i.

I don’t recall the first time I saw a tlaquache, an opossum, though I do remember the first memory I carry of one. Tucked inside me, an assemblage of ideas behind my heart, maybe, or just under it, left in that dry dirt, in the weeds of things I do not like to think about but, even with effort, cannot forget. An alley, maybe a monte, an abandoned lot, a room, maybe a shed or a pouch, a field of dark mud, some realm inside us that shoulders our shadows—I think each of us carries such a place.

In the summer, after wanting very badly to, I read the opening to Édouard Louis’s The End of Eddy, and I remembered, then, horribly, while laying in my bed, while cuddling my small hairless dog who died at the end of that summer, I remembered my mother’s boyfriend, and I remembered that small opossum on the fence one night when I was very young, and I remembered the baseball bat, a man’s bulging brown arm, the look of bonecrush and gutcry, the grown man’s full-muscled swings.

In the opening of Louis’s novel, we are told about the boy’s father and we are told about their poverty and their hardships and his queerness growing up in a small French town, and I remember all of this, having identified very much with its shadows, even if my own life came about half a world away. We are told that the boy himself is soft in the ways that boys like us can be soft, and also, we are told the boy’s father is cruel, an attribute, a behavior, a routine proven so early in the novel by the father’s resolution to his problem of the stray cat that stayed near the house having kittens. So early in that story, Louis tells us the father places the stray’s kittens in a plastic bag and slams the bag, the bag with small kittens inside it, against the brick wall. Again, again, he does this. Again, again, he kills them. Until there were no more cries. A resolution, perhaps for the father, ridding himself of these kittens. Yet, resolution for someone often leads to irresolution for another—as it so often plays out, someone’s light is ultimately someone else’s great darkness.

I do not have to tell you my mom’s boyfriend was a real asshole; I do not have to tell you all the shit things he did to my family. But I will tell you that all of the world is stark naked, it is, at some point, when no one or when everyone is watching .

Yes, that night, I saw men kill a tlaquache. Yes, they used a baseball bat. Yes, it was brutal. Those men laughed and they laughed, yes. I was twelve, thirteen, maybe. A strange place, that age, that place of a boy’s life, with the children in the bedroom playing a game and the women around the table laughing and laughing, swallowing their beer, and the men being men in the trees under the streetlights, their long tongues, their sweat, like their stories, building lies of the real men they were and how each, via his tale, held membership in the clan.

Afterward, away from them, behind my mom’s boyfriend’s grey truck parked on the street, when no one was watching, I squatted down to my knees, and holding my fists over my eyes, I imagined what had happened to the small opossum’s body, which lay, then, on the other side of the fence, in an alley, where they’d pitched its battered body when they were done with it. In my throat, my curled heart. In my heart, a heat I’ve encountered only a few other times in my life. Call it rage, call it clarity, call it brownness and queerness. And while I could hear them joking near the barbecue pit, I tried not to think of it, and I promised myself I would grow stronger than them all one day—with my heart in my mouth, I tried not to think of taking a baseball bat to each one of those shitty men.

ii.

I cannot say that I have always loved tlaquaches. They are not like hummingbirds or jaguars—there is no glamor to a tlaquache. Hummingbirds are magical, of course. The fury of their marvelous wings, their iridescent green coats, their red throats. Jaguars, also, with their magnificence, their predatory prowess, their status as warrior symbol, are easy to love or fear, maybe admire, perhaps all of these potencies at once. But tlaquaches are not like hummingbirds or jaguars. Tlaquaches are opossums. They live under our houses, in dilapidated sheds, in great montes, we find their bodies in or the by the sides of roads—they eat ticks, they carry their young on their backs, they lay in the hot sun in the middle of a street or road and die and are run over again and again, if no one picks them up. If they are picked up, frequently, their bodies are frequently trashed. There is no burial, no grief for tlaquaches.

iii.

Behind my heart, or just under it, left in that dry dirt, in the weeds of things I do not like to think about—I am not a good man, I fear. But even not-good men deserve love and want it.

