I heard Opa’s last words before he died. I don’t think I deserved to be the one. Ma was the one who fed him and washed his genitals and treated the sores on his back and legs. She claims to have been the closest to him of his three children. She told him her secrets, she says, and he trusted her with his. He was closer to his other grandchildren. I, on the other hand, wasn’t particularly affectionate with him.

On some nights when I stayed over, while Oma was showering and Opa watched baseball, I’d climb into their bed and rest my head on his chest. I stared at his crossed feet, crooked in his white, ankle-length socks. Ma says her feet were identical to his except Opa’s were more crooked because his boots were too tight when he was a kid and he couldn’t buy another pair. I’d listen to the tha, thump, tha, thump of his heart, his ribs warm and solid under the worn fabric of his cotton shirt and wonder if I’d remember the sound after he died. Opa was the oldest person I knew.

The day of his wake, the Opa in the coffin didn’t look like Opa. I’d never noticed his eyelashes being that blond. His lips were pressed tight in a grimace. Ma says the guys from the funeral home must’ve glued them together.

I wonder how they got his mouth to close. When we arrived at Oma’s house that morning, Opa had his mouth open, as if he’d died mid-yawn. A fly darted about the room, lingering over the bed. I worried it would sneak into Opa’s mouth if we weren’t careful, get stuck in his throat. Tía Ilde closed his eyes, which were fixed on the wall, but she couldn’t get his mouth to close. Then the neighbor tried when she came to pray the rosary. She placed one hand on his head and the other under his chin, but Opa’s jaws wouldn’t close.

I thought her bold. Almost rude. If Opa were alive, she wouldn’t have dared place a hand on his face. Opa was an intimidating man.

When Ma and Pa went on business trips and I stayed over at Opa and Oma’s place, Opa was the one to wake me up for school. Before my alarm clock went off, I’d hear his leather slippers on the tiled hallway. When the door creaked open, I’d press my eyes shut, pretending I was asleep. He’d leave the door open, and then his slippers would move away. Later, I’d hear the coins in his pant pockets and knew he’d gotten dressed. If I dared open my eyes, I’d find him in the bedroom doorway, staring at me with impatience, with fury, almost with panic. He’d hold up his wrist and hit the face of his watch—click, click, click. If I didn’t get up, he’d fetch Oma, who’d come into my room in her nightgown. She’d take my hands and guide me to the bathroom, where she’d place them under running cold water to help wake me up.

I don’t know why Opa didn’t move past the bedroom doorway—why he wouldn’t sit next to me in bed and take my hands like Oma did. I hated that we were fifteen, twenty minutes early to school, anyway, which left me to roam the empty hallways like a loser. Ma says Opa was like that—anxious and painstakingly punctual—because of the war. He came to Venezuela after World War II with a bomb shard stuck in his leg. He was twelve and didn’t know how to speak Spanish.

“Can you imagine?” Ma asked. “Getting here and not knowing the language?”

But that was something hard for me to imagine. What I did imagine was Opa as a boy, painting lamp posts on the highway. Oma told me a German man had hired Opa and other boys who didn’t know Spanish. One morning, el general Marcos Pérez Jiménez himself came to supervise their work. The sun hadn’t come out when el general asked, “Are you cold, boys?” and offered them each a drink of brandy straight from his flask. I imagine Opa smiling under the lamppost, proud that el general had treated him like a man.

* * *

The morning Opa died, I woke to the sound of the light switch in the hallway and saw Ma in my bedroom door, a shadow against the light.

“Nina,” she said and shuffled into my room, hugging her night robe. The mattress bent under her weight as she sat next to me.

“Opa died,” she said and sniffled into my shoulder. I tried to sit up, to hold her, but Ma straightened, composing herself again.

“Let’s go and help Oma?”

The thought of Oma filled me with dread. I’d seen the way she pressed her lips and looked away when Opa struggled up the stairs. She refused to leave the house, wanting to be there when the moment came. I thought she’d be relieved the moment had finally come, but when the two men with the stretcher climbed her stairs and zipped Opa up in a black leather bag, just like they’d zip up a suit, she screamed, “They’re taking him! They’re taking him from me!”

I clung to her waist and said, “He’s no longer here, Oma. He’s resting. He’s finally resting now,” which was code for, You can rest, too, Oma. You can leave the house and come to my tennis matches and go to the movies with us and have coffee at our place, but my words didn’t comfort her.

When people hugged us and said that Opa was a good man, I couldn’t help but wonder if they knew; if they knew he drove with a beer bottle between his thighs the day he met Oma, and that, once married, he’d invite his friends to play dominoes in their walk-in closet and Oma had to get on her hands and knees the following day and scrub the beer off the carpet and wash all the smoke-smelling clothes again. One day, tía Ilde told me, Oma found lipstick stains on Opa’s shirt collar and ripped the shirt and threw the shreds out the window yelling, “I’m not washing these bitches’ shirts!” He drove so drunk down the highway, tía Ilde thought the lampposts were bending and Opa had to pull over to puke.

