Dime con quién andas y te diré quién eres

Part I

1

Conciencia was born with the map of Puerto Rico on her thigh. The main island and the neighboring small islands of Vieques, Culebra, Desecheo, Mona, Caja de Muertos and over a hundred even smaller islands, islets and cays took the shape of white vitiligo spots on Conciencia’s dark brown skin. Her skin glistened as if she had bathed in a tub of liquid gold. When she gets older, her high cheekbones will give off a bloody red glow. One of her almond shaped eyes had white eyelashes that when she blinked it looked like tiny butterflies were sprinting on her face.

2

Doña Nina got into the foster care system because she cared about children. When Conciencia was presented to her, she knew that she would love this seven-year-old child who looked like she could be her own child.

Things were different in this home. Conciencia did not slam doors or kick chairs. The first day she was sent to live with Doña Nina, she made Conciencia guava empanadas. She looked at the empanadas then at Doña Nina.

“Come, niña. I made them for you.”

Conciencia was hungry and bit into the warm and gooey guava. Mmmmmmm. She had never tasted something so good. Her tummy was filled. Doña Nina gave her another and another until Conciencia fell asleep with her head folded on the table.

Doña Nina may have been overweight, diabetic and had a compromised heart, but she was strong enough to carry Conciencia’s eighty-pound body to the twin bed she had bought just for her. She wiped the guava gel from Conciencia’s cheeks and blessed her before going into her room and praying to the many saints she worshiped.

Conciencia’s hair had been cut to the scalp, like a boy’s buzz cut. The six children in the foster home had gotten lice and cutting their hair was an expected course of action. But even before the lice, Conciencia’s hair had been cut short. Conciencia didn’t like combing her hair and fought when anyone else tried doing so. No one knew how to unknot her hair. But things were different in this new home. Doña Nina boiled onions and used the onion water with coconut oil to massage Conciencia’s scalp. After two months Conciencia’s thick strong black hair began to grow. Doña Nina taught Conciencia to untangle her hair with her fingers while she was in the bath. Every week she deep conditioned it with mayonnaise and eggs. No longer did Conciencia have to feel the knuckles of someone frustrated with Conciencia’s ouch and aii. When Conciencia’s hair was long enough, Doña Nina taught her how to braid her own hair. Conciencia loved this look the most. For the first time ever, at the age of eleven, she looked in the mirror and saw someone pretty. By the time she was twelve, she wore her hair in two thick braids that made her stand out from everyone in the crowd.

Doña Nina taught her how to cook, how to make the masa for the empanadas. Soon they were making a business out of their home, selling empanadas de queso, de pollo, y de guava y queso. They sold them three for one dollar. Conciencia would do everything to create the masa, made of flour, butter, water and her secret ingredient, brown sugar. She shaped them like a pregnant belly and gave them their forked ridges. Doña Nina would fry them because she did not think Conciencia understood the danger of fire.

Conciencia finally had someone she could call Mamá. Someone with large bosoms to lean against. Someone to bring slippers to. Someone who didn’t have a large voice, instead she said Conciencia’s name the way it was meant to be said, like gentle waves coming from her mouth with a sweetness like her guava empanadas.

One night Doña Nina woke up screaming, “No! No!” and ran to Conciencia’s room and they both knelt down while Doña Nina prayed in a way that Conciencia couldn’t understand. She wasn’t even really praying. She was begging. When Conciencia asked her what was wrong, she shook her head, “pray with me, pray.”

Doña Nina didn’t want her to know that she had dreamt that she carried Conciencia’s infant body to the third-floor window and accidentally dropped her three flights down. She woke up begging, “God no!”

Two days later when Conciencia had just finished eating her oatmeal before going to school, Doña Nina smiled fully and told her, “You’re going to be okay. Last night I dreamt that you were riding the white horse of Santa Barbara. You’ll be okay. There will be forces that will try to destroy you because you are going to be very powerful, but do not worry, Yemaya and Santa Barbara will protect you. Pray to them. Que bueno que Santa Barbara te escogió a ti como soldada fiel. Santa Barbara has chosen you to be one of her trusted soldiers.