If I say it, will I believe it? If I write it, will you believe me?

iv.

When my husband and I moved in together, he expressed horror over the fact that I knew a tlaquache lived under our house. It is an old house made of wood, with too many rooms, and two fireplaces, one of which is now buried in one of the walls. Since 2008, I’d lived in the house, having left for two years, but returning with my new husband, after my second lover took his life. The house was built in 1925. It is a large house, and true to the time period, it stands atop piers and beams. There is a crawl space, and to access the crawl space, there is a small wooden door on two grey hinges. The door is the size of a large shoebox, maybe one for keeping boots or Stetson hats. Plumbers and electricians have entered the crawl space to perform work underneath the house, and late at night, after walking dogs or upon parking in the driveway, I have seen cats and skunks and tlaquaches using this door. My husband also saw the opossum, one night, pushing its grey body beneath this door, out into the rest of the world. My husband gave it no second thought: he wanted it gone.

v.

The first man I ever loved was not an animal lover. But he loved me, perhaps more than any other human ever has, perhaps more than he loved even himself.

The second man? An animal lover who once, as a boy, rescued a raccoon he called Bandit, and in our time together, also rescued a young blind skunk one dusk, keeping her in one of the bathrooms in our house, and he fed her and cradled her until I convinced him that her best chance lay not with us but with an animal refuge an hour outside of San Antonio. He wept the whole drive home after we dropped her off. He wouldn’t let me console him. Indeed, this man loved animals, more, in fact, than he cared for me, or for himself, or for any other human in the world, except perhaps his mother.

When he doesn’t know I’m watching, the man I love now is so sweet to our new dog that I think my heart will whistle so loud it will give me away. Four years ago, I never thought I’d see the day. Over Thanksgiving, when we lost our pit bull Kimber, I think he wanted to cry, though I never saw him do it if he did. At its worst, sorrow can destroy a man. At its best, sorrow will show us who we are, who we can be.

As for me, I will always be an animalero. Ever since I was a boy. Dogs, cats, owls and other pajaritos, jaguars and ocelots, wolves, coyotes, and armadillos, of course, and, of course, los tlaquaches. But dogs, especially dogs—I feel most at ease when I am home with my family of dogs—I don’t know how else to say this. Perhaps this is my pack, perhaps I, too, simply yearn to belong.

vi.

When you are a boy, you also might have a pack. As part of a pack, you also have the choice to go along with shit or to eschew it. When you are a boy, so often, it is true: the world is yours. When you are a brown boy, the world is and is not yours. A queer boy, too. We are told this in so many, many ways. And so, it is, in fact, routinely easier to go along with racist shit, to laugh at rape jokes, to join in or silently acquiesce as people are ridiculed as faggots or illegals. But these beliefs are not yours. No. None of us owned this shit. Not when we were born, not when our skin first tasted air, not at the moment of our first scream. It was given to us, placed over our bodies like a heavy coat of sticker burrs and tar, forced upon us, even. Eventually, though, we make it ours. We choose. If we don’t molt that tar-burr coat given to us by the world, if we don’t cut away those patches of shit clinging to our hands and our chests, then, we accept those burrs. Accepting them means we are okay with these violences enacted upon others. And often, and tragically, enacting these violences is a way to say we belong, that we are members of the pack. Yes, we choose the kind of boys, the kinds of men we become. Or if, even, we don’t become men at all. At some point in our lives, gradually. All of us. Molting, choosing, tar, chest, power and burrs.

vii.

If I tell you I once believed only good men deserve love, what will I say next? If I tell you this is an old story, a story older than fire and bloodshed, will you believe me?

viii.

Perhaps it is the fact tlaquaches are maligned for their queerness, for that pouch they shouldn’t have or use, for their semblance to other dismissed animals like rats, that we carry aversions to them. “They are so fucking ugly,” someone told me once. “So gross.”

I will not try to explain away others’ disgust for these animals as much as I will try to convey the idea that ugliness is a variable, and the truest discoveries in life also live in the realm of generalizations and variables.

