Juan Luis was desperate. He ran to his mother’s altar and dropped to his knees. A life-size statue of Our Lady of Mercy draped in a shawl of white gold held out her arms to receive him. He removed his cap and cowered in his lap. Outside, the rooster sang praises to the sun as the dawn mist faded on his father’s farm; swords of light pierced through the window and refracted a yellow hue on his back.

“Please, please, please send Pablo back to me.”

Tears fell to the floor.

“I’m not at peace; I can’t sleep, can’t eat. This love I feel for him… I’ve never felt for anyone. I want to give him a piece of my soul a-and spend my life forever with him. Please send Pablo back to me!”

Under the veil where you cannot see, a prayer materialized on the Lady’s open palm and fell like a chinola from its tree. Dust-sized and glowing dimly, the prayer rolled back and forth. They had been preparing for their first mission to serve a greater good, but the prayer now lacked the will to move. They only knew that they had to find a “Pablo.” What made them so important?

An elder spirit mounted Juan Luis to speak through him. An aura like the Lady raised above his body. His arms twisted and knocked over one of the glasses. Water doused the prayer, pushing them towards the doorway. The elder instructed the prayer:

Go to where the source of life smooths rocks,

Where love springs from dry ground,

Where you will find Pablo.

Pablo and Juan Luis’ love has been ordained holy,

But human ignorance threatens them apart.

Do not verge off.

Do not take any detours.

Do not attempt to help anything else.

For you are their only hope.

The prayer gained more confidence, a new light. They stood upright and recalled needing large vessels to travel long distances. At that moment, the farm dog stepped into the altar room, curious to learn who was speaking so strange. The prayer climbed on his paw, and when the dog used it to scratch his head, they clung behind his ear like a flea.

The elder spirit returned under the veil, and Juan Luis remembered who he was. He heard a ringing in his ear and turned his head to the dog. For a moment, it was like he could see the prayer. The dog couldn’t handle his intense look and skirted into the kitchen. Juan Luis turned back to the Lady’s open arms.

* * *

Smelling the scent of stewed hen, the dog encountered Juan Luis’s mother, who snatched the broom and smacked it on the floor. Her “No, you dirty son of a bitch!” hurt the dog’s feelings. He rushed out the front door and head-butted into a rooster, his black-blue comb wobbling. The dog yelped while the rooster got ready to fight. The prayer saw another opportunity and leaped to the rooster’s wing. The rush of oxygen from the impact reminded the dog of his lover, the other male dog across the road. He ran to be with him to love on him unashamedly.

The rooster didn’t know what to do with himself. He sang his morning song to celebrate that the sun had returned. What was he to do now? He scratched the red dirt, and his second purpose came to mind: fuck as much as he could in a single day.

The prayer, cocooned inside the rooster, gained more mass. They liked feeling heavy. Back home, they were massless, but Juan Luis’s words became their flesh. Here, they weren’t just one of many. They don’t have to submit to the collective will or consider the greater good; they could be selfish. They had heard so much about this world’s strange creatures with too much knowledge. Humans were known to enslave, eat, and bury alive their own kind, yet they were still worthy of our mercy?

Then they remembered what their elders had chanted to their students: Everything here dissolves into chaos. If you are lost there, then you can never return. No, they had a mission and didn’t want to spend one more minute here than necessary.

While the prayer contemplated their free will, the rooster made his way to the hen house, and the girls weren’t having it. He clucked around them, waving his comb and puffing up his chest, but they ignored him. He called out their names; they side-eyed him and chuckled at his clownery.

Tired of the rooster’s games, the prayer needed a new vessel. They peeked out of the wings and looked at the environment: bored hens, a tree with too many mangoes, cows napping under the shade of that tree, hills and more hills, and beyond that, more hills—nothing was moving anytime soon. They sulked inside the wing’s darkness; would they remain in this realm forever?

A bell rang. Confused, the prayer saw a yellow cow pushing against the wired fence.