3

Conciencia was put into special education classes just a few months into first grade. She was placed in a room with children that threw chairs against walls and favored the word fuck over all other words. Sweet Conciencia, a quiet little girl with her head down and with a side glance was placed with the poster-children for prophylactics, as one teacher put it. Conciencia was kept in this class since the first grade because despite all attempts, she wouldn’t learn English.

“What day of the week are we in?” Her head down.

“Is it raining outside or sunny?” Shrugged shoulders.

“Your name? Conciencia? What mother would name a child that?” The teacher muttered.

It wasn’t all failure or waste of time. By fifth grade Conciencia had learned how to stick her middle finger out, shout, and chase her classmates. Poor Mrs. Neally, the new teacher who came so prepared with her lesson plans and wide blue eyes, tried to teach them what verbs and nouns were. She was the only teacher who truly cared for them. The poor woman spent half of her lunch break crying in the ladies’ bathroom.

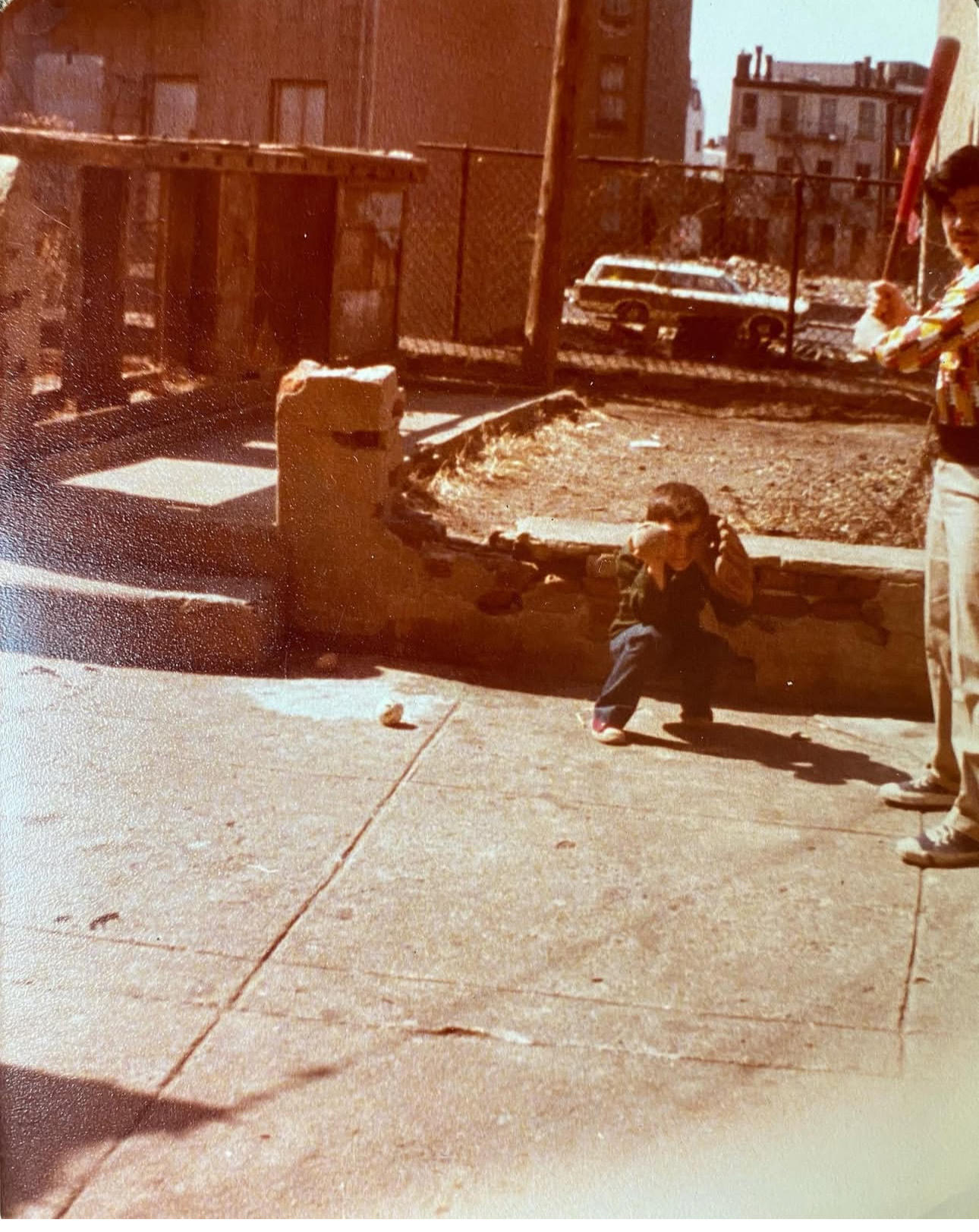

Conciencia learned to turn tables upside down, to hide in the wooden closet. She practiced robot dance moves. “Do the pump,” her classmates demanded, and she danced, her chest pounding to the beat of her friends’ fists against desks. Little by little, she learned to speak English and stand with her chest as high as her chin, “Yeah motherfucker,” she told Corey who towered over her, “you have a problem with me, yeah, well fix this problem! You black slave.” And everyone laughed, ha ha! And Corey would respond, “Yeah, spic, take a fucking bath and get some socks. It’s winter. And you blacker than me stupid.”

“Yeah,” Conciencia said, laughing so much she was barely understandable, “I saw a pig fucking your momma.”

“I saw your momma sucking a pig’s dick,” Corey answered back.

They went on and on. There was no fighting. They all stood together in this class. But God forbid someone from another class messed with them. That rarely happened. They had named their class, their crew—The Innocents, because as Corey said, “We are innocent until proven guilty.”

Sandra, who was two years younger than the rest of them, but taller than all of them, was either under her desk or standing on it.

Julio cried for a reason no one could understand. He would hide in the closet to cry and when he came out, he was angry, kicked chairs and fought anyone who would come near him. He sat in a corner of the room, and everyone knew to leave him alone until he was ready to join them.