Once, years ago, when I first moved to San Antonio, I bought a camera, and one night sitting on my stoop, I watched a tlaquache make its way out of the alley across my caliche driveway in front of my second truck to the landing below the stairs—a small, square, concrete patch, where I threw food for the stray cats who lived around my house. I watched the little animal eat. I watched it move slowly, watchful and weary at first, and then eat more profoundly, swallowing the morsels as if, in fact, the creature knew pleasure and comfort and wanted joy to last. I tried one night to capture the not-so-small tlaquache with my new camera. I waited by the house. The porchlight dim; my camera on a tripod; my little dog asleep inside. Back then, I did not know much about lighting or shutter speeds and apertures, so when I clicked the trigger, the animal froze and then as I tried to adjust the focus again, the noise startled the animal who took off, leaving its meal behind, abandoning its joy, abandoning it for safety—swiftly, he scurried beneath and then behind my truck and back into the overgrown alley.

ix.

When I was 12, I watched my mom’s boyfriend and his friends beat the shit out of a opossum with a baseball bat. Maybe I was 13. Maybe I was one of them, maybe I am a lie.

x.

And so, it is an old story. Older perhaps than story itself. The boy and the men. The boy and weapons. The boy on the hunt. The boy and the expectations, the duties he will fill. The boy on the farm, in the field. The boy standing before the great sky, the darkness of trees, the wide expanse of his breath, the one inside him, the one he is putting out into the great world. But the boy who isn’t what a boy is supposed to be and be and mean. But the boy who doesn’t want blood on his knuckles–not in his teeth, not on his clothes, not on the ideas that make themselves swirl in his head like a clutch of starlings. Not at all. Nothing like that.

xi.

Like a thread. I heard it one night, as I lay in bed, my arm pressed against my husband’s chest, my arm harboring the soft pull and tug of his lungs—that reminder that something inside him meant there was something also inside of me that moved, even when my eyes shut, when I forgot I was living and fell deeply or not-so-deeply into my sleep. We lay there, my husband and me, and the dogs lay beside us, the big mastiff by my side of the bed, her snoring wakeful and overblown, and beside my husband, on the other side of the room, the boxer mix we’d rescued a few months before, after our pit bull died unexpectedly one night and the house felt emptier than it had in a very long time. Each night now, my husband and I lie like this, and sometimes, the house is as quiet as a thumb; sometimes, it is quieter, a noiselessness that echoes an impossible silence so near the center of San Antonio, the city where we live. But one night, I heard that thread. In the other room, across the hall, that long thin hair of a noise. The boy boxer stood up, and I could see his thick shadow at the doorway, his ears up and opened, and he looked back at me, asking, Do you hear that, too?

Long ago, I feared being the only one awake in the house. I can tell you those reasons, but first I have to explain them to myself.

I think it was the boxer mix, Sweet Baby Ray, the rescue group named him, who first heard the baby tlaquache who’d entered our house. It isn’t hard for me to hear the dogs get up in the middle of the night (when I was a child, I listened for people moving around the house, the trailer, the apartment, at night—perhaps you know what that is like, listening for doom, hoping it wasn’t coming, but knowing well it could, and would, like it had before, come to you, to others you loved, gripping bedsheets like they were your tongue or the wind inside your bones, all the while knowing this wasn’t life but it was yours—and if you know this, then, for that, I am sorry).

And I didn’t know, not at first, that it was, in fact, a small tlaquache who’d somehow made his way down the hall, but he found himself in or led himself, maybe (allowing him more volition), into the laundry room, where I used to feed the small hairless dog we called Tiny, back when he was still alive. (Blind and using only his three good legs, Tiny ate separated from the other, bigger dogs, so that he could eat his fill unbothered, and frequently, he ate to his belly’s content, leaving only a few morsels of kibble in his bowl or beside it.) I imagine when the baby tlaquache tiptoed his way through our house, he’d caught the scent of Iams, and I say this because I don’t know about the capabilities of an opossums’ sense of scent, so I only imagine, like I only can imagine my heart beating with something like a starling—one of them, separated from the rest of the clutch, as they dance, as they move along, as they leave to some place better than before.

