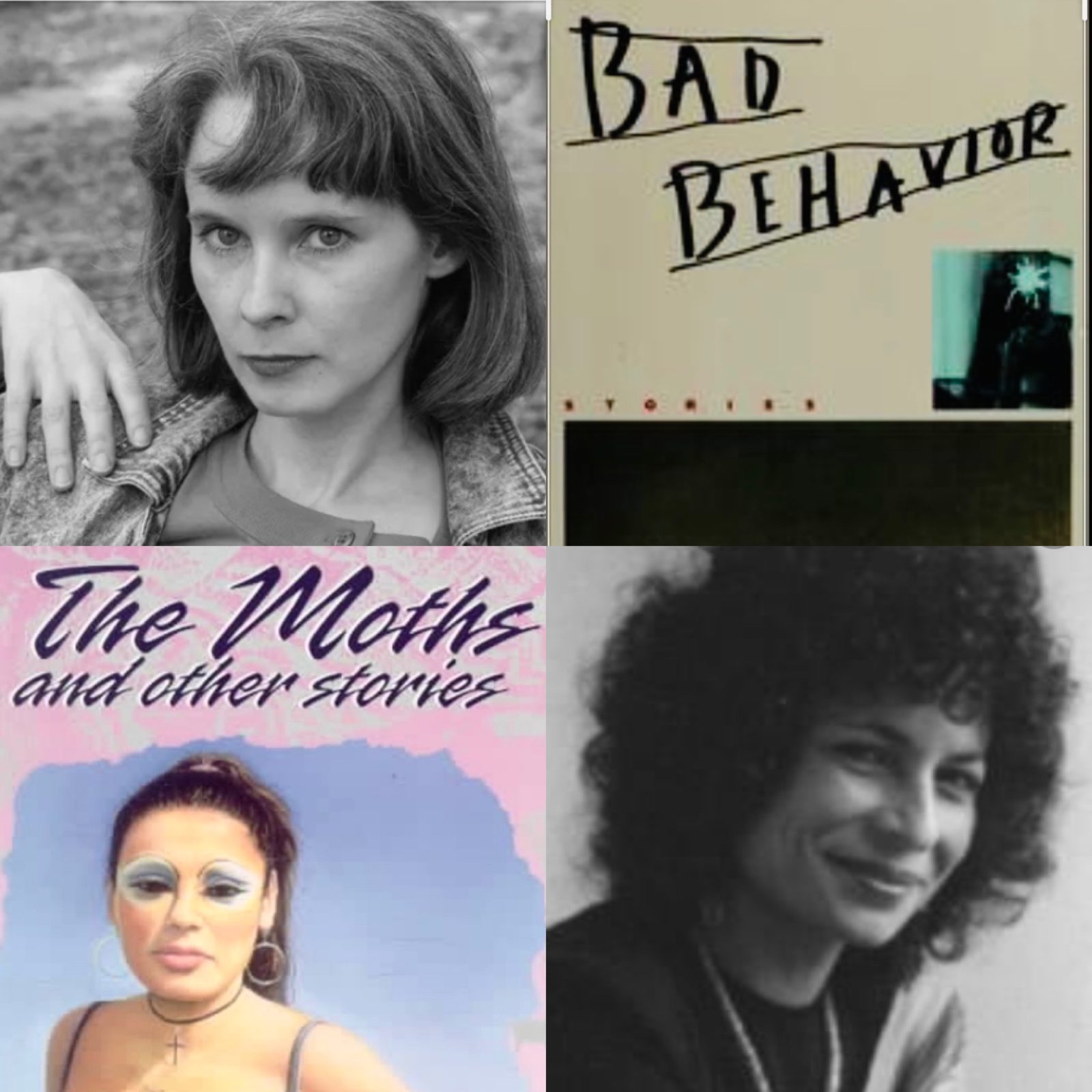

On November 11th 2016 Mary Gaitskill and Helena Viramontes shared a stage for the first time in their literary careers. Both were born the year of the horse in 1954 and had their first short story collections published in the 80’s: Viramontes’ The Moth And Other Stories in 1985 and Gaitskill’s, Bad Behavior in 1988. Both writers have been critically celebrated for depicting strong female characters in a straightforward and unclipped way around “taboo” subjects. The conversation was a part of the Aster(ix) reading series at Alphabet City @ City of Asylum located in Pittsburgh. That evening, was also Election Day and welcomed the distraction of listening to Gaitskill read an excerpt from her new novel, The Mare and Viramontes read from her forthcoming novel, Cemetery Boys. After, we had a riveting conversation about the challenges women writers face.