Angel was put in special education classes because even at the age of eleven, he read as if he had rocks in his mouth, vowels trying to roll over the rocks and consonants drilling holes into them. His long hair covered his sad honey-colored eyes. Because of the way he whisked his hair away from his face, a few boys in the hallway whispered, “is he a faggot?”

There was Melinda who came to school with spray paints and tagged the tables whenever the teacher turned her back. Mrs. Neally would ignore the sound and smell of the spray and kept writing on the board. Nobody told on Melinda. In her long bathroom breaks, with Conciencia as guard, she painted a mural that included flowers, an ocean and the words ‘fuck you’ in turquoise.

Their classes were relegated to the third floor, the side of the building where the sun shone most. There were swinging doors separating them from the regular education classrooms. Regular Ed students looked through the small square windows on the metal doors to get a peek at students who were just hanging around or sitting on the hallway radiator. Sometimes the smell of cigarettes would sift through the doors. The best days were when they could get a look at a fight or a wooden desk being thrown against the wall.

4

The first time Juanito entered Conciencia’s classroom, they all looked at him as if he were the fish they were trying to bait. A new kid to taunt and beat to see how much heart he really had. He grew his dark hair into a short, tightly curled afro. On his chest gleamed a gold medallion with the island of Puerto Rico on it. When the teacher left the classroom to investigate the commotion in the hallway, Conciencia and Corey, leading the group, surrounded Juanito.

“Hey punk,” Corey said, “you speak English?”

Juanito reached into his right sock and with one quick movement, brandished a shiny blade. Corey looked at Conciencia.

Conciencia told Juanito, “Put that blade away before the teacher comes back in.”

After the three o’clock bell and they were outside, Conciencia told Juanito, “Join us. We’re The Innocents.”

Juanito had more muscles than anyone else. His chest could not help but stretch the buttonholes of his green shirt.

“Why are your eyelashes white?”

Conciencia didn’t answer him. Instead, she asked again, “Well, do you want to be part of us?”

“Who’s the leader?” he asked.

“I’m the leader. This is the last time I will ask.”

They shook on it. They walked home together and realized that they live on the same block.

“There are six rules to follow. You have to memorize them.”

1) No fighting between us.

2) If anyone messes with any of us, we’ll be there to defend our friend and be part of the retaliation, if necessary.

