Today, our bookstore experience consists of muzack and a too-large children’s section smothered in pastel colors. We wander around absentmindedly, swirling our barista-made coffee, and kill time before we have to go a movie down past the mall’s large pavilion. We might buy a book. Or make a note to buy something online later. Generally, we leave as calm as we entered, not a seditious thought in mind. We don’t think of bookstores as political spaces. They are places of capitalism and consumption, as personality-full as anything branded for mass-appeal. And we seem to like it this way.

When we do think of political bookstores, we sometimes think of famous ones like Galignani’s in Paris or Hatchard’s in London. Bibliophiles flock to see where the Brontes first sold a novel, or where Flaubert held a book signing. Choosing to sell unpopular books, banned texts, underground and foreign manifestos—these were the political powers contained in these musky basements and windowed storefronts. It is one thing to wander around a Barnes & Noble in 2013, another to wander through the aisles of Marcus Books in 1967. Macus Books?

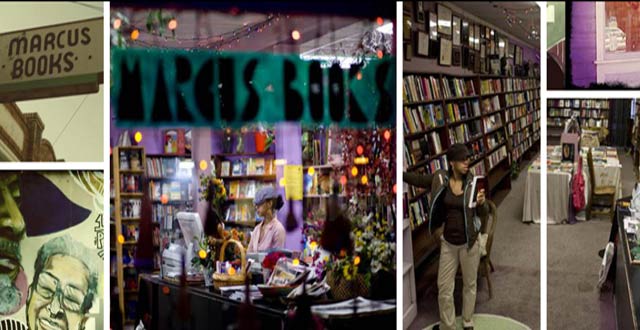

In 1959, Raye and Julian Richardson founded Marcus Books—what they believed to be the first African American bookstore in the United States. But now, fifty-four years later, the San Francisco shop faces eviction in the quiet aftermath of the housing crisis.

Supporters cry that the stakes have never been so high, that the new landlords should not evict its bookish tenant, that the shop has been a symbol of culture and peace for a youth quickly succumbing to poverty and violence.

While bookstores in Europe gave rise to revolutions in the early 20th century through the dispersal of incendiary texts, in the mid-20th, Marcus Books gave representation to voices usually unread.

From KALW.org:

The concept of “Black Power” found deep roots in the Bay Area’s literary world. Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, Ishmael Reed – as they emerged from the black arts movement, they needed a place to be heard, for their words to be read. That place was Marcus Books, in San Francisco’s Fillmore district – once known as the Harlem of the West.

Macus Books fights to stay open. But, even if this battle is won, the war will be lost. The digital opponent is too big.

Today, bookstores are disappearing. We’ve known this for twenty years. In the 1990s, we saw the mom-and-pop establishments replaced with national chains like Borders, Barnes & Noble, Waldenbooks, and, of course, Walmart. But now, the book business has moved online. Save college campuses, where bookstores must carry the required books, most book purchasing today happens with the click of mouse.

In 2012 (through Nov.), 43.8% of books bought by consumers were sold online versus 31.6% sold in large retail chains, independent bookstores, other mass merchandisers and supermarkets. This is nearly a direct reversal of the situation in 2011, when 35.1% of books were sold online and 41.7% were sold in stores.

While this world-wide trend continues unimpeded, the only groups signaling alarm seem to be bookstore owners and a few loyal customers. I am part of the group that has migrated to the internets. I use Amazon, Abe Books, even eBay to score books –mostly because I’m lazy, and I don’t really have it in me to head to the local strip mall for a book.

But, I can’t help but think that we’re making a huge mistake. That the loss of the bookstore echoes our like-button (lack of) political activism. We’re staying at home instead of sowing new thoughts. We don’t go to feminist bookstores and get lost in Judith Butler anymore. We don’t wander aisles brushing our fingers against spines bearing names of unheard-of authors. We’re losing the anarchist bookstore that proudly sells local zines for a dollar. And other than convenience, I’m not sure we’ve gained anything in return.

Karen Johnson is the daughter of Raye and Julian Richardson. Marcus Books was her childhood playground, her second home.

“If my parents hadn’t read that much, I would not have. If they hadn’t made me go to the bookstore after school, I would have gotten into some mess. And I don’t know if I would be alive today.”

There’s a lot more to this than simply killing time at the mall.

image courtesy of Marcus Books and Bowkers Books

Ramírez won the inaugural PEN/Fusion Emerging Writers Prize in 2015 for her nonfiction novella, “Dead Boys” (available as a Kindle single from Little A). A nonfiction writer, storyteller, digital maker, critic and performance poet based in Pittsburgh, she is working on her first full-length book, “The Violence” (forthcoming from Scribner).