“That farmer’s always too damn drunk to take care of us,” she yelled, “and his kids sit on their asses! I don’t get any fresh water! Fuck this shit; I’m going to the river!”

The river—where love springs from dry ground! She was their opportunity! They fled from the rooster at the right moment because he, not caring that the hens weren’t interested, forced himself on the slowest one to run.

Hopping to the cow was challenging: patches of morirvivis littered the ground, and its green leaves shut at the prayer’s presence. Morirvivis were said to fear being uprooted.

The prayer bounced from stalk to stalk to avoid danger. Cut by the wire, the cow wailed, and caught off guard, the prayer slammed into the plant’s softness. They struggled to free themself. The leaves smothered them, tiring them out. They could imagine spending the rest of their existence there when they laid down on its soft fibers. The plant, sure of its safety, opened again. The prayer saw the cow halfway through the fence, her body scraping against the now bloody wires. Bouncing on the red-orange dirt, they hooked themselves onto her tail, the last part of her body to escape.

* * *

Juan Luis’s father woke up hungover that afternoon and went to the window to see his property: his wife scrubbing the patio floor, his rooster harassing the hens, his cows getting fatter. He noticed a lack of color among the cows and was pissed to find his yellow cow had escaped. A buyer who wanted to breed her and sell her offspring planned to pick her up later that day.

The farmer cussed out his wife for her negligence. She came up to him and shifted the guilt to him. “Don’t disrespect me, stupid. You know I don’t give two shits about those cows. They shit everywhere! You told the boys to watch her—remember, asshole? And you smell like shit. Go wash your ass, and I’ll get your food.”

The farmer wanted to smack her smart mouth but needed to leave. He grumbled to himself and washed his face, armpits, and ass crack.

He called his sons to the kitchen. Most of his children—all boys, no girls—left the farm to work in the city because that’s where the money flowed. They were dead to the farmer. His family came from a long line of men who farmed back when their ancestors were forced to work on someone else’s land. Now they own their own land; how could they leave behind their overdue reparations? Those who remained were his youngest: twenty-something Juan Luis and his pre-teen twins.

He spat curses at their faces while he ate stewed hen with mashed auyama. Juan Luis, hoping to appease him, said, “I was praying at Mami’s shrine, Pa. And I sent the twins to buy some casabe.”

The farmer narrowed his eyes and grabbed Juan Luis’s ear. Twisting it clockwise, he said God was not going to rain money. If he wanted to pray, the farmer suggested he chop off his dick and join a monastery. The twins stayed quiet to avoid their father’s wrath.

When his anger plateaued, he announced that they were catching that cow. Juan Luis heard something ringing in his ear again. The twins started up their shared motorbikes; the farmer got on Juan Luis’s bike, rubbing Juan Luis’s head like he’d done when he was a baby.

They all rode through the gate; his wife, hands on her lower back, asked God, “When will this life get easier?”

* * *

Licking the snot from her nose, the cow trotted down the road. The prayer moved up to her head for a better view than her ass; they rested near her ear and processed all the emotions they had experienced: greed, anger, desire, despair. This was what humans experience daily? Back home, everything could behave as one being, one consciousness. But here, humans cause problems for themselves and scatter.

The cow slowed to eat a patch of tall weeds. She closed her eyes and chewed on its fresh bitterness. It tasted like the first time she could eat all by herself without the milk of her mama, who was sold to another farmer and never seen again. A cruelty the cow never forgave, she held onto her pain and turned her rage into hating her master, his family, and all humans.

As she moved forward, she bumped into a charred body hidden in the grass. Its head, hands, and genitals were cut off. The parts that weren’t burned to a crisp were black-blue bruised.

“A-ha!” she laughed, seeing the truth that humans could be ruthless with each other. The prayer, on the other hand, was sympathetic. They knew that a desecrated person’s soul could never sleep in peace. These kinds of souls stuck between the veil and here would complain about every pain they could remember. No one listens to them. How could they transition when their histories were erased? Maybe living in this realm was not easy.