Angie Cruz: You worked with the author of Corregidora, Gayle Jones back when you were still a student and I’m wondering what was that experience like for you?

Mary Gaitskill: When I met Gayle Jones—this was before writing programs—there were no writers who taught at the University of Michigan, and so I was very eager to meet this person and she was so unlike the other professors. She didn’t speak any kind of academic language, she didn’t speak at all unless she really had something to say. She was very quiet and when she looked up at you and met your eyes, you felt she was really contacting you. She didn’t really know how to teach creative writing classes, it turned out—she’d never been in one—so she didn’t say very much and by today’s standards it wouldn’t probably be a good class. Except that when she did talk it really meant something and it wasn’t just any kind of received wisdom. I remember when I would meet with her in her office, the first time she said to me, I think you’re a real writer, it really meant something. She was just not like the other people at the academy at all. And I’d mentioned her once to an English professor, and I said she liked my writing, and she almost rolled her eyes and said, well she’s had one book out. And that made me realize even more so that she was very alone in that environment.

Helena Maria Viramontes: What year was it?

MG: That was a long time ago. That was like ‘79 I think. Maybe even ‘78.

HMV: At that time there were only a handful of MFA programs. I was one of the first Chicanas to be accepted into the MFA program at UC Irvine, and this was in ‘79. And they didn’t know what to do with my work. Most of the collection, The Moth and other stories, was written there, and I remember my advisor coming up to me and saying, You know what Helena? The trouble with your work is that you’re writing about Chicanos. You should be writing about people. So I started to think, this whole idea of universality, what the hell is that? Who defines what universal is? And so I tried to think about why he told me this. This was one reason I left the program and didn’t go back until Thomas Keneally took it over. I never forgot about that. It was just like that professor who said to Mary, oh but she only wrote one book, you know? These are things that stay with you.

You just have to remember that for a long time there weren’t any MFA writing programs. Back in ‘79 there was maybe about thirty. Now there’s over three hundred, three hundred and fifty with low-residencies and PhD’s. Before that we learned just by creating. I don’t know what your experience was, Mary, but we were creating our own communities. We just met with each other once a week, at the Latino Writer’s Association, we published our own work because nobody published us. Nobody would even look at our work. So we said to hell with that, we’ll make our own magazine. And we did. And now it’s archival. Archived in number of libraries.

AC: A number of years ago I met Sandra Cisneros in Texas and she insisted that I pursue a friendship with you Helena. She said something like, you’re gonna love her because she’s an activist and a writer like you. That we were kindred spirits. But she also said but you’ll have to persist because even when she was invited to be in the Sundance Institute to work with Gabríel Garcia Márquez, she didn’t say yes right away!

HMV: No I didn’t.

AC: So did you eventually go work with Gabríel Garcia Márquez.

HMV: Yeah. Yeah. That was an amazing experience but I have to tell you I declined when they first asked me, and part of the reason was because of the language. I grew up being punished for speaking Spanish. And so as a result we didn’t speak Spanish, although at home my parents both spoke Spanish to us, so I come from a whole generation of people who can understand Spanish but don’t speak it. So that’s the way I explained it. I said, I can’t because Gabo wanted us all to do presentations in Spanish. They came back and Gabo said, I understand English, I won’t speak it, but I understand it. So you can do your presentation in English.

