In Fall 2023 I had the pleasure to speak to Diana Khoi Nguyen about her work and learn more about her creative genealogies. In preparation for our conversation she shared an essay she turns to regularly: Lana Turner: A Journal of Poetry and Opinion. We began by asking, what does it mean to be in a proto revolutionary moment, one of urgency, anxiety and uncertainty? What does it mean to be in conversation with the left wing avant garde?

Diana Khoi Nguyen: This text is from 2012, but it’s one that I return to because Cal Bedient was my mentor when I was an undergrad. Whenever I don’t know what to do in regards to writing, especially when I have an existential crisis, I reread that interview and I ask myself, what does Cal want, as in: what poetry does Cal want in the world? It’s not just that the writing has to be experimental, but it’s more like, what is the capacity for what one can do. I think about that and it helps me to try stuff I wouldn’t normally try.

I don’t feel like I’m as political as Lana Turner. But I wonder, how could I write something that’s political for me that they would call political too? It’s my touchstone. I went to Columbia for my MFA and I studied with somebody the opposite of Cal. When Lucie Brock-Broido liked a poem, she drew a unicorn. That’s how you knew that she really loved the poem. Like you never saw Lucie when the sun was out, you didn’t know what size her body was because her clothes were voluminous. Inside her house, it was all red velvet. I spent a lot of time with her. And she loved a high, lyrical beauty in poem, and also liked truth. Duende.

I shared that interview because after my MFA, I kept writing poems with my mentors in mind. But then I was like, Why do I care what Lucie or Cal thinks? After graduating, I finally asked, what does Diana want? I knew I was political, but I just didn’t know how. I needed to find a middle ground: I needed to not be in any one place but to find my own place.

This is a roundabout way of answering the question about that interview. I do agree with this notion of challenging language. It’s so hard to make stuff new without it being a gimmick. Because I write every six months, I’m regularly like, “I don’t know what to do.” And then I go back and I read the interview, try not to email Cal, to ask him to tell me to do something, like give me a prompt because sometimes he does. So yeah, I turn to Lana Turner also because there is all this other political stuff in there–yes, capitalism is dangerous, but I’m not sure I want to articulate that in a poem. I don’t understand all of the journal’s work, but it excites me and it gets me to want to create. Like how the best kind of reading makes you want to go home and explode shit, not literally make bombs, but to try wild stuff on the page. Stuff that feel incendiary.

AC: I am very excited to know that there is literary journal that publishes works that compels us to want to throw the journal across the room.

DKN Yes.

AC: And that is resistance. To publish work that explodes something in us, in how we see the world. It makes me think of your poem, “Triptych” from your beautiful poetry collection, Ghost Of where you say, “do not simply resist, resist; we who are free to move around who are free, bewilder, we bewilder what we fill in what bewilders us to fill in what” When I read the word bewilder, I heard Be wilder.

DKN: I love that. Be wilder.

AC: Teresita Fernandez, a Cuban visual artist, was asked, “what is your aesthetic?” And she said, “well, aesthetic. Is this just awareness? The definition of the root of aesthetic is to be fully aware.” So my question is, when did you find your aesthetic?

DKN: That “Triptych” poem you mention was the first one I did. I’d gone to sleep the night before, rereading that Lana Turner interview, distressed, thinking I’ll never write again. I can’t write anything that is helpful. So the next day I asked myself, what am I not talking about? I mean, I’m a person who’s very transparent. I’ll share everything with you. But even so, there’s still things I’m avoiding. For instance: I couldn’t look at these pictures that were still hanging in my family’s house. They’re fucking scary. I had to ask my sister to scan and send them to me. And when you scan stuff and then put it in a Word document it’s ginormous. But it wasn’t so scary when I opened the file up because it could be zoomed on somebody’s shoe. A 1994 shoe is a lot less scary than a portrait of a family with a brother cut out of it. And then I slowly began to zoom out. Then I could hold it. When it became overwhelming I would move to another part of the picture.

This may not be writing, But this is still part of the practice. This is a big part of my practice even now, even when I don’t work with an image within a piece.

