This is what my erotomania has done to me. It has made my life the dreams of a delirious sick person or an unfinishable letter to you—one I cannot even start because I am so caught on my view out the window. And yet—despite the fact that I do not know what to say to you or about myself—my life is richer than ever. This crush has unspooled imagination in the most exciting ways. I am giving myself nodes preparing a Sharon Van Etten impression, just for the pleasure of it. I am reading Lyn Hejinian and it is making sense. I am having the most amazing dreams. In one of them, I am introduced to Megan Thee Stallion at a bar. We hit it off immediately. When the conversation comes to a natural pause, she remarks she has enjoyed the evening and calls me “dashing.” Dashing! I wake myself up smiling.

* * *

But how to construct a text to a woman in such an epistolary era as ours?

“In some ways, I know deep down I’m straight by the fact I want a phalloplasty to be able to fuck you. And maybe if I write my feelings into something just a bit longer, I may be able to win a Lambda or some literary money in order to get it”

I clear the message body. It was Schlegel who wrote that “Nothing is more contemptible than sorry wit.” I really find him so inspiring.

I draft and delete: “Don’t you think solar eclipse glasses are an experiment by big ophthalmology?”

The science of eyes, of sight. Looking out into the bright-darkness of the covered sun, receiving what I am imagining is a Lasik vivisection—which is a thought I’d like to share with you, although I’m not sure it’s sufficiently witty yet, and so I let it be—I ideate. Perhaps a kind of Junie B. Jones-style message? and I think about a message that might comment best on the state of the world, the eclipse a kind of commentary for all these earthly discourses, these pieces of leather that form the sick bit upon which I chomp. Even though me and my coworkers’ perceptual apparatuses are all being phenomenally expanded to the point of total clarity, even if we are uniquely placed to have some insights into the heavens, we are still all thinking about the human condition, I imagine. Our hovels, even. Except I am actually thinking about the feminine condition, and that I do not care at all that we are under the same gray sun, our pupils turning into the heads of pins, transmuting like those of curious goats. I don’t find it romantic at all. Perhaps I should write what I see.

* * *

The eclipse’s surround. An eerie quality of light, the premature dimming of the day’s stage. Driving home from the college where I work as a secretary, I see young people looking directly at the sun. Some fearlessly, nakedly exposing their eyes—that unique nervous organ—bare to the sky. I find myself inside instead of out, feeling that perhaps regular estrangement from nature is not so bad if we get to have these special moments of oracular and anticipatory blindness, together.

* * *

Driving gives me time to come up with the perfect messages.

“How was your day in the symbiotic morass?”

“Short story idea: woman who gets extremely horny reading Lacan”

“Schlegel said that ‘sapphic poems must grow and be discovered’—what do you think? also, ‘grow’ before ‘discovered’? order seems off right?”

I hit the curb really hard and turn off a crime podcast. After parking, I walk towards home.

* * *

Schlegel: “Women are treated as unjustly in poetry as in life. If they’re feminine, they’re not ideal, and if ideal, not feminine.”

* * *

At home, I talk to my neighbors on the porch. A bit about the weather, the pesticides I put in a bucket in the backyard for the mosquitos, the fact that the landlord is selling the house. The color of the sky does not inspire more description, although the coloring is suggestive of something odd in its history, reminiscent of the wildfire smoke that had settled the air quality earlier last year.

In the place of the political and structural discourses that had dominated the issue previously, a new form of respiratory orthorexia traveled in on the breeze. People were buying air purifiers and wearing masks. They were taking off work and staying inside. Back then, an ex called and asked if he should be concerned about moving down the street from some kind of waste dump in Brooklyn, something we would have never thought twice about until we heard all of this constant horrible stuff about the air. We both perversely tried to take some comfort in the fact that there is an elementary school even closer to the dump than the apartment at hand. I think, deep down, I just did not want this to be a problem. I encouraged him to at least see the place and then I smoked a cigarette outside, knowing that the disease I could get from this particular one was intensified by the blazing, the killer wind.

* * *

Michèle Montrelay: “I never say to myself: ‘I am writing as a woman, I am going to get this message across better than a man, or not as well.’ What is important, I repeat, is the unconscious.”

* * *

I like how they translate Marx, how they make him say that it is the “sensual” or “sensuous” world. It is not impossible to imagine Marianne Williamson saying the same thing, for example. That’s an appreciable vulgarity. And there is something erotic to the world as it is perverted for the purposes of information, and even to the way that information might be transmitted. To stay merely in the moment to moment of embodied experience, in all its temporariness and solitude, is dull and disordering. It disappoints. It’s why the genre of poems about plucking out one’s pussy hairs, written in English but with the air of translation from the French, has been a major contributor to cultural mortification. But to lend one’s sensuous black box to language, this might be worth going on for.

