So I landed in Gothenburg.

I was met by my hosts and they took me to the Konstepidemin, where my studio was. And one of the first thing they told me, as we trammed across the city, was:

‘Gothenburg society is very segregated.’

‘In what way?’ I asked.

‘In the bad way.’

I think perhaps they felt they had to warn me, based on my appearance, and, coming from the freedom of London, and having grown up in an expat community where most people were Other to a certain degree, I felt myself immediately stiffen, wondering what indeed my month here would be like.

I thought immediately of James Baldwin’s essay Stranger in the Village – in which he documents his feeling of otherness in a small Swiss village in the 60s. I’ve always had a strange relationship with the essay – the nuanced way in which he describes some of his encounters rings so true to me, but, while I respect his anger, my own experience of race had never purported to it.

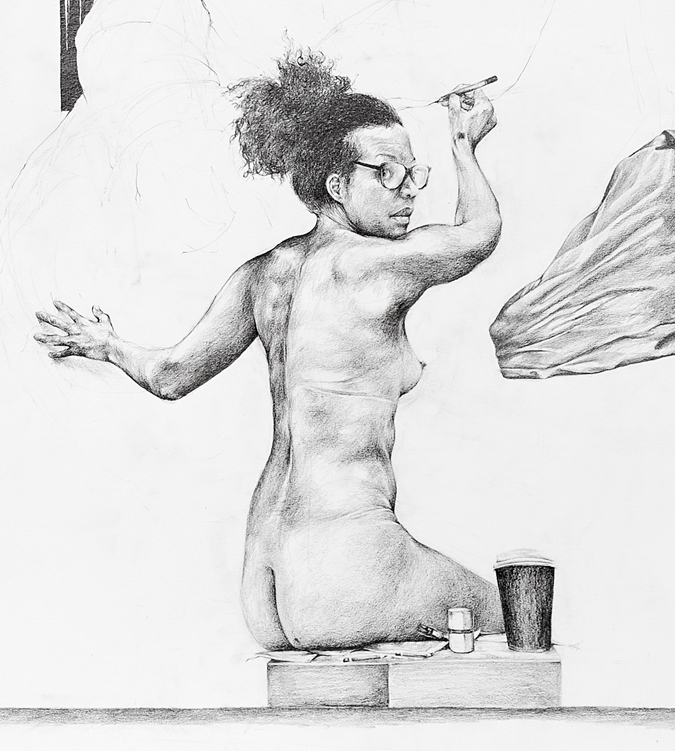

And, of course, Gothenburg is Sweden’s second largest city, so not at all the tiny village in the mountains, but still, in documenting his experiences within a new place, I thought I would somehow try and do the same, through drawing.

I kept thinking about this word, segregation. It is a big word, a bloody one, stabbed with historic wounds of injustice, soaked with cycles of historic trauma. I started to explore the city. It is pretty, and also pretty small for a city. It is connected via an intricate web of tramlines. It’s neat, and polite, and ordered. People seem to stick to the rules. Segregation. I wanted to try and get a sense firsthand of what she had meant. I needed to meet people, to interact, to see how people here interacted with me, whether I would feel some sense of this segregation. I went to a bar and ordered a glass of wine and kottbullar with lingonberry jam and tried to look approachable and uncreepy. It didn’t work. And then it hit me.

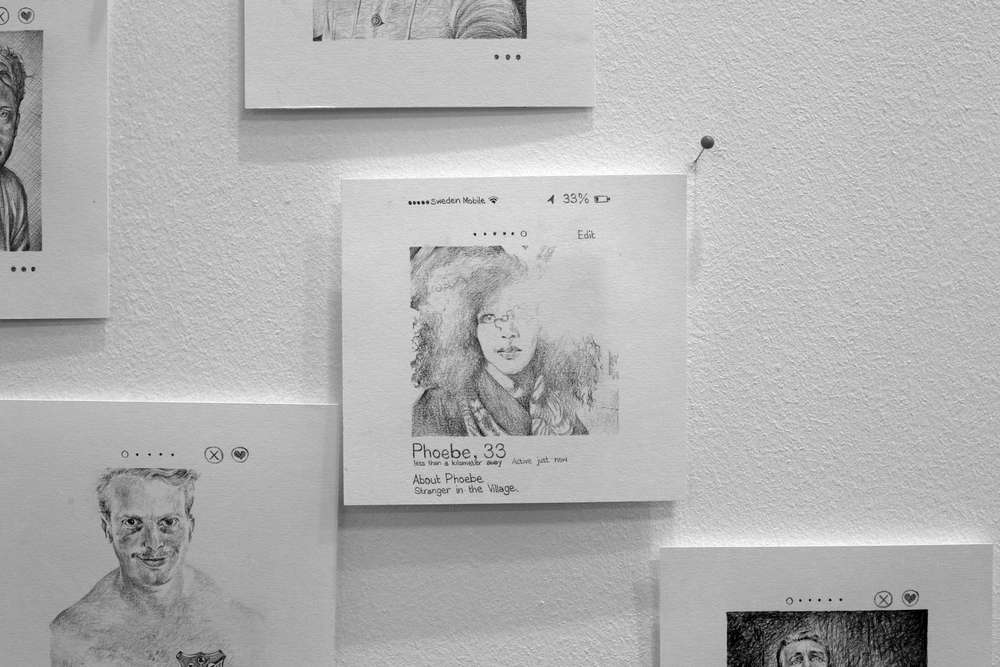

Tinder.

