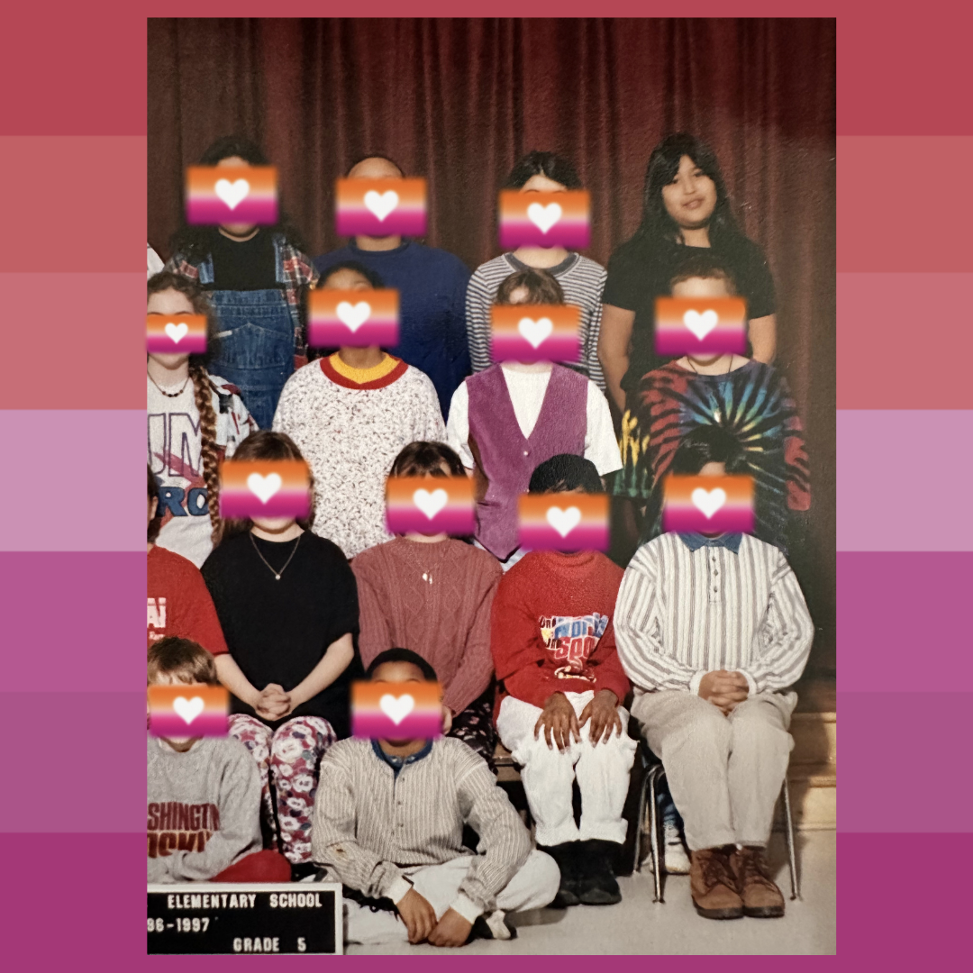

I was christened a lesbian when I was ten years old. My two best friends in fifth grade were the priestess who overlooked my early baptism; they immersed me in a circular pool with jeers and laughter.

The memory returns to me when my wife and I realize our son might attend my old elementary school. But the memory returns not at the mention of my old school, but when my wife leans in to kiss me.

When I close my eyes to receive the touch of her lips I identify a twinge of shame that didn’t feel present between us before the rediscovery of this memory. Shame drops into my stomach like a heavy rock. I hear the laughter echoing, I feel the rippled dents of the beige-colored concrete walls. I want to melt into those walls and disappear. The knot in my throat tightens but I do not let the tears flow.

My lesbian baptism happened on a Monday. I hid back tears behind my misshapen bangs. I tried joining in on the laughter too, as if I was in on a big staged joke. I pretended it was someone else we were laughing at and taunting. I was good at being quiet, at blending in. Good at going with what the other kids said and did. Good at making myself the joke. Good at hiding. Staying quiet and hidden was essential to surviving school, especially if you were a brown, chubby, anxious and awkward little girl. That combination was unforgiving.