I haven’t ever enjoyed being the only one awake in the house, especially not when I was young, but that night with the little tlaquache in the laundry room, I was glad it was only me, as I don’t know exactly how my husband would have taken the sight of the little uninvited animal in our house, holding a morsel of kibble in his two tiny paws, eating and eating and just across from our bedroom.

And soon, I could hear it, too. The sound of teeth breaking into a morsel. Sound of chewing. Sound of a sound I didn’t want to hear while the whole house stood without light.

It took me no time to jump out of bed, and I found it in the laundry room, behind the grey mop bucket, in a corner, near the bowl where the blind hairless dog we called Tiny took his dinner every night. From the laundry room door, the boy boxer stared at the small animal.

I remember thinking, James is going to freak.

I remember Baby Ray looking up at me like, What should I do, dad? Do I get him? Dad, can I?

xii.

Each of us decides, a decision already made before us.

“It’s the way of the world,” a man I met outside a bar told me one

night, seeing my sadness, as we drove to his apartment, my hand in his lap, and a doe, dead on the side of the road.

But is it, really? The world’s way—or ours? Isn’t life what we make of it? I thought, as his big body lay on top of mine, as his breath gnawed at my chest and he asked me to tell him the story of all my tattoos. Easily, I could whisper those stories, all of them, pushing my rosary and spider webs and the name on my neck deep into his chest hair, into his breath made of Listerine and cigars and loneliness, but I couldn’t stop thinking of that deer beside the road. But even with the dead deer on my mind, I let him kiss me, and I couldn’t tell you the rest, as I can barely recall it now, all these years after those facts.

It’s the way the world works, que no?

The forgetting, the dying, the deciding.

Yes, we decide to do with the world or it does with us. What that decision does inside our bodies, in our soft mouths and our even softer lungs, in the small territories of the soft heart and the crawl space underneath its soft meat?

xiii.

Because all of my life, I have been accused of being a man who is too sensitive. Because perhaps I am too full of the milk of human kindness. Because perhaps I wear it in my beard or underneath it, perhaps on my brown skin, inside my tattoos of eagles and praying hands, of saguaro corazones and other men’s names. Because softness is a trait not every man will openly wield. Because there’s a price to wearing softness. Because whomever you are, there is a consequence squatting beside your softness, a declaration, a truth, a pillar of lies, a crack made of river water and salt. Because there’s a cost to letting your maleness fur with its mottles and its marks, its coat made of cariño and mystery and vulnerability and longing and suffering, joy. Because softness is not muted, and softness screams its name as if the name was bone and dry soil and all the unwanted and wished-dead things moved by wind. Because a body is never just a body. Because softness is the body, but softness is also the breath of holiness inside each of us, which is love of life, which is an awareness that people and things outside of ourselves do matter, which means connectedness, and which, if you are like me, means God.

xiv.

As I flipped on the laundry room light, I worried the boy boxer might go for the creature, having already killed an opossum on our patio one night.

(A small thing, I found her near the steps, her fur damp and matted and slobbery from where my dog had taken her small body into his mouth. So tiny, like a kitten, I recall thinking as I picked up her limp figure and set her on a white cotton towel in a box. I remembered the dog’s mouth frothy, a foam formed around his muzzle. And I’d like, now, to think he didn’t know what he was doing, that in him there isn’t a killswitch, a blood-hunger waiting to ignite, some inherent tendency that propelled him to take her small body into his teeth, squeeze down, and shake, but perhaps that absence of instinct is even more terrifying. As much as I say I am an animalero, there is so much about the animals around me I don’t know. I suppose on most days I am okay living without touching their secrets. With heaviness in my mouth, I set the little tlaquache’s box by a tree in the front yard, and I stepped away, hoping the idea of living was more than an abstraction, that it had more traction than a sigh, more mass than the simplest of all hopes. In the morning, she had stiffened. I’d feared this likelihood like a tree branch, like a gust, like a hole underneath our house, whispered. And while I had hoped really to find an empty box, I walked out into the yard wearing only my sleeping shorts and stoicism. I’d locked the dogs in the house. Whining that they wanted out, the two big dogs watched. And I stood beside the tree, holding my own hands, looking at lifelessness, at consequence, at her.)

