“A

lternate street parking has been cancelled today.”

Mina’s radio in Brooklyn and mine on Sado Island in my mother’s kitchen are tuned to the same station every day we are apart. It’s Wednesday night in New York where Mina is in the present and Thursday morning in Japan where I am fourteen hours in the future. We listen to weather reports and talk radio, short stories and jazz. I know the days when she has to move the car to the other side of the street or when she has to take an umbrella to her job at the Museum of Paper on the Lower East Side.

On our honeymoon we visited Japan. It was her first time. It was the last time I saw my mother well. I wanted to introduce Mina to the people and all the places from my childhood. I wanted to have new adventures with her too.

Konnichiwa.

Mina’s greeting to the proprietor of the hotel as she passes the front desk. She is smiling as she does most mornings. She is surprised people can understand her. For months she has studied Japanese listening to Pimsleur cassette tapes from the public library. She practiced speaking my language and writing kanji on my computer with Rosetta Stone. We watched the movies of Ozu and the television serial drama Oshin. She read books, articles, travel guides. She can repeat several key phrases of Japanese without my help.

What is this? I don’t understand? What does this mean? My name is Mina. She knows the words for beautiful kire, delicious oishi, thank you, arigato and please please please.

We take the train into Tokyo. I want to show her special places. Hotel Okura is frozen in the opulent sixties. Sitting in the lobby is like being on the set of a James Bond movie. It isn’t flashy. There is a quiet glimmery elegance. A golden light emanates from a cluster of pendant light fixtures that glow like soft sunlight from a string of necklaces extended from the ceiling.

A young woman wrapped in a pink kimono with a red obi sash, seems to glide past in white wooden geta and snow-white split toe tabi. Mina’s eyes follow the red obi with delight and I know she will look even more beautiful in one of my mother’s handmade kimono. The lamplight warms the polished wooden pillars and narrow beams of the ceiling. It’s been fifty years since Yoshiro Taniguchi designed the building. Royalty, heads of state, rock stars and divas have slept and dined here. Their signatures are on the wall. Jessye Norman, Ella Fitzgerald, my favorite singers, among them. We sit at a low round laquered table, surrounded by five petal shaped chairs. An enormous bouquet of cherry blossom branches commands the attention of every visitor who enters the lobby.

It’s spring and beginning to snow outside. Pale pink cherry blossom petals fall from the clear blue sky. There is a word for this, hana fubuki. We heard a young boy screaming, “Sakura. Hanafubuki. Hanafubuki” over and over. The wind blew a delicate snowstorm of petals all around him. Cherry blossom season is a feeling and also an epic social event. Ueno Park is packed with people celebrating. The air is sweet perfume under the cherry blossom trees. It reminds me of my mother’s Ukiyoe print of a cricket listening party that hangs in her bedroom. In old times people would take bento box picnics and gather near the river or in the forest and parks to experience the sounds (crickets) and sights (flowering cherry blossoms) of spring.

On Sado Island Mina and I went by mistake into a forest known as a place where young people go to commit suicide. It was a very calm place. So quiet in fact that we stopped to listen to the wind. All I could hear were our hearts beating and the rain falling on our hair. Mina didn’t mean to kill the snake. She was scared. She didn’t know that snakes are messengers of the gods. She tried to speak. Her mouth was full.

Take me home Uchi ni kaeritai yo

I want to go home Wasahi mo kaeritai

When our son was born I tried not to think about the accident with the snake. He stopped breathing a few days after he was born. We both wanted to return to the forest and die.

If there had been a forest in Brooklyn we would have laid down on a bed of pine needles and curled against each other on the cold wet ground in the snow and waited for death to come. Instead we lived. We grieved. We stayed in Brooklyn and we buried his tiny body. We clothed a stone baby. Then my mother died suddenly and there was more grief. I had to return home. I was the eldest son and had inherited the house from my childhood. My mother had turned it into a bed and breakfast for tourists. A guest house for visitors.

In Brooklyn Mina is preparing dinner and I’m making a Japanese breakfast for the guests, tourists from Hawaii. Mornings alternate with American style: Pancakes, maple syrup, eggs and bacon. Japanese style: Miso soup and dried fish. We are listening to the same radio. I can almost hear her heart beating.

From my window I can see a rice field. Every kind of green colors the farmer’s fields. I smell fish, a briny smell. The sea breeze stirs the curtains at the kitchen window. My mother lived in this house from the time she married. I was born in this house. From the street below, to the entry of the house, the tiled staircase is steep. A stone lantern sits by the wooden gate that opens into the yard. A stone path leads to the door. The door makes the sound of a bird when it opens. The place for the shoes. The step up into the entry. Past the bathroom, to the left into the kitchen. The two bedrooms on the first floor are tatami rooms where the tourists sleep. There is a western style living room in between the two bedrooms. A floral sofa and big comfortable chairs, a TV, dark wood, bookcases. Framed photos of my mother in formal kimono and a few of the brides she dressed. That was her work, making brides beautiful on their wedding day. On the second floor there are two rooms and a bathroom. I sleep in the bedroom from my childhood.

The earthquake shook me kilometers away from the center. The aftershocks unsettled me. Tremors haunted me even when the earth was still. The tsunami drowned thousands of voices and reached the whispering branches and singing hills. Even the stones are weeping tonight.

Cutting the grass one day, I notice a snake on the small shrine in the backyard. I leave rice and sake and sometimes an egg as an offering. Sometimes I pray. Mina visits in summer when she has vacation time. She swims in the sea at night.