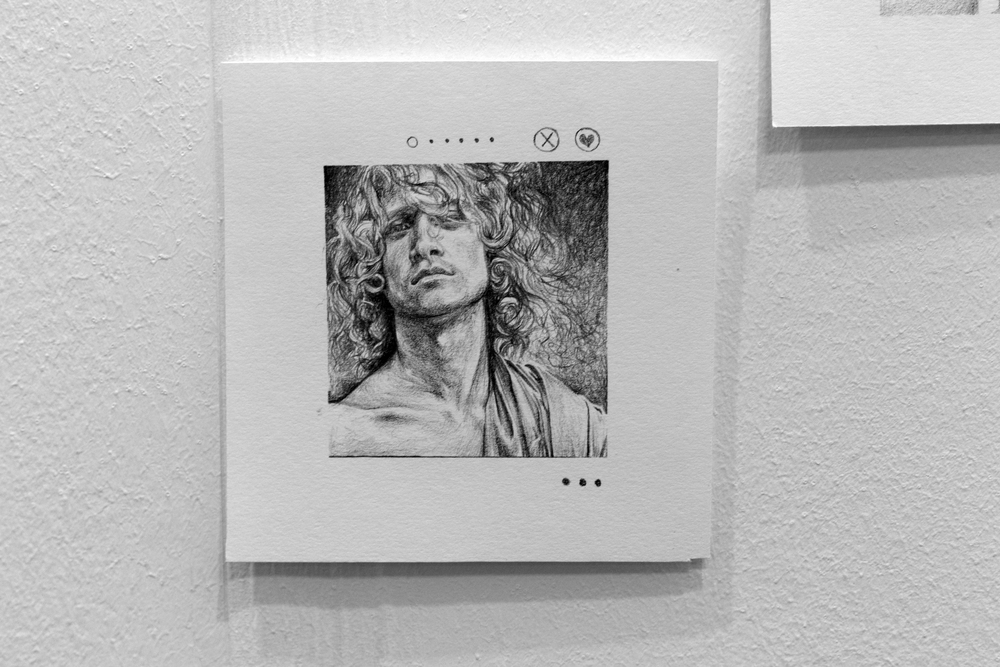

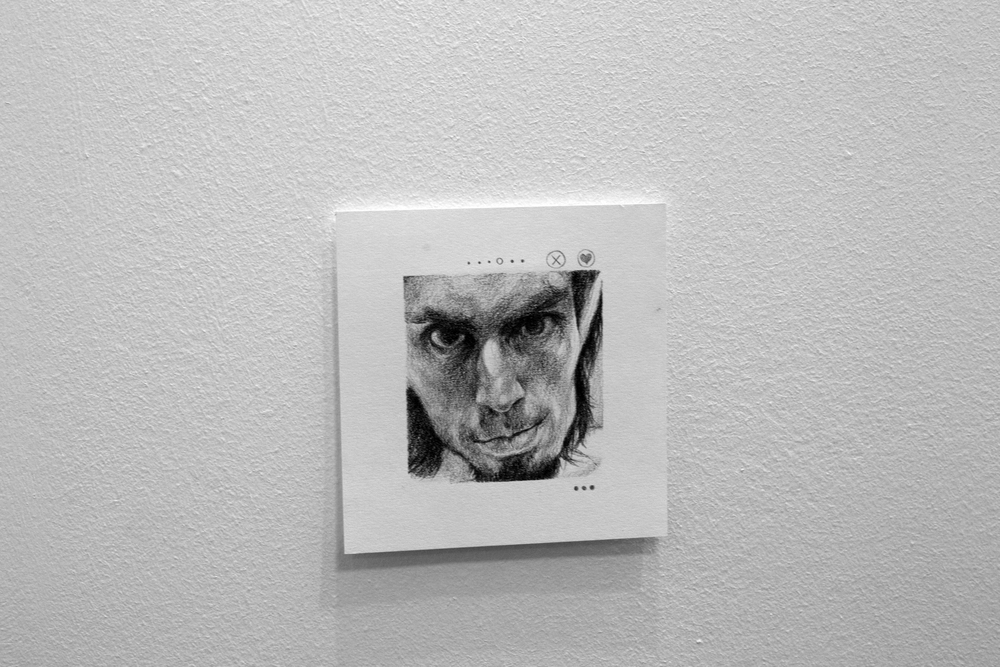

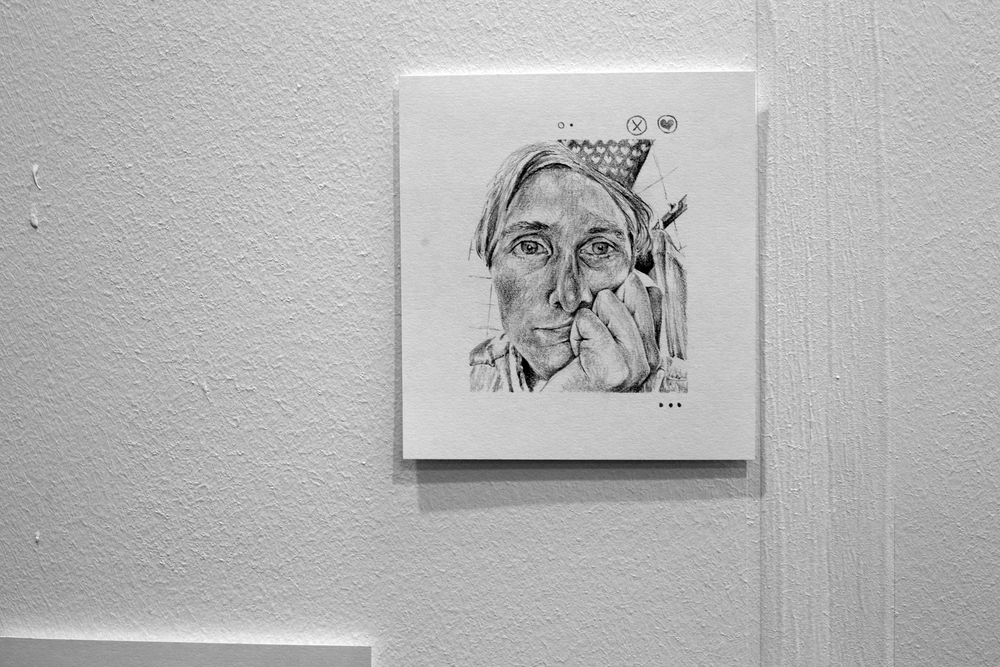

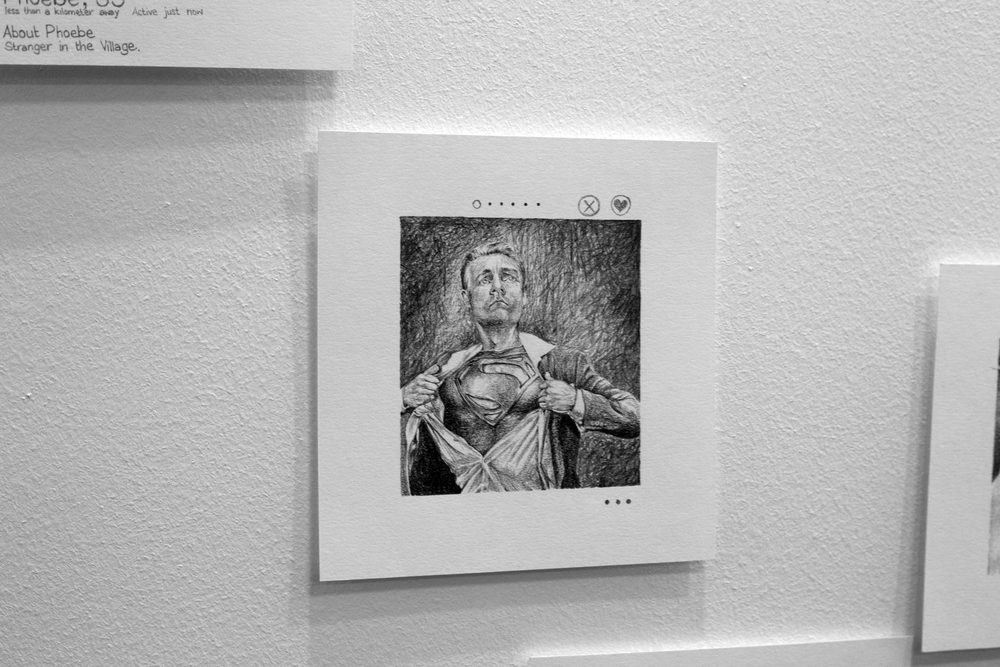

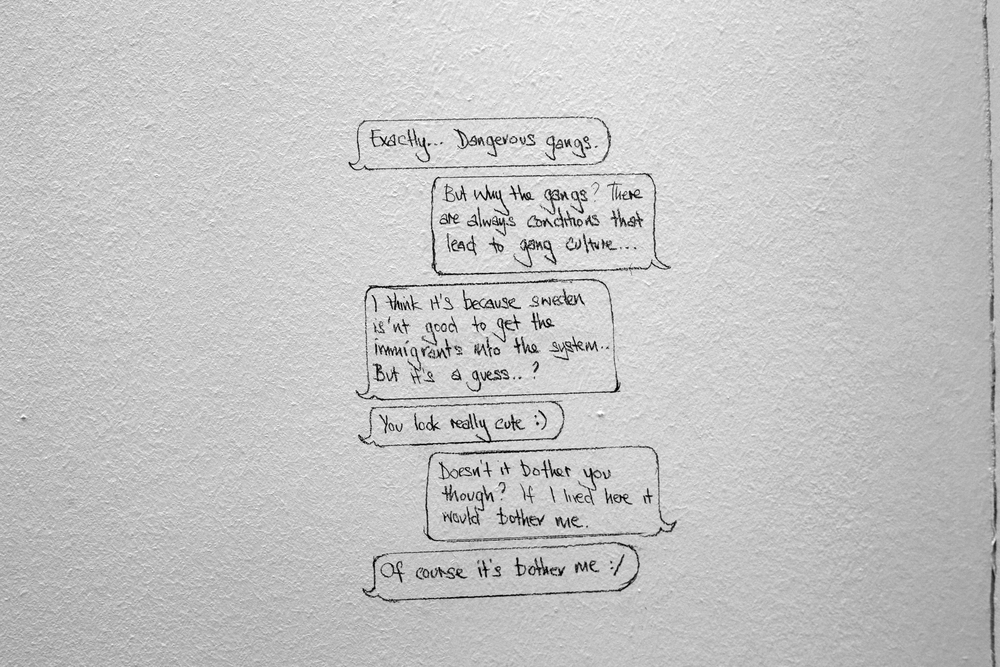

Seriously, what better way to connect with a broad spectrum of people, and to get a sense of how a city views you and relates to you than a superficial hook-up site where people in your vicinity swipe right or left purely based on your photograph! It was perfect. So I registered,

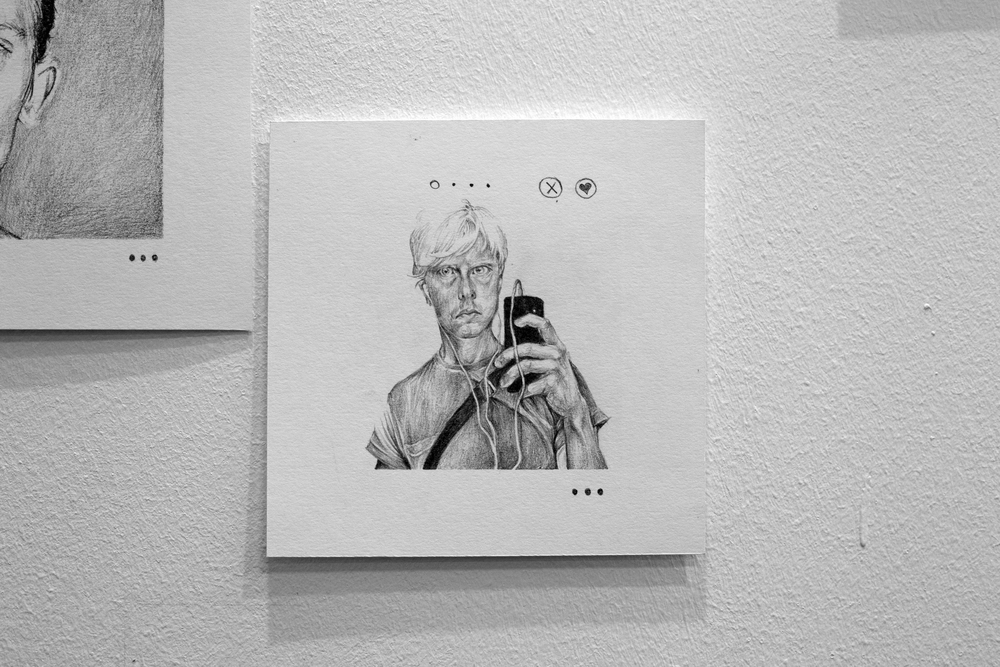

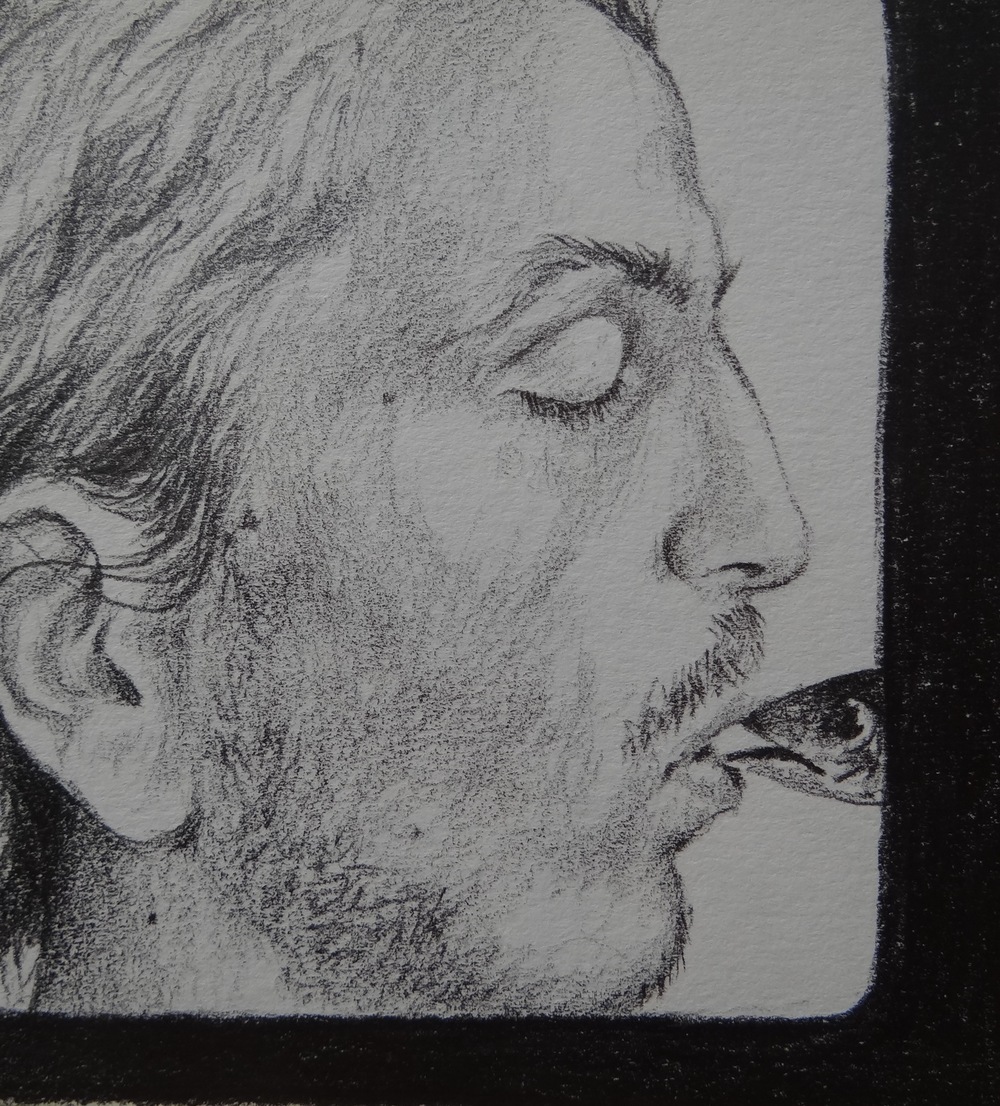

popped my picture on it, with the status Stranger in the Village after the Baldwin essay, and I began to swipe a smorgasbord of Swedish boys, testing out who, within a couple of kilometre radius from my studio in Linneplatsen, would swipe back. Each day of the residency, I would choose one to draw, whether they swiped me back or not. It amused me to spend hours drawing these intimate pictures of complete strangers, willing them to life as it were. It seemed to mimic what actually happens on Tinder, you start conversations with people you have never met, willing some kind of intimate connection. So the project began with these drawings, and slowly, as conversations started to trickle in, I started to document those too.

