You are a mouse. You have a comfortable home. A dense layer of wood chips undulates and crunches under your paws as you walk. You have shredded some to build up a soft, puffy resting place, where you sleep when tired. When hunger strikes, you can always find something to eat. There is plenty of clean water. Light alternates with dark in a constant, familiar cycle. Your charcoal gray coat shines with health.

Every day, you encounter dozens of well-known scents: the piercing ammonia of your own urine, the bright crispness of fresh wood chips underfoot, the close mustiness of the other mice you live with. All these fragrances layer and intertwine to form an olfactory white noise: the aromatic backdrop of your life. Nothing is amiss.

But one day, something new: your pink whiskered nose twitches as an altogether different smell wafts through the air. It is delicate, sweet. You stop walking to inhale deeply. But the sweet smell quickly dissipates, and before you get moving again, you feel it: a zap, there, in your paw.

That was weird. Kind of hurt, too.

You pad your way over to the water, and lap up some hydration as you wonder what happened. Your roommates look just as bemused as you feel. They must have felt it too. You eat a few pellets of food. You sniff the air rapidly, whiskers twitching. No sweet smells. Just white noise. Hmm. Maybe you imagined the whole thing.

But as soon as the thought passes, there it is again: a disembodied saccharine fragrance. This time you know what might be coming, and right on cue, you feel that painful zap on your paw. Before the day is out, the whole sequence of events happens three more times. The same thing happens again tomorrow. And then the next day. When all is said and done, you have learned something new: whatever that sweet aroma is, it brings the promise of a nasty shock.

Your brain encodes the lesson: We don’t like this smell. We must remember this.

My email inbox has a custom wallpaper. It is a grainy, old photograph I found in the attic of my maternal grandfather’s house. In it, a tall thin pyramid of sepia looms over a large colonnaded rectangular pavilion. An amorphous, massive statue rests within the pavilion, a circle of light glaring off its black curvature. The photo makes for an impractical background. Every time I open a message, the image is obscured. The grayscale washes out the entire screen. It would make sense to swap it out for something more aesthetically pleasing and practical, but I know I won’t do this.

I am attached to this photo, to the place it represents. I always have been, with a fervency that I never fully understood. If I ever got a tattoo, this image would be on the short list of possibilities. My most tattooed friend tells me this would be a poor choice: the tower’s intricate façade would make for an impossibly messy etching. I suppose she’s right. Still, I can’t seem to turn away from this image, from this place that enchants me so. The big temple. Periya Kovil. Rajarajeswaram.

***

You are a mouse again. Charcoal gray coat, pink nose: to humans, you look almost identical to your father. Your father’s life, too, was almost identical to yours. He ate the same food, drank the same water, walked the same wood chips, made a nest with the same materials. His fragrant world was the same mix of piercing ammonia and fresh clean wood and musty bodies. What you don’t know is that one day, before your conception, when your existence was barely an idea, your father sniffed something new.

It was pleasant at first, this new, insistently sweet scent. He stopped to take it in. But every time that fragrance came, it brought pain. So he learned that this scent was a harbinger of danger. This scent should be feared.

Of course, you don’t know all this. Your father has never told you these stories. And so you go about your life blissfully unaware. One day, your daily roaming is interrupted by a startlingly loud sound. You jump. You squeal indignantly. Your reaction isn’t surprising. Who doesn’t jump when they hear a loud noise?

What is surprising, though, is how high you jump when that loud noise comes after an unfamiliar smell. You’ve never encountered this fragrance, have no reason to dislike it, but you find it cloying, saccharine, sickeningly sweet. Unexpectedly, your fur stands on end as soon as it wafts through your nostrils. Another loud noise soon follows. You jump again, this time much higher than before. There is something eerie about this whole thing. You have never known this odor. Yet you can’t shake the feeling that this experience isn’t new. Somehow, you have felt this before, as if in another life.