* * *

Walter Pater: “The service of philosophy… towards the human spirit, is to rouse, to startle it into sharp and eager observation. Every moment some form grows perfect in hand or face; some tone on the hills or the sea is choicer than the rest; some mood of passion or insight or intellectual excitement is irresistibly real and attractive for us,—for that moment only. Not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end.”

* * *

What would it even mean to write a text like that, one that could rouse or startle a woman? I pace, I percolate. Should I tell her about how I recently saw The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and have been admiring the way it alchemizes the shrill laughter of desiring, beautiful women, transfiguring it into shrieks at the edge of death? That’s what I would like to tell her about, but there is such a thing as too startling. It’s not about the fruit of experience.

* * *

Of course it’s impossible to be fully in the sensuous world. One hears about people who get too far into spirituality courses and celibacy and begin seeing things for what they really are all the time. It is the veil between real life and sense data that keeps us observing. If one gains direct access, they also lose observation—a loss that occurs in the real.

* * *

I walk inside and sit down at the kitchen table to think. But there is only so much desecration I can take.

At the very moment of fantasizing about the various ways my continued desecration would manifest, NPR begins the assault: a segment about how young people are using generative AI to write each other love letters. When the radio broadcasts your thoughts—this is the exact kind of psycho-structural vulnerability that love creates, the kind that threatens observation. Well it’s a good thing I am being defensively mindful. My kitchen knick-knacks are in perfect order. The little cats are swarming the surfaces, all of the devices and lights are humming in complementary frequencies, and my sweatshirt snugs correctly and where it should, at the wrists and neck. These evidence my observational abilities are intact—the veil sheathes, relieves the real of oversaturated potential meanings.

But the cosmological thoughts are still beckoning—the magical thinking creates a salaciousness where before there was nothing. God destined the creation and sending of this text message. God created this NPR broadcast, and God affirms my adoration by adorning it with a brilliant (but still, secondary) goal—to stop AI with the power of letters.

* * *

Lots of people want to stop AI with letters. I recently attended an academic conference where many people talked about what might be good about AI, what we might be able to steal back from the machines. After yet another talk about its possible usefulness, an audience member quietly pushed back on the entire weekend’s perseverations. Straining, she named the dangers of the proposed AI collusion. She spoke about the environmental devastation that was looking us right in the face, that we were literally producing. She described how we had a unique opportunity, at this juncture in time, to really actually do something. To stand up and say no.

AI is a hot, demanding object—it is a tenement of dry wires connecting devices, a mechanical bricolage more like Aronofsky’s Pi than Gilliam’s Brazil. It needs a septic sip of the pesticide bucket. It needs to belch gas into the sunless sky.

The protestor in the crowd invokes Schlegel, who writes “Like animals, the spirit can only breathe in an atmosphere made up of pure life-giving oxygen mixed with nitrogen. To be unable to tolerate and understand this fact is the essence of foolishness; to simply not want to do so, is the beginning of madness.”

* * *

The German critic and philosopher Schlegel is described as a cunty child who became a genius and died a proselytizing tradcath. He is saintly in this way—how real that kind of trajectory is, how honestly reactionary to one’s own developmental movements. Other people did not like him because he was very annoying. He writes, for example, “You are not really supposed to understand me, but I want very much for you to listen to me.” He hardly ever finished any of his writing projects. Even his lauded fragments—that mega-pith of notes, musings, and reviews scraped from notebooks over years—were (supposedly) ultimately intended to constellate a solar system of literature, and give better shape to all of literary thought. To prepare us to apprehend the word. Each fragment, he wrote, must be a “miniature work of art,” and had to “be complete in itself like a porcupine.”

He was too needling, his thoughts too spikey to generate a total theory of everything. Schlegel’s fragments are authoritative. Naturally, he is a hater. This is kind of funny, because most every reader and critic—among them Kierkegaard, even—despised his novel, Lucinde: Confessions of a Blunderer. Semi-autobiographical, horny, preachy, and of course—unfinished—it is considered a truly terrible book in most respects. It begins with a lover’s letter to his sweetheart. At first, he excites himself with the promise of sharing his history—sharing of his very self—with his desired object. He goes on, glowing in anticipation of then producing a radiant account of the couple’s shared life. But he makes some insane detours. First, he gets distracted from his task by looking out the window. Then, he discloses that even though he has been writing prolifically, he basically messed up the order of the pages so badly that he is just going to present all of this testimony as “dreams.” He is just going to do the best he can. The protagonist is thus forced to claim an “incontestable right to confusion”—and he transforms his executive function problems into an intervention on genre. He promises to disorder the novel, to give it an arrhythmia. Only this way can he accomplish the real task of writing—to collect and record that observational data necessary for the elaboration of “the loveliest situation in this most beautiful world.”

* * *

It does not seem that people are finding women’s private philosophical notebooks. Or perhaps they are just being published as different genres.