And let me tell you, you can learn an awful lot about segregation from a Swedish Boy Smorgasbord.

So

There were the models giving zoolander realness

The musicians giving psychopath realness

The boys-next-door taking selfies in their bathrooms wearing party hats, just straight chillin

The Supermans busting out.

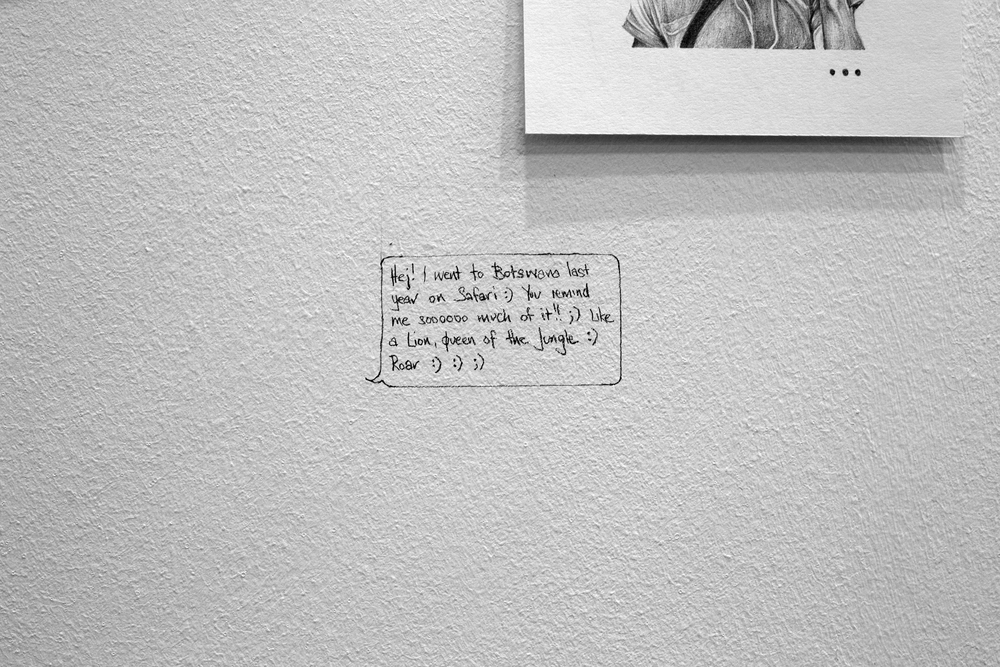

There were the intrepid traveler ones who opened with,

“Hej! I went to Botswana last year on safari.

You remind me so much of it!

Like a lion, queen of the jungle,

Roar.

Smiley face.

Smiley face.

Wink.”

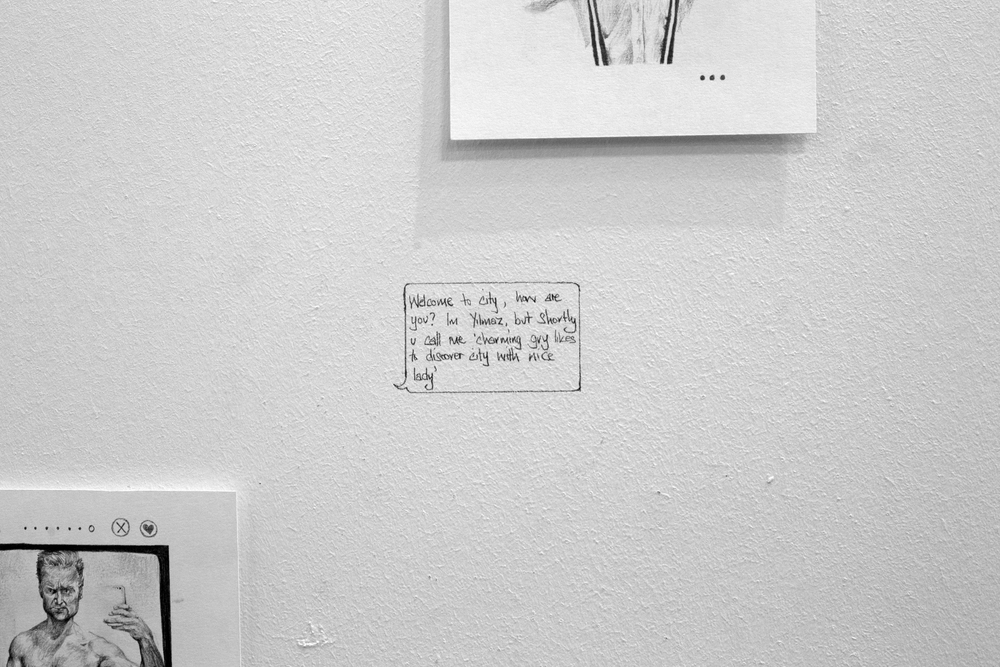

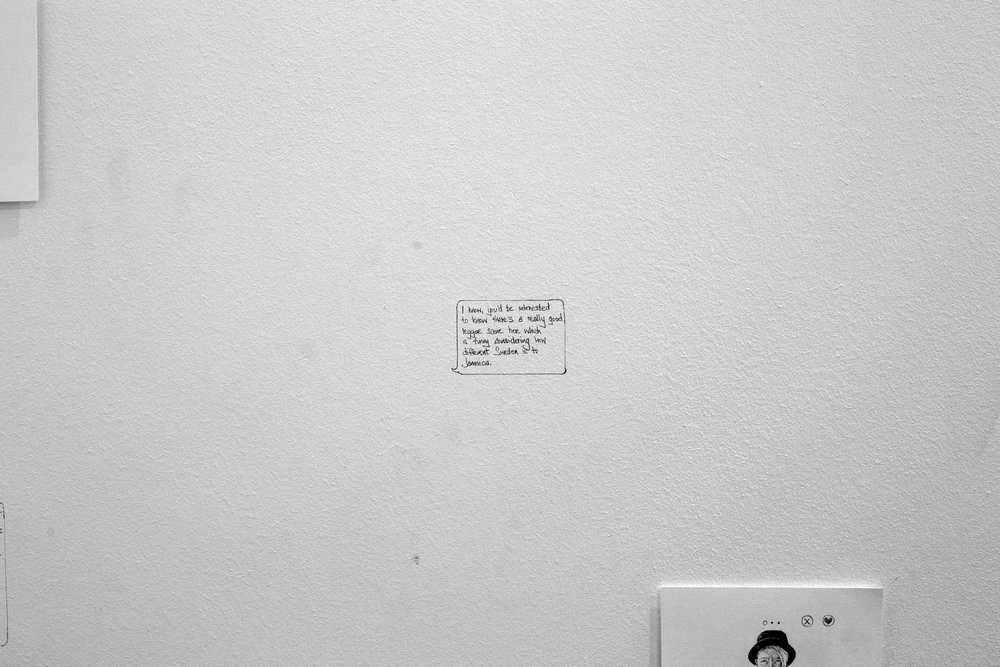

The welcoming committee ones who just wanted you to feel at home

“You’d be interested to know there’s a really good reggae scene here…”

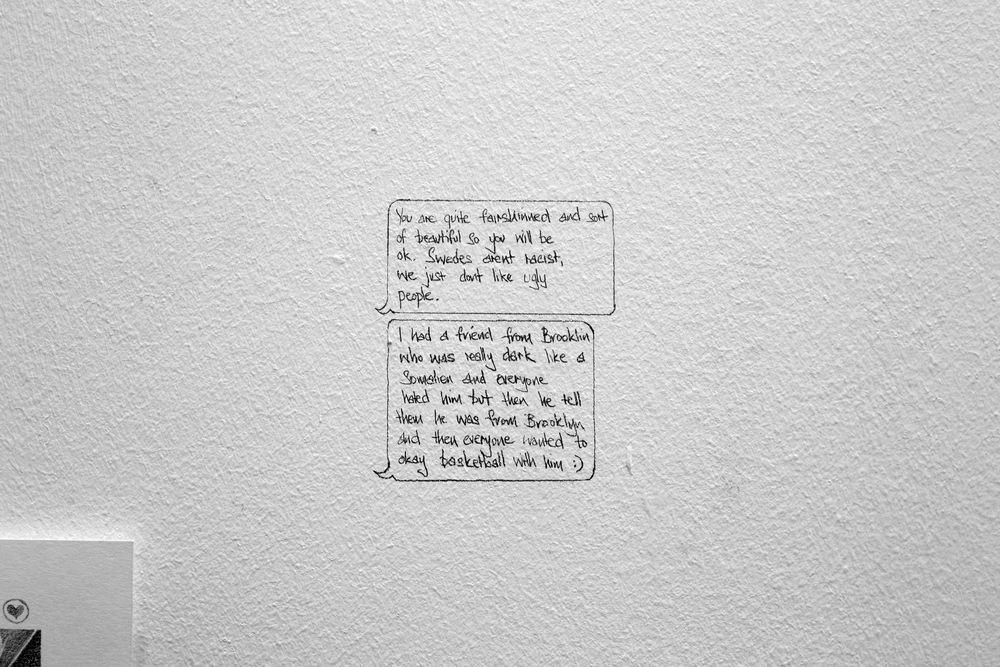

And the ones who wanted to reassure you that everything was going to be fine.

