Watch Alex Rivera’s A Robot Walks Into a Bar at FUTURESTATES

Armando García: I would like to hear your thoughts regarding last year’s public’s response to the Smithsonian’s Latino exhibition, “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art.” I myself had not seen the exhibition, but I have read the online discussion with Philip Kennicott and his review of the exhibition. I also saw your Facebook status post from October 30, 2013, and read the massive amount of responses that you received regarding the review. Could you tell me a little bit more about how your response to Philip Kennicott’s article came about?

Alex Rivera: It started for me just like any other evening on the internet, I was reading my feed when I saw a lot of people circulating a review of a new exhibition at the Smithsonian called “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art.” The review was very critical of the show. What caught me off guard was that the critic, Philip Kennicott, went so far as to proclaim “Latino art is a meaningless category.” He also used the review as a space to criticize the Smithsonian broadly for “pandering” to various interest groups. The review, to me, crystallized two tendencies that seem to emerge around exhibitions of Latino art, and those are one: the impulse by white critics to not dialogue about the art or the specificity of the show, but instead to question the entire project of identity brought into the curatorial matrix, and the other being to use these shows that celebrate and organize the work of historically marginalized groups, as an opportunity to say that these same groups have undue power and influence and are forcing institutions to pander to them. The Washington Post review was special to me because it was so blatant and so clear on both of those fronts.

García: Actually, it might have been your Facebook post that prompted me to read Kennicott’s review to begin with. When I read it, there are a couple of things that your comments right now pointed me back to regarding (a) how he was reviewing the exhibition as a whole, and (b) what terms he was using to define the review itself, meaning the terms that he was using in his review to discuss the exhibition.

One of the things that he says is the following: “It isn’t a bad show, but surely work made by artists who belong to the more than 50 million people who identify as Hispanic or Latino in the United States is more vibrant, provocative and interesting than what is on display here. Surely there’s a more compelling way to present it, and more interesting things to say about it.” After he describes a few the endorsing blurbs from the exhibition’s catalog, he says: “This isn’t just the usual academic blah-blah, but a telling symptom of an insoluble problem: Latino art, today, is a meaningless category.”

The rest of the review, in my opinion, seems to be about his own dilemma with trying to wrestle with knowing or not knowing how to talk about a form of art (“Latino art”) that is not already set within a frame that he can understand. He references a politicized art, or art that is targeting the politicization of Latino groups, and he has a problem with anything that is not that. Hearing from you right now, it seems to me that there are two issues at stake here: on the one hand, there is the response from art critics who are not necessarily talking about the art itself, but are instead using the review as an opportunity to use both the review and the exhibition as an opportunity to categorize Latinidad and to categorize what “Latino” means; and the other hand, which is derivative or complementary to the first, is that Latino artists are actually cut out of it because their reviews are not about the artists and they’re not about the art itself either. You are saying that Latino artists are used to this kind of treatment. Could you talk a little bit more about that? Given the two ideas that I just pointed out, how is it that Latino artists respond to these reviews?

Rivera: A few years ago there was a show organized around the concept of “art after the Chicano Movement,” “Phantom Sightings.” That show, in some ways did what Kennicott is saying should be done because it did not look at all of Latino cultural production, it’s only looked at Chicano cultural production and post-1970s, and so it looked at a smaller sliver of U.S. Latino cultural production. Nonetheless, when that show was reviewed in The New York Times, the very first line of the review was “Is it time to retire the identity-based group show?” It was the first line.

The issue is that these shows are one component of a process that opens up imaginary spaces of credibility and material spaces of marketability for artists. So when reviews come out time and time again that don’t discuss the specific impulse of the curator and don’t discuss the specific artwork, but instead launch a kind of philosophical debate around the nature of identity, around the coherency of these identity categories, when that happens it’s a real violence and a disservice done to the artists, and to, in this case, Latino participation in American cultural life. We’re not talking about an isolated incident; there’s a pattern of these kinds of reviews in response to these kinds of exhibitions.

