Chloë Bass’s Wayfinding is comprised of twenty-four site-specific sculptures at St. Nicholas Park, across from the Studio Museum in Harlem. Through this, her first institutional solo exhibition, she invites the audience for collaboration by posing three central questions: How much of care is patience? How much of life is coping? How much of love is attention?

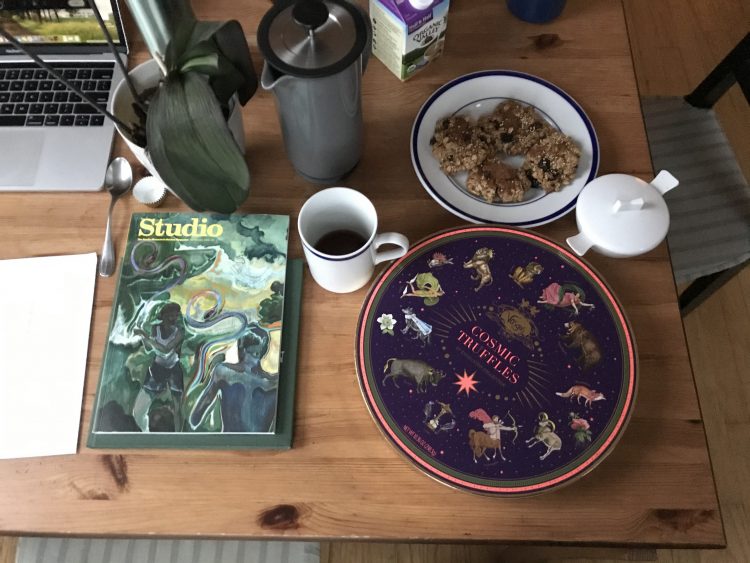

In search of answers, I visited Bass at her apartment in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, a neighborhood she’s called home for the last nine years. Her work, which examines what it means to be together at various scales of intimacy, is conceptualized and birthed here alongside the cadence of her every day. Over a long coffee with chocolate truffles and visits from her cat Tommy, we spoke about how language shapes our experience of intimacy, ways the art of translation threads into her practice, the complexities of public art/space, and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Helen Hwayeon Kim: Mmm, this cosmic truffle is delicious.

Chloë Bass: Wait, there is an accompanying text with it, don’t finish your chocolate. Let’s start with a reading.

HHK: Okay, ready.

CB: “To begin, breathe. Close your eyes. Take three deep Ujjayi breaths.” So this is like Chocolate yoga.

“Listen to the space between thought and prepare your palate to experience chocolate. See. Describe what you see. What is the shape, color, sheen, and texture? Touch. Run your finger against the chocolate, noticing its texture and releasing the aromatics. Smell. Bring the chocolate close to your nose. Close your eyes, cup your hand around the chocolate, and inhale deeply. Taste, enjoy your chocolate in two ways. Two bites for your chocolates,” which is a bit ridiculous since some of them are the size of a cupcake. Anyways—two bites.

“In the first bite, you are just getting to know the truffle. In the second, you delve deeper, searching up the aromas and nuances. As the tasting experience unfolds, place your intention on the chocolate, as it enters your body the chocolate carries your intention to your body on a cellular level. The finish. Breathe into your mouth and taste the lingering finish. You will be the judge.”

Things like this, I find compelling as existing pieces of text. It’s so silly, if I take out the word “chocolate,” and every time there’s the word “chocolate,” I replace it with a word like, “your neighbors”: a guided tasting of your cosmic…neighbors! Then, you are listening to the space between your thoughts and preparing your palate to experience your… neighbors. Cup your hand around your neighbors. Enjoy your neighbors in two bites!

HHK: Oh, yes, this can definitely be an art project or performance.

CB: But this comes from a fancy chocolate company that also knows where the money is, and the money is obviously in astrology.

HHK: Right, as someone who’s followed astrology for over a decade, it’s bizarre to me how mainstream it’s gotten.

CB: Yeah, what do you make of this? Because I have not followed astrology my whole life, and it snuck up on me as something that it is my responsibility to know as a creative person in the year 2019. You just have to know.

HHK: Honestly, I think it has to do with ways traditional categories that used to guide us have crumbled or failed. Categories like gender, religion, race, or nationality don’t elucidate anything about a person, and they obviously never should. Personally, I find it a fun and helpful framework for understanding myself. And I like that it’s rigorous but also operating on a magical terrain. That it is not of this world. It makes it lovely.

