In August of 2021, I visited my place of birth, the Dominican Republic. A couple of weeks into my stay, an earthquake affected Haiti. Terrible in scale, it would come to be considered the deadliest natural disaster of 2021. It killed approximately 2,200 people, injured six times as many, and displaced hundreds of thousands. Next door in my country, people were largely unaffected by this earthquake but had been rattled by an extensive and aggressive number of tropical storms. Many murmured about how unlucky Haitians were, measuring misfortune on a scale of current and past disasters. Dios los salve, pero que mala suerte, I heard, over and over again. People spoke of the mercy of this earthquake. It hadn’t been as brutal as the earthquake of 2010, which killed over a quarter of a million people.

The day of this most recent earthquake, one of my mother’s neighbors leaned over her front porch, whispering, you have to wonder what those people might have done in a past life to deserve this kind of fortune. I was traveling with my two young children, seven and eight years old at the time, and they slept with me that night, while the neighbor’s words, shocking in their cruelty, echoed in my head with that persistent Christian timbre of judgement – whatever bad shit happens to you in this life, must be your fault, somehow. I didn’t share her sense of moral superiority. I worried about aftershocks. I envisioned escape plans in the event disaster touched us. I had bottles of water nearby. The next morning, the sounds of a bird flapping her wings right outside of my window startled me awake. It was surreal, the sound of feather against flesh, pulling me out of a dream where my own body had been paralyzed beneath rubble, yelling out for someone to come help, my children beyond my reach. I shivered. I got up. I went about my day, fed my kids, snapped back into vacation mode. Haiti and those affected slipped from my mind and I was grateful to not have to face the horrible possibilities of a natural disaster.

The central concern of Chancy’s novel is elegant and complicated – fragmented stories show human beings before and after the tragedy but it is the fragmentation itself that acts as a light to reveal meaning in the chasm, much in the way a puzzle can only be solved by understanding the shape of the pieces and how they fit together.