I was born in a city called Thanjavur. In my mind, it is a quaint town, but in reality, its population is over 100,000. It is a microcosm of India, the ancient alongside the modern alongside the animals alongside the cultural and religious diversity. In the old city, where my relatives live, small open sewers run sluggishly on either side of narrow lanes. Carefully placed flat stones bridge a path to the homes, periodically obscuring the cloudy water and unmentionable offal flowing beneath. One plaza, where the dominant features are a modest temple and the massive ceremonial chariot parked just outside, is overrun by goats. They clamber over the chariot like children on a jungle gym, exercising their instinctual alpine agility in this city on the plains.

On all but one of my trips to India, I have spent time in Thanjavur, where my mother’s family settled in the late ‘70s. 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2014, 2018. Seven trips. Eight, really, since Amma and I managed another quick visit at the tail-end of our months-long family trip in ’96. We were staying in Chennai, in my paternal uncle’s home, when she tearfully confessed to me that she missed her own mother desperately and wanted to see her again. Eight years old and bestowed with the simple clarity of childhood, I said, So go see her. We booked a train and traveled southward and inland, to my mother’s mother’s home. We ate food made by her hand. We braided our hair by the light streaming through the open back door in her black-floored living room. We wore fresh jasmine garlands in our hair every morning and evening. We visited the temples in Thanjavur, including my very favorite, Rajarajeswaram. For a few extra days, I basked in a luxuriously matrilineal world.

On the train ride back to Chennai, my mother gathered me close, kissed the top of my head, and said “En rajathi” (my little queen). That stolen trip was the last time I saw my maternal grandmother, who died the next year in a freak accident. She was fifty-four years old.

Thanjavur is not technically our native place, as Indians like to say. The family can trace its roots to surrounding towns and villages: Thiruvaiyaar, Mellatur, Thiruppoonthuruthi. The further into history I reach, the more consonants fill my mouth. Nevertheless, Thanjavur is the only maternal hometown I know. That trip in ’96, it became my favorite place, the only city in India where I reliably felt connected to the country. Neighbors recognized my mother, and were delighted to meet her children. Our doting uncles lavished affection, buying us coconut water whenever we wanted and hunting for a palm fruit seller to satisfy my cravings.

In Chennai we sat in our relatives’ stuffy flats and waited for our cousins to get home from school, whiling away the hours rereading books and watching cartoons in languages we didn’t understand. In Thanjavur we seemed to go on adventures every day, walking to the aranmanai (palace), visiting the tailor’s shop, browsing for kaleidoscopic art plates and jewel-studded Thanjavur paintings at handicraft emporiums. The summer of ’96 had demonstrated that my sister and I, having moved away only four years prior, had become irrevocably American. But being in our mother’s hometown—which, technically, was also ours—suspended that fact for a time. Despite remembering nothing of this city where I was born, I felt there what I had naively hoped to feel throughout India: a sense of reunion, a thrill of recognition, a recollection of my previous life.

***

Become a mouse again. This time, you are the grandson of a rodent whose paw was zapped whenever a sweet odor drifted through his cage. You don’t know it, but your father was unduly startled by this very same fragrance. It made no sense—why would a mouse be spooked by something he had never experienced, something only his father had cause to fear? But spooked he was. It was as if his father’s experience was embedded inside of him. This, of course, flew against the commonly accepted science of inheritance, but your father’s leaps were undeniable. Somehow, that zap to your grandfather’s paw had traversed a generation.

One day, a sudden clattering noise reaches your ears. Startled, you jump. The sound disappears, and you relax. Soon, though, something you’ve never experienced: a sickly sweet aroma. Inexplicably, you are immediately on edge. The sound that follows makes you leap much higher than before, frightened of an ineffable something you can’t put your finger on.

Once your paws are back on solid ground, you start to think. That fragrance was foreign. You know this. But you also know this contradictory truth: You recognized it immediately. It’s as if a memory from another life lives inside you.