“You are fair skinned and fairly beautiful so you’ll be okay. Swedish people aren’t racist, we just don’t like ugly people.”

At the start of Baldwin’s essay, he says, “It did not occur to me – possibly because I am an American – that there could be people anywhere who had never seen a Negro”. Indeed, this fella, once I told him that my whole tinder presence was an art project and a bit of a social experiment, proceeded to offer to take me to his hometown, where the majority would have in fact never seen a black person, and he would stand some distance away so I can “experience the reaction”, and when it all became too much, he would step in and save me, because he is “very well respected in his hometown”. He ROFL’d and said it would be fun.

It’s interesting to see how people portray themselves on these things. There’s something sort of earnest about Tinder – it’s all people who just want to connect with other people – and in that regard, there’s a sense of putting one’s best foot forward. In general – and I’m generalising massively here, but I did spend a good few weeks virtually entertaining these chaps, so I’m something of an expert – the Swedish tinderman’s approach to seduction is humour.

This fella’s kissing a fish, for example. LOLz.

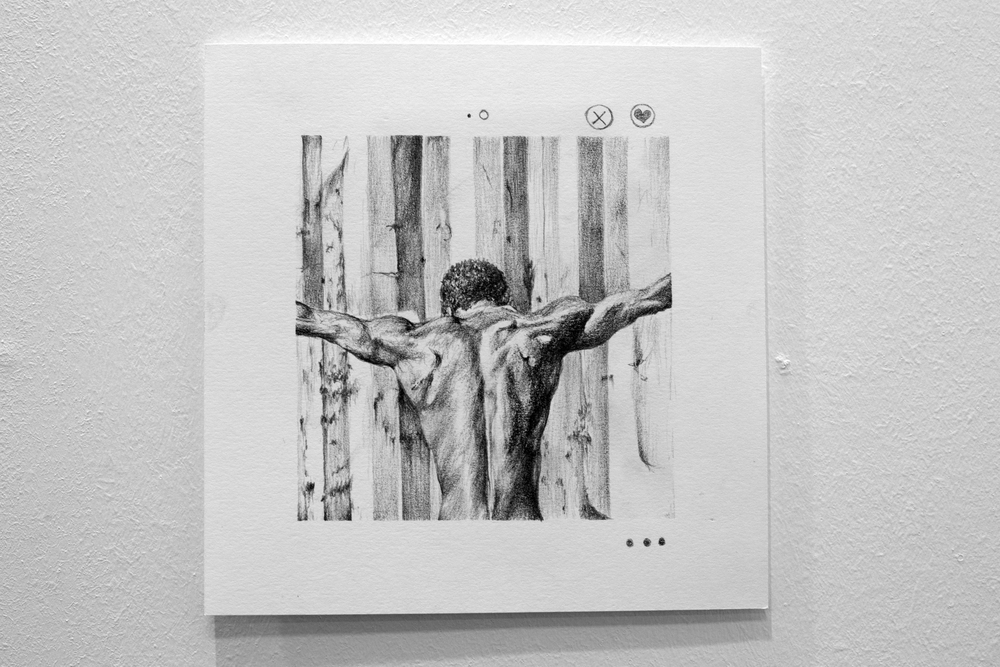

The Africans, however, of whom, around LInneplatsen there were only a handful, I noticed seemed to curate their calling cards in a far more fetishised way.

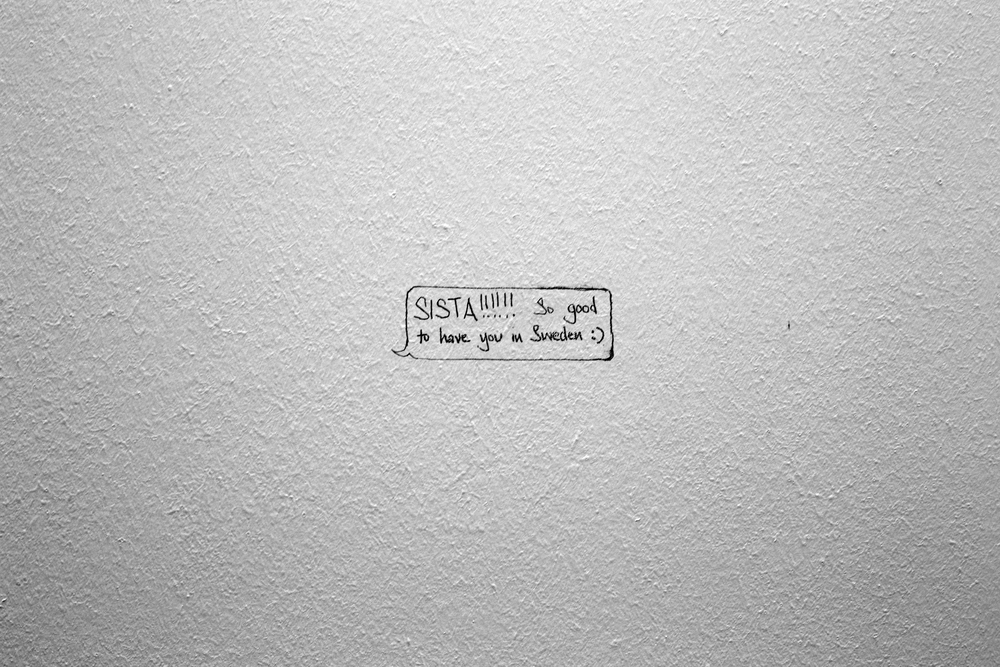

There were lots of black bodies, buff and ready, mostly without faces. Swipe right, ladies, for this exotic plaything! Baldwin would have gone nuts. Interestingly though, whenever an African man connected with me, which wasn’t often, despite the sexual nature of their posturing, it was immediately familiar, platonic, “sister!”,

as if something about my presence made them feel less homesick for a minute.

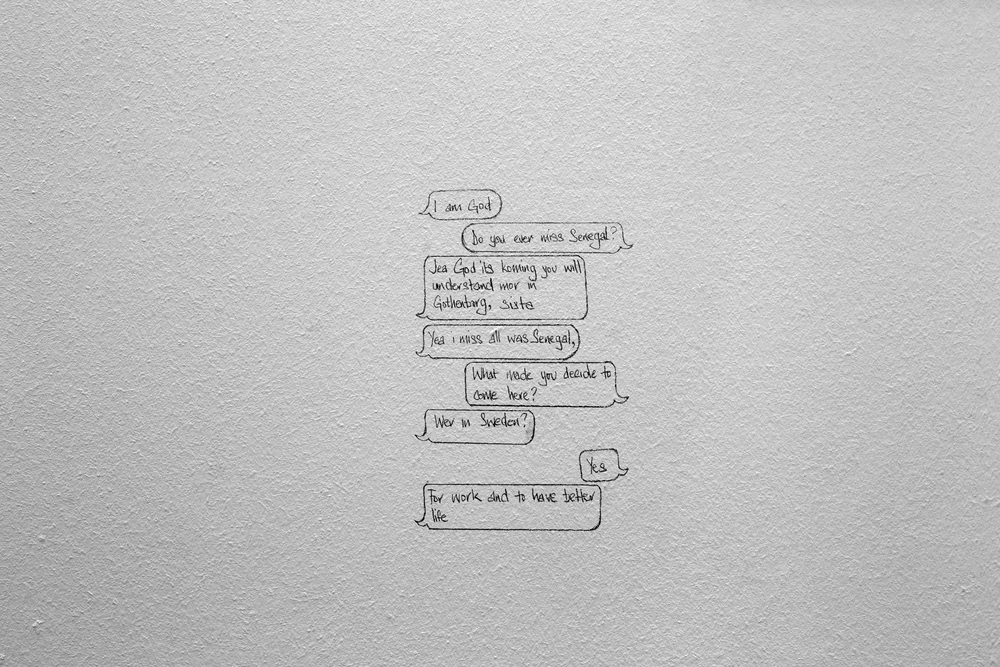

Through these conversations, I began to learn about and piece together the social intricacies of the city.

I began to mine our conversations for clues, for information on where to look, what to look at, who to look for. Everyone, bar none, agreed that the city is very segregated. Noone seemed particularly frustrated by it – it was just the way it was. The tramlines, which were the first thing that struck me about the city, I learned, not only connected the city geographically but disconnected it socially. I learned that there were certain tram routes on which you would only see white people, and others that you would only see brown ones.

