One day, during this long ago summer when I was twelve, I went looking for my mother to ask if I could go swimming.

It was late afternoon, dwindling into evening, but that baked-earth smell was still rising on the patio stones. It had been another hot, bright day. All the days that summer were just that sliver too hot, that fraction too bright.

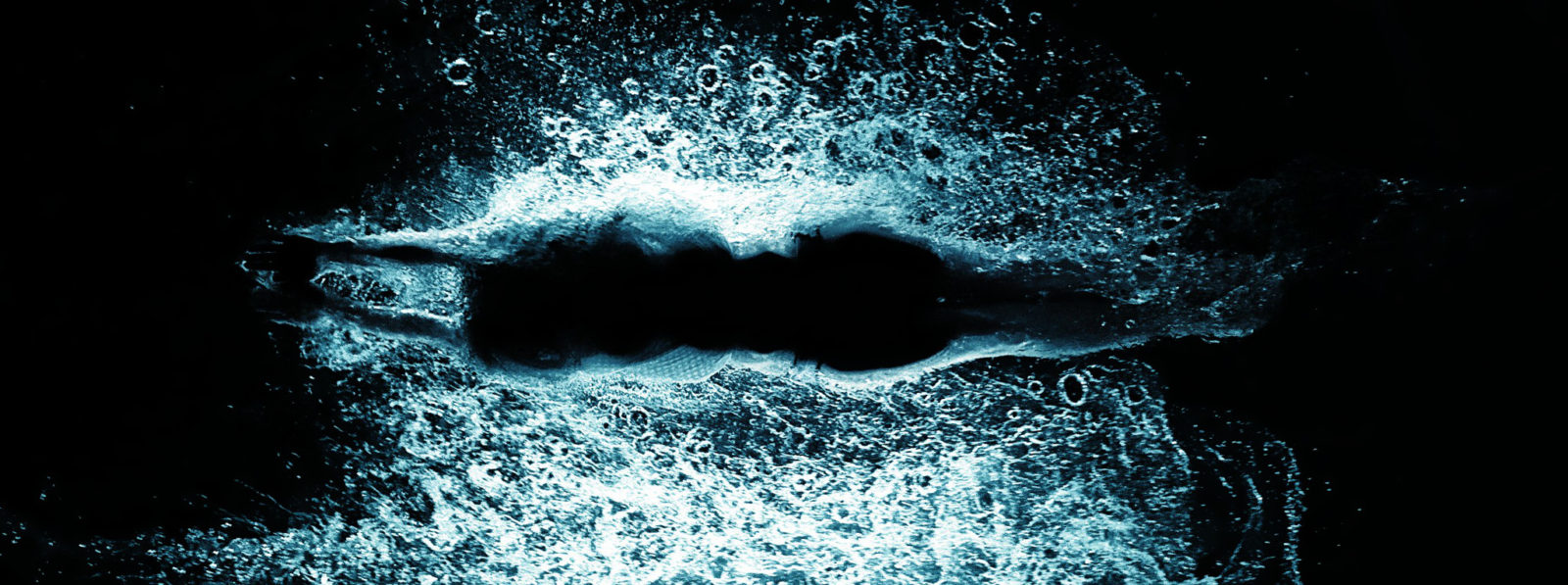

There was a little rock pool on the coarse land that surrounded our summer home, and I was in the habit of going down to the coast to swim inside it. I’d slip into the pool and quickly grow slimy, slick. This wasn’t the salted water of the sea. Left largely undisturbed by the tide, the rock pool felt like the stomach of a water-beast, and like a water- beast it moved thick and slow.

I was allowed to go swimming on the condition I came back within the hour and didn’t swim too close to the pool’s farthest side, which was where the rocks broke and the sea came rushing in whenever the wind ran high.

It took me time to and my mother in our big house, and when I did and her I didn’t recognize her face.

She was a stranger to me, for a few moments, standing at the top of the stairs. Still wearing her nightgown, that old garment whose silken creases she’d once taken the trouble to press smooth.

Though my mother was a tall woman, and though she stood straight, the nightgown reached all the way to the floor.

I wanted to ask why wasn’t she dressed.

I wanted to ask why she was looking out the window. What could she see?

She’d made eggs that morning and they’d been bottomed-black. She’d laughed, seeing the scorch on them, saying she’d been distracted by some bright coloured thing, by some song-bird singing.

Father’s slippery smile all the while showed me bits of burnt stuck to his teeth.

Chewing on the greasy black I’d looked out the patio door to the wall grown thick with roses.

I wanted to be inside the roses.

I knew soft, pink dreams were happening inside their cushion-centred, pillowed hearts.

Do you know about the moon? And about your secret, inside tide?

My mother loved the moon and would talk to me of their kinship, of her endless respect for the big pale planet and its pull.

At night she’d stay out on the balcony, smoking and murmuring.

The things they spoke about—who knew.

Coming in with feet so cold they were sky-blue, little pieces of sky making footfall in the hall.

Tossing her cigarettes like a gaoler might his keys and all the while her nightgown, dragging.

Did you know we all of us have a secret inside tide? You’ll feel yours pull on you, whenever the moon is waning.

This, at least, she was right about.

It drags out particular things, the moon.

Under its magnet rays, certain things come creeping. Little green caterpillars on a leaf.

Never swim when the moon is full and high.

The tidal pool trapped a good-sized body of water that, depending on the moon and its tug, could be very warm or very cool.

The water was sometimes blue, more often green.

Sometimes seaweed straggled through my hair and I returned to the house a mermaid. Vengeful and unappeased, as I knew mermaids to be. Not kindly, fairy tale creatures at all.

Most fairy tales, in fact, have at their heart a lie.

The moon was full but I asked anyway, Can I go swimming?

She looked at me and I saw my question land with a twitch in her eyes. She looked back out the window and the side of her face, mute and still, was maddening to me.

I want to go swimming.

The moon had been bright as the sun, these last few nights, bright enough to guide me.

I’ll be back for dinner, but I want to go.

The cloth stirring and shifting around her hips, her waistline.

Mother, did you hear me? I’m going swimming—I’m going.

That long, long nightgown, its lacy hem snagged on a jagged splinter, so that when she jumped, it was pulled taut behind her.

And then it ripped. It ripped, in fact, very easily, the thin tear winnowing right up her backside, the straps come apart so that it fell from her shoulders.

And so, she was naked when she jumped out the window, and naked when she fell.

The wild thump of my feet on the stairs, running down and down— strange, animal sound.

I had never been allowed to run in the house. I had never heard the noise of it. Running toward Father because I wanted to have told him already that Mother was gone, wanted to begin this life I understood I’d just now, in these last few moments, been forced into living.

I wanted to go and break the heart of this soft man with his burnt teeth. And behind me, at the top of the stairs: cream-coloured. Not quite white. Puddle of cloth.

Pool of moon-coloured light.

Father, the moon has come inside.

Never again would I live in a house that kept its summertime windows open.

No choice but to grow into a woman whose sleep was hot and choked and deep.

A woman who had been a girl who did not pause to grieve her mother. A woman who would find ways to stop herself from dreaming about standing at that window.

Still.

Before the sound of my voice telling Father.

Before the sound of my feet on the stairs.

Crumpled gown beneath my feet and through its cloth the splinter catching my own bare arch and snagging.

A deep cut that left a trail on the stairs and that would open, unpredictably and wetly, for years.

A wound that did the weeping for a mother who died naked on her belly with the moon all the while rising, making her ash silver, ash red.