It was the backing away as if I had shit my pants, the finger-pointing, and the hollering from a circle of kids with me in the middle, that clued me into the fact that there was something wrong about being called a lesbian. I stood in that circle of taunts laughing at myself hoping to hide in plain sight because I had no idea what I was being called or why. I was hoping this term somehow meant something that was easy to fix, like being called stinky. If I was the stinky kid, I could just go home, lock myself in the bathroom for over an hour and finally run to my Mami’s room to steal her perfume. I could spray her Estée Lauder Beautiful, that she only ever sprayed for very special occasions, all over and never be called stinky again. Being enfolded in the flumes on a perfume only used by older white women could have become my resolution.

But it was the months that followed after being called a lesbian in the fifth grade, that made me understand it wasn’t something I could fix. All the Estée Lauder Beautiful in the world wouldn’t save me from being the fifth grade lesbian. I became permanently and indefinitely marked for the rest of the year. No one talked to me anymore. No one played with me and if a ball would happen to roll anywhere near me, that ball immediately ceased to exist too. Being called a lesbian became something that destroyed my early friendships with other girls too. It planted a tiny seed of shame I’d buried deep inside my esophagus that would slowly start to grow as I came into myself and learned that this thing I was called so early on was true all along. What I had missed is that seed became a sleeping volcano.

That was 30-something years ago and I have never returned to this memory. Now, it haunts me. It sits with me begging my mind to replay that singular memory over and over like some cringe holiday movie on a network channel no one is watching. With each play, the opening credits appear in bold white over a black background: “I know why you didn’t sleepover. It’s because you’re a lesbian…..”

How was I discovered so early?

How was it that they knew before I even knew?

Was it something I said or did?

Did I do something wrong?

This is what haunts me. The shame, I can feel it boiling.

*****

My best friend Wendy was celebrating her 11th birthday with a sleepover. We had talked about it for weeks. The plan: we’d stay up late watching TV until we knew her parents were asleep. We’d have a pillow fight. We’d make prank calls to random numbers listed in the thick phonebook with thin pages. We’d prank our own houses too. I imagined how the entire evening would play out. I didn’t know this then but when I’m in my early 30s I’ll learn about how some people actively try to imagine different scenarios in order to find relief from an obsessive fear. This makes sense as to why the evening ended the way it did for me.

But here’s what I imagined the sleepover to be like then: one of us would dial and say into the receiver, “Is your refrigerator running?” We would quietly wait for a “yes” and bust out “well you better go out and catch it!”.

We’d laugh well into the night and just like in the movies, it would end with us whispering our secrets and vowing to be best friends forever. That vow excited me most; I was desperate for friends and eager for another girl to call me her best friend.

I especially wanted that with Sonya.

Sonya was Wendy’s second-in-command. But there was nothing “second” about her. She was special. Sonya knew the corniest yo mama jokes and would obliterate our mothers. Her laugh was infectious. A laugh that started as a small snicker and grew into a roaring belly laugh with snorts making it so that even when her jokes weren’t funny, her laughter was enough to get us all cackling like a pack of hyenas. Next to me, Sonya was slightly shorter with a perfect black bob-shaped hairstyle that fell around her cheeks and just above her shoulders. Sonya’s laughter might have been infectious but it was her smile that was captivating. She had two front teeth that were slightly bigger than the rest but when she smiled her full lips that naturally puckered hid them so her smile resembled any model in a colgate commercial. She was perfect.

Sonya disarmed the boys. She demanded space and challenged them. She didn’t know how to play basketball but she’d still step into their games by stealing their ball and bulldozing her way into them to take a shot. A shot she would end up missing every single time. Her energy brought the boys in and we’d giggled anytime one of them tried to come over and talk to her afterwards. She wasn’t interested in talking to them, she only wanted to mess with them. She used to tell us her older sister would say to never let a boy think you like him, instead show him you don’t care.

