Anthony La Pastina: So let’s begin this discussion with your ideas about borders. I’m particularly interested with your newer works where you built structures with metal.

Paolo Piscitelli: From very early on, since 97/’98, my attention was on marginalized spaces. In Europe, there are lots of stinging nettles growing on the borders, on the streets, and outside the gardens. People usually try to get rid of nettles, because they’re weeds, but my intuition was to cultivate them. So when I first started working in Texas, I did an animation called ‘Some Prefer Nettles’ that simulated shadows of nettles growing and occupying the space. I projected these images in the space, not on a screen, taking over the space itself with this idea—visually it was almost like a science fiction movie, with this huge plant—but really I was also drawing a connection to the discourse around immigration, where it seemed immigrants would arrive to the U.S. and spread out in an invasive way.

La Pastina: So the idea of the crossing of borders is something you were very aware of while working in Europe? The nettle became this metaphor for crossing. How did Texas play a role in this idea? Has Texas changed your work at all?

Piscitelli: My work did change in Texas, but not for political or social reasons. More because of the landscape. The landscape changed my perception, even when thinking about workers. Because here, (TX) you’re always in a car and you don’t really have contact with people so when I saw workers on the street they were part of the landscape, you know? It’s like they’re some sort of exotic animal that are working along on the streets, but you don’t stop the car to talk to them or have any interaction. In Europe, it’s very different. We don’t just have a visual interaction, but people really get in the way of each other, because the spaces are smaller. We are obliged to talk or to enter into physical contact.

La Pastina: So, with this idea of the laborer or the worker as part of the landscape…. I have seen that you have done a lot of work that deals directly with labor captivity, of working and the intensity of labor or the limits of your own stamina. How do you tie your work with this presence of labor or the presence of the border, the crossing of the border—because your work now, I think, has moved in a political direction.

Piscitelli: I think my work was always political, but it’s probably clearer in my newer works because the subject is more focused. For example, I’ve always been interested in the way ants and termites “work” and the idea of a collective brain, and how they have different roles and connect materials to create the organism where they live, etc. So I read a book where this researcher was trying to understand how when the Queen dies, all of the termites immediately stop working. He wasn’t able to figure out how this could happen without any signals that he could recognize between them. In a similar way when I performed on video a series called “Labor” I used my energy and my stamina and my hands to try and connect myself with this collective brain. So in a way, I’m always using myself, putting myself in a bigger process, trying to participate in a larger event. And so the idea of labor/my labor is interesting when I think it as a collective work and eventually with one end result.

La Pastina: Remember the surrealists had this idea of working in stream of consciousness? In a way, your work seems to have a dialogue with this stream of consciousness, generating this work spontaneously. There is an idea, there is a process that you are following but there is also an attempt to blank and free your mind of any information, just focus. It’s very Zen.

Piscitelli: I have to train myself daily because it’s an intense discipline to unlearn everything, and to be in a state of no mind and trust, so I am able to listen. My work is just a tool for me to understand what’s happening around me. My work is a way to investigate the reality, and of course here in Texas, the reality and the space and the political issues are different than in Europe. So, I changed my tools a little bit in order to understand better what’s going on here.

La Pastina: But, I think the work you’re doing right now is clearly the one that speaks, at least in terms of Texas, more specifically about borders and this idea, –and there’s a beautiful piece that we definitely have to have a photograph of, of the glove and the word “Nord” — and so in your work you have this very clear idea of labor moving north and the north as a destination for labor. Talk to me about the genesis of this work. How did this work come about?

Piscitelli: I was trying to underline, the value of labor no matter if you are paid well or not. Labor is moving people around the world and creating a lot of new opportunities. And so, I made this work where a used glove, filled with paper-mâché, is nailed onto the wall, and under it I wrote the text “Nord” with pencil. Labor is the real orientation for human beings; in order to find a 45 new condition where they continue to labor and to have a life and to think. Now immigrants move north, or west, not only because there is a possibility to work, they move here because they see that we live in a richer country, and that they assume we and possibly they can have a better life.

