I met Jennifer Clement for the first time in 2011 while traveling with the Iowa International Writing Program to Uruguay and Bolivia. On the tour we spent all day visiting writers, students, teachers and the next morning she would unabashedly say that she had stayed up late translating Mexican soap operas into English for the Chinese and Russian market. During that tour we became fast-close. Instant friends. And since we have been in conversation about feminism, writing, love, men, children, motherhood and our responsibility as writers. When I confessed that I was losing faith while writing my third novel, she took both my hands and said, “What can we do? Writers write. Keep writing.” We were in NYC, in Greenwich Village at a café. She was dressed in black, her hair a striking halo, her voice assured, her eyes and ears tuned in. When you sit with her she makes it clear that she is more interested in others than she is of herself.

This interview began from the moment we met, the emails we have shared and a more recent series of questions I sent her after she was elected as the president of PEN International.

Angie Cruz: First off I wanted to congratulate you on being elected as the new president for PEN International. As I understand it, you are the first woman to be elected? What does this mean for you and also for your work as a writer?

Jennifer Clement: It’s an honor, because the people who voted for me are some of the most exceptional people in the world. Many of them live in exile, have been tortured, live in fear or have given their lives and resources to defend freedom of expression. It’s incredible to think that we are all working pro bono for an important cause, which makes PEN unlike any other NGO.

AC: Why is it important for you to do this work at this time in your career as a writer?

JC: Actually it does not have to do with this time at all. I’ve been a member of PEN for 22 years. I was president of PEN Mexico from 2009 to 2012 and my work focused on the killing of journalists. When Sweden, South Africa and Mexico nominated me to be president of PEN International I accepted because I saw it as a continuation of my previous work both as an activist and as a writer.

AC: What are your responsibilities now that you are president?

JC: It’s a challenge because I have to address problems from all over the world. In this first month I have already had to focus on the killings in Bangladesh, the state of journalists in Honduras with one case in particular, the death sentence of poet Ashraf Fayadh in Saudi Arabia and the imprisonment of Ilham Tohti in China, to name a few. I also have a lot of travel ahead.

AC: Much of your work has put front and center the issues women in marginalized communities face everyday. Your fiction in particular has been critical of patriarchy, the United States’ position on guns, etc. As the new president of PEN, what’s on your agenda?

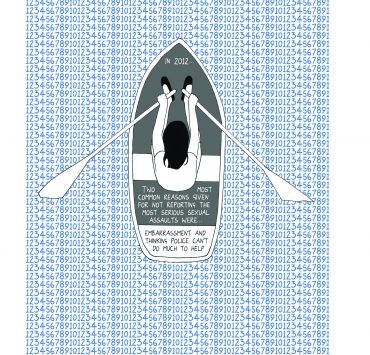

JC: I will have to change the PEN Charter, which is a profound and important change. At present, a part of the PEN charter states that: Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world. – See more at: PEN charter As you can see, gender is missing. I think it is important for PEN to think of gender violence as gender censorship. The United Nations Development Fund for Women estimates that at least one in every three women in the world has been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused. In some countries the rate is as high as 70 percent. Globally, violence is a greater threat to women aged aged 15-44 than cancer, traffic accidents, malaria and war combined.

AC: You have spoken before on the power of fiction, what else do you think needs to happen, besides writing, to complicate singular narratives of any given people?

JC: The history of the novel shows us that our differences are what unite us and that fiction helps to create empathy and compassion. There needs to be more translation. If you don’t write in English it’s hard to get your books out there. PEN does a lot of work on this front.

AC: Although I am of course thrilled about your new appointment I fear that with your new responsibilities your writing career may have to be put on pause. Do you have a book project in the works?

JC: My new novel is about gun violence. I hope to finish it in the next few months. It takes place in contemporary USA and Mexico. It forms the second half of a diptych with my published novel Prayers for the Stolen. It examines gun culture in the USA and how guns are brought into Mexico. The latest studies have found that nearly 50 percent of U.S. firearms dealers depend on business from the legal and illegal U.S.-Mexico gun trade for their economic survival. (Here is the link to this study: Mexico Gun trafficking.) My interest in gun violence and legal and illegal trade is longstanding. I have interviewed survivors of gun violence including a teenager who survived the 2012 Colorado massacre during the Batman movie premier. My own published essays on the topic include The Church of Gun and Machine Gun Bouquets. I have also visited the NRA premises and NRA gun museum in Virginia as research for this book.

AC: Could you say something of your writing process? When do you work?

JC: I only have a strict schedule when I am working on a book. I always get up before sunrise and work for three hours. I love the silence of that time of day. I never check my email or look at the news online until the three hours are over.