García: Yes, definitely, I’d love to read them. In preparation for our conversation today, I focused particularly on that Kennicott’s review itself and the responses to it. One of the things that I kept thinking about when reading the review—and I would love to see what the other reviews look like—was the terminology that is being employed to talk about the exhibit. After your Facebook post from October, you followed up with an email conversation with Kennicott that he then published in The Washington Post. In that conversation, you asked him very directly: did he have a problem with the question “Latino art” or with the notion of “Latino” itself? When he answered, his response did not actually address your question, right? He first answered it by clarifying what he meant by “there is no such thing as Latino art.” However, I think that your question to him was aiming towards a different conversation regarding what he was understanding as “Latino,” not necessarily as a “here’s an example of Latinidad,” but about how he understands the term “Latino”; after knowing what he means by “Latino”, then you could’ve talked about what he means by “Latino art.” His answer didn’t try to address that either, right? He was talking more about defending himself when he spoke about Latino art. In reading his responses and his review, and maybe “ambivalence” is not the correct word to use here, but what I sensed from him was more of an ambivalence towards his lack of understanding and lack of knowledge of Latinidad. What prompted him to say that Latino art is a meaningless category was that the Latino art exhibit refused to include a definition of Latinidad that he could understand on his own terms. The exhibition’s resistance to include a neat categorization and labeling, rather than leading him to think critically through this resistance, led him to dismiss “Latino art” because it doesn’t refer to a cohesive collective that he could understand as universally known. There are so many different differences between Latinos that you can’t talk about a Latino art because of said differences. In my opinion, he was trying to use the term “Latino art” without actually wanting to talk about the very notion of Latinidad.

Rivera: These shows are extraordinarily rare, and then when they occur, what we see is a pattern of non-minority reviewers launching a sort of an ontological or epistemological, exploration of the integrity of a category like “Latino,” and their argument being that this category is so broad that by grouping people together under it you’re only reinforcing these vague racial schemas, and the show is essentially nonsense because the category that’s organizing it is too broad. The incredible irony is that these shows take place in institutions like the Whitney, whose full name is the Whitney Museum of American Art, or the Smithsonian, which is the Smithsonian Museum of American Art. If we look at that collection of words with the same curiosity and the same desire to interrogate that these reviewers are using, then we have systemic, epistemic collapse. “America” is always, constantly and forever going to be a more useless word than “Latino.” “Latino” is a subset of “America.” As much as Philip Kennicott can’t wrap his mind around 50 million Latinos and a kind of cultural unity there, well this show is occurring inside of a museum called “American,” and “American” would be a reference to 350 million people. How is it that we can be comfortable with terms like “Museum of American Art,” which is a term that so many places deploy and it just sits there, kind of quietly, invisibly, and no one says “this is a ridiculous notion to have a Museum of American Art, it’s too vague”? Of course not, and that to me, actually digging down that line, leads to the greater truth, which is that there are culturally-specific spaces all around us: there is the Museo del Barrio in Spanish Harlem, there is the Galeria de la Raza in San Francisco, there are Latino film festivals, there are Latino literary journals; there are Latino cultural spaces all around the country, and someone like Philip Kennicott and these reviewers would not take the time to write about them and discredit them on a philosophical, political or art historical basis. They wouldn’t write that the Museo del Barrio shouldn’t exist, because Latino art doesn’t have meaning. But when Latino art is brought into the Whitney, or brought into the Smithsonian, or the Museum of Modern Art, or when Black art is brought in, or when Women’s art is brought in and organized in those types of powerful cultural spaces that make or break careers and that become part of the long-term historical record of what is America, it’s when these identity-group shows are brought into those central spaces that all of a sudden there is a kind of eruption of philosophical inquiry into these terms. I think that the inquiry is not based on intellectual merit – it’s based on a feeling of threat and territoriality. It’s not that the category of “Latino” has “no meaning,” I think that these writers don’t really care about that conversation. It’s only when Latino artists organize in these central spaces, in which power is concentrated and produced, that all of a sudden a kind of philosophical crisis is invented. “These words are too complicated! These categories are too broad!” Come on.

The last thing I’ll add along this line of thought is that these are writers that are very comfortable with phrases like “modern art” or “abstract art.” How is it that “modernity” is a more specific term than “Latinidad”? It’s really a ridiculous notion. “Art” itself is a nearly indefinable word. What is and isn’t “art”? There’s no clear borders around that. The difference between art and architecture, the difference between art and industrial design, the difference between art and commerce, the borders even around those signifiers are very slippery, and if you were to interrogate them fully then you couldn’t even think about the museum. The whole thing is very tenuous in its core. Why it is that critics like Kennicott are comfortable with notions of “art,” notions of “modernity, “abstraction,” “American art,” etc., but “Black art,” “Women’s art,” “Latino art,” all of a sudden those words and those concepts need to be drilled into and questioned and made into a problem.