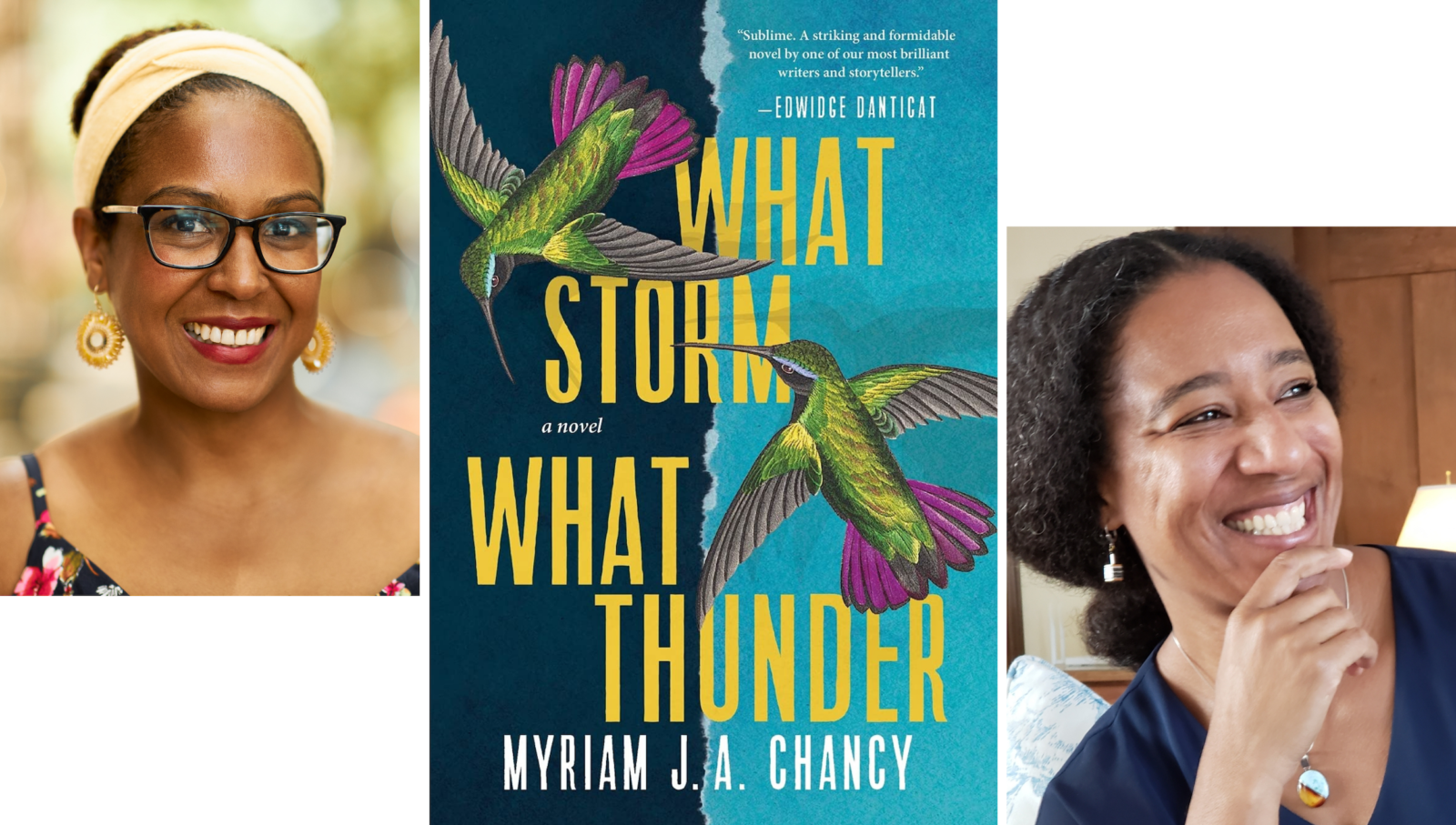

A month later, I fell into the wonder of Myriam J. A. Chancy’s latest novel, What Storm, What Thunder, which tells the story of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and its aftermath through interconnected stories. This beautiful and breathtaking work of fiction manages to stay rooted in the horrors of the day but also branches out to show us a nuanced view of the Haitian diaspora. The central concern of Chancy’s novel is elegant and complicated – fragmented stories show human beings before and after the tragedy but it is the fragmentation itself that acts as a light to reveal meaning in the chasm, much in the way a puzzle can only be solved by understanding the shape of the pieces and how they fit together.

Take the characters charged with illuminating this human condition. Ma Lou, a market woman, opens and closes the novel. She is a character that grounds the book and many of the characters within it. She has the wisdom, the unsentimental precision of vision, and the nurturing soul that anchors the neighborhood both before, during, and after the tragedy. This wisdom has been hard-won through abandonment and loss. Her son, Richard, is an extremely wealthy man who turned his back on his mother and his daughter, Anne, in pursuit of upward mobility. His near-perfect life – for he can’t escape the kickback of being a Black man functioning in a white man’s world – of privilege is fractured when his wealthy white wife discovers the existence of his secret child, who is now a fully grown woman. Richard is beckoned to Haiti by his daughter, who also returns to Haiti days before the earthquake to bury her mother who has died of cancer. Richard, instead of seeking to give solace to his estranged child, comes back home to score a huge financial deal by selling a natural resource – water, no less – to his own people. When the earthquake strikes the country, Richard’s daughter has already left, and the poetry of the moment reverberates deeply. He has lived a shallow and empty life, where the capitalist accumulation of wealth and status has been the main driver of meaning and purpose. When we come to find that even his body disappeared, we understand the legacy he leaves behind is not material possessions but his children. Anne, whose education he financed while refusing to have a relationship with her or even acknowledging her existence, returns after the earthquake as an architect, poised to rebuild much of what has been destroyed.

