I must admit, I was incredibly selfish before I had my daughter. As many—too many other Dominican women and men—born and raised on the island, I didn’t give a shit about the environment. Why? Nobody else did. The government didn’t care. No one spoke about pollution, or waste; the word “contamination” was only used to refer to drinking water, and Haitians.

Then, Mía came. And the world suddenly was not only the place where we all live, but the land that would hold my child. It held the air she was going to breathe, the water she was going to share with her loved ones.

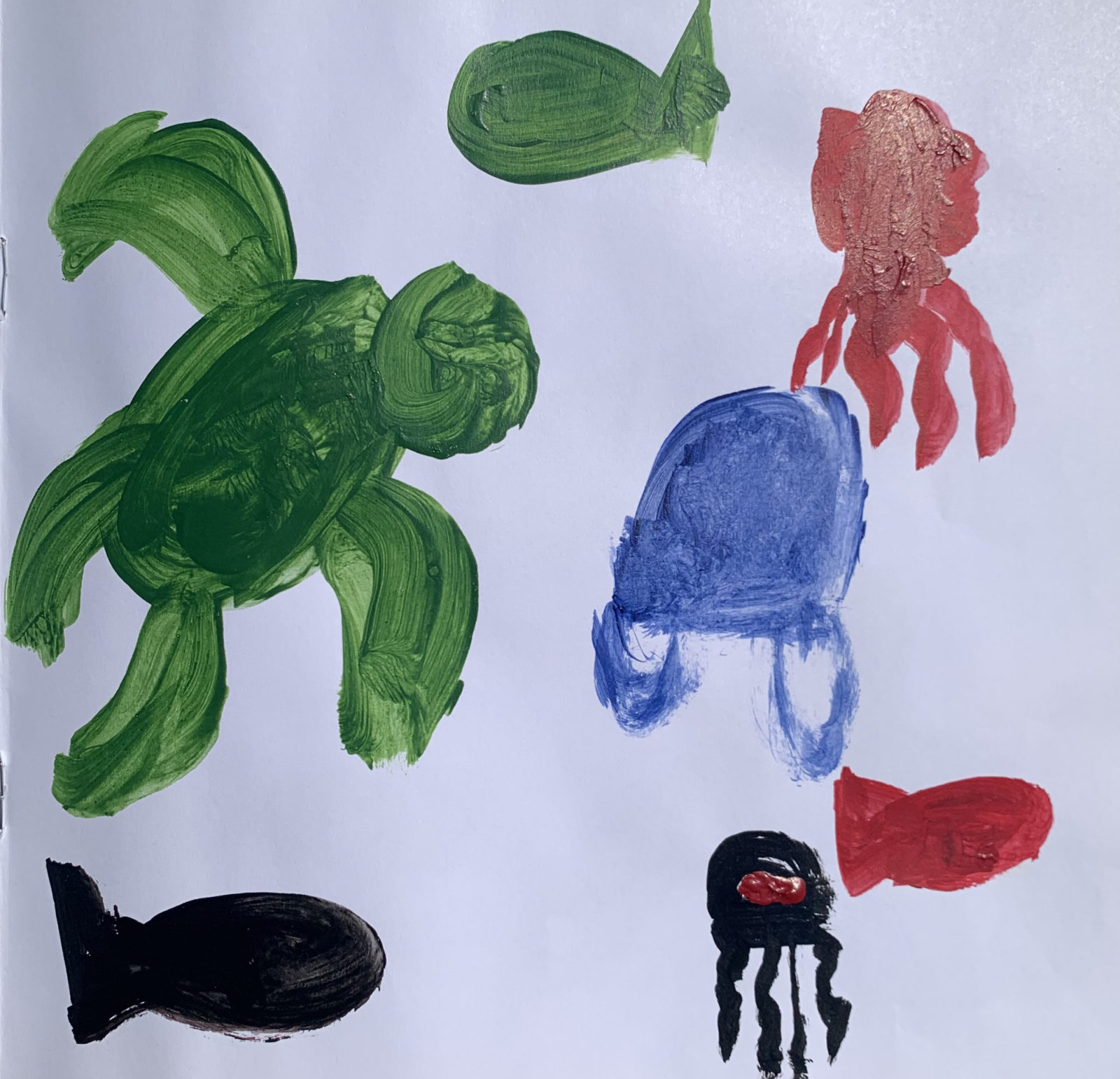

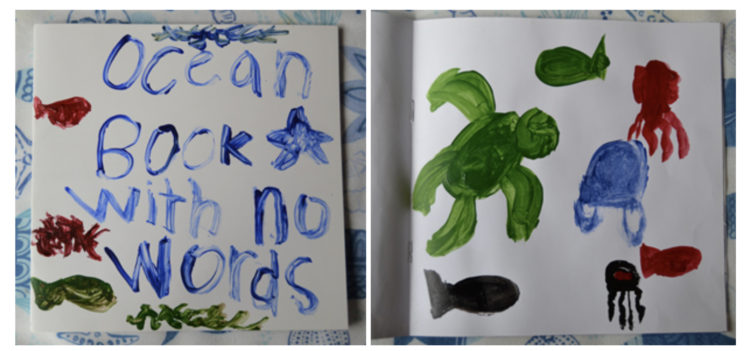

And then Mía turned three, and began talking about the sea, and the number of plastic bottles and bags we, humans, throw there as if there were no animals that could be harmed. And then she turned five and six, and all she talked about was how she wanted to live in the forest, with the trees, and her loyal friends the animals.

At six, poetry came; seven, she didn’t want to be called a human.

Humans litter

they hunt just because

air pollution

light pollution

they destroy habitat for no reason at all

global warming

they throw so much garbage in the ocean

humans suck

These were her words.1 She was enraged with our privilege and lack of consideration of other living animals—I would listen from a little corner and be ashamed—and her complaints went on and on.

“Do people throw garbage on their own homes the way they throw it on the streets?”

“Why rich people don’t make more machines that clean the oceans?”

“I don’t need any more clothes, Mamá,” she once told me, “I have enough. We are just making more garbage.”

Now I think twice before buying a bottle of water, while the memories of the once affluent Río Jaya, back in San Francisco de Macorís—my hometown—drill holes in my conscience. I think twice before drinking from a straw. Sitting in the Malecón, in Santo Domingo, is a more depressing though than the dream of a returning emigrant—the water is no longer sky blue; the shores of my island are covered with garbage (unless the beach belongs to an international hotel, and then they make sure the beach is clean for the tourists to enjoy). Going to the supermarket without a tote and shopping fabric bags mortifies me as much as inserting a tampon in my vagina.

And she, my Mía, is so angry still, and the rolling in of her preteen-self reminds me of this, and her need for naming, and climbing and talking to trees remind me of this; and more than my daughter, she is the mother, the voice of reason. She understands Mother Earth. And Mother Earth is angry. Why wouldn’t She be? With a womb full of evolved Homo Sapiens, capable of flying to the Moon and beyond, modern gods capable of communicating at the speed of light from one side of the globe to the other, but incapable of taking responsibility for neglecting and harming the only home we have.