Ma says those were different times. She doesn’t like when tía Ilde tells these stories. When Pa was alive, Ma liked to ask why he couldn’t be as spontaneous as Opa, who arrived from work with chocolates in his shirt pocket for his daughters, or cakes for his grandchildren’s birthday parties. Who surprised Oma with a bouquet of flowers on any given day and asked her to dance after dinner in the basement while Ma and tía Ilde watched them, hidden, from the stairway. For Ma, Opa will always be the most charming man.

* * *

Ma always said that, for wakes, one dresses in black out of respect for the dead. Before Pa died, Ma went to wakes in heels, pearls, and perfume. After Pa died, she stopped going to wakes until this one. For Opa’s wake, Ma wore the same blue shirt and white pants she’d put on that morning; she’d got caught up in all the paperwork and never had time to go back and change.

The guys from the funeral home dressed Opa in his blue suit. The black one wasn’t ironed, so tía Ilde and Ma chose the darkest one he had. With the coffin open to his waist, we could only see his jacket, shirt and tie. We couldn’t really know if he had pants on or if they put on his dress shoes—for all we know, they could’ve stolen them. We had to imagine his legs there, resting under the wood. For all we know, he could’ve been a merman.

More than once, when Opa was alive but could no longer get out of bed, Ma showed me the scar the bomb shard left on his shin. When he was a kid, Opa was helping to load bombs when one went off close by and a shard got stuck in his leg. He didn’t notice it until he felt blood pool in his boot.

Opa’s legs were full of freckles and sunspots. As soon as Ma pointed out the scar, I’d lose it again.

* * *

In the coffin, the only thing that still looked like Opa was his thumb. If you looked closely enough, you could still see the yellow stain he got from holding his medicine pills for too long before swallowing them.

Ma loves to say her thumb looked just like Opa’s. It did look like his, especially the half-moon at the base of his nail.

* * *

Opa’s car—a military green Lincoln Continental—had soft leather seats and always smelled of baked bread. He kept a red apple on his nightstand that he liked to eat before bed and a stash of dark chocolate in his night drawer. When he wasn’t home from work, and we were still over for afternoon coffee, I’d sneak into his room, open the drawer and take a square. Opa never said anything. I felt it was our little secret.

* * *

The week before Opa died, we drank coffee in Oma’s second floor parlor. The nurse and Ma helped Opa into his plastic chair and tucked a small towel into his shirt collar like a bib. He had his comb in his shirt pocket, as he always did. He could no longer comb his hair, but he kept patting his chest to make sure it was still there. We watched as Ma played songs for him—Julio Iglesias and Elvis Presley, the ones he liked. Ma grabbed his hands and swayed with him as if they were dancing. Sometimes, Opa remembered the songs and hummed along. But that afternoon, Opa mostly stared out at the avocado tree and picked invisible spider webs off his legs with shaky hands, lost in a world we couldn’t see.

When it was time for dinner, Ma and the nurse helped him upstairs. The nurse took his left arm in the crux of her elbow, and Ma guided his right hand over the railing, pushing him from behind. She counted the steps for him, “Uno… dos…”

A few months before, Opa would’ve yelled, “Coño Heidi! Don’t push me!” but that night he only muttered, “Ay… ay… ay…”

I stayed with Oma and tía Ilde in the parlor, looking through my phone while Ma fed him. When Ma came downstairs with the tray and the soup bowl half full, she nodded up the stairs and asked me to say goodbye.

I found Opa on his side of the bed. The lamp shone on the small kingdom of pill organizers and water glasses on his night table. The nurse sat in a plastic chair by Oma’s side of the bed, where she had a better view of the TV. With pillows, they had propped Opa up so he could watch, too—though, if Opa were truly Opa, he’d be watching baseball and not a comedy show. Yet Opa didn’t seem to be watching the television but the wall behind it. Whenever he got lost like that, or called us names of the no longer living, or spoke to us in a German only he understood, I wondered if he’d gone back to being that boy who’d lived through cold, remote winters. I imagined him with chubby cheeks and a beret, like I imagined children in the Second World War, walking through snowy slopes to the train station where he’d wait for his dad to come back from the front, as he did for three years until he finally came back.

I sat in the chair where Ma fed him his food. I took his coarse, freckled hand and leaned in to give him a kiss.

“Chao, Opa,” I said.

He squeezed my hand.

When I leaned back, his eyes searched mine. He seemed to be looking at me—really looking.

“Ah, no,” I said, “Don’t be sad. Mira que I’ll be back tomorrow with Ma.”

“You have to be strong, chiquita.”

I sat still. I wasn’t sure if he knew it was me or if he thought I was tía Ilde or Ma.

