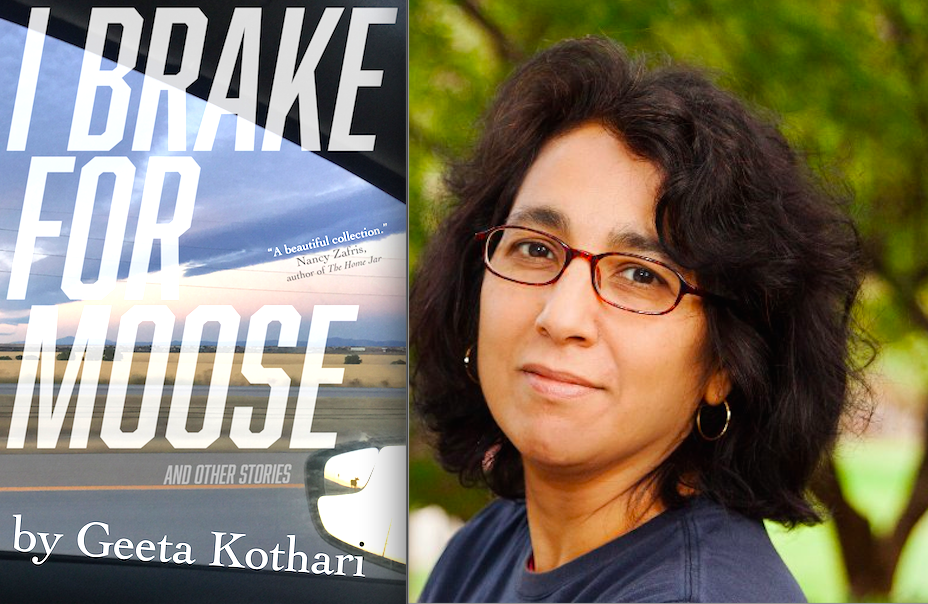

As part of the Aster(ix) in Alphabet City Series for City of Asylum Clarissa León spoke to Geeta Kothari about her writing process, her relationship with her late mother, and the things she left behind

CL: It’s been about several years – almost two decades – since you last published a book like I Brake for Moose. How do you feel the length of time has affected your work?

GK: I think over time my terrain developed. There’s a sense of estrangement and alienation in the stories. And that developed organically over time. I do think that time helped me mine various aspects of my life that sort of blend into the stories without any real consciousness on my part, in the sense of ‘Oh, I’m going to write another story about someone who’s at odds with their landscape or who feels out of place or like a misfit.’ When I put the collection together there were things I noticed that some of the stories had in common. I noticed there were a lot of cars in my stories and a lot of people moving, and I think that speaks to my own inner restlessness or sense of dislocation or not feeling attached to a particular landscape.

CL: How has your process of writing changed over time?

GK: My process changed a lot over time. The major turning point was when I went to the Kenyon Review Writer’s Workshop for the first time. We had to write fast. We had to write to prompts. We had to turn around stories in a day. That first workshop taught me a lot about structure, looking for structures, and then writing into a structure. I’m not great at seeing those structures, but when I do see one, it is really helpful to me and it allows me to write more efficiently.

CL: I’m going to go and switch a little bit. I heard once that you wanted to be a flight attendant? What exactly happened there, because it’s a little far off from the goal of becoming a writer? In “Flight Attendants Take Your Seat” you write about a flight attendant in training with motion sickness. Was that any way of referring to your own relationship of having this goal but never attaining it?

GK: I did want to be a flight attendant. It was definitely a goal in my life. I switched gears when a friend said to me, “You know you are essentially going to be a waitress in the air getting your ass pinched and having people throw up on you.” And that kind of put it into perspective. How it relates to writing is again, this theme of people in transit that runs through the collection. In “Flight Attendants Take Your Seat,” I see that character as someone who desperately wants to do something else with his life, but doesn’t quite know what that is. And I think that’s the same in “I Brake for Moose,” and I felt like I was those people at some point, between wanting to become a flight attendant and then eventually becoming something else.

CL: You’ve said before that you’ve felt lost before, without any sure place of where you’re from. Why do you feel that you don’t have that?