The cow ate around the body until it was visible. She wanted other humans to see they could be slaughtered.

The cow marched forward while the prayer retreated into their fears. They had no clue what they were going to do. From their vantage point, they still saw fields and, beyond that, more fields. Where would they even find Pablo? He could be anywhere at any time. Why would the elders put them in a difficult situation like this? One part of them remained steadfast, but the prayer was scared.

* * *

Looking down at the river out of the window, Pablo considered jumping out and smashing his skull—his organs and blood splattered on the stone. No more love, no more passion, no more heartbreak. It was easier to imagine that than his present. It was a dissociation skill he learned from his mother, who learned from her mother, who learned from her mother, who saw her parents shot in the head by an American soldier.

When Death visited and took his father, Pablo’s mother was no longer anchored in this realm. Unless she was working at the lottery post, she watched TV all day: telenovelas, poorly-dubbed Turkish movies, debates justifying a bigger border wall, anything that moved with saturated colors. When the electricity went out, she would light candles and read Psalms like her matriarchs had done.

Pablo was an only child, so he had to manage the house. Do the cleaning, cooking, and shopping. During his downtime, he would absently gaze at the river, waiting for a prince to save him, or the wood grain beneath him, conjuring shapes that told him stories of old hurt.

Five nights ago, Juan Luis visited Pablo’s home for the first time.

“What kind of person wouldn’t meet their friend’s mother?” Pablo’s mother, suspicious of where her son was going at night, needed to see Juan Luis; she was insistent. It was a rare moment of clarity that annoyed Pablo. As long as she had her TV and Bible, why would she care if he was gone for an hour or the whole night?

Juan Luis rode his bike across the bridge and parked the motorbike in Pablo’s home. He heard the river’s soothing sounds. It helped him feel a little more confident. Pablo came out and kissed him on the cheek.

After the necessary greetings, she sat them down on the couch. Out of respect, they left enough room for the Holy Spirit; Juan Luis tucked his cap between his knees. The electricity had gone out on time; lit candles cast tender shadows.

She asked, “I always see you picking up my Pablo almost every night. Where do you two go?”

Pablo’s embarrassment heated his chest. Was she aware of what he was doing this whole time? They had been on the “down low” for over two years, understanding the unspoken rule that anything queer provokes violent reactions.

Juan Luis responded, “No, señora, we are just friends. We go to drink beers and have a good time, that’s all.”

“A good time, my ass. Pablo doesn’t come back home till the rooster crows—I counted three times last week. What kind of friends you two are?” The shadow deepened the wrinkles surrounding her eyes.

Pablo’s rebelliousness empowered him, saying fuck it to the pressure to be silent and said, “Yes, we’re more–”

Juan Luis turned to face Pablo and shot him a you-fucking-serious-right-now look.

“No, of course not, we are friends, señora—that’s it,” Juan Luis corrected; he was not ready for this conversation. How could he be when he didn’t tell his parents?

Pablo’s mother sighed. “Listen, I know my son… more woman than man. I see no problem, but people can take advantage of that kind of softness.”

“We only spend an hour or so together. I don’t know who else he goes to see,” Juan Luis half chuckled. Pablo’s heart flinched.

“You calling my son dirty?”

“No, no, no—but I-I don’t know what he does when I go home.”

The Holy Spirit between them turned tense. Pablo lost touch with this reality for a moment; he instead focused on the flickering candlelight that wanted to go out.

“You two can go do—whatever you planned.”

They stood up and walked out of the house. Pablo didn’t want to be near Juan Luis, and Juan Luis’s pride kept him from explaining his fear. Their love was brought to the burning light.

Juan Luis revved his bike’s engine and left Pablo behind. Powerless to the deep-rooted shame that loomed like an eternity, Pablo decided it would be better to leave him alone and turned his back. The exhaust’s smoke shrouded Juan Luis until he was just red lights on the road.