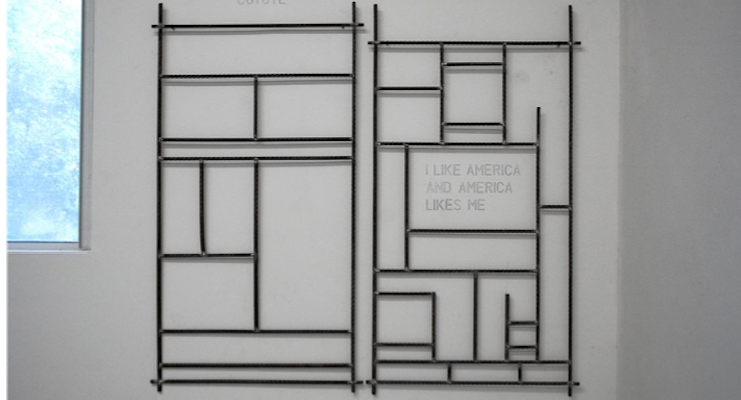

La Pastina: I’ve been thinking a lot about your work “Out Of Print” where you use the newspaper grids. Because in a way, they become borders as well. As borders they make a commentary about how we relate to news. There is no negation, no interrelation between one story and the next. And in reality there is an interconnection between most information, news, etc, a causality, relationships, power dynamics, etc. But the newspaper, when you just look at the grid without the content, you see the artificiality of it all.

Piscitelli: This work could be read as an homage or a monument to the newspaper. So that’s the work idea: to take the layout of the newspaper, empty out the content, and just to look at the plan. It’s like a map of a plan of a house. Like Corbusier would say, the plan is the generator.

La Pastina: But, you could also look at it as the archeology of the paper. Suddenly what you have are the bones or the basic structure and the content has faded away but you still have this memory.

Piscitelli: Exactly! In fact the last work I did using the grid of the newspaper, “Coyote, I like America, America likes me,” is made of rebar a material used in construction that one only sees at the very beginning, before it is covered with the concrete. But that’s really the structure that makes a building safe. The newspaper grids work in that way as well. In the same way rebar holds a building up, the layout houses the content.

La Pastina: I see with the gloves it’s also the case. You are appropriating used gloves from workers, real workers, real gloves, they have a memory of labor, they have a memory, you could argue, from the scent, from the materials that were used, from the scent of the person. So they are very physical, very embodied elements of the work. But, you are moving the memory of those gloves into paper and to drawings through a very meditative process. So, I think, again, the material for you becomes very important but you are sort of working with the memory of the material, the memory of the original material. Like with the newspaper, you are working with the memory of the original grids.

Piscitelli: But really the form is as important as the content. It is what will remain. I believe that the moment of the conceptual art as just a declaration is finished. That what’s exciting is to produce something that reflects the experience by the artist, and also something that the viewer can perceive, not just through the visual language, but viscerally. So, when I had all of these used gloves in my studio, gloves that I collected from laborers in Texas with the help of Daniel Peña, I watched the gloves for a long while and thought that they are like shells without anything inside, but there is a sign, there is a story itself written on these gloves. And for me it was important just to spend time with that object and watch that object and the unique way to do that, in a peculiar way, was to draw them. Every day I made a drawing of a different pair. So this composition, series of drawings is called “107 Days/100 Drawings” with the reference to the first 100 days of the new government [laughs].

La Pastina: [laughs] Or the film of Pasolini.

Piscitelli: [Laughs] Yes, but it was 120 days… So, for me it was a practice for every morning, or in the evening, to take a pair of gloves, or sometimes a single glove, because not all of them are in pairs. I started to watch them and make a drawing. I didn’t want to use the real object and I didn’t want to transform the real object in a reliquia and I didn’t want to take a photo. So the unique linguistic solution for this was to make drawings. It’s like, for a writer, it could be an exercise: For a writer to look at a pair of gloves and for each pair of gloves to write a short story.

