Let’s have a drink by the pool, ladies.

Act One: Preface, The City

This small post-industrial American city is block by block of beer, sports stadiums, and the grunt and sacrifice of workers. Each enclave of the city reveals itself only slightly when pressed against. Deceptive wooden door heavy and creaking; palms of strange hands flat firm against its metal plate, a darkened room. Lining the entire right wall of the room a long mahogany bar; behind the bar its keeper, casually awaiting a customer (In this version, the sun has not yet gone down, though it is cloudy; the workers have not yet been released.). In the corner of the darkened room, a television; on the television, a game or a race or a match. Draft beer pulleys abound, about 20 of them and as many makes in bottles. There are three kinds of vodka and I am grateful for the choice.

As a martini drinker in the post-industrial city, I’ve become peculiar and picky, some might say an annoying snob, others might say a pretentious grump. To my own defense, it’s not as if the things I desire to make my life a little more satisfactory are of an other worldly order. A barroom sans oppressive artificial light. A group of close friends who all share a biting ironic sense of humor; the exhilaration of making art; and a perfectly prepared, transformative martini. Since encountering the post-industrial city, I’ve left those friends in my last city and find myself a fish amongst the earnest. I’m often forced by profession or social engagement to endure a room swathed in throat-cutting brightness (and not from a window). And, on the days I am lucky enough to peel my head up from the concrete floor of ennui, I am usually not lucky enough to write any poetry, or make any art, but instead muddle around waiting for summer when everything including my heart convexes and gets gleaming again. In short, I put a lot eggs in that martini basket, so when the martini arrives grey with too much olive brine, or coppery from too much vermouth, or God forbid, lukewarm, I send it back. If the martini is wrong, everything is wrong.

I prefer vodka martinis to gin and like them served “up” when the liquor kisses the lip of the glass and I must kiss the lip of the glass and sip before any attempt at transporting it. There’s nothing practical about the martini. Instead, the martini is an exemplar of excess, what you surely don’t need but luxuriate in anyway. You can’t drink martinis all night, or you’re drunk before dinner and massaging the knee of the person sitting adjacent you, not your lover, who’s, of course, on your other side. A martini requires a thing I do not have—restraint—but I love them anyway. A martini “up” must be served in a special glass shaped like an upside down triangle, what might be called a “V”; even if the glass is not rim-full, walking with a martini is not easy. One cannot gesture wildly while talking. The body must be held a little tighter, which is why I suspect New Englanders, or at least people from upper crust Connecticut as I imagine them, have a preference for martinis as they reinforce an already ingrained social code of the body. One is required to take measured steps and pull the elbow in toward the body in the martini holding so that the arm, if moving, is anchored by the elbow/side-of-body connection. Martinis can femme up the butchest girl and make the most macho guy appear a tad fey. The martini, in other words, is intentional, transformational. You think you’re in control of it, but really, the martini is a disciplinary apparatus, dictating not only the body’s movements, but inescapably one’s sense of one’s self before the first sip is taken, and the nature of one’s awareness following. Martinis train the body. It’s normative “effects” or whatever are disrupted in the holding of the glass, the sip-long break-sip agreement, the good-taste-ness of the whole performative affair. Without much effort, then, the martini can pull us, however briefly, from our burdened class roots. Unless you’re doing it all wrong (chugging falls into this category, so does abundant spilling), the body is immediately trained toward some other “higher” articulation of the body.

I’ll say now that I mention the post-industrial city, the stadiums, the beer, because as fate would have it, I’ve ended up living (temporarily at the very least) in a city that is everything I’ve been running away from—desperate red-eyed bodies on street corners, sharp I-fucking-dare-you-to-look-this-way stares into passing car windows, fragile souls breaking inside themselves and over others, and a casual “it is what it is-ness” to the seemingly timeless package. To be fair, this post-industrial city, the one I live in now, has a striking beauty to it. One approaches town from the airport via a tunnel carved through what I assume to be a mountain. Here the city announces both a confident yearning and a John Carver-y sense of possibility. We do not, as one might expect, imagine the dim smooshed cries of newly pierced virgins or the wet dreams of young sailors, but the thing itself, the shimmering city suddenly open to us with fountains and history, rivers and promise, the color of activity, and bend after bend of bridges from one thing to the other. The city wants something; it desires, and reaches for another life. What the city lacks now, perhaps, is embodied in the martini—a contrived sophistication so entirely altering, one can rethink the self. The martini does not want. The martini simply is.