* * *

Seeing an unaccompanied yellow cow walk alone did turn some heads—more than a rotting body. The exploited farm hands with bundles of batatas on their backs were too tired to capture her. Besides, everyone in the town knew that taking another man’s property led to gunfire. They would be the ones who later told the farmer and his sons where they had seen her and in which direction she was headed.

At a crossroads three miles from the river, an overseer, a good friend of the farmer, reined in his white horse to block the cow’s path. He pulled out a lasso and threw and tightened it around her neck.

The prayer heard her gasping air and shrieking, “Let me go! Let me go!”

She twisted her head and stomped her hooves. Orange dust flew everywhere. The overseer used all his strength to restrain her irrational movements. Why wouldn’t she obey the noose around her neck?

Her cries became desperate. “I can’t go back, I can’t go back, I don’t want to disappear, I don’t want to disappear! Help me, please, help me!”

The overseer laughed, feeling primal power rising in his chest as he watched her suffer. The prayer was paralyzed, powerless against this senseless cruelty. What could they do? If she was dragged back to the farm, they would be back where their journey started. Time wasted. They pleaded for a miracle—please let God be true quickly!

An ashy-faced owl swooped in. She clawed on the arm that held the lasso. The horse, shocked to see an owl during the day, stood on its hind legs. The overseer fell on his back! The owl flew to the fallen man and tormented him, her talons cutting deep into his skin. He had no choice but to run away, and his horse ran after him.

The owl flew to the nearest post to be eye-to-eye. “My sister, are you ok?”

“No, I’m not,” her tone quivered, “I can’t be at peace nowhere.” The noose lingered like a bruise.

“Nowhere I can be at peace. Maybe leaving my farmer was a mistake.”

The owl squinted at her. “You came from a farm?”

“Yeah, I was thirsty for fresh water—for something to nourish me. My spirit’s weak, and I thought the water from the river can heal me, you know what I mean?”

She flapped her wings. “That will not happen, you know that? Your owner will be coming for you, and you will be put in the same place where you were. I see it all the time. I only helped you because your screams woke me. I am actually upset to be here in the first place—over some farm cow.”

“I didn’t ask you for your help. Get the fuck out!”

“Don’t bite the claw that fed you, stupid cow. Be grateful that I got rid of that human. Go back before you are dragged back.”

“You don’t know shit about me or what I’ve been through, so don’t tell me what I should do!”

The owl turned her back and flew away, leaving the cow to spiral: “Owls are supposed to be wise, and us cows mindless, right? What do I know? Do I know what I want? Why am I here—all these terrible decisions I made—what’ll they do to me? Shit, shit, shit, I’m fucked.” She couldn’t move nor cry—her heart beating slower. The prayer trembled as they felt a darkness overtaking her. Crap, they didn’t plan on caring about this cow; she was just a vessel to get to the river. In this situation, the elders would advise them to find another vessel.

No, the prayer couldn’t do that; they understood the gravity of her pain: she had been mistreated, objectified, and attacked. Her life was not hers. Compassion sprouted inside the prayer and bore love. Forget about the mission! Their priority was to convince her to keep going to the river.

Moving inside her ear, they sat inside and hummed a soft chant they had learned long ago. The cow heard a ringing that wouldn’t stop—a ringing that reverberated through her body, reaching her heart. In her mind, she heard:

Praise our mother of good that cools heads

Your water fills us

You who give babies to barren mothers

Praise our mother

You who gushes love from dry earth

Please help us flow like you

A hidden memory rushed to the front of the cow’s mind: When she was a calf, she, her mother, and the other cows were being herded through the mountains and had to cross the nearby river. The herd complained about getting wet, but her mother loved it. It was the first time the cow saw her mother laugh, her black and brown cowhide radiating. She splashed and played until the farmer whipped her. Her mother’s light was strong at the river.

The cow, excited to immerse herself in the water, lowered her head, stepped on the rope to free herself, and walked on.

The farmer and his sons caught up with the defeated overseer. He told them they weren’t far from catching her and explained how he was attacked. The farmer pissed himself laughing. Imagine it—a strong man defeated by a cranky owl. The overseer looked unaffected but made a silent epiphany that he clung to for the rest of his life and would pass down to his children and their children: God doesn’t like ugly.