3) All members’ book bags and notebooks will have The Innocents graffitied on it by Melinda.

4) I am the head of the group. If you have problems with someone else in the group, tell me about it.

5) If any of us come to school hungry, then the ones who can will sneak in food for them. You can count on me for guava empanadas.

6) If anyone needs clothes, Sandra’s mom knows how to sew.

“Why are you in charge?” Juanito asked.

Conciencia replied, “Because I can read and write in English and because I can fight.”

5

There was no explanation given as to why the broken window in Conciencia’s class was never fixed or boarded up. The whole rectangular window including the wooden pane was missing. Kids sometimes threw books out there. Sometimes they spit just to watch their saliva go down four flights. Through the frame of the window they could see the block across the street: There were only three buildings there. Two of the buildings were abandoned. One of them looked like it had been sliced horizontally in half. You could only see the first floor and only one window on the second floor of a six-family home apartment building. Next to it was a building missing a roof. Sometimes teenagers playing hooky snuck inside them. The third one did have people living in there. One could tell because a Puerto Rican flag hung from the third-floor window. Surrounding the buildings there was gray rubble, junk yards and dust rising from the rubbish.

6

Conciencia became the best reader of the class. Maybe it was because she had finally found a stable foster home, and more than anything she wanted Doña Nina to be proud of her.

On a day that Conciencia was looking out the window the assistant principal, Mrs. Smith, asked her to follow her to her office.

Conciencia sat in the office and stared at a framed photo of Mrs. Smith’s family. Her children, three of them with blue eyes like their mom’s sitting around a huge Christmas tree, bigger than any that Conciencia had ever seen. Her husband smiled, pointing at the Rudolph nose on his sweater. Conciencia sat on a wooden chair that rocked every time she moved. Mrs. Smith sat behind her desk with papers organized and clean. An office with no window.

“I have good news for you,” Mrs. Smith said with a smile. “You scored on a ninth-grade reading level on your state tests.”

Conciencia, who wasn’t fond of showing emotion to adults, said nothing.

“First though, I have to ask this question. Did anyone help you with the exam?”

Conciencia was taken aback. There was a teacher there the whole time. The seats were spread out so no one would cheat. “No,” she finally answered.

“Ok then, we have decided that we will place you in Mr. Singer’s class, where you belong now.”

“You mean, you’re switching my class?”

“That class will be more appropriate for you. You’re going to love it there.”

Conciencia thought of throwing Mrs. Smith’s family picture against the wall but decided against it.

Mrs. Smith walked Conciencia back to her classroom and asked her to grab her things.

Everyone including Juanito and Corey asked, “What’s going on?”

“Come now, Conciencia,” Mrs. Smith insisted.

“I’m not leaving,” she said, drumming her fingers on her desk.

“My child, you don’t have a choice.”

Mrs. Smith used the phone inside a metal box against the wall to call security.

Mr. Banner, the 6’ 4” gym teacher that most students were afraid of arrived first. “All right, let’s go sweet tart,” he told Conciencia.

She didn’t respond.

“Do you need some help getting up?” he asked.

Conciencia turned her head and looked out the open window. Mr. Banner put a hand on her shoulder. “Get up on your own or I’ll carry you myself,” he shouted, “This is my lunch period.”

Mrs. Neally tried to intervene, “Maybe give her a day to think about it?”

“Take your hand off my shoulder,” Conciencia said through clenched teeth. She looked back at Juanito, who was rubbing his hands together as if he were trying to make fire.

“All right,” Mr. Banner said with a smile. “I guess you’ll have to be dessert.” He yanked Conciencia’s elbow and tried to lift her, but Conciencia had wrapped her legs around the legs of her desk. Her body, chair and desk fell to the floor, her head taking the brunt of the fall.

“Get your hands off her,” Juanito shouted.

The security guard arrived and held Conciencia’s arms, Mr. Banner held her legs.

Juanito asked Corey to repeat rule number two. “If anyone messes with any of us, we’ll be there to defend our friend and be part of the retaliation, if necessary.”