Today my daughter is ten and, through her words, her poetry (her very political poetry), activism, and observations, she continues to teach me about anger and love: anger for what we fucking selfish humans have done to destroy this planet and our blindness and lack of desire for taking a step; and love for Rubie Catillac, our cat, our chickens, which I would not name at this time, Angus and Ottis—our neighbor’s dogs—and every other animal2 and plant alive. If it were for her, this house would look like Ace Ventura’s.

I wish I could tell you that I have done more than writing a few children’s stories about this topic, that I have a plan, beyond my still selfish conscience, on how to be of greater help; that my rage and my sacrifice can compare to those of my daughter’s, and so many other brilliant youngsters, but all I have to offer is this everlasting shame, this body and heart that will forever support my daughter’s wrath—because I, and you, didn’t care.

– – –

Endnotes:

1 When I told Mía I wanted to quote her in something I was writing, she didn’t like the idea of me talking about her “intimate” things; then she read this piece and she seemed pleased with the outcome. She added, “People should know about this and change, with or without children.”

2 The first children’s book I published titled Mía, Esteban and the New Words (Alfaguara, 2014) was born after seeing little Mía hugging and kissing the stinkiest sheep we saw in a town fair.

Kianny N. Antigua is a Senior Lecturer of Spanish at Dartmouth College, and an independent translator and adapter for Pepsqually VO Sound & Design, Inc. Antigua has published twenty-four books of children’s literature (seven by commission), five of short stories, two collections of poems, an anthology in two languages, a book of microfiction, and a novel. She has won sixteen literary awards and many of her texts have been included in anthologies, literary journals, newspapers and textbooks. Some have been translated into English, French and Italian. She is the translator (Eng./Spa.) and the audiobook narrator of Dominicana (Seven Stories Press, 2021), by Angie Cruz; translator of the children's novel Lucky Broken Girl, by Ruth Behar; the YA novel Never Look Back (Bloomsbury/Audible, 2022), by Lilliam Rivera; and the picture book Plantains Go with Everything (HarperCollins, 2023), by Lissette J. Norman.