* * *

Lifting his legs over the window’s ledge, Pablo heard his neighbors drinking their extra-large beers and barbecuing freshly killed beef. Speakers from another century blasted songs about lovers’ strife. He saw their kids run up the rocky hill to the colmado and come back with more beers and ice.

Pablo didn’t like them—plain and simple—but for a good reason. Never once did they pick up after themselves, leaving all their trash on the bank. They technically weren’t breaking any laws since the police spent their energy on protecting the rich landowners and harassing migrant workers from Haiti rather than caring about a little river.

He had confronted them two weeks ago, coming up in jean shorts and a cropped Tweety Bird t-shirt. That day, there were three couples; each girlfriend sat on their boyfriend’s lap; one of the girls had the biggest, gnarliest mole above her upper lip.

“Hey, pick up your trash,” he screamed over the speakers.

They laughed at his face. The girl with the hairy mole giggled, “What’s this lil birdie saying?”

“I said, pick up your trash! The trash you leave here hurts the river. We wash our clothes here. We bathe here. We depend on it! You treat it like it’s nothing!”

“Jaja! Clean it yourself; we know you’re a good housemaid.”

The girl threw a glass bottle in his direction. He flinched to avoid its shattering trajectory. Pablo had decided that it would be better to leave them alone than confront them.

Before deciding to take the plunge down, a familiar yellow cow walked over the bridge; Pablo couldn’t believe it—that meant Juan Luis must be close by! They could talk and hold each other again. He scrambled to change his clothes into something sexy.

The men outside of the colmado made kissy noises at the cow, demanding her to give them her milk. She whipped her tail at them as she went down the hill. The cow felt the river’s presence like she did as a calf. The couples, surprised to see this party crasher, sucked their teeth to get her attention. Their kids were more excited to see her and ran to stroke her. But the cow wasn’t stopping for anybody. The malicious kids threw rocks. The prayer understood a fundamental truth of this realm: when you stood out, humans othered you.

A boy grabbed the end of her tail. She kicked him right in the chest, shattering his ribs, puncturing his lungs, collapsing his breath. The other kids yelled for the boy’s mother, the girl with the hairy mole; when she approached him, her concern came out as curses: “God fucking damn it, this boy gone kill himself! You had be a fucking dumbass. I can’t, just—”

A small crowd appeared on the bridge, and seemingly-concerned people shook their heads. The boy’s father, almost thirty years older than his wife, pushed through the crowd to get his pickup truck. When he backed near the top of the hill, the men from the party picked up the boy and placed him gently on the truck’s bed. He was coughing blood. His mother was still on the bank, crouched, crying, panicking. The honk of the truck startled her, but she knew it was time to go and ran to the passenger seat.

Disregarding the chaos, the cow sloshed into the water; its coolness calmed her nerves; its pebbles massaged her hooves; its silky mud healed her ankles. Far enough in, she bent down—her hind legs first and then her front—to sit down, be still, let the current curve over her. She submerged her mouth and drank the water; it tasted fresh. Eyes closed and ears tingling, she listened to the river whispering; the voice was clear.

Shhhwoooshhhhhhhh, the river said.

The cow heard, My child, I am here—you are safe.

The prayer had leaped off the cow after she kicked that boy and climbed on top of a nearby boulder. The cow did not rejoice like they assumed, but she radiated peace. Exhausted and not knowing where to go to complete the mission, they slowed down and entered a meditative space. Would the elders punish them for not following their orders and banish them here? Who cares—getting the cow here mattered more. They rested and trusted that God would show them a way to return home.

* * *

At the height of the panic, Juan Luis, leading his family, arrived on the other side of the bridge. He beeped his horn, but the crowd wasn’t moving. He parked his bike, and his brothers did the same. The farmer yelled what the hell was going on, and an older woman who heard replied, “A poor woman got her heart stomped on by a horse!”

