Sedat Peker demanded a sacrifice. He dreamed of blood, and I dreamed the dreams of Sedat Peker.

In January of 2016, when the snow fell so thick and deep we were locked into the apartment for a week, only leaving to fetch water, bread, and rolling papers, he makes an announcement directed at the Academics for Peace, who have signed a petition in response to the acute and specific violence of that year. Sedat Peker takes it upon himself to voice the concerns of the nation, regarding these restless and rebellious university professors. At the same time, he enters my dreams.

In that year, while a war in all but name is fought in the southeast, and while the cities endure their fair share of bombs, a year that could only be sated, as it happened, by a coup, this is what he says:

THE SO-CALLED INTELLECTUALS, THE BELLS WILL TOLL FOR YOU FIRST.

A message from Sedat Peker.

We will let your blood in streams and we will take a shower in your blood. If you ask my opinion, you should not try to sink this STATE for your own health. The only reason that you are alive at the moment is the presence of the STATE and its survival. As I said in the aforementioned remarks, if the terrorists, you who are their supporters and foreign countries’ intelligence services – in sum, all of you – accomplish your goals and turn this STATE into a nonfunctioning situation, you should well know that you will never be shown mercy by THE CHILDREN of this HOMELAND.

I call the first dream the Delivery Boy Dream

A delivery boy pulled up on a scooter outside an apartment block in an indistinct suburb of the city—a bakkal on the corner, a köfteci across the street. Sedat Peker leaned over the balcony railing and rolled a Chesterfield between his fingers. I stood behind him. He had recently shaved the back of his neck. The boy below squinted up without getting off the scooter.

“We brought the blood, beyefendi.”

Sedat Peker saw the boy’s face as if it were right up in front of him. I, too, gazing over the man’s shoulder, saw the face of the boy. A sesame seed rested on the side of the boy’s mouth.

“What blood?” said the man.

The delivery boy had no time for this kind of thing. A delivery is a delivery.

“Sedat Bey, it is not my blood, all I know is that the box is marked blood and they told me to bring it to you.”

“Who told you?”

“The men in the office in Mecidiyeköy.”

Sedat Bey lit the cigarette.

“Give it to the doorman.”

The boy unlocked the crate on the back of the scooter and lifted out a white refrigerated box. He passed this to a man standing just inside the shadow of the building. Then he made a gesture up at the balcony with his right hand, and drove off.

Sedat Peker allowed the cigarette to burn halfway before he took his first drag. From where we stood the city expanded and seemed to rush down to the sea. I saw it as he saw it. As is the way of dreams sometimes, the mind of the dream was his, was him. Not mine, not me. We shared the view, and the cigarette smoke, and the dream. The sea itself lay flat and indifferent, perhaps bored of the city. He too was bored, as he smoked.

The end of the cigarette came. He stubbed it out into a potted plant and thought about the blood. He had stood on a podium; people surrounded him, waving red flags and calling for that very blood, or maybe any blood, he was never sure they even knew. Of the few things that mattered, this was not one of them. The blood in him rose up to meet the people and he cried out, giving them the words that softened their taut throats and caused them to push their hands up even higher into the air.

They shouted, he shouted. He said, “Their blood will run freely on our streets.”

“He who speaks of peace during wartime is as much a traitor as he who speaks of war during peacetime,” the former interior minister had once said.

The colours of the day began to press on him. The city’s walls, all of its walls, grew heavy and threatened to push down into the earth, pulling with them all the carpets, hanging pictures, cabinets, fridges, couches, lovers, samovars, house slippers, disquieted housewives, dogs, televisions, sausages, and bags of sugar held within the walls. All of it would sink into the earth and the sea and there he would stand, the only one to have recognised that this was what was coming and to have relished it.

This was why he was bored.

The presence of the blood downstairs annoyed him. The smell of blood made him feel ill and he avoided it. Besides, to shower in blood would cause a great mess, and the scent would linger. He could, he reasoned, stay with his mistress until the smell faded. That thought pleased him. But how would he get the blood to come out in a shower? Should he bathe in it? It is important to follow through with one’s promises. He had said shower. “I will take a shower in your blood.” Ah, fuck. He went inside and down the stairs, passing a sleeping woman and me on the way there.