GK: I felt like I was from many places but no place in particular. I grew up in New York City. My parents were from India. We spent a lot of time in India when I was growing up and my parents were very ambivalent about their immigration status. My mother didn’t see herself as an immigrant at all. They wanted us to get the best out of being in the United States but they also didn’t want us to be American. To be American was to be unambitious, too fun loving, not very bright. At least that’s the impression my sister and I had. In the year I was born there were about 4,000 people of Indian or Pakistani descent in the Tri-State area. Those census numbers worked against us. This was probably Trump’s idea of the Golden Age, right before immigration laws changed and increased the quota from South Asian countries. When I went to India I felt at home with my family, but I was very much aware that I wasn’t from India, and in New York I always felt like we were there temporarily — that at any moment we could be leaving.

CL: With some of the women characters in your pieces, it’s stories of love and lack of affection from someone or something they can’t get. It’s interesting how you decide to write the opposite of an assimilation story, and in many ways you, and your characters, are placed outside of that storyline.

GK: My earliest role model was someone who was not ever going to assimilate. She saw herself as someone who came here to work. She was on a G-4 visa for much of her life. That’s a visa that needs to be renewed every year, and is completely dependent on your employment. My mother never felt assimilated. She resisted it. I can see why she saw herself in this temporary status. She worked at the United Nations, which is on international territory in the middle of New York. So, symbolically everything was working against assimilation. She wore her sari to work every single day, and she herself said she felt if she hadn’t worn a sari she might have gotten further within the U.N. I asked her once, “Why don’t you ever wear a dress?” when I was a kid. She said, “I’m Indian. I work at the U.N. and I represent my country so I wear my sari.” But there was this very keen awareness that wearing her sari also placed her outside the power structure in some way. So my characters find their seeds in her, I guess. They just can’t assimilate. People just learn to live with their outsiderness. They adapt to that rather than the larger culture. There’s no clean, neat resolution.

CL: I think one of the things I thought about while reading your work is that there’s an intimacy to your stories. The idea of immigrants and that story is not out there enough – and the variety of those stories, as well. But we don’t really get to hear stories like those as often.

GK: We need to reclaim those narratives. I mean, really make them part of the main narrative. Currently we’re drowning in anti-immigrant rhetoric. It’s a backlash for sure. And it’s so misplaced. It’s just crazy. Any story that puts the reader into someone else’s shoes is an antidote—or maybe armor.

CL: You’ve said earlier, there’s nothing you can change about the place you come from and the parents you have, but it’s also difficult to change perspective on people’s own views of where you’re from and how you grew up.

GK: Yeah, they still see you as someone from somewhere else. My first published essay was about being constantly asked where I’m from, and I don’t mind the question in conversation with someone, a real back and forth exchange. What I object to is someone randomly at the bus stop asking me where I’m from. When I was younger I was very uncomfortable with that kind of intrusiveness, and now I’ve made my peace with the discomfort. In the sense that, once you pass 40 I think a lot of things that bothered you when you were younger just no longer do. They eat at you differently, but I don’t feel this defensive armor all the time when I go out in the world. I’ve become much more observant and less likely to take the blame for situations. And I think part of it is when both my parents died in the same year, I understood that time is something I’m not going to get back.

CL: You’ve also mentioned at the City of Asylum reading that your mother did not want you writing about her while she was alive. How has that changed now that she’s died, and do you feel differently toward her or her story or your writing her story?

GK: She very much did not want me to write about her after she was gone. But she also was incredibly interesting to me. So was my father. But they were very private people. And when she died it was really quite unbelievable to me that she could be gone and I could still be here. I just really had a hard time understanding how that was possible. When I first started writing about her it was just as a way for me to feel closer to her and bring back the best of her. Then, as I got deeper and deeper into it, of course, the best of her also comes with the worst of her. So you can’t write about one without the other.

Eventually, I became more interested in why she stayed in this country. She came here and she had 10 years within which to return to India. She wasn’t married, she didn’t have children and then she met my father in New York and they married and they had us. And I wanted to know more about the attempts they made to return, and why they ultimately stayed here. To me it’s a much bigger story about home. She had opportunities to go home and chose not to take them for what reasons. That became very important to me to figure out.