Think about what’s on your desk when you’re writing, authors, the books, what objects, what’s at the altar, the desk. I literally push it as a watermark in the page, like I’m writing over ancestors and I just remove the image later. It’s like writing with ghosts. They’re there to second guess: what are their stories and what do I remember about them or what I do not know about them. I now welcome the practice of Tina Campt, whose work I love. She has a book where she’s working primarily with images within the Black diaspora, Listening to Images. It’s auto-ethnographic. She talks about how images emit a frequency that we cannot hear but we can feel. Like sound waves! For example, my voice right now is only disappearing and people can’t hear it outside because all your bodies, the carpet, the walls, the wood, the concrete is absorbing that sound. The image, which is seemingly inert, is also emitting. It’s communicating to us in some way and sometimes we can pick up on it. And when we can, what are we going to do with what we feel? This is another way of asking what draws you to a particular visual element and what do I have to say about it? A lot of times it’s not necessarily drastic in describing what I’m feeling, but sometimes to the ghosts and ancestors I sense around me, I’m like, “Hey guys, come on in. Let’s type together.” The writing becomes collaborative, it’s also a family, also a diasporic documentary. Writing at first made me feel uncomfortable. I couldn’t look at the images my brother left behind until a year after this death. I hadn’t cried since I got the phone call that he died. I didn’t cry at the funeral because it all felt so was weird. I didn’t have access to how I felt. The images scared me. So I had to break down the scary thing into tasks: for example, putting a text box over the dead brother’s white cutout space and filling it in with text–the cutout space determining the line breaks. After doing that, I realized I had much more to say. So I asked myself, what if poetry or what if creative writing could be a framework around the person who no longer exists? Then I wrote over the photograph and around the cutout space, text hugging the void. As I did that, I started crying, and it seemed that the floodgates opened up from inside. I had no idea that would happen. That white space was a key hole which unlocked pent-up emotions from over a year. When I consciously and intentionally decided to stay and write in the cutout space, it gave me access to all these things I didn’t yet know how to engage with.

Family documents give me access to more of myself and other parts of family narratives. I continue to collaborate with images. I often wonder, what else can photographs unlock for me? Before, I used to hope that a poem would arrive, especially during grad school; often I’d hope for a good dream the night before a poem deadline.

Now, I’ll make a gardening analogy because I’m currently working to remove the monocrop sod in my backyard. I want to plant native and indigenous plants so that bees and butterflies native to the region can come, eat, and thrive. But I’d like to do that with my imagination too. What other books can I nourish it with? During the writing of Ghost Of, I fertilized my imagination with materials around the theme of dust. I watched movies, read scientific papers, nonfiction, fiction, things that I wouldn’t normally pick up, and consumed materials that were both tangentially or directly related to dust. I took notes, but also wasn’t trying to directly write about dust. This fodder gave me access to metaphors, similes, and diction that I wouldn’t normally have. This approach continues to give me a way to continue being a student long after I’ve graduated. This is all part of my aesthetic now: how can I continue to pollinate and fertilize whatever this patch of earth is (that is my brain)?. What new crop do I want to plant and how might I prepare the field for it? There’s a lot of labor involved in preparation. Sometimes I don’t know what it is I need to say, but I can give myself a foraging basket and use the foraged words and images to begin to put stuff down. The writing process is one of much preparation, and one of unending discovery.

AC: It’s not that different from my creative process. I spent many, many months waiting for inspiration. As I’m listening to you, I’m thinking about that moment when one is fully aware of the thing that unlocks creativity. I like to be invited to do things that are outside my wheelhouse because, I’ll try something I don’t know a lot about and think, it’s okay if I fail miserably, at least I tried at something. Can you tell me more about the ways that you collaborate and work anonymously with your collective?

DKN: I’m part of this female and non-binary Vietnamese diasporic artist collective called She Who Has No Master(s). The work we make doesn’t have an author. The author is the collective, but everybody contributes to it. It’s not just: I (as an individual) am gonna write something. And it’s also not an exquisite corpse. The collective shared document is amorphous and sometimes filled with chaos. And yet, at any juncture, when you look at any shared document we have, it’s incredible because there’s something so powerful a force when you’re an anonymous Google animal on the shared doc. And in that Google Doc, you could say a terrifying thing and it can’t be traced back to you. And it’s this power within the collective that prompts us. It’s not trauma porn or trauma that I’m offloading, but something more along the lines of how we don’t skirt away from the thing that is scary to mirror back to me. This is the diasporic experience. It’s deeply powerful. You don’t know who wrote it down, but you recognize truth on the page. Seeing these truths makes you feel safer to share your own truths, and you’re safe because the public would never know who said what. It’s a unique kind of power and beauty.

We have people who are artists, prose writers, poets, and also scholars. Everybody’s got their own way of making and composing and it’s so weirdly wonderful and delicious. Liberating. The collective is a safe space where nobody’s trying to out-do anyone else; it’s non-hierarchical and also–nobody’s watching. Nobody knows what you did.