García: I hear what you’re saying about Kennicott, but to be honest, after reading the essays and reviews, I think that it is precisely the opposite of wanting to have that kind of conversation, even with himself. When he talks about Latinos there is a line that comes up in his review and in the NPR interview with him where he says: “Does a Cuban artist trained in Paris have anything in common with a Mexican immigrant artist in L.A.?” To me, that kind of response points to what you said regarding territoriality, because in his use of the term “Latino” he is thinking of Latinidad in terms of geography. Does he know the difference between a U.S. Latino and a Latin American from Latin America living in Latin America? I would like to understand if he is conflating the U.S., Latin America, Spain, and their different identities into one category in his conception of Latinidad. The Smithsonian’s “Our America” exhibition was about U.S. American Art, right? It was not about “how do we talk about Latin American Latino art?” It was specifically about American Art, that is the full title of the exhibition. In reading him, I don’t know if he understands who are the 50 million people that he states in the review. Where are they? Where are you talking about? What people are you conceiving as Latino that you find such a big difference between your conception and the Smithsonian’s? Are you even talking the same group? I am not sure if he knows that. When I was reading the interview between the two of you, I sensed a hesitance to address the fact that he doesn’t know and he doesn’t have a clear conception of Latinidad. And because he doesn’t understand it, he relies on very generalizable comments like “50 million people,” “Hispanics,” and “in the U.S.” These are terms that could either identify a particular group or be a complete and total misnomer. Instead of addressing it directly and stating, “This is what I understand as ‘Latin’” he turns the conversation to avoid it altogether and dismiss it at the same time. Am I making sense?

Rivera: Absolutely. It would be as if a restaurant reviewer was reviewing a French restaurant and decided to question the territorial integrity of France and its imperial history. Like “what is ‘French’ cuisine for an empire that has controlled territories around the world?” It is to me a kind of bait-and-switch that’s occurring where there’s a show of Latino art in the Smithsonian and instead of looking at the objects that are there, and the way they’re organized, and the type of specific story that the curator is trying to tell, whether it is succeeded or failing based on their intentions, and whether the individual works are fascinating or not, the entire focus – the beam of light– is moved to another place where the critic is now instead having a conversation about whether or not Latinos exist, about whether or not thinking of this grouping of people has any kind of intellectual merit. And the preordained answer is “No, it’s too big of a group to have any kind of unity, so why would you gather their art and stick it in this museum?”

García: I see what you’re saying: the minute that anything that is not presented as universal, meaning that is not designed for and addressed to a universal—whatever it is that you want to call it, call it “the museum,” call it “art,” call it “modernity”—anything that is not addressed to a universal becomes worthy of being questioned and being seen as a threat. In the case of the Smithsonian’s exhibition of Latino art, “Latino” itself becomes a threat precisely because it is being made visible to an audience that is not particular, right? The Smithsonian’s Latino exhibition is not only for U.S. Latinos, it’s not only for the Latino artists: it is for a public U.S. audience and anyone who can actually attend the Smithsonian’s exhibition. In that moment when “Latino” is made visible (literally) through these Latino artworks, it is visualized under a rubric (Latino art) within a “universal” space (the Smithsonian). Since it hadn’t existed there before and it was not universal, “Latino” also becomes something that is not known, something that needs to be taken apart—as you said, “drilled into.” For the critic who is not familiar with this because the artwork is not addressed to him in particular, he must figure out what it is, and if he doesn’t know what it is, then he feels the need to take it apart.

Earlier you said that non-minority critics see the term “Latino” as excessive and unnecessary because Latino is too much and refers to such a broad, diverse and heterogeneous group. There is something, however, that does quote-on-quote “bring these people together,” right? As you say, for Latino artists this is not a unique experience, this is not exceptional, and it is more of the norm that Latino artists see this kind of negative response to their visibility and their art. Could you say a little more about this? What are your thoughts on how “Latino artists” or “Latino art” become useful categories in the context of the art world vis-à-vis these common experiences of rejection? In other words, if “Latino” is something that the critics, and white critics in particular, are not comfortable with, what is it about this particular term as an identity category that Latino artists find useful for them/you?