CB: Yes, I agree. We need different ways of looking at ourselves. Human beings are naturally inclined to classify ourselves in one way or another. I don’t know if saying I am born on the day of the Leo/Virgo cusp is more or less relevant than I am Black and Jewish, but the world has made it more relevant for me to be Black and Jewish. That is as arbitrary as anything else.

HHK: Do you feel there is a heightened sense of political or identity-driven dimensions expected from your art given our political climate?

CB: No, I don’t. I love that I am privileged enough that I can say that is not a requirement for me. I feel enough seen in the world. I can let people be different from me and have that be equally inspirational.

HHK: Let’s start with how Wayfinding came to life. How did the project come about? Did you know the project was going to be installed in Harlem, at St. Nicholas Park when you conceptualized it? Or did the concept arrive before the site and the institution?

CB: Here’s how it happened. Legacy Russell, who curated this show, started her position at Studio Museum in Harlem around September of 2018. She reached out to me when she started her job, inviting me to submit a proposal to do a public art project with the museum. I didn’t understand at the time, I thought I was in competition with other people, but she meant, “Tell me an idea that you want to do, and we’ll make it happen.”

HHK: It was a solicitation from the museum. So you got to be extra ambitious?

CB: Yes. If I had known initially how certain it was, I would have probably choked. I’m glad that I didn’t know. She and I went out for drinks, and she just told me to “think big.” I submitted a proposal for a project that became Wayfinding. We took the better part of January to June, really figuring out how that execution would work. And then, it was designed and built over the course of the Summer and installed in September 2019.

HHK: From your initial proposal to what we see at the park, do you feel it’s pretty close to what you intended?

CB: Yes, it’s pretty close. Because I don’t come from the “monumental art” background, I always think, “How do I highlight the things that are already here?” In public space, in particular, I think this idea works well. So I wanted it to be various scales of public signage. Then there has been an ambivalent relationship that I have with language in my work. Obviously, I am a highly verbal person, and I maybe have more training as a writer than as an artist. But also, I’ve been a little worried about how text-heavy my work is.

A friend of mine who I really respect and have worked with said to me, “You should do a project that doesn’t have any text at all.” I was like, that’s a good idea, but then I felt like it was a bad idea. I went back and forth, and I still don’t know! I don’t trust myself to be able to do that yet. I feel like people don’t know how the project will work unless I put the words in, but maybe I am wrong. That said, working within the idea of a monumental public text, it just has a different impact. And I don’t know how I would have gotten away from it this project.

HHK: How did the specificity of Harlem, and the fact it’s going to be installed in a public park, shape this work?

CB: Harlem is a neighborhood that’s not my neighborhood, and the work is for a community that’s not my community, although it’s a community that I feel connected to because it’s close to where I grew up. There are things that I know about Harlem, and there are tons that I don’t know about Harlem, and I didn’t want to presume that I could embed myself realistically in order to make this work happen. So when I gave myself permission to not pretend that I could do that, it became a much more open-ended thing in terms of how people might feel or respond. Because I made this, in some sense, for you [residents of Harlem], but also I have the only loosest understanding of who you are. So I wanted the workto be very present and visible, but I also wanted it to be kind of lightweight—not conceptually lightweight—but physically not feel too imposing while being large.

HHK: I think I know what you are getting at, the types of public art that demand or rob your attention. It’s screaming to be seen. In contrast, Wayfinding felt very welcoming.

CB: There are so many examples of public sculptures that totally change a place, and I didn’t want it to do that. Somebody said the nicest thing to me at the opening, one of my colleagues from school actually. He is very thoughtful but not the most friendly guy, but he came over after the opening and said: “I just want to say one thing. Really, these works feel like they’ve always been here. “And I felt, wow. That’s the nicest you could possibly say because that’s kind of what I am after. As opposed to a tremendous shift in the landscape of something that’s new, it’s almost like a revealing of what has always been there. Or questions or phrases that have always existed for us or that draw from something that feels familiar, even if you haven’t expressed it that way.

Also, the way the work is right now is not finished. I had a meeting with the museum yesterday to plan the next phase of what the work is.

HHK: Oh okay, I was actually going to ask about that!

CB: It’s not finished. The physical parts are finished, but it’s actually a site for a play, and I will be writing and performing in the play late spring or early summer.

HHK: Amazing. I know you’ve recently concluded the second project in your study on scales of intimacy with The Book of Everyday Instruction, which focused on one-on-one relationships. Where would you situate Wayfinding in the scale?