At this, Juanito, Corey, Julio, Sandra, Melinda and Jonathan got up. They grabbed their chairs and began to strike Mr. Banner. He was hit so hard that he dropped his hold of Conciencia. He dropped his hold of Conciencia. Corey took off his belt and struck the security guard in the face with the metal buckle. Mrs. Neally was in the hallway crying for help. The assistant principal was nowhere to be seen. The whole class, except for Angel, got up and pummeled the security guard and gym teacher.

In less than ten minutes, the police arrived and the whole class, even Angel, who had done nothing, were handcuffed, faces against the board, chalk dust painting their skins white.

7

Conciencia prepared the empanadas that Doña Nina taught her to make. She looked forward to surprising her and Doña Nina’s two friends as they returned from Sunday Mass. Conciencia had filled the empanadas with beef and potatoes and on a separate plate her favorite empanadas, the sweet guava and white cheese ones. She used a dish towel to wipe the sweat off her forehead. It was a 100-degree July day. The only thing to cool them off was a window fan that she turned off because it was making the paper napkins flutter across the counter. She focused on creating perfect ridges around the half-moon shape of the empanadas, so focused that she forgot about the oil bubbling in the pan. When she turned around a fire was blazing taller than she was. She knelt, picked up one of her chancletas and tried to put the fire out. Instead, the fire attacked her blouse. Her skin. She dropped to the floor unconscious. The fire spread to the walls.

Juanito was playing handball on the courts on Troutman Street when he saw the smoke rising.

“Conciencia’s house is on fire!” his friend Pito yelled.

Juanito ran fast toward it, his legs felt like rubber.

People covered their noses. “Where are the fire trucks? ¿Donde están los bomberos?” People cried.

Juanito tried to enter from the front wooden doors, lit like logs in a fire pit. Juanito took off to the apartment building to the left where the front doors were never locked and had a basement door that flung freely. He ran down the basement stairs, ran up the stairs that led to the yard, climbed over the yard fence to Conciencia’s yard, jumped on the window ledge and elbowed the window fan till it fell. He could see Conciencia on the kitchen floor. The fire had risen, but saints conspired in whispers and left the ground where Conciencia lay untouched.

He crawled on the ground, grabbed Conciencia by her arms and dragged her over the window ledge. He carried her body down the basement stairs and out of the building. Once outside he yelled, “Help, help, help me!”

There was smoke. Coughs. Men, children and women crying. Another building caught fire.

People sliced the air with their hands as if cutting cane, shouting, “Where the fuck are the fire trucks? ¿Dónde está la ambulancia?”

Juanito knelt over Conciencia’s body, “Wake up Conciencia. Wake up.”

The flesh of her chest was exposed like a pink carnation. There was a smell like burnt pork, burnt hair and another foul smell Juanito had never experienced before. One of the neighbors, Indio, got his car and helped Juanito carry Conciencia’s body into his car. “We’re taking her to the hospital ourselves,” Indio yelled.

Juanito sat in the backseat with Conciencia on his lap. “Wake up, Conciencia.” His chest heaved like a wrath filled wave. He checked her wrist for a pulse the way he had seen on TV. He was sure he could feel one. He held Conciencia gently in his arms. He bathed his head in the smoke rising from her body and chanted, “Let the smoke cleanse my mind. The most important thing right now is that Conciencia lives. If she lives, I will stop smoking, stop stealing, stop fighting, stop skipping school, dear God, dear Lord Jehovah or Jesus, God. Ven, ven, Papa Dios, aquí. Ven, Papa Dios. Curala, Señor, curala.” He sobbed in the mist of her body.

At the hospital, she was left on a stretcher in the hallway. Above her, a gap in the ceiling, powdered dust on her body. Cockroaches zig-zagged across the floor. When Juanito screamed at everyone in the emergency room, an attendant screamed back, “We are doing the best we can!”

If it hadn’t been for Juanito, Conciencia would’ve perished. The firemen had been busy putting out a fire in the neighboring community of Ridgewood, where historic brownstones stood and Puerto Ricans weren’t welcome. By the time the fire trucks finally made it to Bushwick, four buildings and the old lady on the third floor of Conciencia’s building, who never left her apartment, had been consumed by the fire.