La Pastina: When I think about the gloves and I think about the work, I immediately think about migration. But in reality, not all of the gloves came from migrants.

Piscitelli: Yes, exactly.

La Pastina: But it seems that in our contemporary life, in our contemporary society, labor is associated with migration, labor is associated with exploitation. Because in Western Europe, the United States, and Canada, working is associated with third world hands. So, your work can be read as a reference to the U.S./ Mexico border or the Africa flow to southern Europe or the Turkish flow to Germany in very different contexts. And so “north” becomes this mythological “nor th.” You could even say like finding your north, finding your direction. So, to me, this work has multiple connotations of crossing not just a physical border but this border that has become like a political marker. Like moving north means achieving the American dream even if you are in Europe. It’s like achieving this idea of prosperity. Good healthcare, good education, possibly good for your kids, which in the past, in our parents’ generation, was moving south, moving to the new world. So, to me, it’s very interesting to think about how labor has shifted in the last one hundred years.

Piscitelli: Yes, it’s unfortunate that when people see a sign of something associated to hands on/hard work it’s attributed to someone outside their immediate world. And when people say, “there are no jobs,” etc. there are jobs, but jobs few want to do and many of those jobs, often underpaid, and physically challenging are performed by immigrants. The thing that’s interesting about the gloves, is that they are a remainder of the hands of the ghosts/workers. So even if many don’t want to work with their hands anymore, expecting someone else to do it, the end result is that immigrant workers here and abroad are like ghosts shaping our world through their labor.

La Pastina: But then it leads to the critique, no? Because then you have the backlash against immigration you have the backlash against immigrants in Europe or here. In Europe the anti-Muslim or anti-African sentiment—the racism. But, I’ve talked to you about it already but when I saw the glove with the paper-mâché inside coming out you know that’s how I was reading it. There is a level at which the glove becomes the contaminant, like it’s diseased. So, at the same time the glove is what keeps the western, modern society functioning, these are the people who are cleaning, these are the people who are picking the fruits and the food. They are also contaminating the culture. And the glove in that sense, the exploding, becomes like a sense of a diseased body that is contaminating modern society. Borders become metaphoric in many ways. You can’t take it back. You can’t eliminate the possibility of the labor. But in doing that, you are acknowledging that your culture is going to change.

Piscitelli: Yes, our culture is going to change no matter what even if we don’t want to admit that it will. Immigrants are shaping our world. Even if someone thinks “okay, we design our space, let someone else build it,” that idea can’t work because the design is one thing but it’s the single person’s hands on labor that is shaping and putting energy into that plan; there is an entropy in any material that is worked by the hands of someone.

La Pastina: That’s where I think the dialogue between the gloves and the newspaper grids and the texts that you are using, especially the one that refers to Joseph Beuys, becomes a metaphor for the borders, the frontiers, and the spaces that are very well marked.

Piscitelli: That work, referring to Beuys has the text: “Coyote” written outside of the newspaper layout. And inside, “I like America, America likes me.”Which is a reference to the title of the first show of Beuys in the U.S. As a performance, he lived with a coyote in a gallery space. Then of course I started to think that “coyote” has a different meaning for the immigrants who are crossing the border, it is the name of the person who they pay to help them cross to the other side. “I like America, America likes me,” is really the voice that is attracting the people from the south to cross the border.

La Pastina: But, at the same time if we think back at Beuys’ performance, I mean it’s incredible! How do you read that?

Piscitelli: I think that it was a way for him, in a similar way that it is for me, to negate or perhaps create a new relationship with this country.

La Pastina: What is the title of the show you are doing with the gloves?

Piscitelli: “Hands On.” The core of it is simply labor.

La Pastina: So for you, working as an artist is almost a survival need. You can’t think of yourself doing anything else?

Piscitelli: No. I did a lot of—when I was younger—a lot of different jobs but I also did a lot of art. Something happened at a certain point in my life that even when I had some doubts, people around me were telling me that the work I was doing was important. So, being an artist is a position in society that is on the border probably, but then you realize one day that people need you/me there.