With the small tlaquache eating kibble in front of our washing machine, I put the boy dog in the bedroom and shut the door, and this woke my husband, so I told him, “Keep Baby Boy inside. There’s something in the house.” I tried first with a wicker basket to corral the small opossum, and I also had a towel to throw over him, an approach I learned from my second lover when he rescued a skunk—if you cover them in darkness, they might not fight you.

But the small opossum, with its small opposable thumbs, quickly made his way out of the braided container, and before I could get the bath towel around him, he rushed down the hall, under a door to one of the spare bedrooms, and under the closet door.

Opening the closet door, trying to grab the baby opossum with the towel, he hissed, and at this point, I had to ask my husband for help. The small guy shit himself in the closet, the fear on his body; I don’t know if opossums can see possibilities, potentialities, but I know that he saw me and he saw my bigger hands and my husband standing behind me, holding a flashlight. I don’t need to imagine his terror. I can still hear him hissing.

In the end, we used a red plastic bucket, and I walked the little guy outside, as the boy boxer stood at the side door wanting to follow me. I imagine those moments in that bucket—the small opossum may have lived panic and perhaps confusion, a feeling of being trapped. Perhaps, too, he understood danger, clawing against the red sides, sliding down, unable to grab hold of anything that might lead to a way out.

That night, I let him go near a tree in my front yard.

xv.

I’ve known this for a very long time: Some of us let monsters into our houses. If they come, we let them stay. Sometimes, they knock. They might wear politeness and civility on their faces. Maybe they place themselves in our lives strategically, grooming us, grooming out our distrust, giving themselves good light. Our mothers let them in, our fathers, too. And if your mother or father or grandfather or some other family member is that monster, does that mean God let them in? Eventually, when we begin to see what or who they are, we may try to send them out, but they come back, even if we block entrances with sofas and books, even if we nail shut all the windows and doors, lock them with muscles and prayer, even if we agree not to tell another living soul.

xvi.

Even shame is a weapon when wielded as such. Which proves that anything can be weaponized. Which proves that anything can be carried around in a pouch, taken out. Anything can be made to bleed.

xvii.

But there is another story, too. An old story. Old, too, like that other story. The story of a boy who does it. The boy who doesn’t walk away. The boy with blood on his hands. The boys who kills. Knuckles, whole fists, measured-and-unmeasured hands that did what boy-hands and boy-bodies are, indeed, told to do. And, after the fact, he might look back, and he might miss home or know wrongness, because he accepts indifference is an indictment of godlessness. This is an old story, too. And this is a long walk home, the long arms, or the short ones, hanging beside the boy’s body, dripping with the abstractions of guilt, of confusion, of new consciousness and shifting, dripping with despair, because it is, indeed, a painful thing to live with one’s blood deeds. It is a painful thing to walk away from the boys we are supposed to be. Violence will haunt a boy even when he forgets it’s there.

xviii.

And I’m going to tell you another story. This is the story of how I am not good. This is the story of contradictions and walls. A story of bricks and opossum bones. This is the story of failing, which is the story, then, of what kind of man I have become and how. Early in my life, I decided that while I didn’t know what type of man I would be, I knew the type of man I would not be: vicious, cruel, spiteful, unaware. I wanted to be kind. I wanted to carry compassion in my hands like a kite. The feathers, the talons, the long-sharp beak and eyes. Really, all my life, I have just wanted to be good. Really, all my life, I have worried that I was not good.

xix.

You see, there was an opossum living under our house several years ago. This bothered my husband, and he wanted him out. To appease my husband, I read about ways to distance a tlaquache from the place he or she calls home, which happened, also, simultaneously, to be our home, the one my husband and I moved into that summer when I told my body it was alright to love him.