* * *

Schlegel loved Diderot, who loved Sophie Volland. In a letter to Volland, Diderot writes: “Look at the circuitous paths we have taken. The dreams of a delirious sick person are not any more heteroclite. And yet, just as nothing is disconnected in the head of a dreamer or a madman, everything holds tighter likewise in conversations, but sometimes it would be quite difficult to reconstruct the imperceptible links that held so many disparate ideas together.”

* * *

Perhaps I cannot write you because I want these associative links to stay mysterious. How will I explain where all of my potential communications have sprung from? I desire bond, not bondage. And perhaps, at times, the links are too perverse to elaborate with more interaction. In the corner of a loud and wooden bar, I have pulled my most glamorous and insightful friend’s face close to my own. I want to ask her for ideas of what to write you, so why am I telling a story about my father who, several months ago, forwarded me my car registration in the mail? And then later that very night, I woke up to the sticker shredded on the floor, and I was shoving tiny Sephora Rewards sampler lotions and toners in my mouth? Sorry, what were we talking about?

* * *

A little mystery is good.

* * *

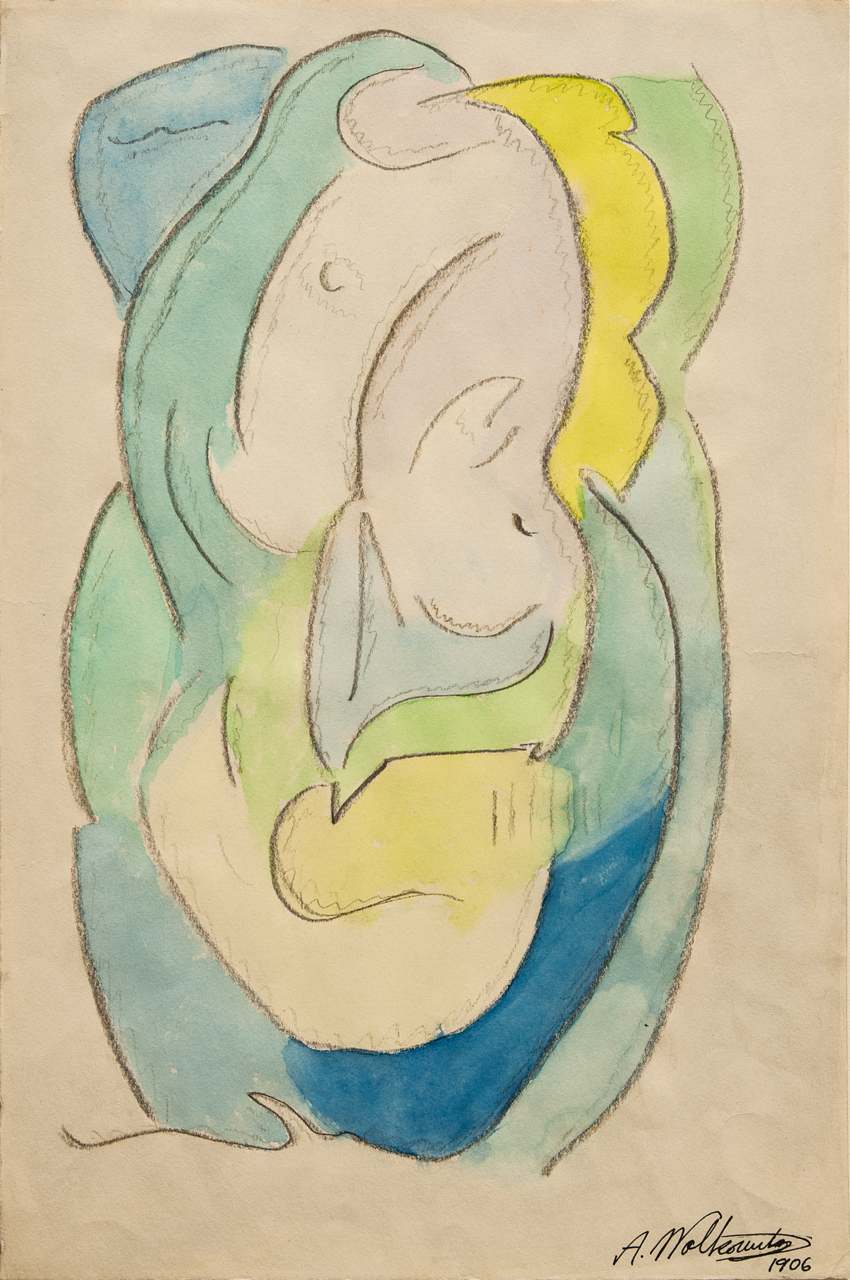

Image by Abraham Walkowitz via Smithsonian

Anna Kreienberg is a student who lives and works in Pittsburgh, PA. She can be reached at a.kreienberg@gmail.com