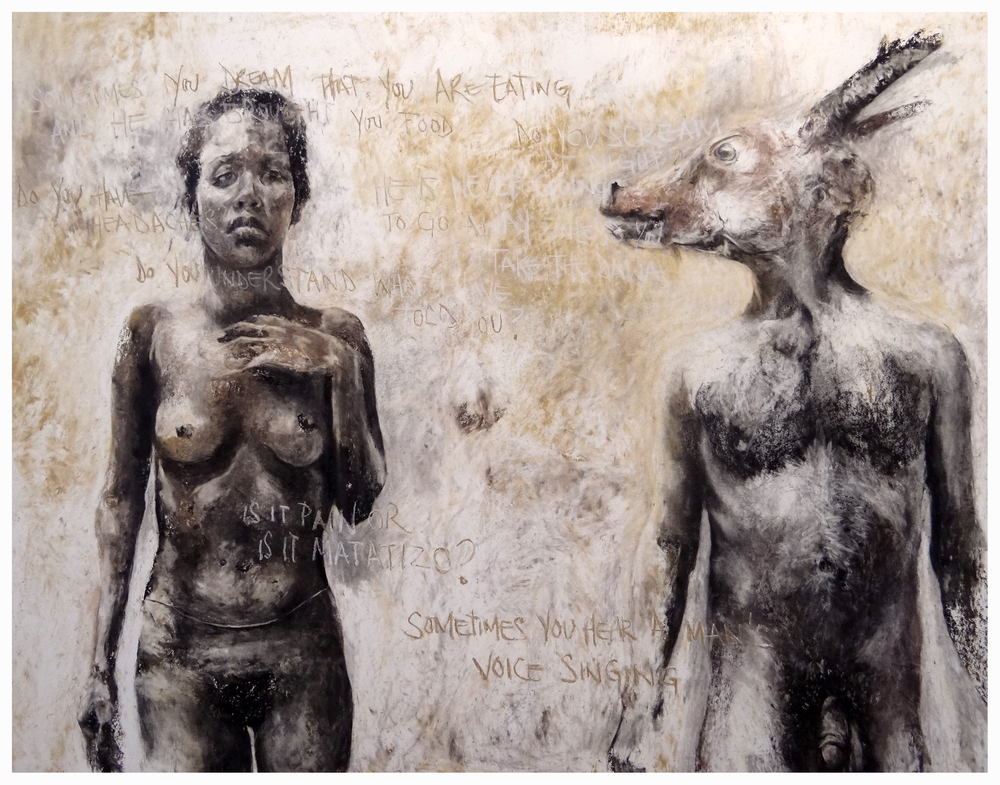

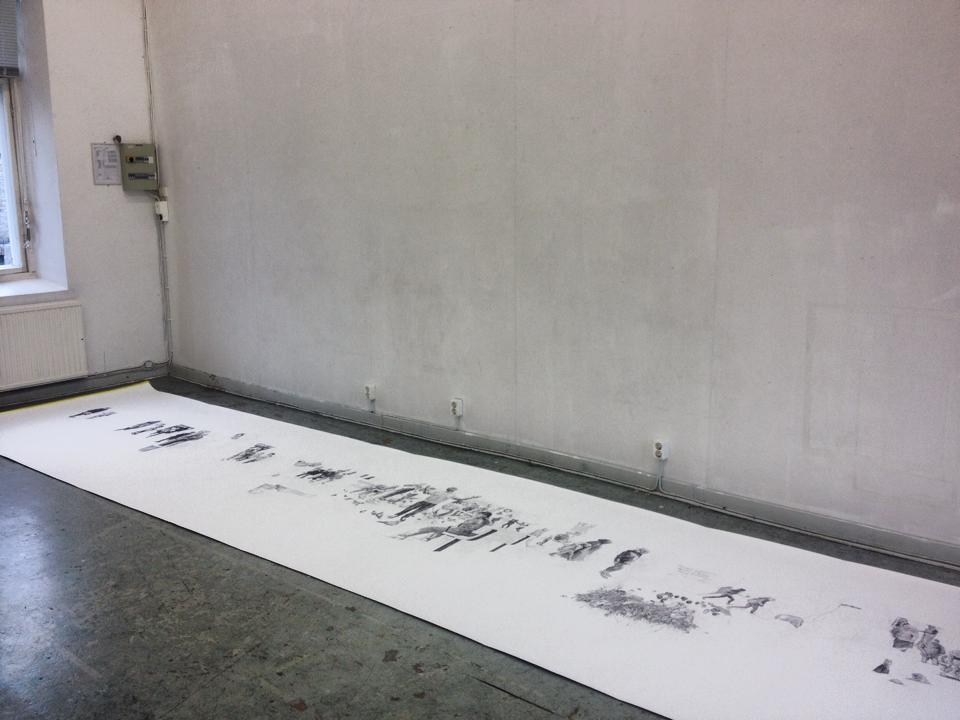

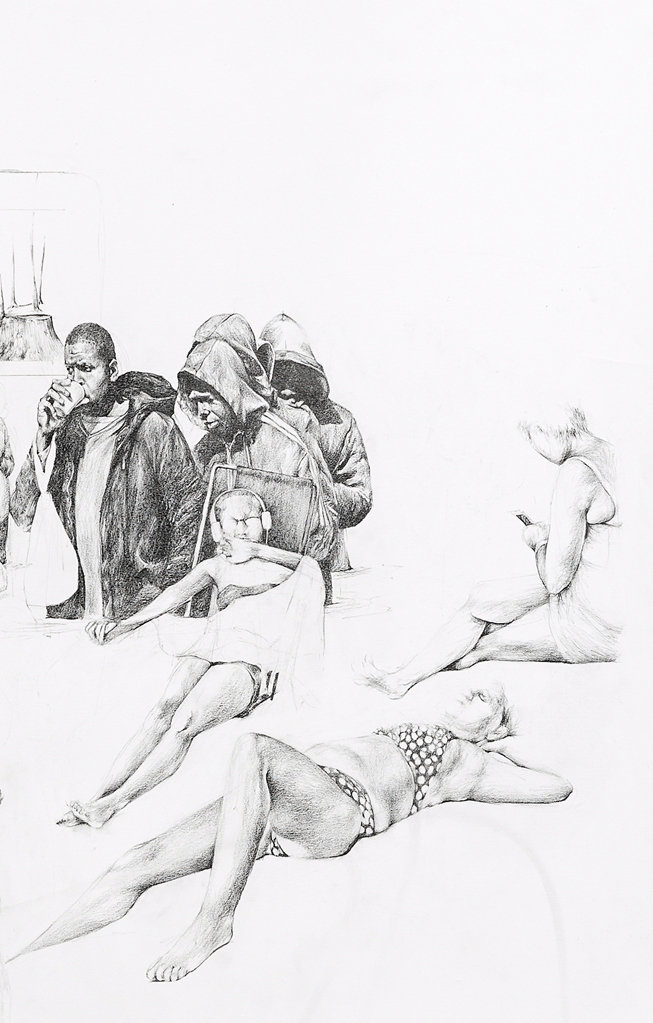

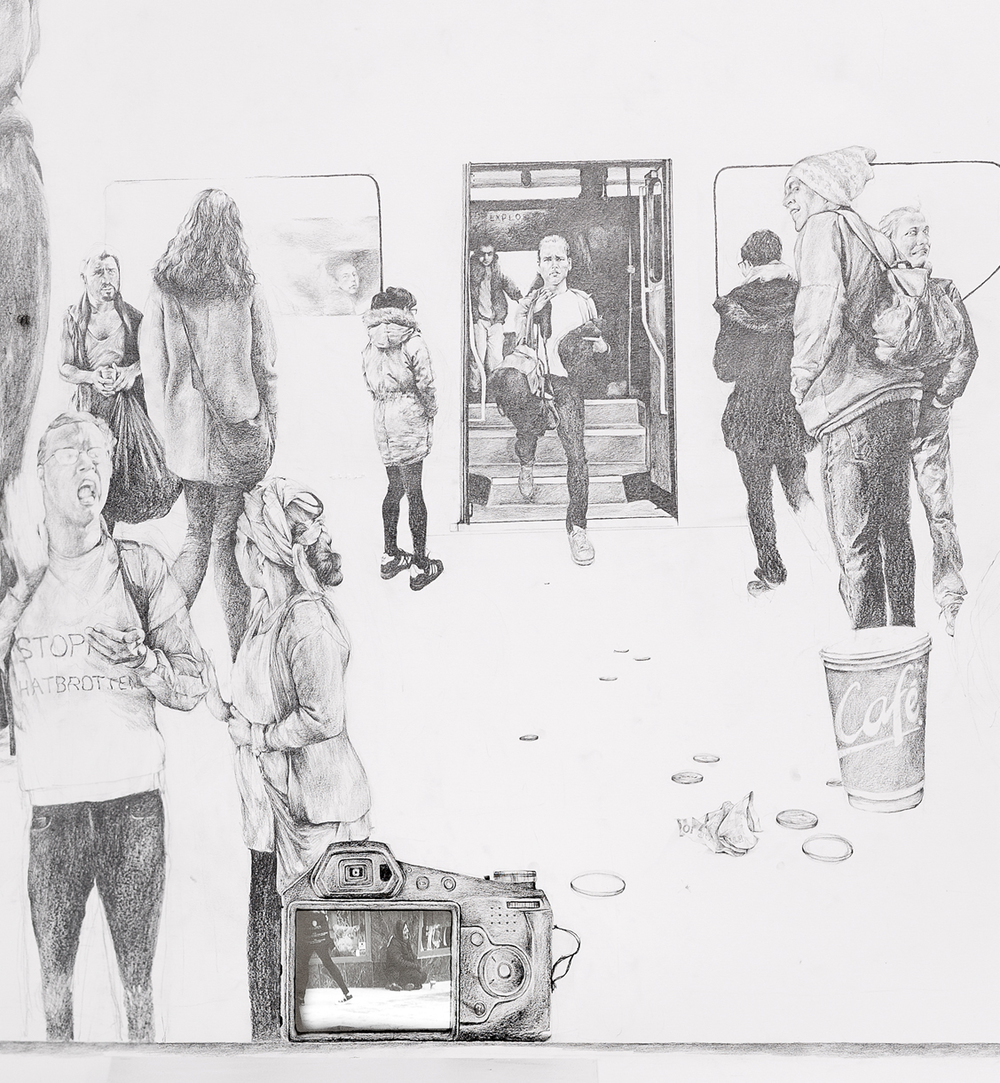

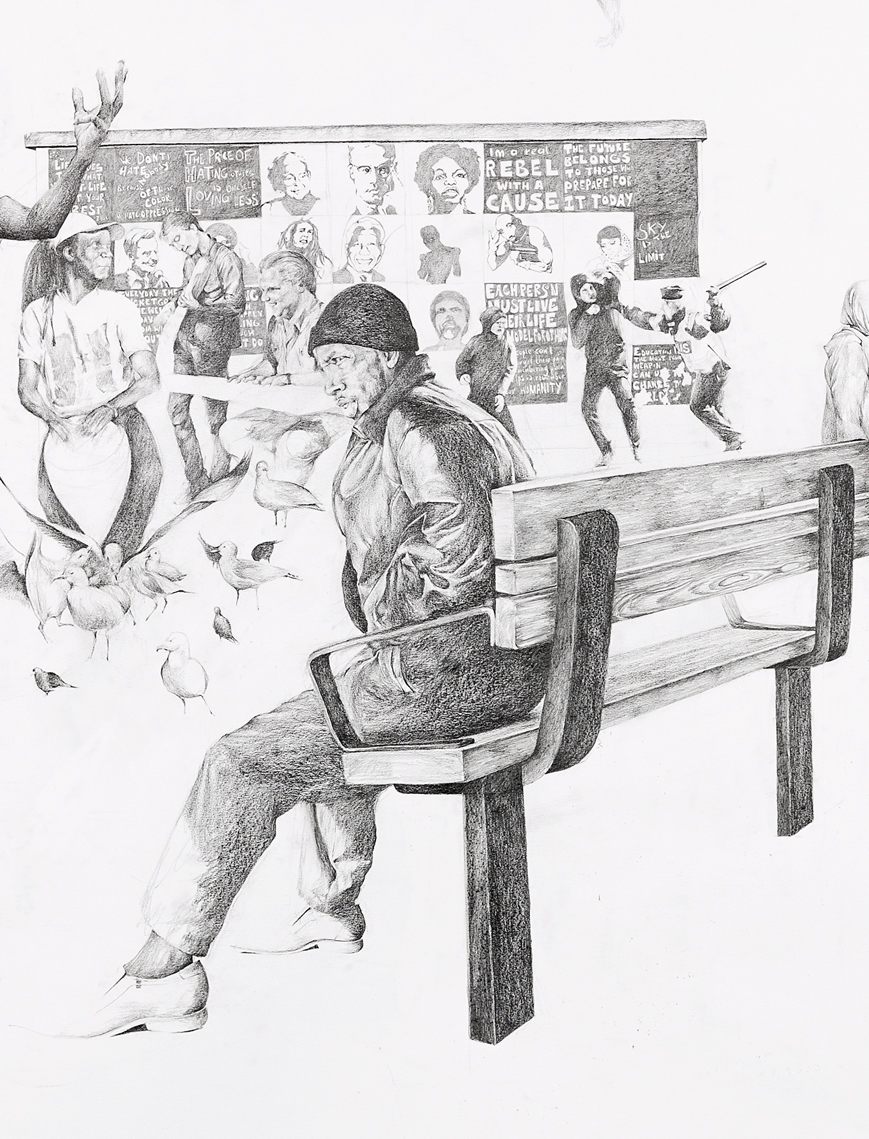

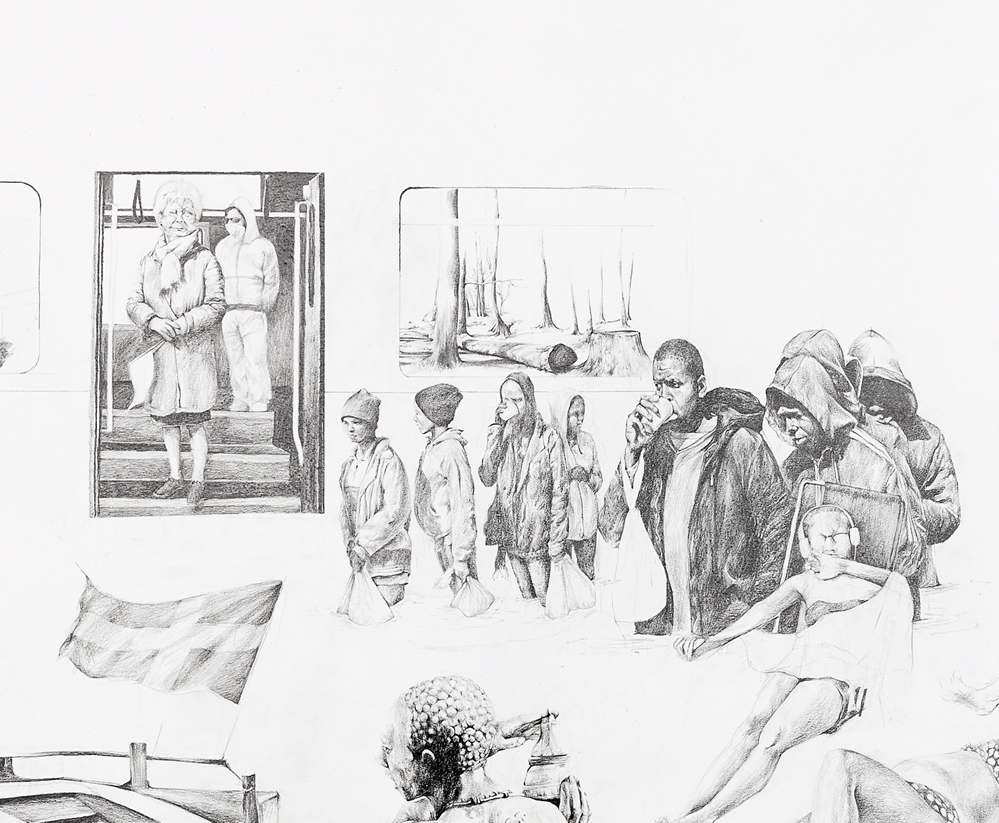

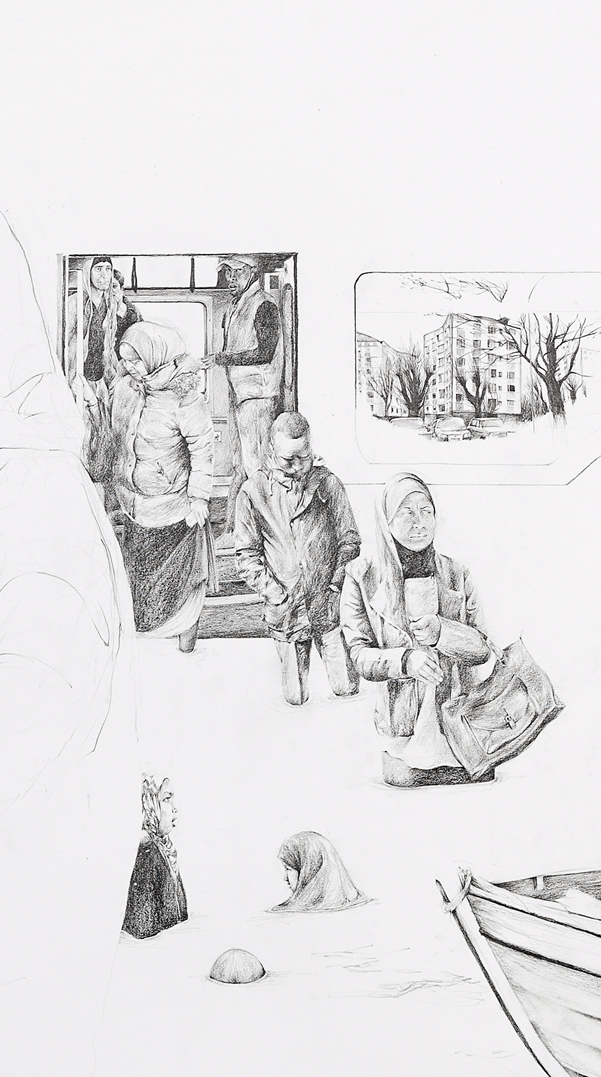

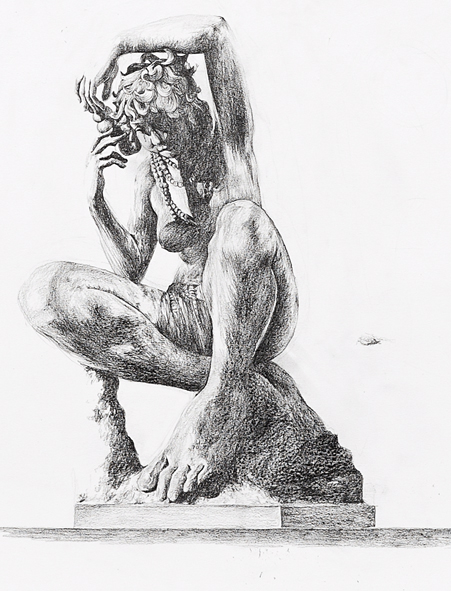

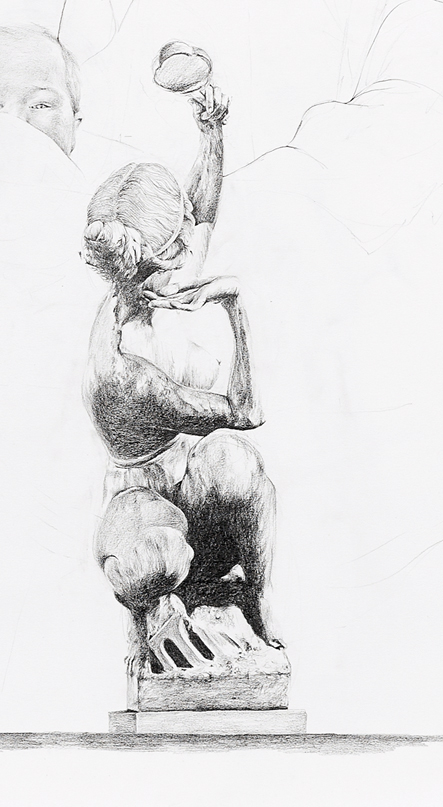

I decided to use my time at the Konstepidemin studio to make a drawing the length of the studio wall,

of a metaphorical journey on a tramline, starting at Linneplatsen where I was based, and journeying towards Angered, this predominantly immigrant suburb which I learned was established as part of an idealistic programme – indeed, vision – called The Million Homes project, which built social housing on the outskirts of the city predominantly to welcome the massive influx of both foreign workers coming to prop up the flourishing Gothenburg industry and refugees fleeing war-torn