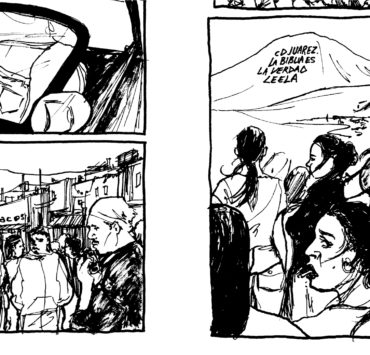

Act Two: A Visit “Home”

If there are ghosts, and there are, they do not present themselves, but instead linger within white walls, blending, so that the haunted is uncertain about their presence. On the burgundy leather sofa in my mother’s living room, a flash of an imagined child me swinging on the living room door as if flying; a scent memory, unpleasant and grimy; a rapid series of images, each as still as death. I have arrived five hours late for a 48-hour visit after having driven on a wildly detouring route, lingering at a shopping mall, and purchasing a pint of Absolute vodka and a small jar of Spanish olives. When I finally arrive my mother and I fall into our usual dynamic. We are stereotypes. We wrestle with one another in one of those typically fraught mother-daughter relationships; it seems beyond us, and yet, is us in action and only us. My mother insists on thing after thing, idea after idea, and I attempt to resist my usual trajectory in which I devolve into a person locked inside of a precise, haunting, tangible anger. Resistance, in this instance, looks a lot like the thing itself. When one clinches the jaw in resistance, the jaw is clinched, isn’t it? In a blue plastic cup, then, I mix a secret dirty martini, so dry the vermouth is still at the liquor store on a dusty shelf.

I should say here that the problem is not my mother, who is elderly or almost elderly now (I noticed on this trip with an intake of breath that the shape of my mother’s mouth in relation to her teeth is changing. I’ve seen this exact alteration of features on other older people, most prominently on my father, whose two-year-long death from a cancer of the blood aged him rapidly and dramatically, so that as he lay in the hospital bed on the last day I saw him alive, he seemed like someone flaccid and adrift, perhaps related to a person I once knew.) My mother and I, after all, love each other. My anger, then, while sometimes misdirected at my mother or the house or my deadbeat dad jobless 25-year-old cousin who happens to currently live with my mother, is really about the “situation.” My therapist would call my stealthy martini, “self-medication,” but that’s only because she relies on the pre-packaged language of psychoanalysis to describe everything. The musical group Bright Eyes says into my headphones, “Let the poets cry themselves to sleep,” and there is a bit of that too this night, but also this saving grace, as when you discover that the green algae that is the essential element of your diet is also a medicinal herb that clears the head and lets one descend back into the lost body.

A light-year is a unit of distance. How far away are the stars? How far away is the next galaxy? A single light-year is equal to approximately 5,878,630,000,000 miles. I am a light-year away, a light-year in time and space in another galaxy. Drama of the room, its 50 foot ceilings, draped in translucent Egyptian white scrim, its massive white columns, and white upholstered sofas, subtle lighting, a prominent twinkling Walk out to the infinity swimming pool, pool beds and canopies, swaying palm trees, lush tropical gardens. My martini tonight is a cosmopolitan, flecks of ice float on the surface. I take a long sip. My girlfriends and I have come because spring is near but winter in the northeast still has its brutal grip. We have come to fill out bodies with sunlight and awe. Bottle service is encouraged, but we sink into the beds with our feet resting on the pool’s edge, and order one cocktail and then another. Suddenly, we are these women, away in early March basking in the forever Miami sun, and everything is possible.

In my mother’s view a good Christian does not drink (I am actually not a Christian, not religious at all, but that doesn’t discourage in the least this line of reasoning). Anything other than “a swallow” is ungodly, sinful, ugly. A good Christian woman takes care of others instead of herself. If one is bending over from firewater, one is much less likely to bake a ham. My father, in contrast to my mother, drank, and did so, I believe, to survive. Until he retired at whatever age, he worked two full-time jobs. That means that Monday through Friday he worked a 7-3 shift and a 4-midnight shift, arriving home long after we were all securely tucked in, well-fed, warm, and rubbing our sleeping bellies, to eat his dinner, which was stagnant and heat-congealed in the oven, alone at the dining room table. Sometimes I would find him there in the half glow from the kitchen, in the near dark, eating quietly, the clack clack of the fork against the plate and a mouth full of false teeth, and wonder how any of this was possible.