I tried sprinkling cayenne pepper around the crawl space door, red powder staining the concrete. I tried running my dogs around the house, after reading online that dogs’ scents can dissuade opossums and skunks, although I’d already tried the cayenne pepper, which seemed to only dissuade the dogs. So then I tried dipping rags in dog urine, which seemed implausible at first, given that my dogs piss in the grass and the earth being the earth does what it does, however, by this point Tiny, the small hairless, had begun eschewing the grass for his business, opting instead for the concrete. It was easier, then, to soak rags in puddles of Tiny’s dark yellow piss and lay them out by the entrance to the crawl space. But I admit, as much as I wanted each of these tactics to work, as much as I would have taken any of these solutions, each of them flopped. The opossum would not give up his home, or hers, which also was mine and James’s.

When I admitted I’d failed, James suggested we block the entrance.

“We can’t trap him in there,” I said, after a few moments, judging my own words, harnessing them and not wanting the words that the heaviness in my mouth made to grow sharp or fling out like the jaggedness that was happening inside me.

In certain ways, I was dispirited by the idea of making the opossum leave. And while I didn’t expect to fully convince my husband of the benefits of keeping a tlaquache around, I did my best to promote the idea that opossums eat ticks and other bugs and even, I’ve heard, run off rats. There is nothing deliberate, though, about not wanting to force a creature out of its home—and I say this fully aware that it was because, and only because, it was a tlaquache that I felt guilt wad up inside me like a hive, exterminating any rat I would have said fine to.

But didn’t I say all creatures want love? And deserve it?

But didn’t I say I wanted to be a good man? Kind and not cruel, conscious of my hands?

xx.

Then, too, there is the origin of opossum. The word comes from the early 17th century—from Virginia Algonquian opassom, from op, ‘white,’ and assom, ‘dog.’

If my grandmother from Coahuila were still alive today, I might ask her what she knew of the word tlaquache. She would hold her long braid, the ends of its grayness, and she’d hold out her hand, which was a reminder of what happens to brownness when it’s old, and she might tell me what I already know, which is the word itself is brown, browner than me, brown like aguacate like Tenochtitlan brown like xoloitzcuintlis and tierra and time.

So maybe it’s the brownness of the animal I love. So maybe it’s the likeness to dogs. Or maybe it’s the story. In other words, maybe it’s the guilt I will

forever carry when I watched and did nothing as my mom’s boyfriend and his friends beat the shit out of an opossum with a baseball bat.

xxi.

Someone, right now, is thinking, It’s just a fucking opossum. Just. Just.

xxii.

Someone, one time, said, They’re just queers and hookers and junkies. Just.

xxiii.

At this point in my life, I do think my mother’s second husband hated me, because he knew I was queer. Do I need to prove it? Of course not. Not my queerness, not his hatred. What’s there to document?

I know he hated people like me.

My mother knew he hated people like me. She told us. I think back then my mother knew I was queer, also.

Back then, I think my mother hated us too.

And so, what becomes of one’s body when two truths inside you face off? When two things you know to be true, on a collision course, bare their teeth and glare? Who wins? Who do you help? What side do you pick, if not your own?

My mother was lonely. She was lonely for a man.

Perhaps you know that kind of loneliness. I know that in the middle of my years, I do. And so I can understand, now more than halfway through my own life, that sometimes the body will do what it has to do to not be lonely.

But hurt is hurt, and hurt is one of those elements like a rock standing in a yellowing field or a tree branch that’s broken off but hangs, still, unable to fully separate from the rest of the tree: joto. Joto.

Joto, if you can hear the bones breaking in another human’s mouth, then, you understand, like I understand, like we understand— there is no need to prove shit. No need to pick up the stone smeared with shit and hold it up to the light so others will believe its truth, there in the lines of your palm. No need to climb the broken tree and point to the hinge, no need to grab the splinters, that juncture where togetherness ended its hold on the tree and the forces at work set in.

It’s not that hard to know when people hate us.

And after the fact, what else is there to write down or photograph or sing of except the simplicity of hate. He found me ugly. I reminded him of something or someone from who he was before, and he wanted me gone.