CB: Wayfinding is part of the larger project, Obligations To Others Holds Me In My Place,which I began about a year ago. It is the project about intimacy at the scale of immediate families, and technically it focuses on mixed-raced American families, although I think that it has implications beyond that. The way I work is, I do these multi-year, multi-part, multi-form projects that are all under a similar scale of intimacy, and similar kinds of guiding questions. How Wayfinding will fit in will not be clear until I finish. I am also making a film under this larger project.

That’s another thing that I think people find maybe unpredictable about me, they know that I am doing these large… I am no longer calling this “research-based work” because I am not a research-based artist anymore, I am an arts-based researcher.

HHK: So you are sticking with this one?

CB: I am sticking with it! I don’t research art, that would be terrible. I use art to research life. You know, my artist statement says I am a multi-form conceptual artist—those are words that don’t mean anything, but I sort of needed words that don’t mean anything to illuminate the fact that I am mostly thinking, and I don’t know what the outcome is going to be formally. But I am using life as the material for what I make.

HHK: How is Wayfinding weaved into the study on intimacy at the scale of immediate families?

CB: All of those questions, particularly the central ones that are on the billboards—How much of love is attention? How much of life is coping? How much of care is patience?—are actually based on how difficult or fraught it can be to be intimate with your family. Sometimes even with your own partner, right? It’s the most intimate relationship, but then sometimes you feel distanced and there are things you can’t ask and say, or there are ways in which you are not seen or not known, and I find that really interesting.

I think it also happens so much between parents and children. Of course, mothers and fathers have a rich internal life, but a lot of people feel, “I wish I knew who my mom was as a person, but I will never know.” Although, my mother and father are very good at making that clear to me. (Laughs)

HHK: I definitely relate to that feeling, I don’t come from a family of storytellers, to say the least.

CB: Yeah, so then it sort of creates… they don’t mean to do it this way, but it creates a kind of rupture between you and them, where there is only so much that you reveal about yourself because of that tradition.

And then also another thing started happening, which is that my friends started having kids. My first close friend gave birth about four and a half years ago. They had a baby and literally everything that the baby does, they knew about it. Everything. The baby is having some internal thoughts that you don’t know about and that he doesn’t have a language for, but everything that he actually does is in your physical control. Everyone that the baby knows is someone that you know.

HHK: You are completely controlling his social parameters.

CB: You are completely controlling his life, in a good way!

HHK: And his experiences of intimacy.

CB: Exactly! I was really thinking about that idea of the family as the primary social relationship for people, whether or not you stick with your family that is your primary social relationship.

HHK: We go to make other ones, but not while necessarily giving up on the notion of the family as an intimate unit.

CB: Yes, so that was really important for me. And so I’m interested in exploring intimacy at the scale of family through more concretely visual ways through the film, but also in these abstracted philosophical ways through a piece like Wayfinding. All of the scales of intimacy project tide forwards and backward simultaneously, and Wayfinding really tides forwards. It tides towards a scale of intimacy about engaging a neighborhood, a community, and a site of public space.

HHK: It didn’t occur to me at all when I was at Wayfinding that it had, by design, meant to evoke intimacy with families. But talking to you now, and reflecting on my most intimate experience there, it really was the case for me. Actually, the whole idea for this conversation came about from one of the garden signs at the exhibition. I was going through a particularly difficult patch with my family, my grandmother passed away last fall, and everyone was very wrapped up in their own pain and didn’t have space for other people’s feelings. Right before I went to Wayfinding, my mom and I had a talk for the first time in months, where she said something that made me feel so seen and cared for, and I never got to thank her or express to her how good she had made me feel. Then I saw this sign:

The unparalleled mix of emotions when someone who loves you calls to say: rest I see what you’re doing and the world needs you to be well. Joy, sorrow, and a relief so profound it’s almost bitter.

It completely moved me, and it took me back to that phone call with my mother. I just really desperately wanted to share this with my mother as a thank you that I never got to express that day. I so wished I could just take a photo of it and share it with her, but she speaks little English. I guess the only way to really express what I felt for her, the gratitude and love, I would have to take the time to translate this. And the moment would be lost, maybe. Probably.

[Here is how I translated the sign for my mother:

사랑하는사람이전화해말한다: “쉬렴.

뭘하려는지알아, 그런데세상에정말필요한건네가잘지내는거야,”

그리고그때교차하는이례적인감정들. 기쁨, 슬픔, 그리고한편씁쓸하기도한깊은안도.]