***

Rajarajeswaram is a temple complex commissioned by Rajaraja Chola, one of south India’s most famous emperors. Dedicated in 1010 A.D., it is an edificial historical register, checkered with art and architecture from empires of the last millennium. It was damaged by Mughal invasions, restored by Hindu emperors, commandeered by Europeans. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

I knew none of this as a child. My family has always employed its Tamil name, Periya Kovil (big temple). I formed my first conscious memories of Periya Kovil that summer of ’96, visiting with a three-generation retinue of maternal relatives.

We must have arrived by auto rickshaw, a sort of covered, motorized tricycle that seats three adults uncomfortably and navigates Indian traffic with stunning agility and an impossibly tight turning radius. [We call them autos, the “ah” stretched by a jutting mandible and the “to” swallowed up by the soft palate, destroying any trace of English.] On the dusty external courtyard, a platoon of cycle rickshaws waited hopefully for potential passengers. We crossed over a shallow grassy ravine, the only evidence of the moat that once flowed here, and ducked through a light pink entryway.

The first gopuram (gate) grew before us, a wide-based, sand-colored archway covered in sculptures. Divine entities abounded, some many-armed, some in the classical arramandi (bent-kneed) stance of Bharatanatyam dancers, some folded nimbly at the waist, arms resting casually on nearby carvings, others with one leg crossed over their bodies and held high with a bent knee, mimicking Nataraja, the god of dance. For five rows the gate rose, narrow metal-grilled windows marching along the center. I could have craned my neck to stare for hours, but I rushed behind my family.

In the next courtyard stood a decorated temple elephant. I scampered toward it with unabashed eight-year-old glee, probably squealing “oh my gosh” in my jarringly American voice. One by one, we held out coins, and the animal plucked them up, curled its trunk into a pachydermine fist, and lightly thumped our bowed heads in a blessing before depositing the coin into the mahout’s outstretched palm. To my utter delight, after a brief discussion (and, I realize now, an exchange of money), my father hoisted me onto the elephant’s back for a short ride. I must have been wearing the lemon-yellow romper my mother bought especially for the trip, because I remember surprisingly bristly hairs pricking at the bare flesh of my thighs.

Disappointingly plucked off my gray mount, I entered the second gopuram, where inscriptions in Grantham, an ancient form of Tamil, bloomed across the stones. I could read neither language: two layers of linguistic disinheritance. Eyeing those inscrutable words, I wondered if my parents could read them, my grandparents, their parents. How many generations had come to this place? Head filled with those who came before me, I emerged onto the vast main courtyard.

Compression. Release. Awe.

Fifty yards ahead rose the largest vimana, temple spire, I had ever seen. I stood transfixed by the sheer size, the riot of sculptures, the stately magnificence. In the foreground, a few steps led to an expansive brick-laid dais, elevating the main vimana and a columned pavilion that housed a massive black statue of a seated bull. As we filtered past the statue of Nandi, Shiva’s vehicle and servant, he gazed toward his master with bovine contentment.

We ascended a wide stone stairway into the temple, and a wash of familiar fragrances tickled my nose: sharply bright floral notes from the flowers in women’s hair. Earthy dust in the unlit corners. Sticky residue from hundreds of years’ worth of oil lamps. Metallic sharpness from the brass bells. Light sweetness from glistening, freshly cracked coconuts.

Past pillars and paintings hardly visible in the gloom, we proceeded to the sanctum, where a hulking black Shivalingam presided. The deity’s Sanskrit name is Brihadeeswar, a portmanteau of brihat, meaning vast, and eswar, denoting Shiva. His Tamil name is Peruvudaiyar, which translates to “great deity.” Still another name is Rajarajeswara, a nod to the emperor. As a child, I ignored these layered names, and saw only the familiar Lord Shiva. A sweaty priest climbed a metal ladder and waved a tiered oil-wicked candelabra before the massive deity, clanging a handheld bell and chanting in a booming, nasal voice. Upon descending, he walked the flames around the group, each of us cupping our palms a safe distance away, then lightly touching our eyes to close the circuit of divinity: Idol. Flame. Human.