Although the house itself haunts, the neighborhood of my childhood is one that feels almost entirely foreign to me now. When I visit these days, when the weather is nice, I bring my bike along and ride around the places where I rode my bike as a kid: the high school, the mini strip mall, the corner candy store, another mini strip mall. None of it seems familiar; no sentiment or nostalgia nudges into me. I have the memory of being here, but it’s as if through a jar, all the edges rounded, the events themselves obscured and strange. My mother tells me of a cousin here who although 46 and able-bodied and male, “does nothing,” another who is recently released from prison, another who is “crazy.” What’s wrong with the crazy one,” I ask. “I don’t know,” she says. “Does her mother know?” I ask. “I’ve never asked her,” says my mother. My mother’s good friend, whom I remember vaguely from childhood as being “scary,” has a son in his forties who let the symptoms of diabetes turn into gangrene and had to have his leg cut off below the knee. He’s on disability so also “does nothing.” “Maybe he wanted to die,” I say. When I say this, I might as well be holding a second blue plastic martini. I believe I, in fact, am. I wonder how this neighborhood, which seemed safe and “normal” to me when I was a kid, could produce such heartbreaking misfits. I’ll tell you a secret. I’m afraid that I’ll be left to occupy in a more prolonged sense this hole that fragmentation has dug, this operation on site with rusted tools, that one day, perhaps, I won’t be spending a Saturday afternoon after on a blanket in Central Park reading The Times or at the Waldorf Astoria’s Bull and Bear, smoking a cigar (it used to be a cigar bar, but now it’s a steakhouse) and having a single massive $25 martini with my girlfriends but instead “doing nothing” in a manner where a leg is disposed of in a medical waste bucket.

Act Three: The Most Popular Girl in School

Careful, my plastic martini whispers in my ear, you don’t want to become a bitter woman. There’s nothing less pretty than a bitter woman. I take another sip, nodding silently. This is not what I meant, I want to tell the martini. This is not the story I want to write. The martini shakes its head, disparagingly. If I weren’t writing about drinking martinis, I say back, I’d be drinking scotch right now, the strong silent type, instead of being forced to endure the whip of your sarcasm. My martini performs a gesture that’s akin to rolling its eyes; I guess I should say, it turns its olives. Whatever, it mumbles. I get the sense it has a certain distain for me, a looking down the long stem of its nose, shall we say. But I don’t care. I realize that the martini is the celebrity. I’m the star-fucker. I’ll ride sidecar, do all the behind the scenes grunt work, what have you. The martini as a companion is an untrustworthy one, but I’ll take the risk.

I am sitting in a red restaurant in Northampton, Massachusetts with a date-ish. We’re both drinking martinis. When the conversation stalls, I glimpse a face I think I know at another table. She sees me, recognizes me and, poof, she is at our table—the iconic Most-Popular-Girl, or “MPG,” from high school. I’ll call her M. M was a virgin and a bad girl, a Christian yet depraved, cute but not gorgeous. She achieved mythic status, however, only after our sophomore year when her parents sent her to a high school for mentally ill youth. Being gone and “crazy” made us worship her more. I hadn’t seen her since we all got word of her institutionalization, but there she was, right in front of me like the second coming of Christ. A miracle. I gasped. M here in the flesh, sipping, I noticed, white wine in the dead of winter like a dodo. I hold my little celebrity in my right hand, take a sip, chatting casually when M says, “I don’t remember you being so sophisticated.” “That was a long time ago, wasn’t it?” I say. I remember now that I was wearing Emporio Armani tuxedo pants (bought for 80% off, but who cares?!) and a black t-shirt, but it was the martini that winked (as it is wont to do) and sparkled like a time before our time, a certain, yes MPG M, sophistication.