Rivera: In Kennicott’s review, the key sentence was “Latino art is a meaningless category.” Obviously, if I disagree with it, which I do, then I need to be able to explain how “Latino art” is a meaning-full category.

As I mentioned, “art” itself is a slippery word, but I think we could all agree it’s a useful one, and either way, it’s not the word that caused Kennicott’s crisis. The word that causes the crisis is “Latino.” And, being honest, “Latino” is a word that’s long been problematic for the people it claims to name. It’s a very imperfect word to describe us. But all words that name people break down at the borders. “Men” and “Women” for example. In the case of Latinos the complex history of naming us is part of what makes us, people who have roots in Latin America, or the Spanish-speaking Americas, who now live in the U.S. a fascinating story.

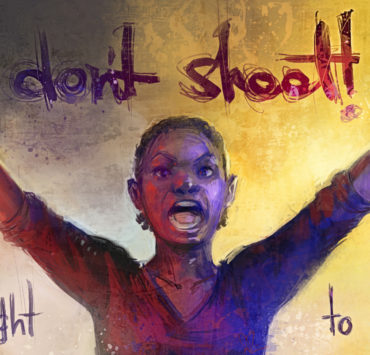

And furthermore, meaningful identity is formed not through semantics, but through the collective experience of violence. “Latino people” in America today is a meaningful concept because it refers to a group of people that is under attack. We can see our existence in statistics about unequal access to education, low income, high incarceration, disproportionate participation in the military. Latino people are currently the number one victim of hate crimes. And we also know, in the past five years, through the constantly morphing system of immigration control, that there have been over two million deportations or forced removals of primarily Latino people. So we can see that this is a grouping of people that is meaningful to look at. It’s not a random assemblage of people. We are a people who are present and fighting to be fully present. Collective violence is the forge that makes any category of people very meaningful, and it is precisely why categories like “only children” or “tall people” would make useless conceptual blocks around which to organize an exhibition of art. But “Black art,” “Women’s art,” “Latino art” are provocative and charged starting points for thinking about images because of the histories of violence in America that those groups have experienced. That’s to me what imbues the category of “Latino Art” with a powerful meaning; it’s what makes proclamations like “Latino art is a meaningless category” so wrong and reactionary.

García: Right. One of the reasons I asked you this is because I am interested in hearing your thoughts on how a term like “Latino,” or any category of identity, can be useful and productive. I think that it is precisely because of what you just said: there are certain experiences that are marginalized or conditioned through oppression in multiple and different circumstances and because of multiple different reasons. And yet, when people organize or identify based on those negative experiences—to call them “negative experiences”—people who organize or identify around them then become more of a challenge for the mainstream or the majority to understand or to address in a way that does not treat us quote-on-quote as only “a threat.” I am thinking here of José Esteban Munoz, a performance theorist that recently passed away, who was working on a book about what it means for racial, sexual and gender minorities to be and to feel like a problem: What is it like? What does it feel like to be a problem? How can people come together or organize as a result of these negative emotions? Terms like “Latinidad” and “Latino” are all-encompassing terms or categories that encompass a diverse group of people, but one of the things that does bring us together is our relationship to these negative emotions. If Latinos can come together as a group, it could be as a result of these negative emotions, because at least in theory, we all know what it’s like to feel like a problem.

In terms of Latino artists, I was really struck by your comment earlier when you said that you’re used to seeing this kind of response. If Latino artists understand the term “Latino” as something that does bind or join people together based on these negative experiences, is this a conversation that is actively happening within the Latino art community or the Latino art communities that you live among?

Rivera: Whether or not people identify and feel like it’s a useful way of seeing themselves?

García: Right. From your response I understand that that’s how you’re seeing it, but I wonder if other Latino artists are conceiving of the term “Latinidad” in similarly useful ways. The curator for the Smithsonian exhibition spent three years putting together the exhibition, and included 92 artworks by 72 artists, so obviously there is some sort of consensus among artists regarding the term. But if this is the kind of conversation that you were having with someone like Kennicott, what kind of conversations are happening among Latino artists dealing with the concept of “Latino art”?