Mina and I have a girl now. She is seven years old and very American. She doesn’t understand why we have to be separated. She wants to be with me in Japan and she wants to be in Brooklyn with her friends. We listen to the Children’s Hour together and I know when it’s time for her to run outside into the backyard, throw herself on the ground and make angels in the snow. This summer she will visit for the first time. Until then, I leave offerings to the messenger from the gods and the sea shimmers between us.

click on image to view PDF

(click here to download, right click and

open in new tab if having difficulties)

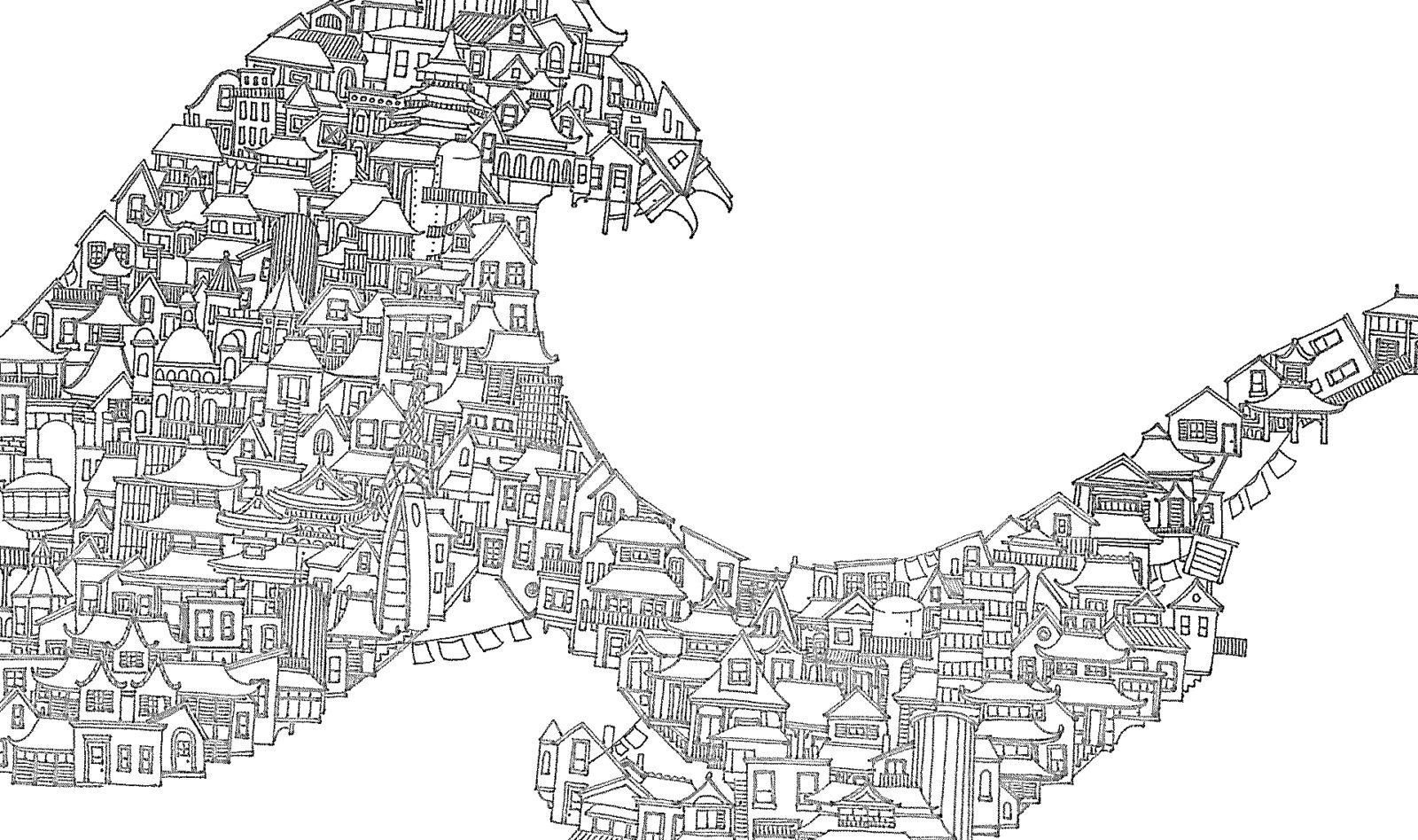

Artwork by Adrienne Brown Impossible Landscape Wave

Georgia born writer Shay Youngblood is author of the novels Black Girl in Paris and Soul Kiss (Riverhead Books) and a collection of short fiction, The Big Mama Stories (Firebrand Books). Her published plays Amazing Grace, Shakin' the Mess Outta Misery and Talking Bones, (Dramatic Publishing Company), have been widely produced. Her other plays include Square Blues, Black Power Barbie and Communism Killed My Dog. She is the recipient of numerous grants and awards including a Pushcart Prize for fiction, a Lorraine Hansberry Playwriting Award, an Edward Albee honoree, several NAACP Theater Awards, an Astraea Writers' Award for fiction and a 2004 New York Foundation for the Arts Sustained Achievement Award. Ms. Youngblood received her MFA in Creative Writing from Brown University and has taught Creative Writing to faculty and graduate students at NYU and has been Visiting Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi and Texas A&M Universities. She was recently awarded a National Endowment for the Arts sponsored Japan-US Creative Artist Fellowship for 2011.