But the thing that made Sonya so special to me wasn’t necessarily that energy. It was the fact that when it was just us, she’d hold my hand as we walked down the hallways. Sonya loved hugs and she’d wrap herself around me in a tight embrace after every hello and goodbye. Between Sonya and I physical space didn’t exist. Before Sonya, I had never experienced that level of physical affection with another girl. We were tight. We were close. So close, we shared jawbreakers the size of baseballs. We’d take turns licking the colorful orbs; we’d watch each other lick the jawbreaker until it got small enough to fit in our mouths. We were convinced we’d find something special in the core.

So I was convinced that Wendy’s sleepover would seal our friendship forever.

There was one small problem–I had never slept over at anyone else’s home before. It wasn’t that there weren’t opportunities to attend sleepovers that kept me a sleepover virgin. And it was easy to place the blame on my strict Mexican parents. Often, I’d lie to my primas when they’d beg me to ask for permission. It was an easy lie to tell: though Mami caved to my adorable prima’s pleas sometimes, but Papi would remain tight-lipped. His silence meant it was a “no” and my Mami never fought it. That’s how I remained a sleepover virgin for years.

I was the problem. I couldn’t handle the idea of staying in a stranger’s house. That was the epidermis layer of it. The dermis layers, hidden deeply underneath, held my secret fear of the darkness; specifically the darkness that penetrated a home. I didn’t exactly fear the idea of the dark, I feared what could happen in that darkness. My experiences so far in the darkness had taught me that it twisted people into something else. In the darkness, a doorknob of a locked room would feverishly jiggle for minutes that felt like hours before stopping completely. In the darkness, a little girl would be bolted out of sleep in a deep panic by the wrestling of the doorknob. In the darkness, a little girl would try to recite prayers to a God she learned wasn’t listening. I couldn’t let anyone else see that I was that little girl. I wasn’t willing to share the secret of why the darkness had groomed me into these robotic reactions.

Not Wendy but especially not Sonya.

But I feared being friendless and alone more than I feared the darkness and my secrets. So I gathered the courage and said to my parent’s “It’s one night. Everyone in school does it all the time.” When that didn’t work, I reminded them of every single time my primas would ask if I could sleep over their house and they wouldn’t let me. I parroted Mami’s older brother’s pleas on behalf of his daughters back to them “déjalas que sean niñas”. I demanded that they let me be a girl just this one time and then to finish my argument completely I hit them with a gut punch I had learned never to use – “you guys just don’t understand that this isn’t Mexico”. And that did it. Their mini translator and navigator between languages and cultures calling them out like that was enough to finally make them say “esta bien”. .

******

There was a lot riding on this sleepover. Before Wendy and Sonya, there was Yasmin. Yasmin taught me the power a girl could hold over another girl. Fear. Fear became the power with which she kept me close. I met Yasmin in my Tia C’s child care business. She ran it out of my godmother’s house. It was packed with family, neighborhood kids, and children of other immigrant families our parents befriended. Tia C would watch more than ten of us. Different kids always coming in and out, it was all very Lord-of-the-fly-ish.

I was in the second grade when Yasmin appeared at my Tia C’s door with her loud Mami. Yasmin was much older and having recently migrated from Mexico, she was held a few grades back since she struggled with English.

Yasmin overpowered everyone at Tia C’s but she took a special interest in me. We fell into a pattern. Anything Yasmin said to do, I would do. I became Yasmin’s hands. When she said we needed to beat up another girl, I hit that girl over and over again even when she curled her body into herself on the floor. I didn’t stop until Tia C stopped us. The girl had done nothing to me. But Yasmin said to hit her, so I hit her.

One day, Yasmin called me into the bathroom at Tia C’s. She locked the door behind me and pointed to the toilet water. It was bright pink with thick clots of burgundy and black sprinkled on the top. Her period.

“Si no lo miras, te lo unto. ¡Míralo!”, she said. I stared at the toilet bowl for as long as she needed me to, so she wouldn’t smear the blood all over me. Yasmin laughed when she saw the fear in my eyes. It wasn’t until I started crying that she’d finally open the door and run out.

This became her abusive and sorted version of a friendship pact with me. A ritual she’d perform to keep me in line. It was the only type of friendship I knew. A friendship driven and held together by fear. A friendship in which I’m a pawn to a queen. But even that friendship ended.