Rivera: Well, the conversation, generally, I have a hard time speaking to, but specifically, in the world that I travel through, I am part of an association of Latino filmmakers. Do we sit around and talk about “Latinidad” or “Latino-ness” all the time? No, it’s a kind of meeting ground for us to find people that share experiences and hopes, and it’s a dynamic space, it’s a space of organizing, a piece of imagined territory that we stand on and that institutions are built on and that some power is created within by standing on that shared imaginary terrain.

García: Thank you for your response. I’m still thinking through some of the terms and ideas that came to me as I was reading these articles and the interviews. My question is in reference to a quote from your interview with Kennicott where you said: “But one strong glue that unites the community of Latino artists I know is awareness that we’re still ‘outsiders’ in spaces which claim to speak for the nation. Isn’t long-standing absence enough ‘glue’ to make this survey of Latino Art at the Smithsonian a worthy endeavor?” I don’t want to repeat the idea that Latino artists are still outsiders; the fact that it took so long to have this kind of exhibition is evidence enough of that. I would like to talk more about the different communities that you travel through. I like the idea of “traveling through communities” because it makes me think of communities as mobile and not static, they are something that is not simply “just there” and are constantly changing. In the NPR interview about “Our America,” Arlene Davila, a professor of anthropology at NYU, said the following: “I would love to be in a universe where we don’t need to have culturally specific museums because we do have a diverse museum world that represents all of us… But I don’t live in that society right now. I don’t know if we’re going to be living in that society a hundred years from now, the way we are.” If a space like the Smithsonian, or an exhibition that, as you say, were to be the territory that you’re standing on now as an artist in the art world, what is it that the Smithsonian and other spaces like it could do to become more stable for Latino artists to no longer feel as outsiders? There is the issue of incorporating and taking a serious look at Latino art and engaging with it as modern art, as American art, and as worthy of exhibitions in museums. Are there more concrete steps that you think the art world could take to make this situation not necessarily a problem?

Rivera: Personally, I don’t think Latinos and other historically excluded groups will ever find ourselves participating in a kind of uniform and peaceful representational system. I don’t think that’s possible or desirable even. I don’t think escaping “being a problem” is a goal. I think it’s important for us to say that Latinos and African Americans and Asian and Native American, the reason these categories, the reason these phrases have currency, the reason they have power, the reason that they’re useful is because America itself is a producer of those categories, that there’s a dialectical, symbiotic and inseparable connection between America as a place and the production of oppression, the production of violence, the production of race itself, and racism itself, so that, for example, the notion of “Asian” doesn’t exist until anti-immigrant laws, specifically Chinese exclusion laws, are passed in the U.S. and then the courts have to figure out “well does the Chinese Exclusion Act apply to people from India and from Japan and the Philippines?” And so then the notion of “Asia” as a kind of unity is formed here in reaction to a racist political project of exclusion, and so these identity groups that we live with today are not ways of naming people in 2014 that maybe in 2015 we will get past and maybe in 2016 we’ll get full equality. No. By talking about race and identity we’re talking about the permanent dynamic of the American imagination and it goes all the way back and must continue to go forward. These groupings of people, the way that we understand ourselves, are fundamental to the nation in which we live, and inextractable. I think that there’s always going to be a fight, it’s never done, and it’s a process of constantly grappling with history and trying to bend it, but you never break it. You never get beyond it in a full way to make progress. Can power and wealth be shared in a more equal way? Can people participate more? Can there be more mobility? Definitely yes, those are possibilities. But is a moment where this way of seeing is erased and done with? Not to me, not now, no, I don’t think so.

García: In hearing you speak, the first thing that came to my mind was the phrase “a happy multiculturalism”: all of a sudden we’re all the same, we’re all equals, therefore there is no need for difference, that difference has somehow dissuaded and everyone’s the same. And yet, as you’ve just stated, that has never been true. Creating institutions to produce an amalgamation of everything melted together and assuming that these problems are going to go away, that is not necessarily productive, right? Rather than moving away from these negative experiences by assuming that everything is the same, and that everything is happy and dandy, we ought to spend time with these difficulties to make sure that we really are addressing them. We cannot assume that they’re somehow just going to go away and that things are going to be a “happy multiculturalism.”

