Posted 2/4

The Coffee Klatsch

For a short time, I was in a coffee klatsch, a group of Brooklyn mothers, all of P.S. 29 second grade girls who palled around with their braids and their girl scout uniforms and, on Fridays, went to gymnastics in Manhattan. Manhattan! These girls and their mothers and I and my girl would take the A-train to Chambers Street, the girls playing souped-up versions of pattycake, the mothers complaining about the girls or the husbands or the jobs they had left for the husbands and the girls. Quite religiously we’d meet at the little coffee shop on the corner of Warren & Court, and Sarah, the very rich one might already be a little high, and Mandy, the really broke one with the videographer ex would probably be crying a little, and Jami would have her paper calendar and be very on top of things, and Leah would be a little under the weather, and every time we’d meet, I’d empty two packets of Sweet & Low into my matcha green tea, and I’d have this nearly imperceptible fantasy while stirring the Sweet & Low into the matcha that I would cause an explosion, that our little corner of Brooklyn would suddenly burst into flames, that I’d have to watch, first, the invisible make-up melt off, then the skin of the faces, the skin around neck, the clavicle, the bones of the arms, and one day, I said, Sometimes, I worry my Sweet & Low Matcha will cause an explosion. Someone laughed, said, no, but it will give you cancer, which is why I bring it up now. One of the lesser discussed aspects of having cancer is imagining all the poor choices you made which contributed to it: there are the cigarettes, of course, cliché!, all that wine, also cliché!, but then there is the Tab my mother fed me from a straw, the vats of French onion dip that held me over during the first one hundred days of isolation, the huge bites of orange mac & cheese I still take from my daughters plates, the fish sticks, the lettuce unwashed, pears absently devoured without even cleaning the skin on my blue jeans, even the air, just walking around breathing the air, sucking it in, and the stress, how people say, you’ve always been quite hard on yourself, the very Virgo-ness, the every little packet you have ever ripped open anticipating the end of the world and finding, well, finding what you find.

The Long Ride Home

Mother and I take a black car from uptown to Brooklyn. There are sirens and rain. At home, I will sketch pictures of birds onto a large silk sheet, though I do not know how to sketch and have forgotten the curvature of birds. This one has large wings. My friend sent pink cloth to make the body. On the bumps, I hold my breath, and the driver, looking in his rearview mirror asks if I’m okay, says I’ll be okay. There is an okayness in the world, yes, even though the color of fresh blood is startling. I say, even the weather is okay today, and the driver agrees. He is an ornithologist, he tells me. Mother stares out the window: a flock of dreams grazing in the cemetery. That must be interesting, I say. It is interesting, he says, if you like birds. I do not want to laugh because it hurts to laugh where the doctors cut, and also I don’t know if the driver means to be funny, so I just say, yes, yes, if you like birds, it is interesting to be an ornithologist. If you are tide-curious, it is interesting to visit the museum of the moon. If eros is obsolete, it is interesting to cover your body in flowers, to place lady slipper orchids where your flesh used to be, china berries up your nostrils, tree peonies in the soft space of your open legs. Already, I’m intoxicated, and the glass is shattered, and the ocean is oval. Here we are, the driver says. We have pulled in front of a pretty brownstone. A hallucinatory citadel. This looks like a nice place to live, he says.

Timeshare

Two days after my cancer diagnosis, I invested in a fractional real estate property on the Yucatán Peninsula. For a small annual fee, I could access the ocean. For a small annual fee, I could wake up in a salt-slicked room where others had woken up, and others would wake up, and I could pull the coverlet to the pillows, walk the winding path to the sea, stare out at the horizon, and think about desire, or despair, or finding a cup of good dark coffee, or the words mother used to use when she had something difficult to say. I’ve often been uneasy about ownership: my husband, my dog, my hydrangeas, my self; it all feels so arbitrary. But to sign my name for 1/104th of a thing felt manageable even to me — a tiny sliver of mine, all mine, like in the earliest moments of morning when, if briefly, you give yourself completely to that small piece you can truly claim.

Breathing Lessons

I have been practicing holding my breath. The radiologist says if I can hold my breath for forty seconds it will make everything easier, so here, writing this sentence, I hold my breath as long as I can; I even punctuate with a semicolon so I may hold my breath longer. It occurs to me that this might give me more months, more years, which would make many things easier, except maybe aging, or retirement money, or unrequited love, or remembering. It is harder to remember when you get older. Memory starts taking on the shape of dreams or the shape of a childhood television show. The fuzz and bunny ears. The snow. Your brother taunting you; your mother running bathwater; your father, in another house, stirring his other children’s macaroni. I think if I get really good at this I could swim more in the coming summers. The blue pool. A sort of drowning without drowning. A swan dive. Butterfly. In graduate school, I learned to write sentences that held their breath for so long you had to take a breath while reading them. This didn’t get me very far. To the corner with the dog, if I can put the leash on her; alone, if I can’t. The radiologist says everything she does is to protect my heart. And though I know this is not true, I appreciate the kindness.

“The Coffee Klatsch”, “The Long Ride Home”, “Timeshare” and “Breathing Lessons” are flash essays from the collection Everything is Temporary by Artist-in-Residence, Nicole Callihan. They were previously published in On the Seawall.

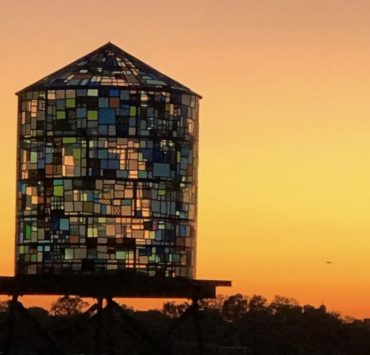

On September 29, 2020, Nicole Callihan was diagnosed with breast cancer. A double mastectomy, a lymph node dissection, radiation, and hormone therapy followed. All the while, she committed to her everyday practice of making art. Many of the recordings were originally posted to the weekly open-mic series, Wednesday Night Poetry; the images that accompany the poems were selected from her Instagram collection @thebluepitcher. These are poems and notes she took in the months that followed her diagnosis.

Image Credits: Nicole Calllihan

Nicole Callihan’s most recent book is This Strange Garment, published by Terrapin Books in March 2023. Her other books include SuperLoop and the poetry chapbooks: The Deeply Flawed Human, Downtown, and ELSEWHERE (with Zoë Ryder White), as well as a novella, The Couples. Her work has appeared in Kenyon Review, Colorado Review, Conduit, The American Poetry Review, and as a Poem-a-Day selection from the Academy of American Poets. Find out more at www.nicolecallihan. com.