“Ma, what?” her middle-aged daughter turned to the farmer, “A boy got kicked in the chest by that yellow cow. Ma, who told you that lie? I swear, you look so stupid talking shit!”

The farmer didn’t have the time to entertain their bickering and plunged into the crowd. The twins followed, but Juan Luis detoured. Pablo had to be nearby. They had to talk; he missed holding the person he cared for most in this world.

Pablo, dressed in a golden tank top and green capris, felt Juan Luis’s energy and rushed to find him. He was no longer in control of his body; a ringing in his ear filled his heart.

Just as the truck carrying the injured boy and weeping mother got on the road, it almost swerved into the farmer. Releasing the pent-up anger about his life, his shitty job, and the futility of leaving behind generations of poverty, he kicked the door on the driver’s side and left a huge dent. He messed with the wrong person that day. The father put the emergency brakes on and leaped out, leaving the truck perched on top of the hill. He grabbed the farmer’s neck and slammed him to the ground.

“Get back in the car!” the mother cried.

The twins rushed to save their father and sneaked in a few punches at him, then men from the party came to support their friend, then men who believed the farmer was an innocent bystander came to help him. The men who wanted to break up this brawl came too, and then their women ran to pull their loved ones before they broke their necks.

The mother screamed, “This’s fucking ridiculous—put your pride away! Stop this nonsense!”

The crowd swarmed with more people and intensity, hard to tell what was a cry or cheer. Pablo, smushed between a bickering mother and daughter, wanted to give up and shut down. Was it delusional to think Juan Luis would be here?

Juan Luis jumped over a bleeding man and landed on a fire ant hill. The queen ant alerted her soldiers that they were under attack. The fire ant squadron swarmed Juan Luis’s ankle. He yelled in pain; Pablo recognized that scream. He listened, his pulse slowing. His yells reverberated into Pablo’s eardrums. He turned to the right, where Juan Luis struggled to release himself. Pablo charged towards him. Juan Luis grabbed Pablo’s hand; gripping Pablo’s knuckles, Juan Luis flew into Pablo’s arm. Like a star exploding, the impact blasted a passion so great that the prayer heard the lingering ring it created.

They looked at each other and couldn’t speak. Apologies and bitterness filled their throats, but love beamed through their hearts. They sneaked behind the colmado to reconcile privately.

The boy’s mother was not going to let her son die. She got into the driver’s seat, clutching the stick, and tried to put it into drive. It stopped in neutral.

“This shit won’t let me go!” She shook the stick while the truck shook with the men outside fighting. The dashboard blinked that the emergency brakes were set. She reached under, stretched her left leg, and released it. Right before she could grab the stick, the boy’s father was pushed hard against the rear bumper; the truck rolled down the hill too fast to comprehend.

Everyone stopped.

They all ran down, falling over each other like stones in an earthquake. Struggling to balance herself, the mother was too stunned to act; a memory of when her mother had lost control of the car and almost plummeted down a steep hill hit her body. Like she did that day, she jumped out. The boulders caught her, but the bones in her back snapped. Half of the crowd, led by the farmer, went to rescue the mother, and the other half, led by the father, followed the truck.

The truck rushed past the boulder the prayer was on and headed for the river. The water softened the crash and soaked the boy. The sudden cool water pushed Death’s hand away from the boy’s throat.

The splash alerted the cow that she wasn’t alone. She opened her eyes, and, for a moment, she and the farmer held each other’s gaze.

“I’m not going back,” she said to herself. She started to run until her hoovers couldn’t touch the sediment. The water caught her and shielded her body; she became a part of the river.

The farmer couldn’t help but cry, moving aside to let the other men help the mother.

The boy was still breathing, but his skin turned pale. The father got inside the truck and put it into drive. The men who had beaten the crap out of each other were now ramming their bodies against the truck to push it out of the river. The truck flew out and landed on the rocks, annoyed to sustain the enormous weight. The father stopped at the bottom of the hill so that they could place the mother in the truck beside her child. The hurt from abandoning her child, worse than her broken bones, calmed when she cradled his head and felt his breath as the truck dashed off.