As a class-climber raised in the maw of urban decay (see Act Two), the martini adds to my cache, helps me build my cult of personality and beat back the crunching persistence of past, other, lives (see Act’s One and Two). I suppose my love of the martini occurred by happenstance, that I simply stumbled upon the martini during my first graduate school stint, muttered, “hello, old friend,” and off we were on a wild excursion together. Escaping the network of constructed blacknesses projected into the consciousnesses of the American populous writ large is not really possible, but one I can pretend, can’t I? I couldn’t recall then, and can’t even now, a single Hollywood movie in which a black person is drinking a martini. I do not mean to contend that there are no popular cultural productions in which a black person is drinking a martini as there most likely are. If, however, the Family Feud category is “alcoholic drinks black people drink,” the martini is surely low on the list. The closest the viewer gets in the black and white films of the 1930s, when martinis are the height of cool and worldly wisdom, is a tuxedoed black hand reaching in to serve it.

Despite M MPG’s youth crises and subsequent stint at the school/hospital, I would never have imagined a burnt out fire years later when we’re both adults. The day of our happenstance encounter, I saw a vacancy behind the eyes, a thoughtful no place or every place, I’m not sure. Whatever it was, the gaze didn’t catch me in its hold like it used to for all of us who were wrapped up into her experience. Maybe I didn’t need her as much. After all, I had my martini. M and I were friends, I guess, though at the time she seemed more akin to what my martini is now, a celebrity who let me hang around. M sent me one letter from the hospital/school shortly after her arrival. It was rubber stamped several times, as if in a fever, with a mad hair-shocked face. They can’t bring this girl down, I’m sure I thought, she’s laughing all the way to Saint-Tropez.

Act Four: Epilogue

The martini—more its symbolism of carefree privilege than its potent delivery of intoxication— helps me write my way out of one story and into the one I imagined for M all those years ago. Is the martini really transformative? Beyond its ability to get one really drunk, probably not. It belies a certain awareness and even though it can discipline the body, that discipline if defining in the moment is temporary, fleeting. The body gets soft, the martini spills anyway, and all self-discipline goes out the window (see the moment in Act One re: “massaging the knee of the person sitting adjacent you”). We cannot, then, rely on the martini in actuality as an agent in our own transformation. But symbolically, the martini offers us something on the other side of yearning, access to an interiority free from impurities and defiantly ourselves. Enter the dead. They bang noisily on a glass partition. I stare at them, then turn my back to the glass.

In the post-industrial city, secluded away from the twittering hubbub of the university, vaguely lulled by the hum of a sports’ announcer, and in the relative quiet of a cave-like bar, as I resist most of my tendencies toward snobbery and simply choose a vodka for my martini, Stolichnaya, I feel a bit like the only survivor of a smoking train wreck. Strangely upright, I brush of my soot-drenched clothes, look around, saying out loud in a panicked voice to no one, Damn, I’m lucky. It happens that I’m standing dangerously close to the train, not moving or feeling threatened, and that we’re in the middle of a ghostly nowhere, no house or road within eye’s reach, and I seem to have misplaced my cell phone. In my right hand is a broken martini glass, but a big sip miraculously remains at the bottom with one fat olive and somehow I can’t resist drinking it, glass fragments be damned. Here’s to everything! I toast. The bartender got it just right.

Originally published in, Make Mine a Double: Why Women Like Us Like to Drink, edited by Regina Barreca

Andrew Kenower Poet and activist Dawn Lundy Martin earned a BA at the University of Connecticut, an MA at San Francisco State University, and a PhD at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her poetry collections include Discipline (2011), chosen by Fanny Howe for the Nightboat Books Prize, and A Gathering of Matter/A Matter of Gathering (2007), which was selected for the Cave Canem Poetry Prize by Carl Phillips and was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award. Precise, tender, and unflinching, Martin’s work is at once innovative and emotionally fraught. Fanny Howe described the poems in Discipline as “dense and deep. They are necessary, and hot on the eye.” With Vivien Labaton, Martin coedited The Fire This Time: Young Activists and the New Feminism (2004). She also cofounded both the Third Wave Foundation and the post-theorist Black Took Collective. She has received the Academy of American Arts and Science’s May Sarton Prize for Poetry as well as grants from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Martin has taught at the University of Pittsburgh, The New School, and Bard College.