homes . I’m not going to attempt to theorise to you now, standing here in Angered as an outsider, an observer, why it is that societies in Sweden, a country known to have one of the most accessible asylum immigration policies in Europe, second only to Germany who has welcomed more but also has a remarkably larger population than Sweden, can have such deeply embedded segregation systems within its urban communities. We could talk about physical divisions, the space between the city and the suburbs, or about the infrastructures that exist, or don’t exist, within these suburbs, or how difficult it is to rent property in Gothenburg, or the problematic racial notions of what it means to be biologically Swedish, as opposed to inherently so. But I began to think about all these things.

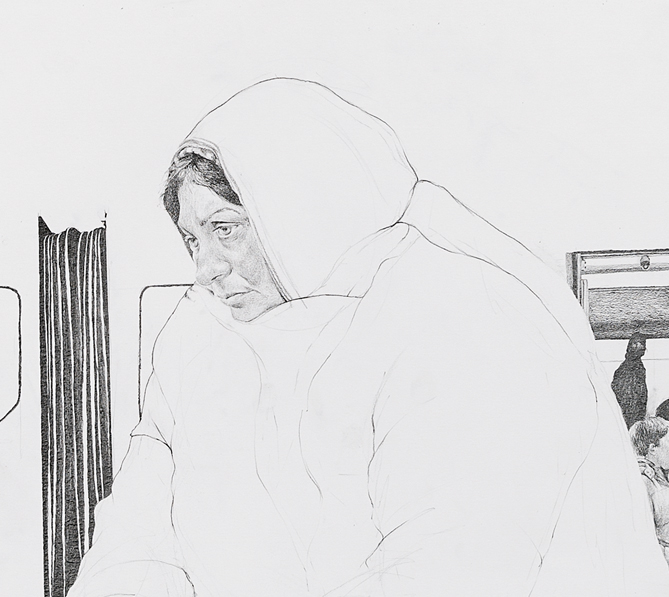

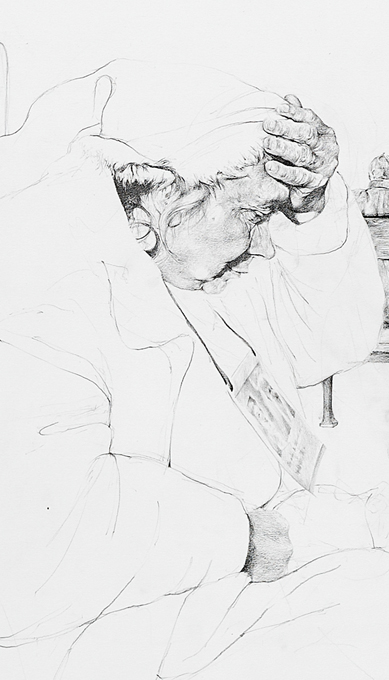

I embarked on this journey, documenting my observations as I traversed the city.