Any opportunity or invitation an individual collective member receives, generally turns into an invitation of the collective. For instance: my initiation into the collective was a situation in which I inquired and invited the collective to participate in an exhibit with me.

Someone I’d met on social media years ago was now living in Salt Lake City and curating for a small gallery there. When I was finishing up my PhD, this curator asked if I’d like to exhibit part of my dissertation. Instead of saying yes, I asked if I could invite She Who Has No Master(s) to engage in some core components of the work I’d been exploring. And the curator was enthusiastic about the idea–so then I wrote to SWHNM to see if they wanted to collaborate, and I’ve been a member ever since.

AC: It’s a wonderful model! Working anonymously within a collective is a way of sharing power and resources. It also destabilizes hierarchies around who is more established or emerging.

DKN: A student once asked me for permission. They asked, “I was reading your book and I want to do these body image-text things. Can I do that and just write, “after Diana Khoi Nguyen?” I replied, “There’s no need for the ‘after’– you can just do it, and it’ll be your own thing.” I mean, I definitely didn’t invent concrete poetry! Nonproprietary forms!

This is actually the opposite of how I feel grad school was: every writer trying to do their best at being the most unique or something. Which has some utility, but also, is really unhealthy. I had a friend who would withheld submission and contest information, not share submission deadlines, I think because she thought she had a better chance of winning if less people submitted. Which is such a scarcity mindset.

That’s such a shame, because, that’s not how it works. Community is vital for the writing life. It works if we all share, generate, and contribute to the hive. Every time someone wins, or succeeds, we celebrate these moments collectively. If I didn’t win something, I’m just happy that someone I knew and admired won! And then I believe that I’ll a little closer to being hopefully winning / receiving this opportunity (or one like it) in the future.

How to retain and nourish the spirit of generosity and good will within a collective? We have to be anti-capitalist and secretive. Doing so breeds many bad feelings and it makes it harder for one to write because one just feels shitty. And I don’t want to feel shitty. I want to celebrate people, get excited, be inspired, then go home and do something explosive on the page. Then do it again and continue advocating for others in my various communities. I’m also thinking: What can I draw forth from other people, and how can I nudge people if I haven’t been seeing them doing something (like writing)?

For instance, If I see someone has a proclivity or potential for trying a different genre or modality, I bring up this possibility to them. Encouragement can have surprising effects. Sometimes I’ll invite a writer to do a video with no sound (nothing fancy, just with their smart phone). And no one has asked them to do that before. So they do it, and then it leads to X, Y, and Z, and then like later down the chain of reactions, it will have like sparked a different kind of move in their short story or project. Which brings me to a vital aspect of my aesthetic, which is play. How do we get back to that early place of possibility–when we were kids in the sandbox? How to not be bogged down by doubt.