And then I said no a second time. I said, well I have my kids! And he said bring ‘em! So that’s when I told my husband, Eloy, you know what I think this is, a sign. I need to go. But it was an incredible experience to be there ten days with him, and for three or four hours a day. Basically, he was a masterful storyteller. Although, every day was very quiet because he was of course a great friend at that time to Castro, and people thought that his life was fragile. There was some kind of danger. And so this kept us all very quiet when he came here to do Sundance.

AC: And you Mary, throughout your career you have written and referred to Nabokov quite a bit. So you love Nabokov?

MG: I do.

AC: In one interview you said, “sometimes I write from the point of view of characters whom I would dislike as people.” I’m wondering what are some characters you’ve started writing that you disliked? In particular in The Mare being that The Mare is a novel I know well, because I was given the opportunity to read it while you were revising it,

MG: I’m not sure there’s anybody I dislike in The Mare. There’s one character—well actually there are a couple characters. But there’s more characters in my short stories. What’s interesting about it is, if I put myself in their bodies as I move through the world, I can see through their point of view and it’s just a lot more interesting than if I put myself in the point of view of characters I only like. It’s like all the weight is on one end, and it’s kind of all tipped over. Have you ever been in a situation where you meet somebody, and everything you heard about them leads you to believe you wouldn’t like them? They’ve done really bad things, even. But when you meet them, being in their physical presence, and looking at them and hearing their voice, you can’t help but like them. It’s a very strange thing when that happens. And it’s got nothing to do with morality, it’s somehow connecting with them and understanding that in some place inside them, whatever they’re doing, makes sense at the time.

Velvet’s mother is not a character that I would approve of in life. She really treats her child badly by my standards. But if I think about meeting her, and looking at her, and being with her as she moves through the world, it gets into a place that’s not even about liking her or not liking her. She has certain choices to make and certain places to move and I understand why she might move in this direction that I wouldn’t approve of. That’s a very abstract answer. But I just think it’s much more interesting to me to be in the point of view of a character I wouldn’t necessarily sympathize with. It makes me look at the world differently.

Audience member: Hi this is for Helena, but I think Mary might have something to say about this as well. I was thinking about your reading, about how you kind of zoom out and we get a sense of all of America and the world maybe in some bits. And then we zoom back in to what’s happening with people and the way that geography kind of works metaphorically, right? Mary, your reading was much more about the sale and moving into the memory, and back and forth. I’m just thinking about how cosmic and more intimate scales of things can play into one another, and how you think about space as you’re writing.?

HMV: Yeah.I don’t know why I do these things because I have about three-hundred and sixty pages of this novel and it’s not nearly finished. I’ve put myself in a situation where if I’m writing about this particular time, then the story doesn’t just belong to this Mexican family. That it belongs to the Punjabi community that was in southern California. It belongs to the Chinese who put the railroads in. It belongs to the Japanese because World War II very much affected them with internment camps. And Los Angeles, which had incredible intersections of these communities. Mary talks about embodying, and I think that’s the only way to do a character and that’s why it’s so petrifying. I try to embody. I just finished a section on a Filipino man who comes in 1914 to California, works in the fields, reads about the canneries. There was this group of Filipino men that went all the way up to Alaska to work in the canneries. And I just think, such an important thing because of the sacrifices they made to never go home, losing their families completely. It’s something that I have to write about. I try to embody this. I try to embody the Punjabis, the Sikhs, just reading the Sikh bible, just looking at that in ways and try to not emulate—but to be. And it’s hard, it’s hard! But if I’m going to do it I have to do it right, because to exclude is what has been done to me. To my people, to my history. So I cannot not include them as well. There lies the challenge. Where you have big sweeps, but of course—I always tell my students big ideas, but it’s the small problems that count. But it’s hard.

MG: I guess my answer to that would be similar. What’s most touching to me is a small person, like a 13 year-old girl, who doesn’t know a lot of historical information but is nonetheless feeling it, as if she’s meeting it with her body. And we all are. Some of us are more aware of it than others, some of us feel it, are more on the receiving end of it than others, getting more of the bad end of it than others. But the most touching thing to me is this small person up against big social forces that she maybe isn’t ready to understand with her head but she knows very much in an intuitive way because she can feel them.