Back on the vast courtyard, we began our pradakshinam, the ritual circling of the central tower. Walking the temple grounds, I felt instantly at home. I knew I had been to this temple before, as a baby, but this was more than inchoate infantile memories. I felt the first time my parents came here as a married couple. I felt the moment I was born, just a few hundred yards away. I felt the day my father and his family came to my maternal grandparents’ home for the penn paakarthu (girl seeing) ceremony, to decide whether he should marry her. So much of my generational history was wrapped up in this city, and this city was inextricable from this temple. The rest of India required interpretation. Periya kovil felt as natural and familiar as my name.

The last stop was a low-slung, rectangular shrine where frescoes dotted the ceiling. We walked through the shrine to the sanctum, which housed a female idol named Brihadaambal (great goddess), Brihadeeswar’s consort. We gathered her blessings, too, and trooped out to the courtyard, where we sat for a few minutes before catching autos back home. I was reluctant to go.

Peirya Kovil, like Thanjavur itself, was the India I had hoped for. The Taj Mahal had been closed for renovations. The relatives had been friendly but distant. But here, at Rajarajeswaram, I felt intrinsically, effortlessly connected to my heritage. I wanted to learn everything about this place, to read every layer of history in the sunbaked stones beneath my feet—my history, my family’s history. In this place, I belonged to the country that my parents called home. I felt it had been inside me all along.

***

In 2014, two scientists set out to answer a question: could experiences be passed from parents to offspring? The query seems straightforward enough, but it was part of a scientific controversy that predates Charles Darwin. For over a century, the prevailing wisdom had been that creatures could only inherit intrinsic traits, things like eye color and hair color. Experiences, on the other hand, could not be passed down. You cannot inherit your father’s talent for cooking, your mother’s interest in Shakespeare.

But by the time Dias and Ressler began their experiments, a curious body of evidence had begun to accumulate. Waterland and Jirtle found that when mice consumed certain dietary supplements pre-pregnancy, their babies’ coats were deep brown instead of speckled with yellow. Champagne and Meaney showed that pregnant rat mothers subjected to stress produced offspring who were more anxious than their stress-free peers.

Dias and Ressler wanted to go further. Could a creature’s life experiences, before conception, directly influence its offspring’s behavior? To find out, they exposed male mice to acetophenone, a floral fragrance. This scent is detected by a solitary olfactory receptor, called M71. They constructed an elegant experiment: if they taught mice to fear the scent of acetophenone, they could look for evidence of this trait in their offspring, not only through behavior, but also through overgrowth of the M71 receptors in their brains.

Fear was conditioned by releasing acetophenone into the cages, then delivering a small shock to the mouse’s paw. Then the fearful mice were mated with regular females, and their sons were studied. They had never smelled acetophenone, yet when that floral scent preceded a loud noise, they jumped much higher than in response to a loud noise alone. Dissection revealed that they, like their fathers, had thickly cultivated M71 regions in their brains, tendriling outward like generous clumps of saffron. Before being dissected, these sons mated with regular females and produced grandsons. Like their fathers and grandfathers before them, these grandsons seemed to fear the fragrance of acetophenone, and their brains exhibited the telltale M71 overgrowth.

In the end, these experiments provided evidence that “ancestral experience before conception” could influence adult behavior. That is to say, we can learn from what our parents experienced before we were even born. We can fear what our mothers learned to fear, love the foods our father learned to love. After all, if negative experiences can be passed down, so too, surely, can positive ones. Our brains are a palimpsest of remembrances, stacked like Russian nesting dolls. Perhaps every moment of déjà vu is actually a memory our parents once made. Perhaps we have been here before.

