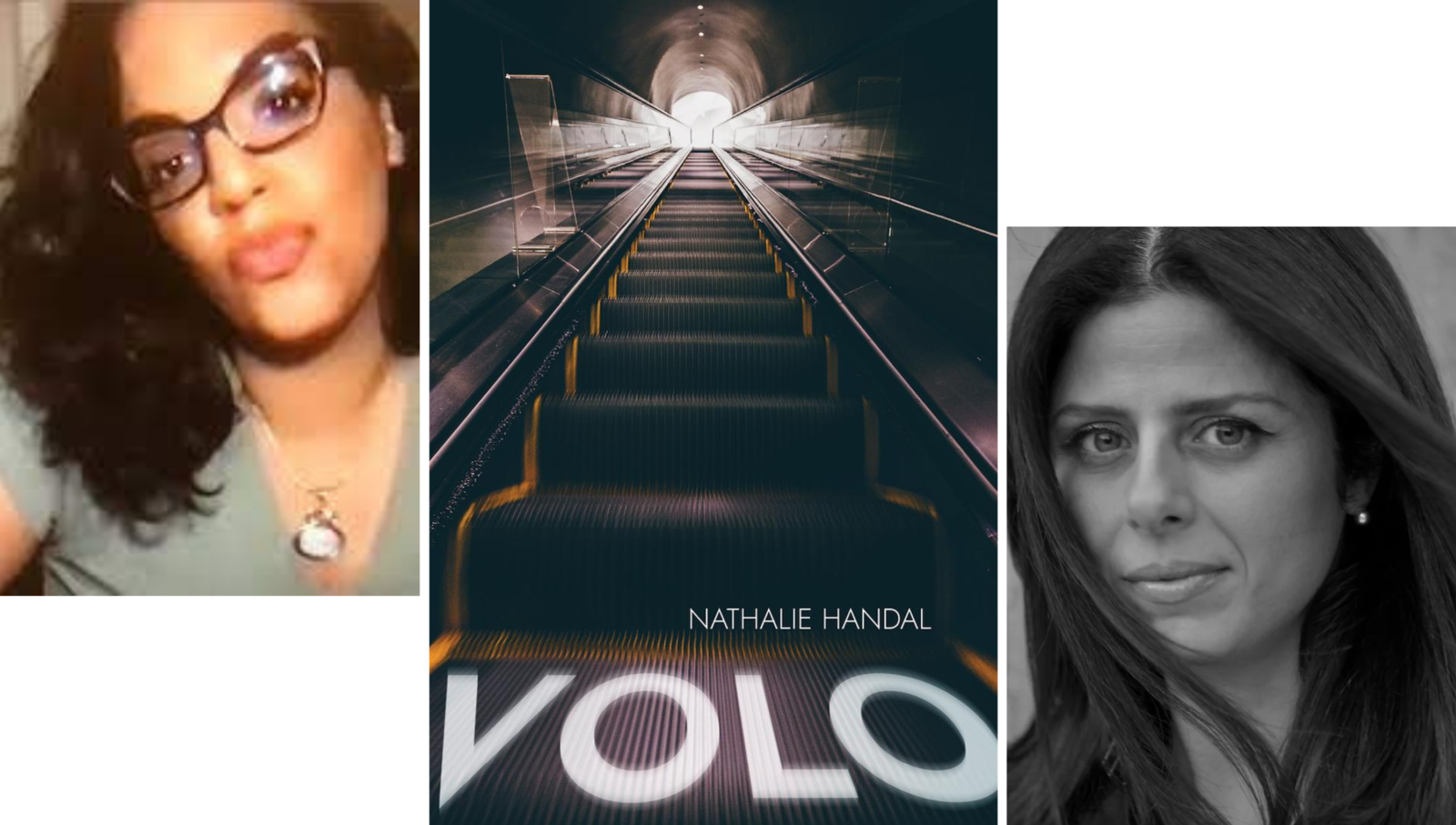

In the essay Site of Memory Toni Morrison wrote, “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” The emotional memory in Nathalie Handal’s Volo delves into “nerves and the skin” of the ruins of water, what it means to move through the world and stay in your body. Volo (from the Latin for “to fly, want, wish”) opens with a stunning and detailed drawing by Molly Crabapple: woman in sultry white dress, leaning against New York City fire escape, the cerulean Mediterranean underneath, late summer. Her face slightly tilted, nostalgic.