In the shadow of the doorway the doorman stood. Light from outside fell at his feet.

“Sedat Bey, selam aleyküm.”

“Aleikum Aleyküm selam.”

“Here it is. Where shall I put it?”

The man paused. He pulled another Chesterfield and this time he turned to look at me. The dream got louder.

“How do I know that this is the correct blood?” He looked me in the eye.

The doorman answered.

“How can I know?”

Sedat Peker turned away from me. He said only, “Ah.”

Blood is blood. The origin of the blood is by now besides the point. It could be ox blood, or horse blood. He looked at the box in the doorman’s hands. It had a delivery note taped to it. At the top was a crest. The Ministry of Justice. So, real blood then.

Satisfied he said, “Yes.” And then, “Put it in the fridge.”

The dream ends.

In the waking evening, after a hot day, we listen to Marvin Pontiac with the windows open. I’m a doggy, and I’m naked almost all the time. The turunç tree beyond the window is heavy with fruit. The fruit in turn are heavy with snow. My soft-eyed friend paces with strides that are not soft at all. He’s reading. I’m rolling a joint over the pages of my open book.

I say, “Can I read this to you?”

He says, “Sure. Go ahead.”

It’s from Ka, by Roberto Calasso.

I read.

When Śiva wiped out the world, all combinations of existence would flow within him, without needing to exist. The mind and the outside were not separate entities – perhaps not even entities at all. Penetrating each other, they lost all their shyness. The stream was one. The dreadful and the delicate surfaced together, in pairs, indifferent to each other, like distant relatives. Then they bid each other goodbye. Immediately something else took their place. An incessant migration. All forms, all forces: they were Śiva’s herd. That’s why they call him Paśupati, Lord of the Herds. ¹

¹ Calasso, Robert. Ka, (Vintage, 1999), p. 121

My friend rises and walks to the window, opens it and leans out to look at the turunç tree. I put the book down and shut my eyes. Soon I am asleep, but I can hear him speak even as I disappear.

So began the second dream of Sedat Peker. I call this one The Seer.

I am in the kitchen. He comes in. He says, “Make me eggs with sucuk.” I reach for a frying pan. This time, we are separate. He has come to visit me. He sits on a chair where he can see me work and begins to speak.

“Knowingly or not, I have a role to play in your life. And role is an apt word for it: you believe that you are the central actor in your life, and yet if there was an audience who watched your caprices and your turmoil from comfortable seats at a safe distance from all the spitting and crying, they’d be able to talk amongst themselves after the show and say. Well, she was great, you know, really convincing, but of course the thing is that she didn’t understand anything at all. I suppose it’s a metaphor for modernity, they’d say, What with that character lurking around behind her all the time conducting her affairs without her knowing it, she really has no say in much at all though she believes she does. Such is our condition, they would say, And we shall not know the culprits until we know ourselves. Let’s have a drink on the terrace, they will say.”

I crack eggs into the pan, over and over. Thirty eggs pass between my fingers, fifty, a hundred, and none sticks. They slide from the pan, onto the floor and out the window. The man goes on.

“Character is a misleading word for me. I’m not a mere character – like you I’m a person, and I’ve a name and a family. There are state files recording my movements and the names of my parents, my religion, the hospital where I was born, whether or not I’ve done my military service. (I have.) I am cemented in reality. I even pay taxes. The difference is that I know what is going to happen and I’ve decided to prepare for it, whereas you think you have some idea – or you don’t care – but it’s neither here nor there what that idea is. I’ve never stopped working; you sit and take photographs of yourself, to share or to delete, obsessed as you are with a fairly limited range of concerns. It’s not even that I’m watching you all the time – I don’t need to, you do it for me. Everything you do is so well recorded that for a while I became suspicious that you’d caught on to what is happening to you, but then I realised it could not be so. How charming you are, how free of true deceit. Of course to those around you, you’re a liar and a flirt, a cheat at cards, a desirable conceit, not a real person but an artful representation of one.