One day we bumped into each other in the bathroom. Not at Tia C’s, but at school. The sight of her in the school’s bathroom filled me with so much terror. The anticipation of seeing her blood pool burgundy and black made me wet my pants. I stood in front of her, my pants soaked with urine, dripping slowly onto the bathroom floor.

She yelled “¡cochina! Te measte” and ran out of the school bathroom so that no one would see her with a girl who wet her pants. Not even all the previous months of being secretly subjected to her period, made out to be her pawn ready to protect the queen, was enough to be seen with someone like me. So the sleepover became my chance at redemption. The chance not only at real friendship but the chance to prove there wasn’t anything wrong with me.

*****

For the sleepover, my parents bought me a brand new lavender sleeping bag with small printed white flowers. Why did I need a sleeping bag if I could take with me the huge cobijas with an eagle on it? My parents asked. “We’re sleeping on the floor”, I said. They didn’t get it. We left Mexico so I could sleep on a real plush mattress, not on the ground and this became my reminder to them of why it was important I have this quintessential “American” experience.

As the sleepover day approached, Mami still wasn’t convinced. Her doubts should have been a sign for me. “Estas segura”, “Vas estar en casa ajena” and “Que pasa si te da miedo?”, she’d ask the week before the sleepover. But I had facts prepared to fire back:

1. La Wendy’s house was five minutes away. If needed, I could walk home.

2. La Wendy’s mom was nice. She always popped out with a big smile and waved at the school bus driver.

Then there was the last and most important reason:

3. “Va ir La Sonya, Mami” I’d say to her with pleading eyes.

Mami had met Wendy and Sonya a couple of times when they’d come over after school. She’d understood we became close like a pod of dolphins. But Mami never had much to say about them. She would disappear whenever they’d come over. She didn’t ask questions about them or about any other friendships I had in school.

It was my Mami who dropped me off at Wendy’s. I had to talk her into coming to the door instead of leaving me to walk up on my own. Mami avoided talking to other parents, afraid to fumble the few words she knew in English. I got used to sensing her embarrassment, always ready to step in and pick up the conversation. At drop-off, my Mami said a quick “hello” and “thank you” before giving me the typical pórtate-bien-estás-en casa-ajena look.

Wendy and Sonya rushed to greet me at the door with Wendy’s cousins and sisters in tow. I wave goodbye to my Mami and get rushed into running upstairs to Wendy’s room while Wendy’s mother yells behind us “Girls we are going to be making our pizzas soon so be back down here in five minutes”.

I’m back there, a fifth-grader, in Wendy’s bedroom.

I am frozen with reality sinking in. Her room is nothing like my room. There is no nightlight. The wood-paneled walls make the room darker. The room will turn pitch dark when the lights turn off.

Everyone sets up their sleeping bags. Sonya rushes to take my hand. “Sleep next to me,” she says as she guides me to a spot by the door next to her sleeping bag. I feel a rush of warmth. I sense Wendy watching us from her bed. “Girls, come down for pizza”, Wendy’s mom yells.

We make pizzas and sing Happy Birthday. It’s almost time for the sleepover part. My heart thumps a little harder.

Wendy’s mom saying, “Alright girls lights will go off in ten minutes. Get dressed and ready for bed.” causes my heart to thump harder. In the bathroom, my mind won’t quiet down as I slide into my PJs: What about the pillow fight? Watching TV late into the night? I had rehearsed the entire night in my mind for days, there was supposed to be more time, more activities to make it so we didn’t all lay in the darkness together so quickly. It wasn’t supposed to go this way. The darkness wasn’t supposed to be coming so quickly. My eyes meet Sonya’s as I step out of the bathroom. She smiles. My heart settles.

As long as Sonya is sleeping next to me, I can do this.

“Why aren’t you sleeping next to me, Sonya?” Wendy asks as she approaches once we have settled into our bags. “It’s my birthday. She pees on herself.” Wendy points her finger at me.

“You don’t want to sleep next to her,” Wendy and Sonya both laugh. I try to laugh too but my face goes hot.

I lower my eyes and mumble “That’s not true.” Even if it was true. But how could she have known? She didn’t know Yasmin.