* * *

Juan Luis, on his knees, felt the rapture he experienced at the shrine, but he choked on his words. Opening his heart tightened his throat. Also on his knees, Pablo held his lover’s hands and initiated the conversation: “I know we haven’t talked since that night… I’ve missed you.”

“I-I’ve missed you so much,” Juan Luis said, taking off his cap and casting his eyes on the red dirt. “I don’t like it when we’re fighting.”

“Me neither….” A breath before he asked: “Were you afraid of my mom knowing about us?”

Juan Luis’s gut clenched, and he squeezed Pablo’s hands. “You know you remember when I first said ‘I love you’ here?”

The memory hit their bodies before their minds could remember: On the holiday of Our Lady of Mercy and the anniversary of his father’s passing, Pablo had drunk too much white rum and decided that he needed to swim in the river. Juan Luis was against it since Pablo was bumbling, but Pablo got his way, batting his dark-brown eyes and long lashes that Juan Luis could get lost looking into. By the river bank, Pablo undressed down to his underwear, unleashing the gravity of his wide hips, and Juan Luis couldn’t help but feel a pull in his jeans.

“Take off your clothes and come in with me, baby,” Pablo slurred.

“Someone has to be dry just in case,” Juan Luis laughed.

Arms spread out for balance, Pablo walked into the water, and he looked behind and saw Juan Luis looking like an archangel. He reached in and splashed some water on his head and chest; the tingling on his nipples tickled him. He splashed more water on himself; the drops sparkled like jewels not of this world.

“Come closer, baby, the water’s cool, baby.”

“I’m fine where I’m at.”

“I guess I need to bring the water to you,” Pablo squealed before rushing to where Juan Luis stood, but before he could soak him, his feet stepped on a too-slippery rock, and he fell on his ass. Juan Luis laughed not because Pablo was in pain but because the first words Pablo screamed were, “Juan Luis, help me!”

He picked up Pablo in his arms, feeling the rush when their skins touched, and kissed his forehead. Pablo whimpered that he wanted to go home.

“Ok, baby, let me take you home.”

“No! Not to my mom! I want to go home with you—have you by my side.”

The bold assertion caused Juan Luis to stop moving. “No… not today—but we’ll have a home together, I promise, we will.”

Pablo sucked his teeth. “I get so lonely without you.”

“We will have a home together.”

“You don’t mean that; you lie, lie, l—”

“No, I will never lie to you—Pablo, I love you.”

Stunned to hear the words he longed to hear, Pablo remained quiet as Juan Luis helped him dress again; the river purred in the background.

“I told you the truth in my heart.”

Pablo almost cried, reliving the moment, and smiled. “Yes, I remember—you carried me back home after I busted my ass.”

The memory’s warmth evaporated their anxieties. “You know, I’ll always, always love you, Pablo, that’s never going to change, b-but—”

“And I will always love you… and we don’t need people to know our business, right?”

Between them, the question lingered: will their love always be hidden?

* * *

It was quiet after the truck left; everyone went back home to begin their nightly rituals. The townspeople laughed that something had possessed them. Wives and daughters cooked dinner while the men cleaned their wounds and gossiped about who was the weakest during the brawl.

Juan Luis and Pablo, holding hands, ran into the farmer, wailing by the bridge. The twins were ready to go home, annoyed that their father was crying like a baby. Juan Luis’s fear spiked in his heart like it had that awful night, but holding Pablo’s hand reminded him of what he had almost lost.

The prayer, deep in meditation, hummed the chant to the river they had done earlier as Juan Luis charged to them and pulled Pablo behind him.

“Pa, I know that it’s not a good time, but… this is Pablo, and, and—”

Juan took off his cap, inhaling to quiet the ringing in his head, “I’ve been leaving the farm to see him almost every night ’cause—”A squeeze from Pablo’s hand jolted Juan Luis to say what had been unspeakable. “—we’re together. I—I love him, Pa, and he loves me.”