HMV: That’s a good answer. When you think about the colonized body, you know “the body”, and all of a sudden you have these forces that don’t know the history. You know, the feelings of self-hatred, the feeling of things being unfair, that’s all about the colonized body. It’s just like that. Fantastic.

Audience member: I’m from Nigeria, I’m a writer too. I come from a community where women judge. One of the questions I always get is, you write a story about a woman having an affair? The response is always to be judgy, and the query contains religious and cultural expectation from the community that women must respect, they should not cross certain lines. They query if this is your life story, are you writing about yourself? And all these negative responses, even before they begin to criticize the system. So when Angie was introducing you she said that most of your earlier works were along those lines, exploring taboos. So I want to ask, did you face such criticism?

HMV: I’m a child of the Sixties and Seventies, and so the Civil Rights movement was going on, the Women’s Movement was going on, the Chicano Movement was going on. Within the Chicano Movement, there was always this division between Chicanas and Chicanos. The male leaders would say, you cannot talk about women’s issues because they are dividing us. As if women’s issues were not part of any political movement. And so we just began responding in that way. There’s been sacrifices that we’ve had to suffer because of that. But if we don’t speak up who will? I mean if we don’t say, what about the children, as Mary was saying, these young girls, what will they learn? How will they learn? If we don’t speak up and say something.

So when Edna O’Brien was first writing about lust and love and Ireland, they would throw rocks at her house, you know? And now she’s been listed for the Nobel Prize. We cannot afford to be silent. We just cannot afford it. And so we’re just gonna have to get those role models like Toni Morrison, people like Gayl Jones, people like Mary, for example, who writes about these really interesting, complex relationships. For me, all I want is to go to my little room and to write, you know? But I can’t do that at times, because other people are suffering. I have to come out and I have to speak out. Silence is your worst enemy. I worked with a writer from the City of Asylum in Ithaca who was from Zimbabwe. NoViolet Bulawayo was my former student. And we really worked together because Zimbabwe was falling apart and I was so worried about her. I was so worried because she couldn’t go home. And there she was, a student. The privilege that she felt for being in the United States to write about it, that’s the power that you have. The words. Write it. And then make it an American book too. And then she was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Fantastic novel.

MG: I wasn’t sure I heard you right. Were you asking if Helena or I experienced any intense, negative criticism for writing about women having affairs? Yeah, definitely. What’s incredible to me is that on the one hand, everything is so open and we can talk even about changing genders, and there’s a place in America where you can talk about almost anything, but still in the mass culture there’s an extraordinary lack of acceptance and hatred and fear of women’s sexuality. It’s incredible. Even in the most florid situation, where you can go online and see porn, the Kardashians are talking about their asses and showing their bodies constantly, still these really fundamental fears and prejudices exist. One male critic said reading me was like “getting fucked up the ass with a dildo”. I mean, what? What? I’m sorry to be vulgar. But in a way it’s a huge compliment. I’ve never read anything in my life that gave me that kind of sensation before! I really wondered what he’s thinking. I don’t think I’m talking about anything that horrible. But it still really upsets people if you talk about women having sexual experiences or having certain sexual feelings. And it’s weird. I don’t know what’s happening in your country, but I don’t think what’s happening in this place is that much different. So there is negativity, but I agree with what she said. You still have to do what you can do as long as you can legally, which I hope it continues to be, in this country after the election.

Audience member 4: To follow up on the conversation of the last two questions. There seems to be a sort of dichotomy that that you both are writing and experiencing which is, though the writing itself is intimate, there is a sense of displacement that your characters sense and feel. And at the same time, you as writers have also been displaced as you both attested to in many ways. So I’m wondering, when you’re writing your stories, is that something you keep in mind? I’m wondering if when you are writing the stories, are you trying to correct the displacement? By making it that intimate.

MG: Maybe. I don’t know. I don’t think about it that way. I don’t think that writers usually have that kind of idea when they’re actually writing but I think that it’s possible that I’m trying to get some kind of understanding for people who feel, for any number of reasons, displaced or alone.