Volo’s lingua franca is a fusion of the sea and the city. Fragments and brevity are characteristic to Handal’s body of work. Her poetics explore movement, migrations, and desire. She mixes impermeable beats, heady questions, and conversations with the dead, she writes: “when lips are drying / will the rain keep her exhalations / like a necklace of water.” Handal collapses the borders between surrealism and realism, the cinematic and the ordinary. And the use of repetition amplifies her global influences. You can hear echoes of Leonard Cohen, Fairuz, Arturo Sandoval, and her intersecting identities: Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, French, Italian, Latin American and the Caribbean reverberating from her apartment in Queens or Rome.

The elegiac chapbook is composed of two long poems. The first poem “Téssera” is a quartet and loosely in conversation with American Modernist, Hilda Doolittle’s (H.D.) who wrote under the impact of World War II. The speaker navigates the routes of H.D.’s London, Egypt, and the steel towns of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Handal seduces us with the power of mysticism, love, women, death:

“Pompeii taught us nothing

but told us everything: That all can erupt

and kill us

but we will

survive

In the city’s

house, paintings, objects

But what did the women say

of the hundred hours of harm?”

Her approach to form centers the erotic: “I ask her if we are born/in two directions/I tell her/Lady Comrade/take me, like you did/when the war was over/and life was a short ghazal. The poems traverse centuries, where the speaker encounters Assante, Venus, Isis, Santa Sophia, Ophelia, Sappho, and other historical figures silenced by patriarchy who chose to reclaim the divine feminine: “They forget we are women / They keep on forgetting.”

The second long poem, “After Kaddish,” embodies the restlessness and wild heat of Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish and the roaming spirit of the poet Mahmoud Darwish. The poem was inspired by Handal’s first writing assignment, which was to interview Ginsberg for Darwish’s magazine Al Karmel. Ginsberg died a month or so after, in 1997. When Darwish died in August 2008, Handal began to write “After Kaddish,” as she mourned these two poets:

“Allen, when you died, I was with Darwish in Ramallah

We both said nothing

What could we say

the sun tangled in our shadows.”

The central question of the chapbook is not so much how do you measure grief but how can you possibly sustain it: “Whom have we betrayed? / Which wisdom, which age? / There was a city on the train/Did you see its color?/ Mystic blue/Then yellow.” The speaker confronts silence, longings, and the constant paradox many immigrants face in America. It never evades the difficult questions and insists on remembering: “I wonder if the old man speaks English now / wonder what he hides / I was twelve when / I hid the old map with shame written on it.”

In an interview with PEN, Handal notes: “Language is always calling me- showing me how to see freedom; how to arrive in the worlds in the words, phrases, sentences I’ve collected; moving stillness and symphony into synchronicity.”

Death shows up as a rooster, a red ribbon, or “a broken down bus on the way to Hebron.” The structure and imagistic quality of the poems allow the speaker to push against the language of dreams and the physicality of the natural world, she writes, “I replace heat with more heat/Replace ache with winter/ winter with a familiar voice/ voice with a wound I confuse with a patch of bitter plants.” Line breaks transmit energy creating a kind of interior cinema. Colors and weather reveal loss or aliveness—body heat.

It was powerful and exciting to find remnants of a not yet gentrified Journal Square and Kennedy Blvd which runs through Jersey City — a historical, transitory port for so many immigrants and artists in exile. It was the city Ginsberg touched before Manhattan which rarely (if ever) gets the deserved attention when speaking of American poetry movements synonymous with New York literati. “After Kaddish” is like being inside an abandoned medina — a sense of death and ruin is continually pinned underneath the abundance of light.

And despite the decay, we linger with every return: “It’s come back—my dream of New Jersey. It’s a strange place to be lonely in.”

To read Handal is to exhume life, pleasure, and the deep neon of history.

María Guzmán is a poet and writer. Her poems appear in EcoTheo Review, Rattle Magazine, and The Account: A Journal of Poetry, Prose, and Thought. She has been nominated for 2020 & 2021 Best of the Net. María has received support from Community of Writers at The Valley, Breadloaf Writers’ Conference, and VONA Voices. She received a BA in Urban Studies & Anthropology from Saint Peter’s University and MFA in Poetry from New York University.