Earlier you said that this is the root of America and that these problems have been at the core and foundation of this country. I want to talk particularly about the moments in U.S. history where a U.S. artist has stepped onto the national stage and that people have seen it and reacted negatively to it. For example, José Feliciano, who sang the National Anthem in 1968, or more recently, Sebastien de la Cruz, the Mexican American boy who sang the National Anthem earlier this summer and sparked a massive, anti-Mexican hate movement on the internet. Events like these two are the moments when Latinos gain some sort of visibility through a medium that the public has thought of as American (i.e. the National Anthem) and a medium which everyone has an equal right to access. But, the minute something like a brown artist or a Latino artist gains the stage, this happy multiculturalism breaks down and you have this huge lash against Latinos or the Latino subject. In the case of Sebastien de la Cruz—I don’t know if you remember the case from the summer with him singing the National Anthem? [Rivera: Absolutely.]—the Mexican American boy singing the National Anthem was “too much” brownness for public television and he received a massive rejection because of his race. At this same time, when people are lashing out against the brown boy singing the National Anthem, they are also celebrating Superman in the movie Man of Steel, one of the highest grossing movies of all time. When it comes to something like Superman and the film that everyone sees, people want a “Superman” who can be an assimilated alien. As Superman says, “Dude, I’m from Kansas, I’m as American as it gets.” Everything in that movie is about the alien assimilating into America, and only then will society make him a superhero. In response to this blatant racism, the cartoonist, Lalo Alcaraz, sketched Sebastien de la Cruz singing the Anthem while wearing a mariachi outfit with an “S” on his chest. This cartoon illustrates perfectly what I’m trying to get at here: when “Latino” becomes a visible entity that is uncategorizable as something other than alien, then it becomes a problem. To me, the cartoon is suggesting ideas similar to what you are you’re saying about envisioning a future that is not resolved. The future is unresolved.

Rivera: Not post-racial.

García: Right, exactly, that you’re not moving towards a post-racial future because everything we’re seeing now is precisely the opposite. I do agree that rather than posing a perfect solution to quote on quote “the problem”—both of the white critics looking at Latinos as a problem and not knowing what to do with us, or Latinos feeling like a problem and still going on—and rather than assuming that these problems will be solved and that everything’s going to go away, we should be able to have these conversations and say “OK, this is the problem, or what we conceive is the problem, so what is going to happen here? Because the problem is not something that will simply cease to exist, that’s not going to happen.”

Rivera: Right. We are not a problem that we can be solved. We are a problem, in my opinion, that should just be understood as a process: we are in permanent process. Process. Not problem.

García: Exactly, right? Not to sound redundant, but I do have an issue with thinking of Latinos “as a problem,” and I agree that the term “issue” would probably be more relevant to use. Yet, when I read reviews like Philip Kennicott’s and discussions similar to it, it is a problem, right? It is being positioned in that way when “Latino,” as a category of Latino art, becomes a problem for the critics who don’t know what to do with it. I’m very glad to hear you say that we ought to think of it as a process.

Rivera: I think that’s right. But all of it is just drilled down into the, in terms of the specifics of what we’re talking about, look back to these reviews and the conversations about the Latino presence in these mainstream art spaces, The New York Times reviewer, Ken Johnson, when he was writing his dismissive review of “Phantom Sightings,” he cited the fact that the Whitney Biennial had almost 40% women artists that year, as a way of saying “Look, the art world is very diverse, so you don’t need to make this ‘ghettoized’ shows where you’re marking a specific space for so-called ‘minority artists,’” you don’t need those spaces because we’ve advanced and now we’re in something like a post-sexist and post-racist world, we’re there now, so you don’t need these shows. I guess what I would say is that even if magically every art exhibit was 50% men and 50% women, and it included all different races and cultures in their exact proportions, if somehow that was happening, to me these categories and the questions of race, identity, culture, and power are always going to have currency, are always going to be present, and are never going to be drained of their urgency because those conceits, those concepts, are what America is: America is that battle and that violence, and I don’t think it’s ever going to end.