I took my camera and rode the trams, stopping to photograph things that caught my eye.

What I first noticed were these Roma women. Politicians call them EU migrants, some say it is a criminal racket, and certainly a very new thing for Sweden, but they punctuate the urban landscape,

in doorways, at tramstops, on highstreets, just sitting, silent, overlooked, and burdened.

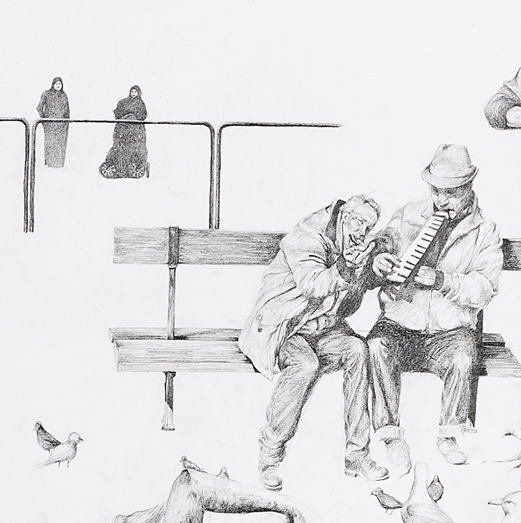

It’s interesting the little idiosyncratic moments that your camera captures that you don’t initially notice but that you can honour after through drawing. For example, at Central Station, which was built on a site that used to be the meeting ground for a vast community of Romany gypsies (though this has been written out of the official collective memory of the city), I photographed these two Roma fellas jamming on a bench.

Only later I realised that the dude with the harmonica is actually giving the finger.

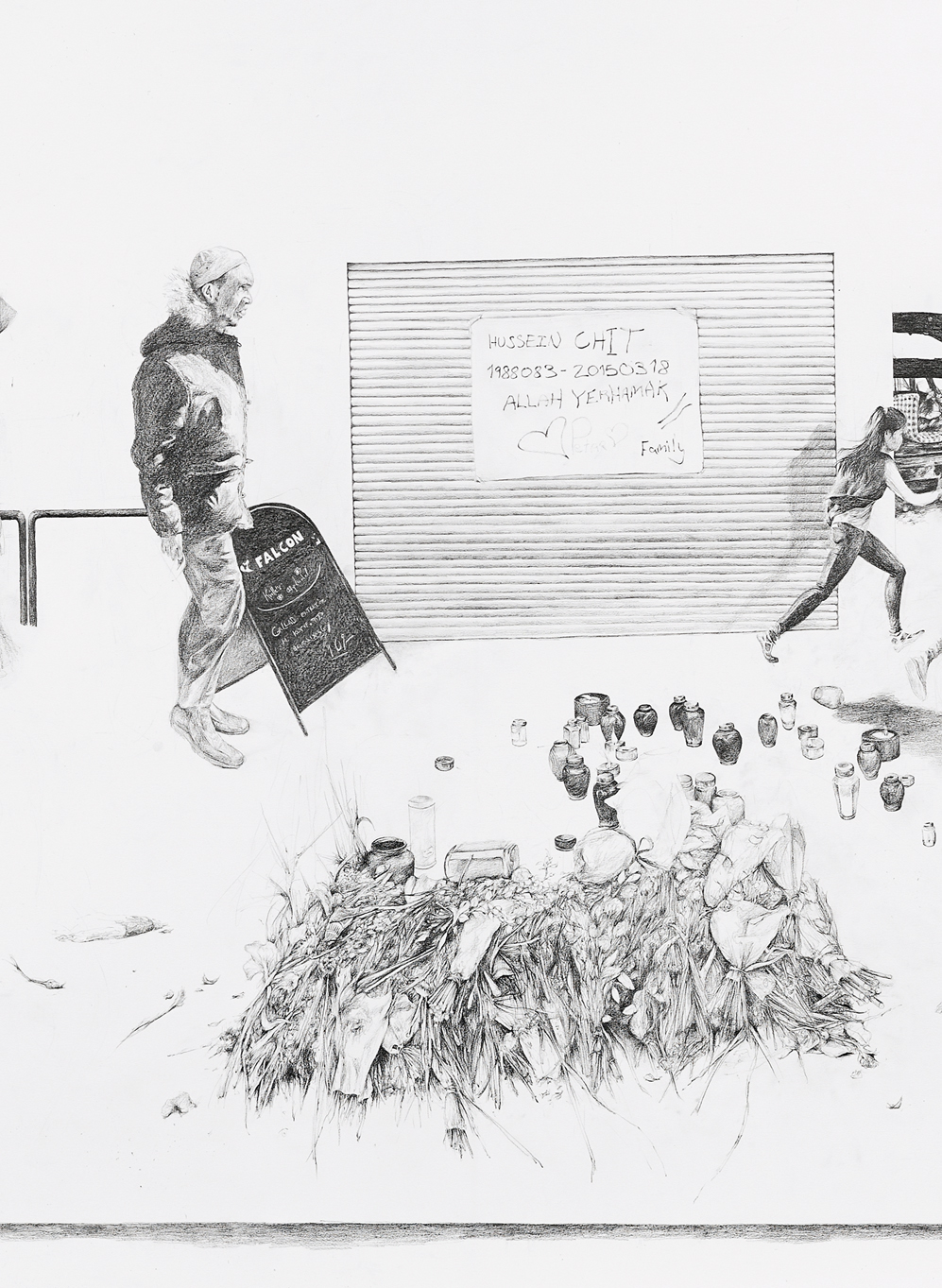

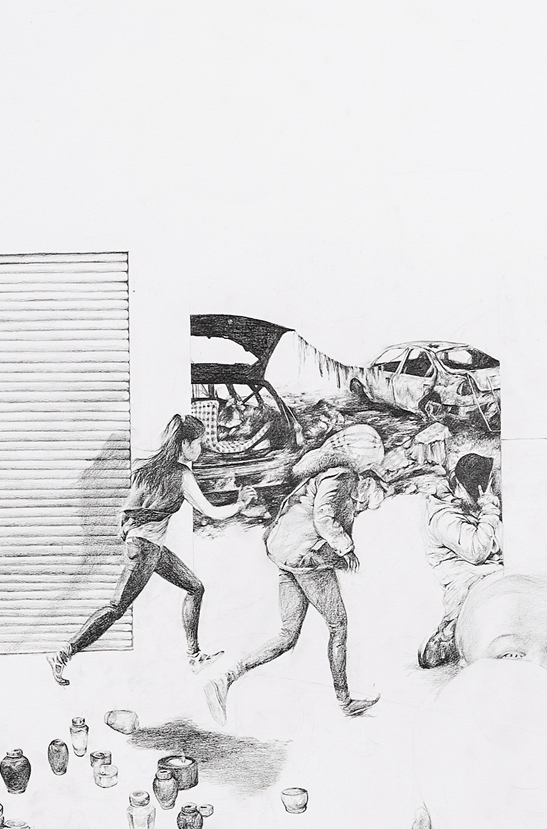

There had been a series of recent murders in the immigrant suburbs, and a tinder-gent from Cape Verde took me to his neighbourhood, where, on the 18th of March at 10pm, gunmen entered a restaurant where people were watching the Premier League, and started firing shots.

This was one of the saddest places I saw in Gothenburg. I spent hours drawing it, contemplating the loss of life in each pencil mark that built up to convey the decaying pile of abandoned flowers. The poster says: “Hussein Chit….1988083 to 20151803, allah yerhamak. Heart. Family.” There’s this thing about drawing from photographs that allows you to empathise. As I wrote his name, paying attention to each curl of each scribbled letter, I imagined who made this poster, and how they must have felt writing it. The ink of the fat parker pen was running out, so parts of the letters were more faint than other parts, and I imagined the writer shaking the pen in her hand, angry, confused, trying to will some life back into it. The case was written up in the press as ‘another gang related killing in the troubled suburbs’, and a lot of the middle class Swedes I spoke to about it sort of rolled their eyes as they brushed it off.

There were some stories I was told about that I later researched online, and added because they were important I felt to the tapestry of Gothenburg’s social narrative.

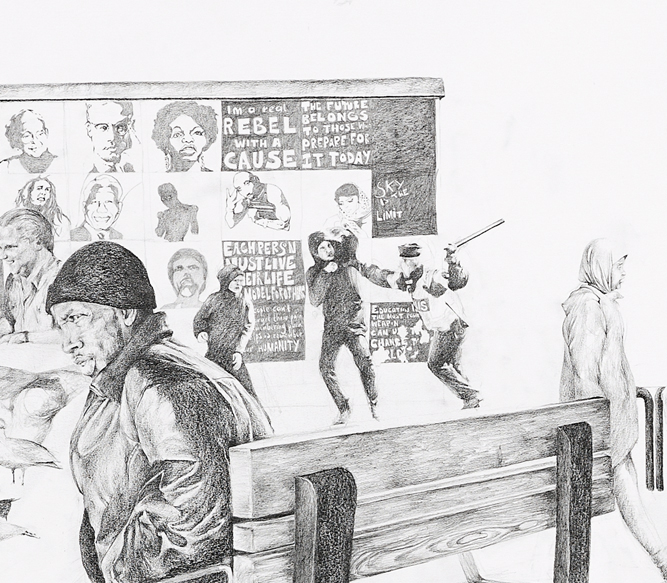

This was an image I found from a news story of a policeman beating a man after a skirmish involving two groups, one for and the other against the building of a mosque.