CL: Does she write with you when you’re writing? Or do you know what she would say about what you are showing me?

GK: She left me a lot of notes and poems. I guess she knew I was going to write this before long before she died. I also interviewed her (and my father) because when I left New York and moved here, I realized how little I knew about them. And I thought they’re not going to be around one day. I need to pay attention. So I think in that sense she’s with me. I don’t think she would totally disapprove of what I’m doing. I think she might disagree with some of my conclusions. She did disagree with things I wrote, and that was her whole thing — she didn’t want me writing about her when she couldn’t respond. She would have been fine with the book if she could have responded to everything. Some of her friends who are still alive might have problems with the book for the same reason, because my conclusions are all through the lens of who I am both as her daughter and as a writer, and that is naturally going to be different from how they see her or her self-evaluation. But she left me drawings, she left me maps, and I take them out and I look at them and they’re lovely. Some of them are fading because I’ve had them so long. When she first died I felt like ‘Oh my God, she left me nothing.’ But then I started to look through all my stuff and she left quite a bit.

CL: How did you parents take you becoming a writer? Did they push you in any other direction?

GK: As immigrant parents, they were oddly uninvested in that particular conversation. And I’m not sure why because they definitely wanted me to make money. They kept saying, “You need to have a career, you need to focus.” But there was no pushing me towards a particular career, and I think part of it was they had no clue what to push me towards. My mom had been at the U.N. since she was 22. She’d been at the same job forever. My dad was a doctor. He knew I didn’t want to be a doctor, but there was no suggestion that I might go into another specific professional field, like pharmacy or engineering. And I don’t know why. That’s just who they were. My sister and I’ve had long conversations about this she majored in religion and studied photography, and I majored in Government (Poli Sci as it was called at my school) and Afro-American studies and then I got a degree in writing.

CL: Do you appreciate all that now?

GK: I do. I didn’t get it earlier. It wasn’t that they didn’t worry about where my money was going to come from or how I was going to make money. Maybe they thought I was just going to write a bestseller. I have no idea. Maybe if they’ve been around a lot of other high-achieving Indian parents, driving their kids into med school, they might have felt competitive and pushed us in a certain direction.

CL: In terms of writing structure, you’ve decided to focus on three different strands to this book. Can you talk a little bit about what that structure looks like and how you decided on the different strands?

GK: After assembling all the notes and research in Scrivener, I wrote a first draft that was structured thematically. But because there is so much historical detail and information most readers will be unfamiliar with, I had to restructure the whole book. So the three strands are my mother’s life, which provides the main chronology, and then there’s the second main strand of what happened in 2004 when she died while visiting family, and I went back to India to help my father. Then, the third strand, which bridges the two main ones, is not chronological, where I consider our lives together, as a family. At first it felt very mechanical, but it’s helped me tame all the material and create a narrative that makes sense. I would have liked to have had written something experimental and crazy, because I read those books and I love them. But I need a clear understanding of structure when I write, and that’s something about myself that I’ve had to accept.

CL: Do you think stories like hers are important for you or for the literary landscape? We don’t necessarily see those characters in the mainstream, but there has been a big push to see more characters like hers. In several of your pieces in I Brake for Moose, you have characters from different countries, Africa for one.

GK: I’m not looking to create situations where I need to create a specific type of character to enable plot, but I am interested in a broad range of experiences. The character in “Missing Men” emerged as African somewhat organically, and I would say that about all the characters — it wasn’t deliberate on my part, but comes from where I grew up, in a kind of utopia for multiculturalism. My best friends childhood friends were African and Nepali. This upbringing naturally informs the way I look at things. I felt for a long time I had to apologize for not writing a book in which all the characters were Indian. That this was my ethnic slot and I have to live in it. I can’t apologize for not fitting into some marketing category. That’s not really my problem. That’s a marketing problem. That’s not a writerly problem. I’m writing the stories that I feel are important and I hope I’m not doing damage in representing those characters. I don’t try to pass myself off as someone who knows more than they do. I don’t feel I engage in stereotypes.

CL: Are you finding more stories like that where stories have more of these cheap, not organic characters?