“Wait – perhaps I have underestimated you. You have causes, and lovers. What you lack is the long vision of things, and the will not just to plan for them but to form them. I saw it coming, all of this, and shaped myself as I needed to in order to be prepared. You really do like to look at yourself in the mirror. You also look at photographs of people that you love or have loved. I understand that you read certain serious books. I see also that you have recently developed a taste for blood sports. You also read and watch the news, in order to keep abreast of developments. Is that enough? Sometimes you even read about me. Did you see my videos?

“You did, didn’t you. You enjoyed them. There was that one with clips of me making speeches about the Chief – I mean, when in history has an uneducated boy from the sticks, from the back quarters of the city, from the hard but living streets, become the powerful and beloved leader of a nation that bends to his iron hammer as hot metal bends to the hands of a smith? Never? No, many times. Oh, but it’s an old story. We knew our turn would come. The question remains as to what happens next. But I do not speak of this. I think about it, and I make notes.

“Of course most things seem to us – here I put you and I, as humans, in the same category – to be special. In fact they are not, or not in any fundamental way. You were recounting that to friends just the other day. Yes, it was me you saw there. Someone had told you, Repetition is very important, and you remembered that.”

I slice the sucuk. While I slice it, I begin to speak. Pieces of sucuk collect at my feet like my own hair. My hair begins to fall too. A dog with a head hewn from stone eats the sausage, one piece at a time.

“In the 1950s there was the boy from Aydınlı. His name was Menderes.”

“Yes, go on.”

“He came along with the vote of the peasants, ready to build roads and offer the people freedoms they had been denied.”

“He did, indeed.”

“The former he succeeded in.”

“Thank you, America. Thank you, Marshall Plan.”

“But by 1961 Menderes had been executed and his government overthrown.”

“You’re interested in that, aren’t you.”

“I am interested in patterns. Repetition is important.”

“Repetition lies.”

“Now the pattern is like this. A party comes in on the promise of reform but sets to work in secret separating the population into two categories, the People, and the Elite. Tensions rise. The party makes sure everybody has an enemy.”

“And then what?”

“And then there is a coup. Like clockwork, every ten years. Give or take. And it all begins again.”

“Which is why you said to your friends, It’s just one fucking thing after another.”

“It’s not my line.”

“One fucking thing after another.”

Now the dog rests its head on his leg. Sedat Peker points at my chest as he speaks.

“You do this, you read, you write, you follow things, every day there is something new, but nothing changes. And you can’t see how it all works anyway. It’s sweet because you’re a bit drunk from rakı and swimming in the sun for so long. Your friends nod and laugh, they agree, they’re also just about at the point of ducking out of all this, the world we were raised to believe was ours. (I was right, you were wrong). The girl opposite you talks about getting some goats on a farm, and you offer to look after them while she works in the big hospital in the city. You do this because you are in love with her. There is more drink, and you make fun of a woman who is standing in the water wearing a head-to- toe pink swimsuit made of the same stuff as men’s swim shorts. The tall girl says, If you don’t want to see naked people, then just don’t come here.

“You like to be on that girl’s side and so you agree. But you probably feel bad for making fun of her. You think, How petty is God? Would he punish you, for mocking a woman who covers herself even while she swims? If that woman’s God is real, and he rules you too, what will he take from you? What is it you are ashamed of? Is shame your God? Your tall friend has no such concerns; she makes no bargains with spectres. Drunk and stupid in the sun, and thinking about God, you catch sight of me, don’t you, in the pines behind the little hut where a woman is making fried zucchini flowers to serve to you with yoghurt.

“I do follow you.”

He keeps speaking. I slice and I listen. The dog watches me and does not blink.

I wake. I am on the couch, and a man is standing in the room in the dark speaking to me. He is a man I know. I am awake. This man, the waking man, paces as he talks. My hands are folded over a pack of cigarettes. My clothes are on the floor.