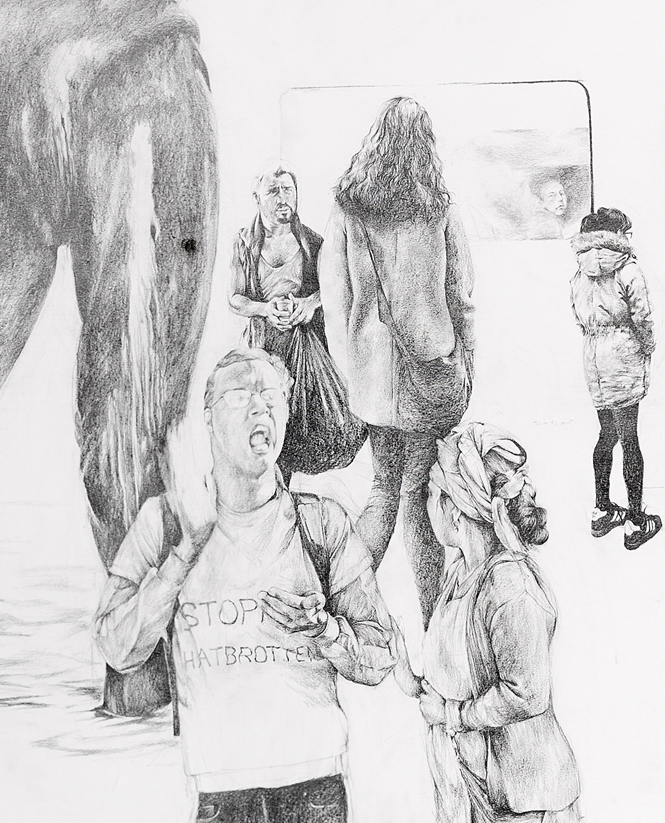

And this, this was a thing that happened at this market in one of the suburbs, where a Swedish man took his whole family and held a placard which basically said, “Hey! We are the Svenne family and we would like to meet an immigrant family.” He was sick of the segregation and didn’t want his kids growing up not knowing anything about the other people who shared their city. Apparently, the stunt was met by outrage, with nimbys calling him a bad father, and berating him for the danger he is subjecting his kids to.

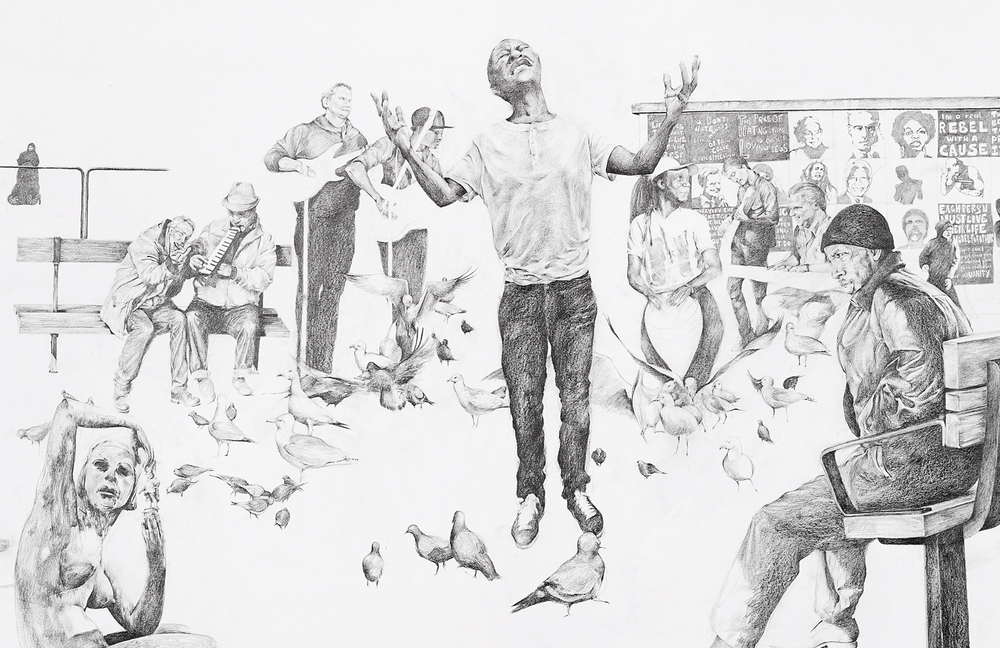

One night, I was invited to a gig at a cultural centre near my studio. It was a non-tinder-induced invitation, so I went, and I’m glad I did.

It was a jam session where musicians, both Swedish and from various African countries, kept arriving and adding to the beat. I’d been here about week at the time, only a week, and if it had been in London I probably wouldn’t have thought anything of it, but there was something so incredibly uplifting about this scene, how somehow, in music, all the bullshit segregation Gothenburgy stuff fell away, and everyone just danced. It might sound corny, but it filled my heart. So I placed them in the middle of my drawing to honour the moment, with the singer, Kele, a trumpeter from Soweto, in midsong. But is he singing, or is he screaming?

* * *

I slowly started to build up a picture of Gothenburg, which I rolled up once my month was up, mid-journey, knowing I’d be back in August to revisit it. I remember feeling that it was good to be back in London. When I delivered a version of this talk at the Disseminating Identities symposium at the V&A at the end of April, I closed by saying “I’m not sure if it’s only because one’s eyes are more in focus when in a new place, or whether Gothenburg is somehow unique – I have read in various places it being confirmed as one of the most segregated societies in Europe – but, having spent a month there, I read Baldwin’s essay with a truer sense of it. Which is a shame, in a way, since I realise that my upbringing has afforded me the luxury of not feeling the weight of the colour or the context of my skin. But, as Baldwin in his essay states, “People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction, and anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster.” “

After that talk, a dear friend of mine, the Kenyan writer Juliane Okot p’Bitek, came up and told me that you should never end a talk on someone else’s quote. If you do, it’s not the end. And indeed it wasn’t. Three months pass. On a London bus down Oxford Street, for the first time in my fifteen years of living there, a drunk man tells me to fuck off home. American police shoot innocent black people. Syria burns. Rickety, waterlogged boats carrying desperate people continue to sink in the murky waters of EU politics.

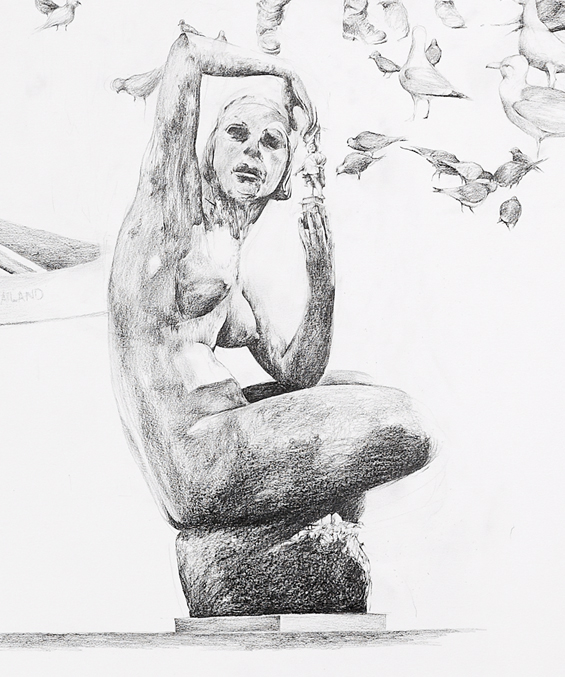

Images of waterlogged brown people and tiny children in red teeshirts who could be yours have finally started to lap at the shores of apathetic minds , shaking eyes open. Innocence all around us is dying. Our world, in so many ways, it is segregated. I arrived back at the studio at Konstepidemin in August, unrolled the drawing, and tried to find a way back in. It was strange being back in exactly the same space. Gothenburg was still pretty, still polite, ordered…warmer.

People were at their ‘summer places’ on the islands of the archipelago. But in Stockholm, fascists had plastered the subway with racist rhetoric, and people are mad about it.

Roma ladies still linger in doorways, but Romany camps are being arsoned and people are mad about it.

The Swedish Democrats are creeping up the polls, and people are mad about it.

Collective voices are powerful. We are all connected. While I was here installing The Matter of Memory, thousands of Gothenburg residents came together in Gotaplatsen, surrounding Poseidon, in solidarity with refugees. All over Europe, people have been doing the same. We all need to be active now.

I began to draw more urgently, speaking more directly than my initial observational meanderings. I began to break the drawing up into isolated mini-drawings, titling them and sharing them on social media, contributing them to the swelling collective voice of ordinary people urging their governments to do better, to be better. It became an integral part of the project.

Residencies are incredible things. The journeys that occur within them. As artists, they propel and ignite, they confuse and intrigue, they definitely change you. It is not lost on me, as we speak of borders and migrations, how easy it is for me to climb on a plane and come and spend months being resident in Sweden. No visas. No permissions sought. No red tape. My own mother, who by consequence of her birth, travels on a Kenyan passport, while her children enjoy the luxury of dual citizenship, cannot freely come here. In order to be here with me tonight, she had to travel to Dar es Salaam to the Swedish Embassy, with an invitation letter from GIBCA and another one from me, to ask them to grant her permission to come and see her daughter’s show, the one in which you can hear her voice, her stories, and see that drawing her daughter did,

(from The Matter of Memory installation)

of her mum’s feet, grounded.

This is an excerpt from an essay delivered as an artist talk at the Blå Stället Konsthallen in Gothenburg in 2015 where Phoebe Boswell was exhibiting Tramlines. At the same time, The Matter of Memory (2014) – her immersive installation exploring ‘home’ through her parents’ memories – was in exhibition as part of the Gothenburg International Biennale of Contemporary Art (GIBCA). The essay can be found in full at www.phoebeboswell.com.

[IMAGE-CREDITS]

Phoebe Boswell (b. 1982, Kenya), born in Nairobi to a Kikuyu mother and British Kenyan father, brought up in the Arabian Gulf, and now living and working in London, makes work anchored to a restless state of diasporic consciousness. Combining draftswomanship and digital technology, she creates immersive installations and bodies of work which layer drawing, animation, sound, video, and interactivity in an effort to find new languages robust yet open and multifaceted enough to house, centre, and amplify voices and histories which, like her own, are often systemically marginalised or sidelined as 'other'. Boswell studied at the Slade School of Art and Central St Martins. She is currently the Bridget Riley Drawing Fellow at the British School at Rome, a Ford Foundation Fellow, and is represented in the United States by Sapar Contemporary, New York. Her work has been widely exhibited: with galleries including Kristin Hjellegjerde, Carroll / Fletcher, and Tiwani Contemporary; art fairs Art15, 1:54, and Expo Chicago; and has screened at Sundance, the London Film Festival, LA Film Festival, Blackstar, Underwire, British Animation Awards, and CinemAfrica amongst others. She participated in the Gothenburg International Biennial of Contemporary Art 2015, the Biennial of Moving Images 2016 at the Centre d'Art Contemporain in Geneva, and received the Future Generation Art Prize's Special Prize in 2017, consequently exhibiting as part of the Collateral Events programme at the 57th Venice Biennale.