Conciencia for the rest of her life did not grow breasts. Instead on her chest blossomed a black orchid, a shield that protected Conciencia’s heart from any further suffering.

* * *

Part II

1

“What do Puerto Ricans have to be proud of anyway?” Mr. Heitman asked our seventh-grade class. He was mad because he got caught in traffic yesterday because of the Puerto Rican Day Parade. “Name one thing, Conciencia,” he asked me. He then asked the same question to everyone else. My heart beat fast and my face got hot. None of us said anything even though almost all of us were Puerto Rican. We all got quiet. “That’s what I thought,” Mr. Heitman muttered. We were quiet for the rest of the day. We didn’t even play with each other during recess.

Mr. Heitman wrapped Sandra’s long ponytail around his big hands and pulled it real hard just ‘cause Sandra poked her head inside his classroom. With tears and snots, Sandra told her teacher, Mrs. Rubenstein, what Mr. Heitman did. Mrs. Rubenstein gave Sandra tissues and told her that maybe Mr. Heitman pulled her hair because her hair was so pretty.

Mr. Heitman turned the lights off and locked the door in the room me and Sandra were in. The Science teacher asked us to get folders from him. Since the room was in the basement with no lights, we couldn’t see anything. We asked him to turn the lights back on, but he didn’t. He didn’t say a word. We didn’t know where he was in the room. “Turn the light on,” Sandra said in her tough voice. I stood still. I didn’t know if he was coming to us. I thought I heard him tiptoe. I grabbed Sandra’s hand. Was he going to hit us? Was he going to touch us? Somebody said he got a student pregnant, but he was still in the school. “I’m not scared of you,” Sandra said.

I squeezed Sandra’s hand. I whispered in her ear, “if you keep talking, he’ll know where we are.” Since Sandra was bigger than me, she put herself in front of me to protect me. Mr. Heitman then turned the lights on and laughed. “Why were you so scared,” he laughed again. “What did you think I was going to do?”

2

Corey has an uncle who owns a pet shop named Malik’s Bushwick Pet Shop. It’s right underneath the J train on Broadway. Ever since the fire me and Mamá have been living on the second floor of the pet shop, which until then, Corey’s uncle, Mr. Malik, had been using as storage space. There’s a basement too, but no one is allowed there, except Corey’s uncle and his friends. Corey’s uncle has a lot of friends. They usually come in groups and they’re always calling each other brother and sister. They’re the ones who brought up a bed and other furniture for me and Mamá or Doña Nina as everyone else calls her. They wouldn’t take the money Mamá tried to give them for the furniture and help. “Ellos son gente buena,” Mamá told me. Even though they wouldn’t take Mamá’s money, they couldn’t say no to the tray of hot empanadas she made for them.

I love the pet shop. I go there to watch and play with the animals. The pet shop has frogs, bunnies, gerbils, a lot of fish, snakes, some baby cats and a lot of baby rats. Mr. Malik forgot to take a female out of the cage and now they are multiplying. Most of the time, Corey’s uncle is reading The Amsterdam News newspaper or listening to the radio. He made Corey and me go quiet, “Shhh,” he said, “Malcolm X is talking.” Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet? Who taught you to hate your nose? That made me think of Mr. Heitman. I heard him say to Mr. Simon that he would give me a five out of ten. He would’ve given me an eight, he said, if it wasn’t for that big nose. It’s bigger than her face, they laughed. They didn’t know I was listening. Mr. Simon rated Sonia a ten because of her green eyes. They said I had a nice body, but that nose. I think Mr. Heitman wants me to hate my nose.

Corey’s uncle is always asking me and Corey what we learned in school, especially history. Corey and I are in different classes, but we have the same teacher. Mr. D sits behind his desk reading the New York Post or Daily News. We tell Corey’s uncle we are learning about the Civil War and how Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves.

Corey’s uncle’s face grew angry. “He didn’t free us,” he told us, “We freed ourselves. They just don’t want you to know how powerful you are.” I also told him that Mr. Heitman said that Puerto Ricans have nothing to be proud of and said I had a big nose. Corey’s uncle’s eyes bulged and he slammed his right fist into his left hand. “You’re beautiful Conciencia,” he said, shaking my shoulders with so much force that I felt like he was waking me up from a bad dream.