AM 4: For me there’s always this juggle, not juggle but bouncing back and forth between intimacy and displacement. And so for me as a reader to read that in a story, it is for me trying to understand how to correct that. Do you think your stories function in that way?

MG: I hope so.

HMV: Yeah I hope so too. I wouldn’t write what I’m writing if I didn’t have some kind of political understanding. Writing about my uncle in The Philippines, I couldn’t not write about the Filipinos in California who were part of the United Farm Workers, who were given a very small visible historical footnote. Part of this has to do with my political understanding and my understanding as a brown woman, as a brown body. So for that, I make certain decisions. But after that, it’s just the fiction that grows from it.

AG: Maybe one last question?

Audience Member 5: Both of you kind of mentioned bad advice that you got as writers. And I’m wondering, Helena you mentioned universality and this critique from a professor that you weren’t writing about people, and I’m wondering, was there a voice in your head that said, oh maybe this person’s right? Or did you reject it immediately and if so, how did you get to that?

HMV: I just thought about it. I thought, well that’s why I’m in a friggin’ program: to write better. But he was not criticizing my craft, my syntax, my narrative structure, my use of flashback. He was talking about the people. And those people were my family. I was writing about my mother, my father, my sisters. I grew up with six sisters. So my work is very female-based. So I knew right away this guy was bad news. I’ve been dealing with that comment for thirty years. I’ve written about three or four essays, trying to understand. That’s why I’ve gotten to the point of universality. Like what the hell is that? What the hell is that thing? But no it never stopped me. I left the program but it never stopped me from writing. And I just kept writing and in 1985 I published a collection The Moths. And many of those stories were there. And by 1989 I was in the Norton Anthology of American Literature. So when I returned back in ‘92 with Thomas Keneally I asked him, can I come back and finish my MFA? He said yes, so I came back and I finished it and I finally got my MFA. But no, I knew immediately this person did not understand and did not understand me.

MG: I actually haven’t gotten very much bad advice because I haven’t gotten much advice at all. The class with Gayl Jones was one of the only real writing classes that I took. I did have another class with an English professor but I don’t really remember it. So I didn’t get a whole lot of advice period. Sometimes my friends would read my work—I didn’t know very many writers either and didn’t have a group of writers. I was very much a loner. But my friends would read my writing and say, this is depressing. Or, why are these women so vulnerable? It makes me uncomfortable. I don’t like it. But I just didn’t pay that much attention. It was unpleasant though, I didn’t like hearing that, but I couldn’t help but write what I wrote.

Helena María Viramontes is the author of Their Dogs Came with Them, a novel, and two previous works of fiction, The Moths and Other Stories and Under the Feet of Jesus, a novel. Named a Ford Fellow in Literature for 2007 by United States Artists, she has also received the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature, a Sundance Institute Fellowship, an NEA Fellowship and a Spirit Award from the California Latino Legislative Caucus. Viramontes is Professor of Creative Writing in the Department of English at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, where she is at work on a new novel.

Mary Gaitskill is the author of the novels “Two Girls, Fat and Thin,” “Veronica” and “The Mare.” She has also written three story collections which are “Bad Behavior,” “Because They Wanted To,” and “Don’t Cry.” Her stories and essays have appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, Granta, Best American Short Stories and The O. Henry Prize Stories. She has taught writing and literature on the graduate and undergraduate level since 1993; She was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2004 and a Cullman Fellowship in 2010.

Angie Cruz's novel, DOMINICANA is the inaugural bookpick for GMA book club, and the Wordup Uptown Reads selection for 2019. It was also longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie award in excellence in fiction for 2019. It was named most anticipated/ best book in 2019 by Time, Newsweek, People, Oprah Magazine, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Esquire. Cruz is the author of two other novels, Soledad and Let It Rain Coffee. She's the founder and Editor-in-chief of the award winning literary journal, Aster(ix)and an Associate professor at University of Pittsburgh where she teaches in the MFA program. She splits her time between Pittsburgh, New York, and Turin.