“You have to be strong,” he said again and squeezed my hand tighter.

His eyes watered. My eyes watered too. I hugged him.

On the TV, the audience laughed.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I’ll be back tomorrow with Ma, okay?”

I gave him a kiss on his stubbled cheek. I got up and turned for the door before the nurse could see me cry. She took my place on the chair.

“My eyes itch,” Opa said, reaching for her.

“Yes,” the nurse said. She took the towel from his shirt collar and wiped away his tears.

* * *

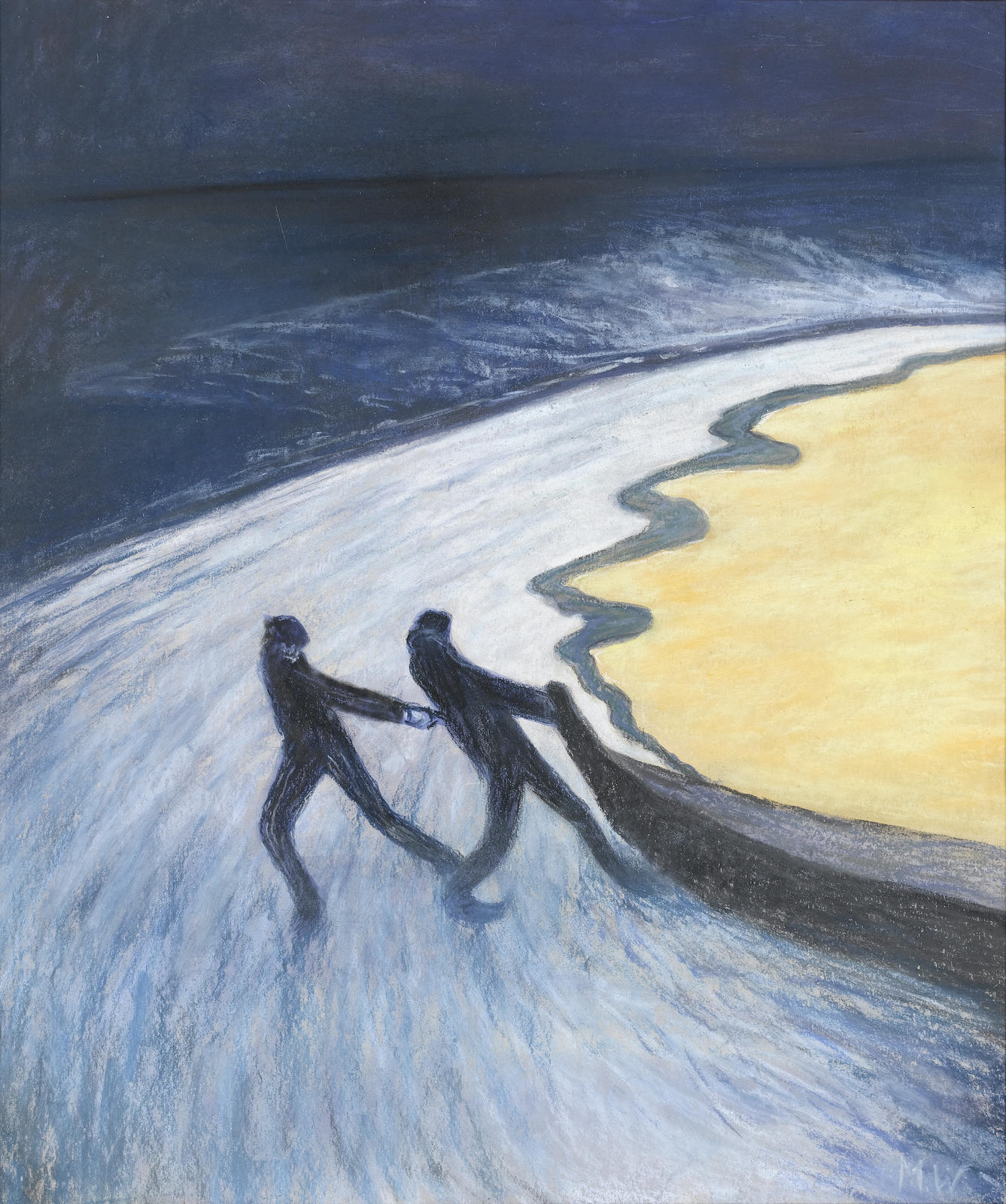

Image credit to Marianne Von Werefkin via OAI

Cristina Herrera Mezgravis is a writer and educator from Valencia, Venezuela. She graduated from Stanford University with awards in both fiction and nonfiction. She worked in tech and in college prep in the Bay Area and in Lima, Peru. She currently lives in Austin, Texas with her husband and their tabby cat, Lima. As a second-year MFA candidate at the Michener Center for Writers, Cristina is working on a coming-of-age novel about Venezuelan migrants.