Mr. Malik has a Puerto Rican girlfriend, Diosa. She wears wide bell bottoms, short blouses and has a short afro. She is a poet. She likes me. I can tell because she reads me some of her poems. A lot of them are about Puerto Rico, fighting for justice and some are in Spanish. “You don’t have to use periods or capital letters?” I ask her. “No,” she tells me, “In poetry you don’t have to do anything you don’t want to.” Next time she sees me, she says, she will bring me a journal and pen so that I can be a poet too.

I think Mr. Malik may have told Diosa what Mr. Heitman said about my nose because she sketched me and wrote the word beautiful around my nose. She also talked to me about community and how Puerto Ricans and Blacks are a community. How we look out for each other, how friends and family are community. That made me feel real good to know that I was part of a group that was about love.

3

When I was in eighth grade my classroom teacher told me that my grades were the highest in the school and that I was going to be the valedictorian. I had never heard that word before. I was sent to the head of the English department, to Mrs. Fitzgerald to help me with my speech. My teacher said, “Write something first, a draft, something that will inspire your classmates and then Mrs. Fitzgerald will help you polish it.”

This is the draft I read to Mrs. Fitzgerald:

My message to you is that community is important. You need to find people and friends that care about you and love you. Like my mom, Dona Niña. She took me in when I didn’t have a home and because of her I am standing here today. I got good grades because I wanted to make her proud of me. She taught me, “Dime con quién andas y te diré quién eres.” Tell me who you walk with and I will tell you who you are. That’s true. I walk with Corey, Juanito, Sandra, because they have my back. I am part of my community. So my message is for you to find a community, people and friends that will make you feel loved.

When I showed Mrs. Fitzgerald my speech, she shook her head and said, “No, this is not a valedictorian speech. And you can’t write it in Spanish. No one is going to understand you.”

I grabbed my speech, in case she had planned to tear it up. “I had a feeling,” Mrs. Fitzgerald said, “that this would be hard for you so I’m helping you with this. Here read this aloud. I wrote it for you. I’m still trying to think of a quote to start you off. Quotes are good ways to start a speech.”

I took what she had written in fancy script and read aloud, “As we climb the ladder of success and wake to a new dawn…”

She stopped me before I could read further. “The word ‘the’ does not start with the letter d, it’s not ‘duh’ say ‘the’ again.” I said ‘the’ again, but she shook her head then buried her head in her hands. She looked up, “Look at my mouth,” she said, “look at where I place my tongue. My tongue does not hit the back of my two front teeth. The tongue is underneath the teeth.” Her tongue brushed the bottom of her two straight front teeth from side to side. “Next,” she said, “let there be a little space between the teeth and tongue, and you let a little bit of air slip out between the teeth and tongue. Like this.” A little of her spit landed on my cheek. “Look at my tongue,” she said again. Her tongue was flappy, and I couldn’t help but think of the dogs that were set loose on the children of Alabama when they protested segregation. Corey’s uncle showed us a 1963 newspaper clipping of that day, of white policemen siccing German Shepherds and water hoses on black children like me, my age, eleven, twelve, thirteen, fourteen. Mrs. Fitzgerald’s tongue was like a whip in the flesh. I wonder who would win a fight between a dog and me. If water hoses were attacking me too I would die, but maybe if I had a knife or scissors, I could cut the tongue out of those dogs. I might win.

4

On graduation day, I wore a beautiful white dress that Mamá made for me. Many people went to Mamá for special occasion dresses. They would come with magazine clippings of fancy dresses that cost over a hundred dollars and Mamá would make it for a lot less. Mamá also made me two thick braids with red ribbons intertwined in them. She chose the colors. She told me that she wanted me dressed in Santa Barbara colors. I looked in the mirror and imagined having a sword like Santa Barbara. I wasn’t sure if on a day like today, I would need to raise the sword in war or dig it in the ground for peace. The white of my dress, peace, the red in my hair, fire.

Once we got to the school, I had to be patient because a lot of grown-ups talked. When Mamá wanted me to translate something, I did, but it was all boring.