It made me think about the shareability of such experiences, and also the impossibility of it. Across languages, for me, but perhaps otherwise, too.

CB: It’s kind of my contention that almost all emotional shareability is impossible. We pretend that it’s possible when we speak the same language as somebody, but the reality is that when we have these language gaps or barriers—I mean you don’t have a language barrier with your mom, you have a language barrier between my work and your mom. You’re fine with both.

HHK: Right, I’m straddling both imperfectly.

CB: Yeah, but I think actually that is true 100% of the time, regardless. And it’s only in situations where you’re like, “Damn, I have to actively translate this from one language to another,” that it becomes clarified, that this is the kind of work that we have to do all the time. I don’t really believe in empathy.

HHK: I saw that you had said that about empathy in one of your earlier interviews. So that still holds true?

CB: I will now say as an older person than before, this is where I left off, that I believe that empathy as a state is as any other state, so it is neither true nor false. Sorrow, anger, joy— whatever—empathy: they happen. I do not believe that empathy can be more or less understood than any of those other states. Sorrow, anger, joy—whatever. We can identify them. But we don’t totally understand them. And I think the difference is that empathy seems like it can be better understood because it’s relational, and that’s where I am like, “No,” to that. So “yes” to the existence of empathy, but “no” to using empathy as an interpreter or a political motivator because I think that we understand our own internal state so minimally, that it’s almost impossible to be like, now I know how you are feeling. I don’t even know how I am feeling.

HHK: (Laughs) There is something very freeing about admitting that, actually, and yeah, it feels really true. Once again, we started with these cosmic truffles, and for a reason! We are like, please show us anything that will make us be understood! We’re all just begging for categorizations, on so many levels.

CB: So my problem with empathy is I might feel it. With you or whoever else. I just felt quite moved by your account with your mother, I don’t know if that’s empathy or what, but I felt responsive to that. Also, because of the sign that you picked out, the person who said that to me… was my mother.

HHK: Oh, wow… I think I am going to cry.

CB: That’s a real quote, from a real day, that my mom said to me on the phone. And I started weeping. Just like, weeping. And she wasn’t trying to make me cry… She was just being really nice to me. And it totally fucked me up—in a good way.

HHK: Me too, that sign completely fucked me for the rest of the afternoon.

CB: I like those moments when, suddenly, you are totally changed.

HHK: Totally shaken.

CB: I mean, when I think about scales of intimacy, that is what it is. Something that shifts us all at our core together. Just for a second.

HHK: I feel lucky we have the chance to talk about it now and experience some version of it together, right now. Your work functions to create these experiences for the visitors, but how do you translate something so fleeting and ephemeral, like what we just shared together, into documentation or an exhibition?

CB: It’s not so hard for me honestly to make it into a project or an exhibition. But it’s hard for me to do the follow-up translation. Which is the documenting of that exhibition for a further proposal or a website or the Internet, in a way that conveys not just what the product was, but also all the things that had to be translated in order to get to the product. If that makes sense? So that’s what really gets lost when it gets to the documentation of the things I’ve made.

HHK: On that note, I want to speak more about how the concept of translation functions in your work, though I know it’s rarely, or maybe never, between two languages. Your dad is a translator. A Derrida translator no less. [Alan Bass is the translator, from French to English, of Jacques Derrida’s Writing and Difference, among other works.]

How is the role of translation inherited in your work?

Photo Credit: James McAnally. Courtesy of the artist.

CB: Derrida, not at all. Or only through weird osmosis that I couldn’t even begin to describe. But I will say, given that I understand the complexity of that type of work, that translating it from one language to another is impossible, in a way that translating poetry is impossible. Right? It’s totally different frameworks of text, but there is this equal sort of intense specificity and ambiguity simultaneously. And that, to me, is something that I carry over into my work. The idea that between people, at any given time, there is this intense specificity and intense ambiguity, and neither one can be overcome. That is where the site of my main question is.

HHK: The impossible.

CB: The impossible. And I just see that as a social experience. But I do understand it, in part, because of the work that my father does. And the gaps, like what language covers and what it doesn’t cover, is something very obvious to him because he is making these sorts of… It’s not really a one-to-one relationship between them. There are certain things in French that you could say in English translated word for word, but it doesn’t have the same idea.

HHK: He is making creative choices between the two languages.