Thanjavur is my birthplace because my maternal grandparents lived there. Following regional tradition, my mother came to her mother’s home when it was time for her to give birth. The tradition is eminently practical—childbirth is exhausting, early motherhood bewildering. South Indian women come home so their own mothers can help. She bore her into existence. She will bear her into maternity.

And so in her eighth month of pregnancy, my mother boarded a train from Bangalore to Thanjavur, and came home. I conjure her in my mind’s eye, thin limbs and full belly, holding my older sister’s hand and walking through the train station, riding a sputtering auto across town before crossing her mother’s doorstep and finally letting go my sister’s hand so that her brothers and parents could envelop her daughter in hugs and kisses. She is achy and tired, but relief floods her, the same relief I feel in my mother’s home: She is here. She will take care of me.

Soon, I came squalling into the world after, as my mother proudly notes, a “totally natural” delivery. There were no analgesics, no new-age birth mixes, no cheerleading family members. Just my mother, the occasional doctor or nurse who reassured her that the pain was normal, and, eventually, me. I was bundled back to my grandparents’ home, where my suddenly jealous sister demanded, in no uncertain terms, that I be taken back to the hospital.

On my thirteenth day in this world, my parents named me: Chaya. The name, short and uncomplicated, means shadow. I am told that my father loved the name, landed upon it before I was even born, when my gender was unknown.

As a little girl, I didn’t fancy the name “shadow,” and preferred the expanded version of my name, unfurling from my tongue like a hidden secret: Chaya Tharangini. The double name sounded trilling, delicate, coy. Tharanginis are a collection of Indian classical songs; Chaya Tharangini is an infrequently employed raaga (key) in classical Indian music. My unraveled name connected me to my paternal grandmother, a singer, who suggested it.

During the naming ceremony, the father whispers his child’s name in her ear. I imagine my slender, teak-skinned, mustachioed father leaning over a small wooden cradle, mustache tickling my ear as he breathed my identity into existence: Chaya Tharangini. What I did not know until many years later was that he also whispered another name: Brihadaambal.

***

In 1809, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck published a book called Philosophie Zoologique. He wrote a great many things in the book, but what history remembers most is his theories on inheritance. Lamarck believed that humans and animals could inherit acquired traits from their parents. Think about this for a moment, because it doesn’t sound outlandish at first—according to Lamarck, we could inherit our grandmother’s arthritic limp, our father’s obsession with coin-collecting, our mother’s callused hands. Or, as Lamarck’s most famous example went, giraffes inherited their long necks from ancestors who stretched to reach high leaves on Serengeti trees.

In Lamarck’s imagining, early giraffes had necks no longer than horses’. They roamed African plains searching for vegetation, but they were physically limited to only low-hanging leaves. But one day, a few ancestral giraffes, particularly hungry and particularly persistent, craned their necks to reach higher leaves. Those short-necked ancestors craned and craned until their necks actually elongated. The taller giraffes ate better than the others, leading to a competitive advantage. They were able to reproduce more and, (here’s the Lamarckian twist) their offspring were born with long necks. This sequence of events repeated for several hundred generations, transforming giraffes into the species we know today.

When you think about it, this idea is attractive. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could emerge into the world with heads full of lessons from our parents’ mistakes? In his time, Lamarck’s theories were welcomed. People liked the idea that their own striving could improve their children’s lives.

But fifty years after Philosophie Zoologique, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, and his theories quickly superseded the old ideas. Fossil evidence bore out Darwin’s proposition. So did DNA. Lamarck became one of the famous laughingstocks of scientific history, a man with fantastic ideas about inheritance, a man who had been wrong. Experience was not heritable.

And yet. Evidence now abounds about the influence that parental experience has on offspring’s intrinsic traits. Mice fear the smell that portended a painful shock to their grandfathers’ paws. Rats whose mothers neglected them are more anxious in adulthood, and become neglectful mothers themselves. Maybe Lamarck wasn’t a flawed scientist after all, but a visionary. He saw something that others didn’t see. He saw a giraffe’s neck stretching forward in time.