García: I agree with that. I taught Sleep Dealer in my undergraduate seminar in Fall 2013, and for most (if not all) of my students, this was the first time that were faced with a film like yours—this was also the case with the sonic, visual, and literary material that I taught in my seminar. These cultural forms confronted them with the reality that this is not a peaceful post-racial society, and the reality that our society, at its core, was founded on the question of disjuncture and violence. How do we conceive of society as such and how do we live with it? For my students, to be faced with this kind of reality and these types of questions was simply mind shattering. It was very difficult for them to see the film and not feel like they were somehow being confronted. Although they didn’t necessarily feel attacked, they definitely felt more on the defensive. In discussing the film, most were defensive of the American Dream, even though my lesson plan was not intended to discuss this particular issue.

Seeing my students respond to the reality that you are envisioning—well, not necessarily envisioning it because we are living it, it’s not envisioning as much embodying it—, I saw that their difficulties with capturing and understanding this reality were not so different from the conversation about the Smithsonian. I don’t see the two as different because I see that there are parallels between my students, as members of contemporary U.S. society who are resisting or having trouble with that, and someone like Kennicott. It may not be verbalized as such, but from his review and his interviews with you and NPR, it seems to me that his resistance to understanding the significance of “Latino” is telling of his own difficulty with relating to the identities of non-white peoples. His refusal to understand your question (does he have a problem with “Latino” or “Latino art”?) stems from the fact that to do so he would have to recognize Latinidad. In order for him to first understand and then answer your question, he would have to face the legacies of violence that white critics ignore as the foundation of today’s art world. These are legacies that you are bringing to the forefront with the category of “Latino art,” and evidently they are also what the critics are leaving on the back burner.

I am not an artist and I am not part of the art world, but I am very much interested in understanding how artists conceive of reality as you describe it. Personally, learning about this exhibition and learning through different cultural forms (digital media, music, visual art, performance art) has been a complex process: I learn about them by watching and experiencing them, but I am also learning by teaching about and teaching with them. It’s been a very holistic experience for me, but it has also been very difficult for me to have that kind of conversation with people who are not used to it or that somehow see themselves as utterly unrelated to that world. In reading your exchanges with Kennicott and on Facebook, it was very interesting for me to see the kind of communities that were being formed as a result of these discussions. One of the things that I learned through the conversations regarding the exhibition, and that I am also learning in speaking with you now, is that having difficult discussions about troubling issues is emblematic of what you’re pointing to: the future cannot simply just discard that this is happening and it is our reality that requires us to communicate and to talk about what is most difficult.

Rivera: I think that that’s the great irony of Philip Kennicott’s review, and he seems to be a person with a sense of humor, he probably appreciates the irony, which is that his statement that “‘Latino art’ is a meaningless category” is absolutely disproven by the conversation that statement generates.

García: Right. Exactly!

Rivera: I mean, if it was a meaningless category, then nobody would care to talk about it, you know? But, the fact that he’s compelled to make it, and the fact that there’s clearly a ton of disagreement over it and a great curiosity to look at it, is there any other proof we need to see that the statement itself is false? This show at the Smithsonian, whether it’s a perfect show or not, whether it’s the show I would make or not, none of that is relevant, but what is very clear is that it’s like a thrust, a kind of a gesture into the void, into a space that is meaningful, that people have a stake in, and that whether it is critics that want to dismiss it, artists who are included in it and who are getting their first show on the national stage, whether it’s audiences that may go, whether it’s academics that are going to consider the debate and try to put it in a context of history, in all of these moments, in all of these myriad reactions, are exactly what a show like this should provoke, and that multiplicity of dissonant voices is what a show of American Art should produce. There’s never going to be a clear answer to the question, or a unity of voices. There needs to be multiplicities and dissonance and a battle, but that to me is the marker of some kind of success right there.

García: Right. The reaction to the phrase “it doesn’t exist” proves that it does, and it proves the fact that the statement is making itself wrong: it makes itself invalid by actually stating itself as valid. Your words are just beautiful, Alex. Yes, I get that.

Alex Rivera is a digital media artist and filmmaker. His work has won multiple awards at the Sundance Film Festival and has been screened at The Berlin International Film Festival, the Museum of Modern Art, The Guggenheim, The Getty, Lincoln Center, PBS, Telluride, and other international venues.

Armando García is Assistant Professor of Hispanic Languages and Literatures at the University of Pittsburgh. He is completing his first book, Impossible Indians: The Native Subjects of Decolonial Performance, a study of theatre, performance and the consolidation of race from the colony to the present.