CB: Yes, and it is a creative act or dialogic act to be translating. So that idea that something is already two things in one—and never there. That’s where my work comes from, I think. Simultaneously, my parents are my parents, and that’s cool, but they are also human beings who are intensely different from one another. So as a kid, I found myself in the role of sometimes translating, even though they both speak English as their native language, between them. Socially, culturally, or emotionally because they are really different. And I sort of understood them both, to some extent. And of course, I can’t say I understood them fully, and they literally do understand each other. There were certain things—my mom would say one thing, and my dad would hear it in this way, and I could be like, “No, no, no, what she meant in the way that you understand is this,” and he would be like “Oh, okay.” That would also happen in reverse.

HHK: How confident were you, as a kid, in being this translator? And in your own translations?

CB: I don’t think I realized I was doing this until I was twenty-five. And then I was like, okay. That’s been my role in the family, that’s what I was doing.

HHK: But you’ve said you’re not interested in transposing one language to another, do you ever think about incorporating other languages into your work to get to your core question?

CB: I am just not fluent enough in other languages. I have adequate Spanish, bad kindergarten German, and some American Sign Language. You know, really shit French. Considering especially that my parents both speak English as their native language, but they also speak French. So I too should speak French? But I do not.

HHK: Well, that is what makes you a true American? As a bilingual speaker, I will say this: when I went to Wayfinding and experiencing various nodes of intimacy that you’ve designed, I was thinking mostly in Korean. I think it’s really interesting to me, how whenever…perhaps it is me remembering, or my body retreating to my first moments of intimacy. At least the first time, I was able to identify the experience of intimacy. In those moments, I retrieve into this native tongue of mine. It is definitely easier for me to express or articulate concepts of intimacy in English, but the experience of it. I start feeling or thinking in Korean.

CB: I love that, and that’s another thing that I’m happy that the work triggered that because, in a way, I obviously don’t know how it feels, but it feels right to me.

HHK: Yes, it feels right, and it makes sense. I don’t know what it means, but that was a definite thing that I noticed and experienced in my walk. The exhibition had tapped me to shift into a different language, and for me, it is a different mode of thinking and being in the world. For example, whenever I feel exhausted by living in English, I kind of shut off and start watching K-dramas and consume a ton of content in Korean. I start reading Korean books, etc. It feels like a rest.

CB: And when my German was better when I was living in Germany. My German was never great, so let’s please not publish that I spoke great German, but it was better. At the end of the day, I was just like, “I can’t with German anymore.” I am so tired. It is exhausting, that act of displacement that happens when you operate in a second language, even if you are completely bilingual.

HHK: Mhmm. At this point for me, it is particularly confusing because obviously, my English is a lot more sophisticated than my Korean, since I was schooled most of my teenage and adult life here. I can do this type of interview with you in English but probably can’t quite in Korean. But with things related to primal emotions or intimacy, I sense myself easing back into my native tongue.

CB: Yeah, so the question that I have emotionally for everybody is, “What is your native tongue?”Internally. And not how we put language to that but what is really true about yourself and the way you relate to others. And I don’t think that’s an answerable question. But it is an interesting kind of thought experiment.

HHK: Yea, I also think Wayfinding is in Harlem, and so the visitors are going to bring different contexts. So many different languages, cultural backgrounds…

CB: And also the way we deal with cities, especially in the context of gentrification, and change, and climate change.

HHK: Oh, God.

CB: I know, are we even gonna go there? Let’s not go there—but we’re going there right now. There will be this other sort of quest for authenticity or truth that we also call history or urban planning or all these other things, but we know that those are produced by power, so “What is this place, really?” is just as unknowable as “Who am I, really?” And that is interesting to me.

HHK: Wayfinding is going to be up for a year, what do you hope it leaves behind? What will it inscribe on the neighborhood?

CB: All of the projects that I’ve done, I think of them as souvenirs for a feeling you haven’t had yet. It’s completed when you have that feeling, and you are reminded of the text or image or gesture or reflection or a moment that you’ve had within the context of this show. That my work allows for a site for memory, not as my work but as an experience that this work allowed for you to have.

The thing about it being there for a year—and that also it will be encountered by people who are planning to see it, but also very much incidentally—is that it has a broader chance of doing that. That having been said, I never get that information back. So, it’s like I am setting myself up for this thing that I don’t receive, I will never know about, but that I kind of know will happen. I have this hunch that it will happen.

HHK: I love what you say about souvenirs, so much of life is trying to relive a memory or hold onto a memory.