***

I was seventeen years old when I learned my secret name. My parents and I had come to our local temple in Houston, a semi-open-air structure with pure-white gopurams and vimanas, tiny compared to Rajarajeswaram. We were inside the central temple building, where my parents had asked the priest to conduct an archana, a ceremony invoking blessings for each member of the family. There is a formula to the ritual. The priest chants a few prayers in his sonorous voice, collects fruits and flowers onto a plate, and stands before us. Our fingers graze the edges of the plate, indicating that we are offering its contents to the lord. The priest says “gothram?” and looks expectantly at my mother. She provides the name of our family clan. He repeats it, tacking on a few Sanskrit words to declare our lineage to god. Next comes my father’s birth star, then his name, my mother’s birth star, then her name, my sister’s, and mine.

I’ve experienced the ritual dozens of times. Its predictable script, the familiar cadence of my mother’s responses and the priest’s intonations, the sense of being formally announced like a member of the peerage entering a royal ball, I find these things soothing. I enjoy listening to my heritage being traced out loud, from the ancient sage who gave his name to our family clan to my parents to my sister to me, all of it in turn reflected back to the divine in a string of identity and inheritance. My mother likes to use the most formal versions of our names for archana. Murali becomes Muralidhara Sharma. Swathi becomes Swathishta. Chaya becomes Chaya Tharangini. [Her own name, Lalitha, has no extension.] This titular elongation feels appropriate, like standing up straight to show respect.

On that day, the archana followed the usual trajectory, until we got to the space where my name belonged. Instead of Chaya Tharangini, my mother uttered a word I had no memory of: Brihadaambal. The priest repeated this unfamiliar name, then walked back to the idol with the tray of fruits and flowers, chanting prayers with the speed of an auctioneer. Though brimming with curiosity, I had to keep quiet until the ceremony was over.

Afterward, we trooped on through the humble temple complex, visiting two more shrines to complete our circuit. I scurried behind my mother, waiting impatiently as she greeted old friends and inquired after their parents and children, until I had the chance to interrogate her:

What was that name you said earlier?

Oh, that? She replied breezily, in Tamil. That is your name only.

I sputtered my protest—No it isn’t, I’ve never heard that name before.

Of course you have, she insisted casually. It’s the name of the goddess of Periya Kovil. I dimly recalled that the Shiva at Periya Kovil had a complex Sanskrit name, Bri-something, but I was certain that my mother had never taught me his consort’s name, instead always referring to her as Ambaal, the generic name for a female deity. Oblivious to my confusion, she went on. We gave you that name to remind you where you come from, just like your sister and cousins. All of you have ceremonial names, from temples in Thanjavur, or from ancestors.

I took mental stock: my mother sometimes called my sister Swarna Kamakshi, for the gold-armed goddess of another Thanjavur temple. My cousin Sridhar was also Kamalan, a masculinized version of our grandmother’s name. Indeed, most of my relatives were binomial, their daily and ceremonial names markedly distinct. My name only stretched. But now it had transmuted.

The exchange was just like so many others I’ve had with my mother. I ask a question, she gives an answer that knocks me flat on my back, she’s mildly bemused at my surprise, then casually moves on to the next topic while I try to pick myself up. It happened when she reported that her parents are second-degree relatives by blood. It happened when she taught me about the caste system.

I think the intensity of this generational call-and-response is possible only in immigrant families. When you are surrounded by a norm so utterly different from your parents’ upbringing, is it any wonder that every cultural lesson feels like a collective secret?

