In La Mucama de Omicunlé (Omikunle’s Maid) Rita Indiana Hernández approaches the epistemological marriage of knowledge and spirit through a masterful narrative that successfully mounts the reader, leading her/him back and forth through marvelous and intricate border crossings: land and sea; past, present and future; male and female bodies; animal and human world. Stylistically the novel engages Afro-futurism and science fiction while re-membering Hispaniola’s colonial and postcolonial histories. These crossings, in turn, address the most pressing concerns of our humanity—migration, racism, human rights, the environment, epidemics, violence, and the widespread proliferation of technology. In its various stylistic, linguistic, and thematic detours, La Mucama successfully locates the Dominican experience within the world.

The story of La Mucama begins in the home of Esther Escudero (also known as Omicunlé), the right-hand of and advisor to the Dominican president, in a post-apocalyptic Santo Domingo of the mid twentieth-first century. Acilde Figueroa, the main character of the novel, is Omicunlé’s maid and protégé. Prior to her hiring, Acilde prostituted herself in the Parque Mirador Sur among other pill-popping well-to-do-jaded-teenage boys “who were addicted to drugs that were still illegal” (20). Taking advantage of her androgynous look, Acilde sought out wealthy johns: “old perverts who could only get it up with teenage boys” (21). When one of her johns, a young doctor, presented her with the opportunity to work for the rich Santera, Acilde gladly accepted. The job paid well and would allow her “to save enough money to buy the injection that would complete her biological transformation into the man she always was.” Following a tragic crime in which Esther Escudero loses her life, Acilde becomes heir to her boss’s great power and riches. But with great power comes great responsibility: it will be up to Acilde to travel to the distant past and come back to the future with the answers to stop the imminent destruction of humanity: Sea levels will rise up and swallow up entire cities, strong super viruses will swallow up neighborhoods, fields will be pulverized to dust, and our world, will cease to exist. Acilde’s time travel will allow for him to go back to the origin and stop the chains of events that set off this massive destruction.

With the same rhythm, humor, irreverence, and literary mastery that made Hernández’s other novels international successes (La Estrategia de Chochueca, Papi, and Nombres y Aninmales), La Mucama emerges as a premonitory intervention that warns the reader about the undeniable and inevitable destruction of the world we live in.

But the future according to La Mucama, though not devoid of apocalyptic disasters, is also a place where humanity—in all its complexity— can regenerate as past consciousness becomes embodied through the sacred and oft-forgotten spiritual link between the corporal and the disembodied that inhabit Afro-diasporic and Native epistemes. Acilde’s rebirth into a masculine body after Omicunlé’s death is not just a triumph for Acilde. It is also a symbolic birth of hope for humanity because Acilde’s new masculine body comes to life armed with all the knowledge of the past and all the wisdom of the future. This newborn body carries the feminine and masculine forces that sustain earth. Acilde, in his rebirth, thus becomes the trans-temporal embodiment of human crossings. The narrative twists and detours that follow his rebirth also shed light on the continuous predicament of free will: the choice between individual gain and collective good.

The omniscient narrator consolidates the multiple temporal ruptures and travels that shape the lives of Acilde and other characters to send us an urgent message: “The future is coming.” In this narrative, the fantastic — time travel — mixes with the historical — violence and trauma — to produce a space where Santería becomes intertwined with immigration politics, colonialism, and the environment: “Al retirar el brillavidrios con el trapo, ve en la acera cómo un recolector caza a otro ilegal…El aparato la recoge con su brazo mecánico…Acilde no distingue a los hombres que persiguen y los aparatos amarillos parecen bulldozers en una construcción” (“After wiping off the glass with a rag, she sees how the collector hunts another illegal…The machine picks her up with its mechanical arm… Acilde cannot distinguish the other men being chased by the yellow machines that resemble construction bulldozers”) (Hernández, 12). At first glance the idea of a machine that — like a bulldozer — picks up the bodies of “illegals” off the street, as if collecting garbage, to pulverize them to nothing, seems ridiculous. Yet, the image of the bulldozer sadly resonates with the violence of anti-immigrant and racist speech that continues to dominate the public stage, evident, for instance, in Donald Trump’s campaign for the US presidency, and in the resurgence of the anti-immigrant extreme right in Europe. Hernández’s “immigrant collection” bulldozers are the embodiment of hate speech: they disappear, erase, destroy, and pulverize unwanted bodies. Hernández has been a fierce critic of Dominican anti-Haitian legislation and other forms of human discrimination. Though her work is always in dialogue with the current social and political concerns, La Mucama paints a clear yet scary picture of what will happen if we do not stop the path of dehumanization and violence.

Hernández’s work has been known for the clever rhyming of Dominican slang and musical rhythms into politically situated stories. Her voice, which is in dialogue with other contemporary Dominican writers such as Junot Díaz and Rey Andújar, is distinctly Dominican. While La Mucama retains the Dominican rhythm that characterizes Hernández’s narrative voice, particularly through location, history, and linguistic codes, it is also profoundly Caribbean and Latin American. The Latinamericanization of Hernández through La Mucama becomes palpable in the integration of vernacular slang words not typically used in the Dominican Republic and in her engagement of the fantastic (which calls to mind The Marvelous Real popularized by Carpentier). Yet, Hernández’s “fantastic” is also decidedly political in its unapologetic assertion of Afro and Indigenous epistemic — symbolized by the Being of the Sea that metamorphizes in various bodies throughout the novel and the act of bodily possession — as antidotal to the “historical truth” that perpetuates the erasure of certain bodies and certain forms of knowledge from History.

