season. Ohen:ton Karihwatehkwen is the name of the traditional Thanksgiving Address given by Mohawks before and after every meeting of significance. In English, it means “The Words That Come Before All Else.”

![]()

From All the Agents and Saints: Dispatches from the U.S. Borderlands. Copyright © 2017 by Stephanie Elizondo Griest. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.org

Buy All the Agents & Saints: Dispatches from the U.S. Borderlands

Image Credits: University of North Carolina Press

South Texas native Stephanie Elizondo Griest is the author of All the Agents & Saints: Dispatches from the US Borderlands; Mexican Enough; Around the Bloc: My Life in Moscow, Beijing, and Havana, and the guidebook 100 Places Every Woman Should Go. She has also written for the New York Times, Washington Post, VQR, Believer, and Oxford American and edited Best Women’s Travel Writing 2010. Her coverage of the borderlands won a Margolis Award for Social Justice Reporting. She is Assistant Professor of Creative Nonfiction at UNC-Chapel Hill and can be found at www.StephanieElizondoGriest.com and @SElizondoGriest.