GK: No, but that might also be indicative of my reading. I’m not reading a lot of mainstream writers. I read a lot of small press books. But this is largely a question of craft, isn’t it? When a character is tacked on for the sake of plot or to make a political statement, readers know. Questions that take the reader outside the story, i.e. questions of authenticity, reveal the faultline. You asked do I feel my mother’s story needs to be out there. I’m not thinking about it that way yet, but that’s never been the drive to write this book. I wrote it primarily for myself or my niece and my nephew. I want them to know where they came from, and for future generations I want them to know how we all ended up here.

CL: Can you speak a little about the process of writing and research for your upcoming book about your mother?

GK: Right after she died I started taking notes, but I wasn’t thinking about a book. The more people I talked to, however, the more they would say, “Well that’s really kind of amazing and insane.” How many Indian women of her age in 1950 got on a plane and went somewhere by themselves? And the thing that really hit me was when I was in India at one point and I was telling this young woman about her, and she said, “It couldn’t have been that big a deal. She had her husband.” She was so offhand, and I thought well, this is another assumption I have to correct, that coming to the United States in 1950 was easy — for anyone — but particularly for a woman wearing a sari. No, not so easy.

CL:Do you make any types of distinction between your fiction and nonfiction works? I know several authors use the time to experiment.

GK: Someone asked me why so many of the stories in the collection were in third person. And I think that’s one distinction — I really like writing in the third person. I would like to really explore different perspectives, and fiction offers me that chance to inhabit different lives. In nonfiction, I address directly my autobiographical material. That’s why you won’t find me writing thinly disguised autobiographical stories or some kind of hybrid. Once I’ve taken care of those stories in nonfiction, they no longer intrude on the fiction.

CL: Well, do you think there are also similarities between your fiction and nonfiction? Can you tell me a little bit more about that and how you can decide between the two?

GK: Common details and themes surface, but the plotlines and stories usually quite different. For example, the suitcase in “Small Bang Only” is one my mother acquired when she first came to the U.N. In nonfiction, I’d probably use that suitcase to launch a larger inquiry into the U.N. and my mother’s early days there. In the story, it’s a small, specific detail.

What I love about fiction is being able to enter other people’s lives. It’s really so freeing for me. After I’ve finished this book about my mother I will probably go on a long jag of writing fiction just to not be inside my life. It can become quite suffocating.

CL: In relation to fiction bringing readers an experience, what is the experience you wanted readers to have while reading I Brake for Moose?

GK: I would like readers to immerse themselves in other lives. That is more important now than ever before. There seems an urgency to that.

CL: Do you think a lot more about that now given the situation we’re in right now? And how so?

GK: The stunning lack of empathy that you see on a daily basis and the lack of historical knowledge is disturbing. It is just amazing to me that in this age of global communication of more information than ever before, that we should have people who are doggedly unempathetic and doggedly uninterested in other people. I just don’t get that. To me the most interesting thing is someone else and their experience.

CL: I have to ask this. When we were at the City of Asylum Sampsonia reading, you got a question from the audience about flowers. Somebody asked “What is your favorite flower?” and you responded that you didn’t know, but you really didn’t like irises. I couldn’t really find the answer to why that was.

GK: We actually have a lot of irises in our yard and I like them outdoors, which is where I think they belong. I specifically do not like purple irises. They remind of someone I’d rather forget.

CL: Oh, ok!

GK: It’s no big mystery. It just came out at the reading, but my husband was in the audience and he was a little stunned. He thought I was making things up.

CL:Oh really. He hadn’t known?

GK: He hadn’t paid attention when I said it before. So now he knows. It’s on the record, and it’s going in this interview.

CL: Is there anything else that is on your mind?

GK: I’d like to apologize to irises.

Geeta Kothari, is the nonfiction editor of the Kenyon Review, a two-time recipient of the fellowship in literature from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and a senior lecturer at the University of Pittsburgh. Her latest book of fiction, I Brake for Moose and Other Stories was published this February by Braddock Avenue Books. She’s currently working on a nonfiction book about her mother’s life and death, where she writes about themes of tradition, mothers and daughters, assimilation, and feeling like an outsider without a home.

Buy I Brake for Moose and Other Stories by Geeta Kothari

Clarissa A. León is the Managing Editor for Aster(ix) Journal.