The linguistic, cultural, and historical translations of Dominicanidad into a wider Latin American vernacular open Hernández’s work to a larger readership, particularly to the urban youth, the politically minded, and the aesthetically daring. Though I have been a big fan of Rita Indiana since the beginning of her brilliant career, La Mucama, even more so than her previous texts, has made me a true convert. I am possessed, bewitched and bewildered by this novel. If you are brave, if you dare, you should read it too.

Buy the book La Mucama de Omicuni

by Rita Indiana Hernández. Spanish. Periférica, Spain, 2015.

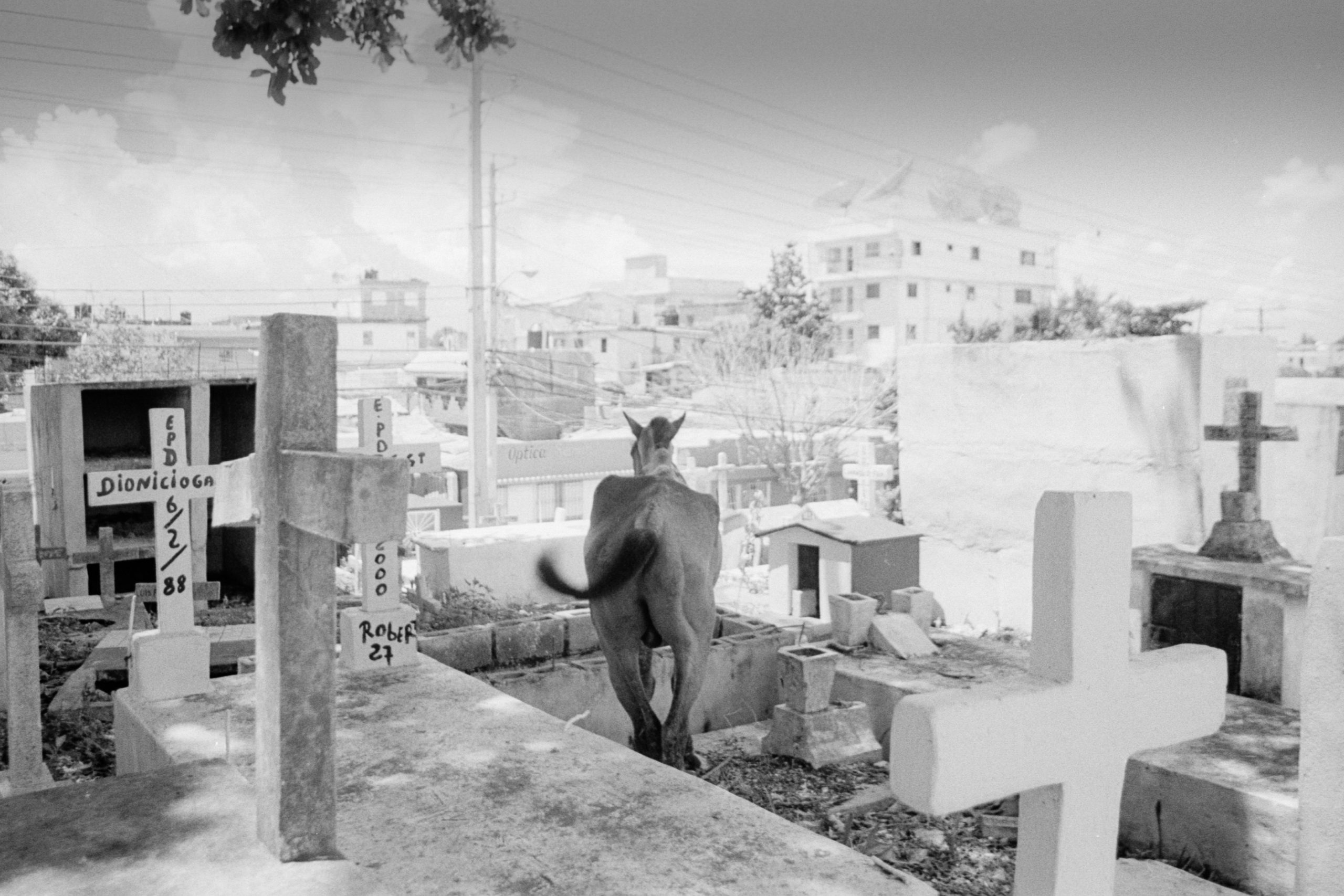

Image Credits: John Gallagher

For more on John Gallagher’s work visit his website.

Lorgia García-Peña is a Professor of Latinx Studies at Tufts University, the co-founder of Freedom University Georgia, and the author of three books: Translating Blackness (2022), Community as Rebellion (2022) and The Borders of Dominicanidad (Duke 2016). She is the co-editor of the Texas University Press series, Latinx: the Future is now and the co-director of Archives of Justice. She writes and teaches in English and Spanish about the intersections of blackness, colonialism and migration, centering Black Latinx lives.