Sonya looks at me and then at Wendy and says “I wasn’t going to sleep next to her. She tried to get me to. Did you see her grab my hand? There’s something weird about her.” I can feel a knot form in my throat. It’s the knot that usually shows up when I am about to cry.

But Sonya was the one that grabbed my hand. Sonya’s the one that reaches to hug me at school . Why is it weird now?? Was it wrong of me to imagine that perhaps during the sleep over, her warm body next to me, might help fight off any fears the darkness might pop out? Was it wrong or weird of me to hope that maybe during the night she might reach for me like she does at school before we both fell asleep?. Was it wrong to hope or imagine she would do that sometime during the night after we whispered our secrets to each other? I wanted this all to end up with us being best friends forever which I thought might be sealed by her sharing something with me she’s never told anyone before. None of the night was supposed to go like this. When the lights go off, I curl next to the door. Alone. Sonya moves her sleeping bag next to Wendy’s bed. I can hear them whispering. I try hard not to cry but the tears come in hot.

The darkness is here. The whispering is just loud enough for me to make out what is being said. Wendy and Sonya are talking about me. Sonya is telling Wendy about the times she’s hugged me and how weird I made it. Sonya’s telling her that when she hugs me, I hug her back too tightly. That I make her hold hands with me and she thinks I might be “obsessed with her or something”. They both agree I’m weird and that it was a mistake to invite me. The other girls start to chime in but I’ve tuned them all out because I can feel the darkness starting to claim its rights to my body again because of the whispering.

My heart is thumping faster and faster in my chest, hard like a jackhammer. The panic that the darkness brings, has found its way in the room with us. The darkness has done it again, turned people that I thought I was safe with into something else. The darkness has willed them against me. With this panic comes a flood of thoughts,what if I pee myself in my sleep? Sonya thinks I’m weird. Why am I weird? There’s something wrong with me. I’m not normal. I ruined this. I ruin everything. The harder I try not to cry, the harder the tears come.

I grab my sleeping bag and push myself out of the dark room and into the lit hallway straight down the stairs.

When Wendy’s Mom sees me, she throws questions at me like bullets “Are you okay? Did the girls hurt you? What’s wrong?”

In the light, I settle down enough and say, “ I want to go home.”

Mami picks up the phone on the second ring. My crying picks up again as Wendy, Sonya, and the girls all watch me from the stairs. My Mami shows up 15 minutes later. Still crying, I pick up my sleeping bag and head out the door. Mami hangs back and mumbles quiet sorries to Wendy’s Mom and the girls.

In the car ride home, Mami doesn’t say a thing. She doesn’t scold me or ask me what happened. She doesn’t even give me her typical “ya ves” which she reserves for moments like this because she turned out to be right. In the years to come, that evening along with a handful of other failed sleepover attempts, will turn into a running joke between us. “Mi niña nunca pudo dormir en casa ajena porque extrañaba mucho a su Mami”, she’ll say. And I will laugh and lean in to hug her to reassure her the reason I failed those sleepovers was simply because I missed her too much and not because of anything else.

But that night after returning to my own bed, I let the darkness continue its claim to my body. The panic backed out of my chest and settled into a whirlpool of thoughts in my mind. I stayed up all night hugging my teddy bear and thinking about Sonya. Replaying every hug she’s ever given me. Every instance when she’s been nice to me. Hoping that when Monday comes, no one will have remembered the sleepover.

*****

“Stop. Don’t come any closer to me. I know why you didn’t sleepover. It’s because you’re a lesbian.” It was Sonya who christened me first, that following Monday in the hallway while we waited for the cafeteria to open.

“That’s why you left the sleepover. You like me.”

It’s the first thing Sonya says to me as I approach her and Wendy outside of the classroom. I found them leaning into each other whispering about something. I was hoping they were whispering something about the teacher or another kid, like we normally do while waiting for lunch to start. I thought we could pretend the sleepover never happened.