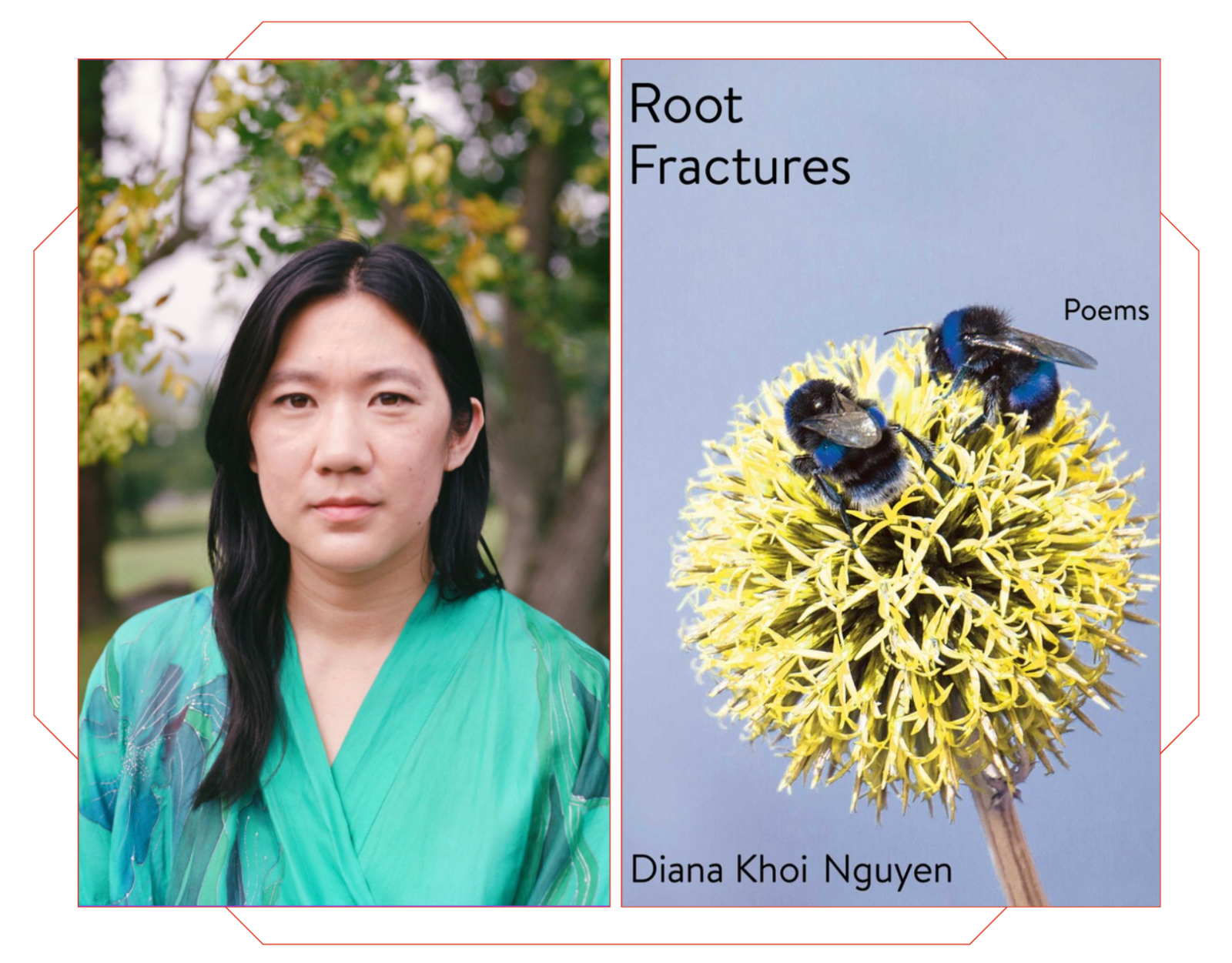

AC: Before we end our conversation I wanted to ask you about your most recent book, Root Fractures and how you begin with Vietnamese, a language you continue to study. I am curious about your relationship to Vietnamese and how it informs your work.

DKN: Before I answer this, I have to share a bit of context: I didn’t know that Vietnamese was my first language until I watched a home video of myself as a three year old bossing everybody around, take pictures of the family in a slang-y southern Vietnamese dialect. When I started Kindergarten, my parents forbid me from speaking Vietnamese; I spoke English even when my parents spoke in Vietnamese. And then throughout my adolescence, I felt shame at not being able to speak Vietnamese around relatives.

Fast forward several years to just before the pandemic: I traveled to Saigon and began tutoring lessons with a native speaker and instructor. One of the homework questions was: Write a paragraph for your family. Immediately, I thought, “Oh, shit, I don’t even know how to say all the things I need to say yet to respond to this assignment.” And with my limited three weeks lessons, all I can write are elementary sentences such as, We are five, So-and-so is an architect or So-and-so is an engineer.

There’s so much I don’t know how to say or write–like the word for suicide.

Doing this assignment put me in this weird intersection being unable to articulate fully while feeling so much on the inside–all while trying to learn a language which I used to know. So many layers!

A poet and multimedia artist, Diana Khoi Nguyen is the author of Ghost Of (2018) which was a finalist for the National Book Award, and Root Fractures (2024). Her video work has recently been exhibited at the Miller Institute for Contemporary Art. Nguyen is a Kundiman fellow and member of the Vietnamese artist collective, She Who Has No Master(s). A recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and winner of the 92Y Discovery Poetry Contest and 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, she currently teaches in the Randolph College Low-Residency MFA and is an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

Angie Cruz's novel, DOMINICANA is the inaugural bookpick for GMA book club, and the Wordup Uptown Reads selection for 2019. It was also longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie award in excellence in fiction for 2019. It was named most anticipated/ best book in 2019 by Time, Newsweek, People, Oprah Magazine, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Esquire. Cruz is the author of two other novels, Soledad and Let It Rain Coffee. She's the founder and Editor-in-chief of the award winning literary journal, Aster(ix)and an Associate professor at University of Pittsburgh where she teaches in the MFA program. She splits her time between Pittsburgh, New York, and Turin.