I don’t need to tell you my mom’s second boyfriend, who later became her husband, ran me off. I was twelve, maybe thirteen. He did it with beatings and insults, by killing that opossum, and by wishing me not there, which is the way men often do.

There are stories I am not going to tell you. In any case, we begin to learn this tenet early on in life if we are watching: if we see something as ugly or unworthy, as lesser, then it is easy to allow it to be thrown away, to be uprooted and removed, to be smashed with baseball bats and condemnations, whole fists, silences and vitriol, lies and laws, ultimately destroyed.

We begin by watching others do it, hearing it transpire in our houses, on playgrounds, in locker rooms, when no one is looking and also in full plain sight of those who might put a halt to the torture. And one day, one day, we do it ourselves.

xxiv.

I am willing to concede that none of us is as innocent as we’d like to be.

I am willing to concede that I have hurt other things, other people.

I am willing to concede that there is a luxury and privilege to the act of washing blood from our hands.

Yet, I am not willing to concede the pain of this story. In this sense, I am a man. In this sense, we will always be those boys.

xxv.

In the end, I will tell you that one night, after the gym, my husband and I drove up to our house to find the opossum, just leaving the crawl space, illuminated in the driveway by the headlights of our red Ford. The animal scampered, climbing over our small retaining wall, into the neighbors’ dark grass.

James did it quickly. In minutes, he’d walked in darkness back behind the wooden shed, emerging with a few bricks, his hands gripping the stone as if stone itself could be both resolution and broken promise. On a night with the summer overwhelming the air, my husband stacked the bricks in front of the crawl space, and I went into the house to tend to the dogs, to give them their food and cariño, to refill their water. In moments, my husband entered the house—he had blocked the entrance.

What’s done was done, and we went to bed, after eating, after watching the late news, and in the morning, we made love, and I made breakfast and I kissed him goodbye before going to work. I figured the little tlaquache would have to find another home. It’s just the way things worked, in life, in this life I was making.

But the truth is we didn’t know that there was another opossum, thinking that only one of them lived under our house. What happened next is a damn spot on my hands, proof that I have stopped begging stars to hide their fires.

Perhaps I am only making excuses for myself, as men often do. Perhaps I am trying to defend what James and I did, or redefine it, as men often do. But there’s no way I could have known another opossum was living beneath our house when we shut off the entrance to the crawl space. Admitting that is fine, though it does nothing to alter the fact there are bones trapped somewhere in the walls of our house.

xxvi.

When the exterminator came, it was because the smell of something dead had permeated half the house. The front half: the living room and the office and the kitchen, the hall by the mantle, the fireplace, and one of the bedrooms. The man wore a blue suit, which he put on, over his clothes, to go under the house. As he crawled under my house, I stared at the inside of the crawl space door—there were scratch marks embedded in the wood, snagged on the splinters there was fur. There before me was what I, what we, had done.

After fifteen or so minutes, the man in the blue suit who was supposed to find the dead thing emerged, although he’d found nothing, except a hole underneath the house, he said, near the big fireplace, that led up into one of the walls.

“We can punch out the walls. To find it,” he said.

I asked, “How will you find it?” “We’ll just have to start breaking through walls. We could find it the first time. Or we could go through all the walls.”

Somewhere a tlaquache had died in our house. I thought of that desperation, of trying to escape a house that wouldn’t let you out. When he, or she, died, what was I doing? Was I lying on the floor, playing with my dogs, whispering sweetnesses to them, stroking their long necks or their bellies? Was I reading the book I was rereading at the time, Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red, or writing some draft of a shitty poem I was trying to make good? For all I knew, James and I were opening each other up as the small animal took its last breaths, as it suffered and struggled and finally surrendered to death. For all I knew, I was feeling sorry for myself or looking at the parts of my body I don’t like in a mirror when it died. I don’t know. I don’t.

In the end, we did not punch through the walls.

“It will go away after a few days. Three or four of them,” the man in the blue suit who’d been under my house said.

