Humans carved scrapers and points out of stone, and used these to make other necessary tools and hunt for food. Our capacity for abstract thought and reasoning abilities allowed us to gain control over fire, harness its energy in hearths and kilns, and use it to stay warm, light the dark night, and create ceramic vessels. But we also figured out how to use fire as a weapon against one another. Our large-brained power—the gray matter that lets us build shelters and come up with systems of food preservation—is also the stuff that fuels the schemes we hatch as outlets for the rage, mistrust and envy we harbor against those of our own kind.

And now we have Facebook.

I am thinking that maybe one of the distinguishing characteristics of the homo sapien is that we are intellectually able to develop tools before we are emotionally evolved enough to use them wisely.

Don’t get me wrong. There’s a lot I love about Facebook, and it certainly makes every trip to the bathroom more fun. And yet.

For me, right now, the two biggest problems I’m having with Facebook are 1) the ways in which people mistake one’s Facebook wall for an accurate representation of one’s actual, complicated existence, and 2) the ways in which people mistake Facebook posts for productive exchange about difficult, fraught topics. Over and over, I saw myself and others confuse the world of Facebook for vital “IRL” experiences: the experience of getting to know someone, the experience of having a conversation. And such confusion leads to rage, envy and mistrust, which in turn leads to deploying whatever means we have at our disposal—including hitting the “reply” button—as weaponry.

Because as important as our tools and our use of fire are, the need to understand ourselves through our packs–through meaningful interactions and connections with other people—are just as vital to homo sapiens. Sharing resources, caring for one another’s children and making friends quite literally ensures the survival of our species. We are meant to have social lives. And when scientists talk about the necessity of “social networks” for humankind, they are not talking about Facebook.

Another distinguishing characteristic of early humans is that we used our tools not just for functional purposes, but for more esoteric ones: one of the oldest homo sapien skull fossils seems to have been polished and cut for some kind of ceremonial death practice. Almost as soon as we made tools, we used them to make ritual and to make art.

I’m taking a break from Facebook so I can focus on building my one-on-one relationships, virtually and in real life; so that I can pay better attention to the primary social network that is my household family; so that I can participate in my regional community; so that I can free up the space to make more art; so that I can tune in to my desire for rituals other than clicking the “like” button.

What will happen if I miss videos of pandas playing in snow, or the announcement of a benefit dance party in a nearby town, or a link to an interview with Toni Morrison and Angela Davis? What will happen if I don’t get to post the petitions I sign against solitary confinement, or the pictures of my kids playing at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum? We will survive as a species. I can survive it.

I can’t, however, survive without you, the flesh-and-blood connection to you. I want to look at your live, specific face. I want you to look at my live, specific face. #nofilter.

Actually, I want to stop using hash tags, and instead find a direct route to sitting down with you by a fire, with ceramic vessels holding warm liquids in our hands, so that we can hash out all that we need to hash out between us.

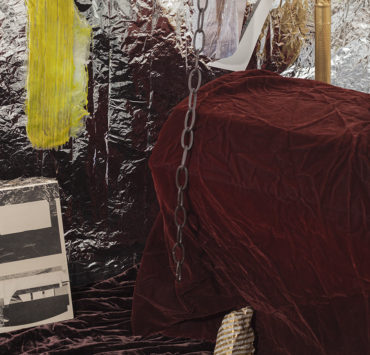

Featured artwork: Damián Ortega, “Moises”, 2007. Found tools and wire

Arielle Greenberg’s newest books are the poetry collection Slice and the creative nonfiction work Locally Made Panties. She is co-author, with Rachel Zucker, of Home/Birth: A Poemic, and co-editor of three anthologies, including the forthcoming Electric Gurlesque, co-edited with Becca Klaver. Arielle writes a column on contemporary poetics for the American Poetry Review, edits the series (K)ink: Writing While Deviant for The Rumpus, and lives in Maine. She teaches in the community and in Oregon State University-Cascades’ MFA.