AC: Can you share with me your process in writing the novel?

JC: For Prayers For The Stolen, I spent the past ten years speaking to Mexican women who are victims of Mexico’s violence, but I don’t even call it interviewing. I call it listening because it’s coming from a different place, a more compassionate place perhaps- closer to friendship then journalism. I interviewed the girlfriends, wives and daughters of drug traffickers to learn that Mexico is a warren of hidden women. They hide in places that look like supermarkets or grocery stores on the outside, false façades; in the basements of convents, where women live with their children and have not seen daylight for years; and in privately-owned hotels that are rented by the government — a surreal, Third World concept of a Witness Protection Program.

AC: How will you balance between writing and working for PEN?

JC: I plan to write poetry. It’s easier for me to concentrate in short bursts on poetry than on a novel.

AC: Who are the writers that you think we should be paying attention to right now?

JC: I’m always awaiting books by Kirsty Gunn. She’s a wonderful writer. I’m also very much looking forward to Chigozie Obioma’s new work.

AC: I am curious what your thoughts are on the MFA programs in the United States and the state of “American” fiction. You recently finished an MFA in the United States, what was your experience?

JC: I had a very positive experience at my MFA program because I was not looking for praise. I wanted to learn. I think it all depends on the teachers you have. My experience was that often the “popular” teachers were those who coddled their students. This may be a worrisome trend in higher education.

AC: Your last publication, Prayers For The Stolen, and also a prior book, Widow Basquiat, have in many ways crossed you over as a writer to readers in the U.S. But you have been writing for decades as an American-Mexican (How do you identify?) having lived the majority of your life in Mexico including childhood.

JC: In the USA there’s a lot of discussion as to one’s identity, which too often underscores our differences rather than our similarities. I think of myself as a citizen of the world in many ways but Mexican above all.

AC: You have faced many challenges as a writer. What is the best advice you have received to motivate you to continue?

JC: The best advice I had was from W.S. Merwin who said, ” always write for the book”. He was speaking to intention.

AC: How can writers and readers support PEN and the important work they are doing?

JC: Writers need to see that there are many things at stake for us. The first is loss of freedom of expression, which is happening in many parts of the world to terrible consequences. Freedom of expression equals knowledge. It is an equation. We are also facing, as writers, a threat to copyright laws. The digital revolution is placing copyright in grave danger. PEN addresses and fights for these issues as well as honoring the place of literature. I urge everyone to support PEN through our Readers Circle. Unlike any other NGO in the world, everyone works pro bono in over 150 centers worldwide. PEN is also the world’s first human right’s organization. The link for supporting PEN: http://www.pen-international.org/circles/pen-international-readers-circle/

Jennifer Clement is President of PEN International and the first woman elected to the office in almost one hundred years. She has written many books of poetry and novels that have received acclaim in Europe and Latin America but it wasn’t until 2015, with her book, Prayers for The Stolen, did she break in to the United States. She moved to Mexico as a toddler and stayed there up until high school. Her father an activist and engineer, her mother a painter. She admits that her literary traditions are rooted in Latin America and Europe first, then the U.S. She’s disciplined and fearless in her writing. Her primary research for her novel, Prayers For The Stolen wer her countless hours she spent visiting the prisons and getting to know the women of Guerrero, Mexico. “When we think of narco trafficking we often think of men, but the women, who is paying attention to the women?”

She currently lives in Mexico City and often visits her two children in New York City, a city she knows well from her time as a NYU undergraduate. It was during that time she witnessed up close the rise of Warhol, Basquiat, Madonna. Decades later she eloquently captured that important historic moment in her stunning memoir, Widow Basquiat. Her first novel, A True Story Based On Lies, was published in 2002 and was a finalist for the Orange Prize. After she wrote, The Poison That Fascinates, published in 2009. Both received enthusiastic reviews and were well known in England but never sold in the United States. In 2014 Prayers For The Stolen was sold in a preemptive sale, translated into 27 languages, prominently reviewed and a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award. She is also now an Advisory Editor for Aster(ix).

Angie Cruz's novel, DOMINICANA is the inaugural bookpick for GMA book club, and the Wordup Uptown Reads selection for 2019. It was also longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie award in excellence in fiction for 2019. It was named most anticipated/ best book in 2019 by Time, Newsweek, People, Oprah Magazine, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Esquire. Cruz is the author of two other novels, Soledad and Let It Rain Coffee. She's the founder and Editor-in-chief of the award winning literary journal, Aster(ix)and an Associate professor at University of Pittsburgh where she teaches in the MFA program. She splits her time between Pittsburgh, New York, and Turin.