As a result, I hung bags of charcoal in all of the rooms. On doorknobs and in closets I hung coal. I found them at Lowe’s, near the rat traps and/or the air filters, I can’t remember exactly. I sprayed aerosols, but the combination of rot and cinnamon fucked with my head. Even tobacco leaf candles and boiling orange rind did little to quell the air. And for a few days I watched the dogs sniff urgently at the house. The mastiff sometimes pawed at the floor, and I wondered if there were other things living under my house, trying to get out. Every so often, I caught a whiff, and in time, I removed the bricks and let the door again be moved.

xxvii.

But hurt is hurt, and we each carry it around. Some days, we pass

it off or around; and too often we aren’t even aware that we’re pushing our hurt off onto someone, asking or telling and perhaps, tragically, even forcing someone else to carry it.

xxviii.

Splinters and lightning and the echoes of things that, over all of these years, have stuck to our skin and our bones and our hair— alley or monte or room or field, crawl space, or inside the walls of us, maybe a red bucket, maybe a box, maybe a backyard under a streetlamp by a fence, maybe a pouch that has grown inside us. The world is what we make of it, que no?

xxix.

The truth is I was glad when my mother’s second husband left

her. Or when she left him (even all these years later, I don’t know which version of the story is truer). I understand now that to him, like to millions of others, my queerness, our queerness is monstrous and therein must be displaced, interrupted, destroyed.

In Carson’s book, Heracles loves the monster Geryon. Or more accurately the other way around—the monster Geryon loves Heracles, who is cruel, who will be the monster’s good death, his pain, his one volcanic memory.

I admit there are times in my life when I pursued monsters, when I loved them and thought I could save them. From themselves, from the world, from me.

All creatures want love. I believe that. I will say it. Again and again.

I don’t think tlaquaches are monstrous at all. I am enamored with images of mama tlaquaches carrying pups atop their backs, traveling, taking them all. I am enamored with the idea of the pouch they are not supposed to have. Or we.

To someone, right now, I am monstrous for what I just said, for what my husband and I unknowingly and knowingly did to the tlaquache beneath our house. Some days I can be washing dishes or sweeping up the dog hair, and I remember there are tlaquache bones embedded somewhere in our walls, and then, I believe I am monstrous.

To someone, when I hold my husband tonight, when we lay in our bed and I turn off the lights and I press my brownness against his body, that will be especially monstrous. (I hope you and your loved one(s) are partaking in that monstrosity too.)

The pockets of men are monstrous, also, to some. The pockets of women are monstrous to others. The pockets of those of us who are they—their pockets, also, especially, now, in these times, are seen as monstrous by some and are under attack.

It’s not that hard for others to know when we hate them. It’s not that hard to know when we are hated, or when we hate ourselves.

But even monsters can be missed; even the monstrous can be yearned for.

I suppose some days I have to remind myself that all creatures deserve love, deserve affection—including myself, including the parts of me and the memories I don’t love. I suppose sometimes I have to remind myself that all of the world is stark naked, it is, at some point, when no one or when everyone is watching what we do.

[separator type=”thick”]

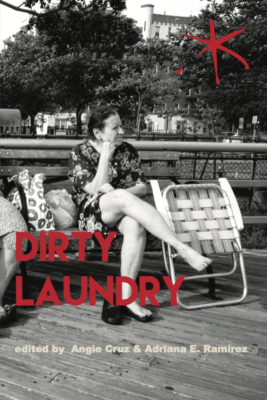

Read the print version of this essay in our FALL 2017: Dirty Laundry Issue.

Joe Jiménez is the author of The Possibilities of Mud (Korima 2014) and Bloodline (Arte Público 2016). Jiménez is the recipient of the 2016 Letras Latinas/Red Hen Press Poetry Prize. Jimenez’s essays and poems have appeared in The Adroit Journal, Iron Horse, RHINO, Bat City, and Waxwing, and on the PBS NewsHour and Lambda Literary sites. Jimenez was recently awarded a Lucas Artists Literary Artists Fellowship from 2017-2020. He lives in San Antonio, Texas, and is a member of the Macondo Writing Workshops. For more information, visit joejimenez.net