“Well I mean life is just one fucking thing after another, isn’t it? You read about Śiva, and all the other gods. It seems to me also that you’d be able to grasp the fundamental thing about those gods – they’re not gods the way the people chanting Allahu akbar or fantasizing about the Pope would expect. Those gods are all-powerful and omnipresent, waiting in the shadows of everything and with one eye on the clock at all times. Doomsday is always approaching, the whip and the balm always in the same hands. These gods – the ones you and I grew up with, gods who originated in the sacred red parts of the world – see no limit to their powers, and we are expected to behave accordingly. We are expected to be contrite. They are not ‘they’ at all but He, just the one, and it is not enough – or maybe it is, I don’t know, I feel fucked when I think about it.”

Sedat Peker sits on the couch now. The sausages and the eggs and the dog are gone. He answers my friend.

“You are right to be fed up with that type of god, given what has taken place here. No doubt this is why you are drawn to the gods this girl is reading about, Indra and Śiva and so on. I myself find them useful models, too. As one of the brahman explains, these gods may be gods alright but they’re as vain and petty as men – though they use men to achieve their own ends. Man thus has some of the nobility of the workhorse. Man is tamed and useful, a little dumb. The gods are capricious, they leap around the world forming its mountains and its myths with their escapades. They make love and pursue underage women; they seduce and destroy kings, and kill themselves for love and desire. To them the world is a casino.

“The world of domesticated animals is the world of men; the world of wild animals is the world of the gods. But as you will see from this comparison they are nonetheless driven by instinct, which some would call base by definition. They seek out things that you or your friends seek out too: love and sex, the bodies of others, sweet food and cool water in the summer, a home, blood. They are grand because they are the gods, they emanate from the origins of Time and Matter, and so their stories become myths and archetypes by which men are desperate to live. Yet they discover little that they were not born with.”

My friend stops pacing to squat in front of me. He touches my face. “Then what do we know?”

“What?”

“Wake up. You always fall asleep. What did you say?”

“I saw Sedat Peker in my dream, and he was telling us something.” “Ya? What was it?”

I roll over, sit up and light a cigarette.

“You want to know? He said something like this. ‘It is the Seer, the one who does nothing but observe the force of life that dwells within him and all things, who comes closest to power.’”

He takes my feet in his hands. I put my hands around his face. I speak the last words of Sedat Peker.

“Yet here again power is not what you or I was raised to believe it to be. It’s not the ability to strike down the enemy or force your will on the nation. Power here is knowledge of the fundamental truth of the universe. It is harmony of the opposites that both observe and constitute each other: the mind, and the self that watches it. The Seers were the ones who approached this kind of force. It is them I wish to emulate. I carry the gods in my pocket to remind myself that they are not the limits of possibility.”

“I hope he dies.”

“He will.”

The third dream is called Chickpeas.

I am on an island. It’s a tropical island, and F-16s fly past overhead. My father is sometimes with me on this island, helping us, the guerrillas, with engineering works. He is there this time, pointing to a gash in the land where the earth needs to be cleared. Next to him is a man in a white shirt like a waiter carrying a big metal dish, more like a tray. His mouth is a gash like the one in the earth. He would bow low if I told him to. There is something weak in his face. Is he a supplicant now? With confused eyes he calls at me, offering me the food that he carries on his tray. He wants to help the war effort. The tray is full of chickpeas cooked in tomato sauce. He has a table now, and some plastic bowls. Here, here, eat, he says. He is Sedat Peker. He hands me a dish of chickpeas in tomato sauce, and walks on with his tray.

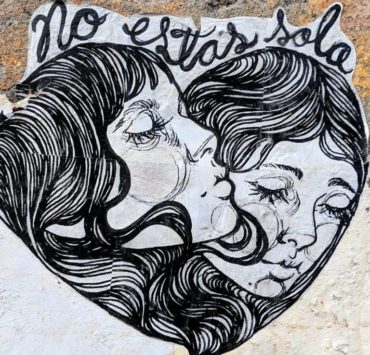

Image Credits: Frédéric Glorieux

Olivia Rose Walton is a writer from South Africa who lives in Istanbul.