Whether we’re impacted directly, by having loved ones touched by these great disasters, or not, every single one of us is seared by each incident – if only by the sobering realization that it can and will likely happen to each of us in due time.

Chancy masterfully discloses the human cost of a disaster of this magnitude can only be understood through that which can never be reconstructed. There is Sara whose immediate loss of her two daughters leaves her numb and dazed, only to be further compounded by her husband Olivier’s abrupt flight. He pretends he’s merely heading to another camp for work, to gain the stability necessary to rebuild their life but we know, just as Sara knows, it is the pain of loss he’s unable to cope with. Their young son, Jonas, dies shortly after his father flees, hurling Sara into madness. It is in the madness of Sara’s loss that so much of what the characters are confronted with comes into sharp relief. It is no secret that natural disasters affect those most vulnerable in the worst possible ways. And so we witness young Taffia, a teenager who is most concerned with friends and parties before the earthquake, fall victim to a band of criminals that begin to terrorize and rape the people in the camps. Paul, Taffia’s brother, chooses to join one of these bands of men hellbent on creating further chaos and despair – if there is a choice to be made between suffering and inflicting pain, Paul sees his choice as a no-brainer.

One of the most affecting portrayals of displacement is nestled in the story of Didier, a taxi driver and older brother to Taffia and Paul, who lives in Boston. During the moments after the earthquake, he finds himself unable to call home or have any word of the whereabouts of his family. An overwhelming sense of helplessness envelops Didier from which he emerges transformed. Didier’s experience is of a terrifying suspension: the possibility of having lost everyone he loves becomes certainty in his mind. We come to understand the event is a transformative force that spares no one. Didier emerges from this suspended state as someone who no longer believes in community, who sees the cycles of human suffering and the rising climate disasters as an endless hell we’re all living through. Whether we’re impacted directly, by having loved ones touched by these great disasters, or not, every single one of us is seared by each incident – if only by the sobering realization that it can and will likely happen to each of us in due time.

At the end of the novel, we find ourselves in a car with Ma Lou and many of the female characters whose stories we now carry within our bodies. Ma Lou reminds us, in prose so beautiful and lyrical it threatens to leave us mute with awe, that many of the human beings lost to the earthquake might have been spared death. There is no sentimentality in this acknowledgement. It is presented as fact. Perhaps even more striking is that many of those who have survived the earthquake are shells of their former selves, vacant in haunting ways. The scene that follows is a ritual of honor, of laying souls to rest, of allowing characters and readers alike the meditative stillness of sorrow. In a powerful maneuver of craft and emotional force, Chancy manages to show us the way ahead by lingering in the past and establishing this novel as a seminal artifact of the wisdom that will be required as greater and greater climate disasters continue to ravage our world.

What Storm, What Thunder by Myriam J. A. Chancy was published by Tin House Books on October 5, 2021, and is available wherever books are sold.

Cleyvis Natera is a novelist, short story writer, essayist, and critic. She is the author of the debut novel Neruda on the Park, which was a New York Times Editor’s Choice and was awarded a Silver Medal by the International Latino Book Awards for Best First Book of Fiction. The recipient of awards and fellowships from PEN America, the Vermont Studio Center, Hermitage Artist Retreat, and Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Natera studied literature and creative writing at Skidmore College and holds a M.F.A. in Fiction from New York University. Her fiction, essays and criticisms have appeared in Kirkus, The New York Times Book Review, URSA, TIME, Gagosian Quarterly, The Brooklyn Rail, The Rumpus, The Washington Post, Pleiades, The Kenyon Review, Aster(ix) and Kweli Journal, among others. Her second novel, The Grand Paloma Resort, is forthcoming August 2025 from Ballantine Books. Natera currently teaches creative writing at Barnard College of Columbia University and Montclair State University. At Montclair State University, Natera leads the development of a new Bilingual M.F.A. Creative Writing Program.