But Sonya and Wendy stand in front of me, suddenly taller than I remember them. Sonya’s smile fades from her face and turns into a smirk. I know that smirk very well. It’s the smirk she makes when she’s getting ready to make fun of someone. Sometimes the other kids will think it means she’s just joking or smiling but this smirk is not her smile. It’s not the smile that fills me with warmth watching the way her lips part and cheeks expand up. This smirk fills me with fear. With furrowed eyebrows, Sonya stares into me and closes the space between us as she says it louder this time:

“You like me, you lesbian!”

“You tried to hold Sonya’s hand at my house in the dark. I saw it!” Wendy chimes in.

Suddenly, I’m surrounded by snickers that break out into “Ohs” and “Ahs” and “That’s so gross, man.” Everyone backs away from me quickly yelling out “no one touch her”, seconds before the cafeteria doors open. This is the moment I’ve been marked. Everyone starts to shuffle into the cafeteria around me. They remind me of schooling fish, the way they are trying to avoid coming close to me. Wendy and Sonya stick back to yell out one last thing:

“Don’t try to sit with us at lunch. Don’t come near us ever again. You’re gross and weird.”

Sonya’s eyes remain on me, her smirk still there until she turns to face Whitney and together they burst out laughing as they run off into the cafeteria with the rest of our grade. I’m left alone in the hallway not sure what to do next. A teacher spots me from the cafeteria and calls me over to join everyone else.

Weeks after, at a family party, it’ll be Yasmine who will explain to me what a Lesbian is. She’ll tell me briefly in front of my cousins as a way to try and get back at us because we’ve come together to stop her from bullying us. “Get away from me” she’ll shout.

“You’re the worst of the worst. That’s why in school you are known as The Lesbian. You like other girls. A marimacha. A lesbiana. That’s why you don’t have any friends. No one wants to be around you. They think you’ll try to hold their hand or worse, kiss them!”

My cousins will launch at her after she says this and that’s the last we’ll see Yasmin. Her parents won’t want to come around our family anymore because according to them we’re violent and we’ve got a lesbian in the family.

I spent the rest of the fifth grade playing alone and watching everyone else play together. No more Wendy’s, Sonya’s or even Yasmin’s.

*****

I have thought a lot about why this memory returns to me now. An idea haunts me: Did I do something that night that exposed me? I find myself thinking. With this memory returned I can suddenly feel the sleeping volcano of shame I didn’t know I’ve been carrying with me. How did Wendy and Sonya guess something about me that would take me years to come to terms? Was it the color of my sleeping bag? Lavender is a pretty gay color if you ask me. The way I dressed? Maybe it was the fact that I liked to wear my younger brother’s sweatsuits. I pick apart all the superficial things that could have outed me so young as a coping mechanism to avoid waking the volcano of shame. But I feel it start to boil. It was probably something I said or did.

I begin to excavate. To police my ten-year-old self remembering this friendship. In the same way, I recall policing myself around women after I finally came out in college. The shame volcano starts to get hotter when I think about how I’ve policed my body and actions around other women. The volcano is playing a game with me, the hotter it gets the closer I get to understanding the shame.

I work my way again and again through the pieces of what I can remember of this sleepover:

Did my eyes linger somewhere for too long? When Sonya held my hand that night, did my touch transmit some kind of desire?

The truth is, I think I knew I liked Sonya differently then. I knew there was something about her that set her apart from the other girls for me even if I couldn’t really identify what my feelings for her were. Sonya with her big beautiful smile. Sonya with her soft hands. Sonya, who I always wanted to be around because she made me feel warm inside.

I knew I liked to make her laugh and bring her things that made her smile. I didn’t know then that the warmth I felt was more than a girl happy to have a friend. A girl doing anything and everything to make another girl smile felt in a way normal to me then. When I was ten, desiring closeness and connection with Sonya only felt like an extension of a special friendship I dreamed of having with another girl. Thinking through all this makes the dormant volcano of shame bubble even more. I’m getting closer to the truth.

I can see the blurred line drawn between the little girl I was, who wasn’t fully aware of her feelings for another girl, who seemed to only want a best friend and the adult I am now who understands some of those feelings weren’t linked to friendship at all. The full truth is: Sonya was my very first girl crush. The full truth is: Sonya was also my first heartbreak and rejection too. I had swallowed that to protect my ten-year-old self from the belief that this shame is holding on to. The belief that if I admitted to having a crush on Sonya, they were right about me. There was something weird about me.