CB: Totally. And then there is the neurological reality that every time you re-remember something, your brain is carving it again, so it’s a new neuron. It’s just a new connection.

HHK: Oh, I didn’t know that.

CB: Yeah, it’s crazy. I’ve talked about this before in other aspects of my work, but like it’s never not going to be crazy to me that this is a scientific fact.

HHK: So you are really not recalling an existing node in the brain?

CB: No, you are not. You are doing a new path every time. You think you are remembering something, but you are creating a new path. So you get further and further from the original experience, neurologically speaking. Which is different from emotionally speaking, historically speaking. It’s just kind of interesting to know that’s what is going on in your brain, and I think that about that a lot, too, that like, every time we think we come to understand something, and we name it or call it or we shape it, what we’re actually doing is reinventing it. So everything kind of becomes a moving target in that respect.

HHK: I also wanted to talk briefly about the park as a public place, one of the last remaining true public spaces in America, really, and how it’s increasingly becoming a place of surveillance.

CB: Yes, parts of the audio guide for Wayfinding uses text from the Yelp reviews from the park, verbatim. So, it talks about the police. We also had an incident with the police while we were installing the show. I mean, we didn’t, but the police had an incident in the park while we were also there installing the show, not having to do with us, but we were also there. That’s a terrible way of talking about the problem that I had. Anyways.

But yeah, what is public space anymore, is a very fraught idea. Because public space does not exist equally for all people at any given time.

HHK: Right, it might be a public space for me and you, but it might not be for others.

CB: It is a public space for me, I took a nap in that park. But I also can’t pretend that that’s the experience that everybody could have. And other people sleep in the park for totally different reasons. Not a cozy afternoon 20-minute snooze, not like I-camp-here-at-night-and-this-is-my-home type of sleep.

Public space, too, has become something we think we understand, but it is always kind of never there. In the same way that our internal emotional states, we think they are there, but it’s kind of never there. It’s unreachable, but it’s totally imaginable. It’s part of the common parlance and dictates a lot of our behavior in certain types of way, but it also doesn’t exist.

HHK: Yea, maybe public space is an ideal or a dream we’re wishing is real? As audiences interacting with your show or the Studio Museum’s support for the show is an act of utopic wishing. We are imagining for a moment, or raising a possibility for public intimacy, on a community scale. The concept of creating a public place where people can feel safe enough to navigate their internal landscapes and allow the possibility for intimacy at a park in Harlem. It’s Utopia.

CB: And I am the 99 millionth person to say this, this week, but the underlying linguistic root in utopia is “no place.” It is linguistically true.

HHK: Yes, we are talking about language today, so there you go.

CB: Yes, all the time. All the time.

HHK: I’m still a bit shocked by what you had said about language, how it masks that impossibility, makes us feel like we can actually fully get each other. That we can truly be together.

CB: Totally, and we can’t. And it’s such a lie, and I am not interested in fixing that lie, I am interested in kind of playing within that lie.

HHK: What do you think this lie does for people, why do we hold onto and need to believe in language?

CB: It’s sort of what you sort of came in with, which is smart and true. We need to classify ourselves. We need categories. We need ways of making a big world smaller. And if there is this idea that by speaking the same language we can come to understand each other, that’s a huge relief. Right? We need that kind of relief in order to function.

Unfortunately, I think a lot of people believe the lie. And I don’t believe the lie.

HHK: You very explicitly don’t, which is surprising. Because your work, otherwise, seems so welcoming and all about creating an understanding or connection, on the surface, at least.

CB: It is, but also, I said this recently at an event, but you feel like it’s that. But I never said that any of that stuff is true. I never did, what if I was a really good fiction writer? I am not saying that I am, but I am also not saying I’m not. (Laughs)

But you know the sign that you said that you had wanted to translate for your mother, my mom did really really say that to me, that is true. But just because some of them are totally true, it doesn’t mean they all are. That’s the other thing too, they won’t ever all be fiction because that would also be too predictable.

Chloë Bass: Wayfinding is on view at The Studio Museum in Harlem at St. Nicholas Park in New York, New York, until September 27, 2020.

Helen HY. Kim is a freelance writer and translator between Korean to English. Born in Seoul, South Korea, she moved to the US at the age of 12 and spent her formative years in Los Angeles as a 1.5 generation immigrant before continuing her studies on the East Coast. Kim's practice concerns translation as a mode of life and investigates ways bilingualism shapes artistic and literary experience. She is currently translating a collection of modernist short stories from early twentieth-century Korea.