It was only later that I reflected on this secret name’s significance. When I had clambered atop that elephant in the outer courtyard, when I had craned my neck to look inside those grilled windows on the first gopuram, when I had stared awestruck at the countless carvings and prayed before the gargantuan deity, when I had visited that low-slung hall and seen a female idol, when I had felt, both inexplicably and undeniably, connected to Rajarajeswaram, of which I had no memory—all along, this place had been inside me, written upon my very existence with my father’s whisper. Another entry on the palimpsest. Time compressing to lay past upon present.

Rajaraja Chola is standing on a paved courtyard, gazing at a thin pyramidal tower. He is fifty-six years old. He has worn his kingdom’s crown for twenty-five years, and in that time he has expanded the Chola Empire masterfully, from Cheralam in the west to Lanka in the south, even annexing Kalinga in the north. His conquests have earned him the name he assumed when he ascended to the throne: Rajaraja – King of Kings. But many years ago, his thirst for military engagements was quenched, and he had turned to religion.

Like his ancestors, Rajaraja is a great devotee of Lord Shiva. He has patronized singers of the old hymns, spreading their glory throughout his kingdom. He has worshipped at Chidambaram, the great Nataraja temple that was favored by his forebears. His devotion is as vast as his territory, and so he decided to build a temple to match it. The temple would be larger than any the world had seen, as glorious as his empire, and it would be located in his beloved capital, Thanjavur.

Thousands of artisans and laborers were employed. The granite was quarried from thirty miles away and dragged to the site by teams of elephants. The gopurams and the central vimana grew upward, and sculptors covered every visible surface in carvings. Most extolled Shiva, but others reflected the diversity and tolerance of his kingdom: the images of Buddha, the panels depicting legends of Vishnu. Exquisite frescoes were painted.

As he surveys this complex he has commissioned, Rajaraja feels pleased. He and his family have donated richly to the temple, and Grantham inscriptions bear witness to their generosity. He has set aside money for every necessity, from camphor and cardamom to buffalo, sheep, and cows to provide dairy. He has created whole neighborhoods for the musicians, priests, servants, accountants, treasurers, carpenters, and dancers who will serve the temple, and provided for their salaries. Over four hundred pounds of gold, five hundred pounds of silver, and countless jewels have been provisioned to adorn the idols in great splendor. No detail has been overlooked. No expense has been spared.

On the 257th day of the year 1010, Rajaraja bathes the temple spire with water from the sacred rivers of the Chola Empire. The grand opening. Rajarajeswaram, this monument to his devotion and his empire’s greatness, is now a living place.

Rajaraja cannot know what will happen in this place that bears his name. He does not know how the beautiful frescoes will be covered, centuries later, by new artwork commissioned by kings from another dynasty. He does not know that the original Nandi he oversaw will eventually be dwarfed by another, a hulking display of devotion and greatness. He cannot know that invaders with white skin will briefly commandeer his beautiful gopurams for a garrison, how Mughals will damage this complex but never succeed in destroying it.

But even as his temple becomes a palimpsest, it remains, a piece out of history, a physical chain linking past to present, a tactile, visual, olfactory memory of where we have been and how far we have come.

A giraffe’s neck stretches forward through history. A mouse’s life lessons are imprinted on his sons and grandsons. A woman affirms the identity she has always felt inside her. An emperor’s legacy lives on.

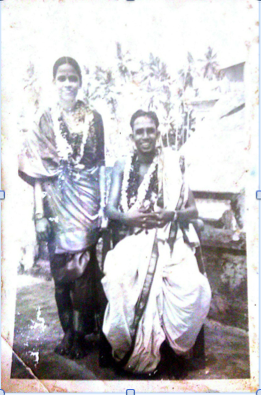

Image Credits: Edna Winti

Chaya Murali is a pediatric geneticist and personal essayist living in Houston. Her work has appeared in Crack the Spine and Entropy, and her essay Bits and Pieces was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2012. She attended the Bread Loaf Writer's Conference in 2018. Chaya writes about identity, inheritance, family, and genetics. She loves cooking, hates cilantro, and can be found musing on food and culture at instagram.com/akkashouse