“Nice to meet you, señor!” Pablo blurted.

The farmer’s tears stopped flowing like he had been slapped. Worried about how he would afford to maintain his farm, he couldn’t process the fact that his son was a faggot. That day, he lost another son to that city lifestyle. His blank expression concealed how repulsed he was. He nodded indifferently at Pablo and said it was about time for him and the twins to head home. The farmer and the twins squeezed onto one seat, leaving the other motorbike behind; the truth was that the farmer didn’t want to ride with Juan Luis, a stranger to him.

“Well—that went like I feared it would….” Juan Luis placed his cap back on, his voice cracking.

“Listen, I’m here by your side—you’re not alone, ok?”

Juan Luis smiled and kissed Pablo’s forehead.

On a weary high after the hot-air shame had released its pressure, they stayed at the bank to talk about a new future they could build together—imagined collecting moonlight, dew drops, fluffy clouds, and smooth crystals to make the home where they could be at peace.

Rested, the prayer became aware of their surroundings. They climbed down the boulder and caught Juan Luis holding onto someone. Walking towards them, they heard him say,

“Christ, Pablo, if you think about it, if that cow didn’t come here—”

It was Pablo! The elders were wrong; the detour, the divergence, helping the cow was God’s way! Then they noticed that the cow was gone; the spot she sat now shrouded in a shadow. They hoped she was at peace.

The couple stayed out until the stars blossomed in the sky.

Lying on Juan Luis’ chest, Pablo asked, “Can you take me back to my mom’s?”

“As long as I can come in.”

Pablo blushed. “Yeah, that shouldn’t be a problem.”

Their mission now completed, the prayer decided to remain at the river, the only place that reminded them of how their home under the veil felt.

Juan Luis turned on the bike, and Pablo held on to his waist tight. The waning moon lighted their way. Passing them on the road was the truck from earlier, with Death following right behind.

Juan Luis slowed down when something large approached them. He turned on the headlights and saw the cow, drenched in water but alive. She was shocked to see the farmer’s son, but he was smiling. He didn’t try to capture or stop her. She hurried into the bush.

“If she wants to be free so bad, then she better survive,” Juan Luis laughed.

In front of Pablo’s house, Juan Luis turned off the engine and sighed. They could see the TV’s blue light and his mother’s flickering shadow.

“Come inside,” Pablo said, nudging into Juan Luis’s neck, “We can talk with her again. Remember, I’m here by your side, ok?” He kissed Juan Luis, who thanked God for answering his prayer. Later that night, cracking up at Juan Luis’s jokes about the huge brawl, Pablo’s mother felt like she gained another son.

* * *

Back at the river, the veil lifted, and the prayer could see the golden darkness where they came from. They hesitated to go; once they go through, it could be decades or centuries before they are called to come back. The bridge would be destroyed. This town would be gone. The people they saw would be dead. Everything man-made will be changed. But this river would still be here; maybe she would remember what happened today.

The prayer returned where you cannot see.

* * *

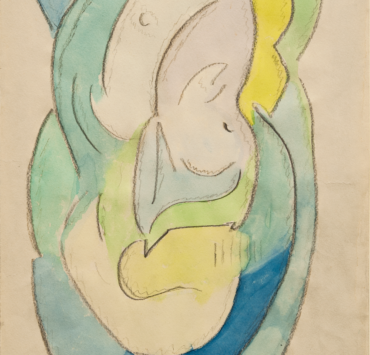

Image by Emmanuel Abreu

Leo D. Martinez is an Afro-Dominican American artist from Harlem, NY, who resides in Atlanta, GA. A Periplus fellow, she has published her fiction in Plantin Magazine and ¡Pájaros, lesbianas y queers, a volar! Anthology and her non-fiction in Electric Literature; she was also an honorable mention for the 2021 BCLF Elizabeth Nunez Award for Caribbean-American Writers. You can find her napping on a rock by a river, walking her dog, or on Instagram & Twitter @leyetheecreator.