My hands were a little sweaty from holding the index cards with the speech Mrs. Fitzgerald wrote for me. The quote she chose for me to start my speech, Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country, by John F. Kennedy.

When I made it to the podium, I turned the index cards to their backsides where I had written my own speech with my own handwriting. I knew it was good because Mr. Malik and Diosa told me it was perfect and to not change a thing. “You’re a poet,” Diosa said to me.

5

My Valedictorian Speech:

Dime con quién andas y te diré quién eres dice Mamá

tell me who you walk with and i will tell you who you are

i walk with Mamá because she loves me and kept me

i walk with the The Innocents because they have my back

i walk with Juanito because he saved my life

i walk with Corey and his uncle because they gave us a home after the fire left us on the streets

now i will tell you who NOT to walk with

Malcolm X says who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet?

who taught you to hate your nose?

maybe someone has told you that you do not know how to think

that you that you do not know how to write a speech

or insult Puerto Ricans because of the way we speak

maybe they stick their tongues out until you feel saliva sting your cheeks

maybe a teacher has told you that Puerto Ricans have nothing to be proud of

or that abraham lincoln freed the slaves

he did not

we freed ourselves

maybe they’ll turn water hoses on you or even sic german shepherds on you

tell me who has made you weak or scared

was it mr. heitman? mrs. fitzgerald?

what about our classmate who is pregnant and was not allowed to be here today?

she has told us that mr. heitman got her pregnant and yet nobody believes her

i believe her

why isn’t anyone asking us

what we think?

what we’ve seen?

what we’ve felt?

as valedictorian i demand an investigation into mr. heitman

we demand that no teacher put their hands on us again

we demand African history classes

we demand that you not humiliate our parents

The Innocents have written a petition with our demands and now we will see who you walk with

i walk with gente buena, good people

Malcolm X says

we love everybody who loves us,

but we don’t love anybody

who doesn’t love us

The End

6

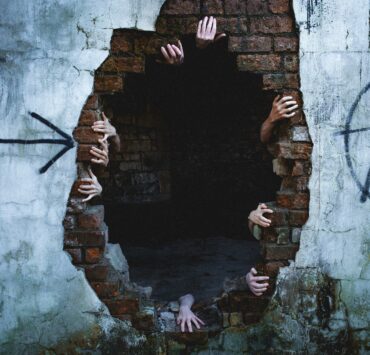

We hear it first as a big gasp of air, then a deep moan, then a high screech voice, then we hear him knocking things down. Somebody help he screams. Mr. Malik has helped us lock Mr. Heitman in the school basement room. We see the little rat feet trying to get out from under the door. But the rats can’t get out so they scurry back inside the room, where Mr. Heitman is now crying. Rats are not violent by nature, but because Mr. Heitman started throwing boxes at them, their survival instincts kicked in and they climbed his legs, past his private parts to his stomach, to his mouth, where he had been eating peanut butter and they took little bites of his lips and tongue. They drank the salt of his tears, they took many, many bites from the tip of his big nose so when Mr. Heitman was discovered in this room two days later, he had a missing nose tip. The tip of his nose is pink now and now we know who Mr. Heitman walks with. He walks with the rats.

* * *

Image by the author

Alba Delia Hernández is an award winning writer, inspired by Puerto Rico, growing up in Bushwick, and salsa, who dances in the hybrid forms of fiction, playwriting and poetry. She was a featured reader for The Bushwick Starr’s 2023 Reading Series and was awarded the winner of the 2022 One Festival for her one woman show, Juana Peña Revisited. She is a recipient of the Creatives Rebuild New York (CRNY) Award, the Bronx Council on the Arts First Chapter Award and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Columbia University. Her writing was highly commended in A Gathering of the Tribes Magazine, El Proyecto de La Literatura Puertorriqueña through the University of Houston’s USLDH and the Mellon Foundation, and other publications. She has performed at El Museo del Barrio, The Whitney Museum, Nuyorican Poets Café, La Respuesta in Puerto Rico and other venues. She’s a passionate yoga teacher, salsa dancer, and videographer who recites speeches by Puerto Rican revolutionaries or moves to songs of resistance.