The way I desired Sonya’s kindness and warmth was wrong because it was also linked to a desire for something that made me unlikeable. Something that made others want to avoid me, to pretend I didn’t even exist. Remembering all this is making me hyperventilate and spiral.

Could I be trusted around other women? Is that why female friendships felt so difficult for me? I’m flooded with memories of all the moments this shame and questioning has been affirmed over the years. I’m reminded of what it was like to be a lesbian on an all women’s college campus. Straight women I’d meet or befriend urging me that I found them attractive and I needed to confess to crushes I didn’t feel or pushing themselves on to me to see if I’d take the bait.

They wanted their attractiveness affirmed at the cost of my identity with no interest in pursuing anything real. Those moments affirmed the fear and shame I developed after that early unconscious attraction I felt towards Sonya and the weight of the rejection, not just from her but from everything else that came with it.

This shame is multi-faced and deeply layered like my skin. The connection comes down to the word Lesbian. The connection comes down to the links I created early on between desire and attraction and shame. It’s why when I experienced my first orgasm with a woman, I wasn’t rocked by a wave of euphoria but instead hit with a sense of doom. Desire collides with shame, turning them into one another, creating a heavy knot that sits in my stomach and silently reminds me something isn’t right about me. I can’t be trusted around other women. Emotions becoming mantras on repeat: I desire and I’m weird. I want to and I’m disgusting. I need to and I’m manipulative. I like and I’m a predator.

*****

My wife kissing me on my lips breaks me out of the pool of shame. This shame I couldn’t see before. None of that is the full truth. It’s different versions of the truth I needed to hold on to, to make it where I am today. I was a ten-year-old girl seeking a meaningful connection. A lonely girl looking for a best friend and I was also a girl with a crush on another girl. One who didn’t understand that it’s okay to want closeness, admiration and care for other girls and not know exactly when it means something more It’s okay not to police your body around other women, to trust yourself. It makes sense to me now why my body now doesn’t settle into platonic physical affection from other women. Why doesn’t it feel safe and wants to flee it. Part of me is still that wounded little girl who lost a friend because she liked her too much who hated being a girl who liked other girls.

Shame can be dormant this way. Shame is multilayered. I needed this volcano to explode. I need this memory to return. Memory gave me the chance to recognize the shame and uncoil it from desire. To uncoil it from this word that I’ve learned to embrace and call myself. Lesbian, I say out loud when I look in the mirror. Even though I’ve learned que me gusta mas dicerlo en español, lesbiana. I’ve built a home and family with my wife of almost a decade. A wife who is also my best friend. I’ve found that the two are possible. That lover and friend can exist together. And that I carry with that too, a wounded little girl’s shame that still lives on in me somewhere.

But everyday that passes, I feed her wound the closeness I’ve found with my wife. I feed her wound, memories of my wife and I holding our son’s hand as we walk down the street together – Mamá, Mami y él. And I’ll continue to feed it the freedom I’ve felt from loving, being loved and from living my truth every day. But now it will be to purposely, honor that little girl inside of me.

Lupita Aquino began her literary journey as a book reviewer on Instagram, quickly gaining recognition as a prominent voice in the book community. Driven by a mission to amplify Latine representation within literary spaces, she advocates for the inclusion of diverse voices across the broader literary landscape. Her dedication to connecting readers with diverse voices and books has paved the way for her to contribute book coverage to outlets such as TODAY.com, Aster(ix) Literary Journal, She Reads, The Washington Independent Review of Books, and more. Beyond her digital presence, Lupita is the founder of La Comunidad Reads, an author-inclusive book club in partnership with the DC Public Library. She has also moderated numerous literary events and served as a judge for the 2024 PEN/Jean Stein Book Award, the 2023 Louise Meriwether First Prize for the Feminist Press, and was a member of the Selection Committee for the 2021 Aspen Words Literary Prize. She currently serves on the Authors Committee for the Carol Shields Prize For Fiction. When not immersed in books, she enjoys exploring local bookstores and libraries with her wife and son.