On October 1st of this year, my cousin Kevin flew from Bogota to Barranquilla, Colombia in order to vote the next day. He posted an early morning Instagram, heavy-lidded and sleep-deprived smile on his face as he boarded his flight.

October 2nd was a big day. Years of negotiations between the FARC (Colombia’s oldest and largest guerrillas) and the government depended on popular ratification—would the people of Colombia vote yes or no to the peace deal negotiated in Havana by President Santos? Did people want an end to the war, even if some of the terms were hard to swallow?

The answer was “no”—50.2% to 49.8% respectively, with a difference of fewer than 54,000 votes. Yet, only 38% of people came out to vote, the other 62% staying away from the polls on a rainy Sunday.

I was in Colombia this August. I picked up the newspaper on the day they ran the full details of the peace accord. Printed out on letter-sized paper, the deal totaled about 250 pages. In newspaper print, even reduced to 20-some pages of 10-point columns, the task still seemed daunting. I soldiered through it on a Sunday afternoon, struggling with both legalese and a Spanish far more formal than the one I speak with friends and family. When I made it to the end, I did my best to look up answers to basic questions I had about the agreement, and mostly found misinformation. Confusion buried in complications surrounded by propaganda.

I considered Kevin, who hadn’t read the agreement in full. Who has the time? he’d argued. He’d gotten his information from the news, from family, and from the political sources he favored.

Surveys cited by the AFP found the “Yes” vote ahead by a 20% margin in late September. Other independent polls released October 1st also indicated that “yes” would win by at least 18 points, a mandate by the people for peace.

When the “no”s won, people around the world expressed shock. How could people vote against peace? is a common headline I encountered on October 3rd. But the bigger question loomed unasked—if 62% of eligible voters stayed home, can it be said that the people voted for “no,” when most people didn’t vote at all?

Political history and multiple civil wars in Colombia point to party extremism—as in, most politically inclined people tend to vote along their party lines with diehard fanaticism (on both the liberal and conservative sides). Yet, along with this extremism, there’s a strong faction embracing indifference, not wanting to be at fault for whatever comes to pass.

Most people blamed the rain. Hurricane Matthew hit Colombia’s Caribbean coast with extreme rains, which kept people indoors. Others point out that “yes” voters simply thought the polling margin too big and their victory secure. A peril of believing in the inevitable, I suppose. Some pointed out that the agreement seems too hard to read, too difficult to understand, and that was enough to scare the unsure away.

The plebiscite had one other factor that contributed to low turnout. The minimum amount of votes necessary for the “yes” to win were 4.5 million. Many campaigns throughout the country urged for abstention, so the basic margins would not be met. Typical bus-in movements failed to manifest, a short voter-registration period meant many people simply forgot to sign up, and the typical bribes and food handouts that characterize Colombian elections were abandoned. Newspapers in Colombia have accused the “no” camp of using abstention as a means of manipulating the vote.

Not voting became a vote in itself. And the war has yet to end.

In 2004, I didn’t vote at all. I was so sure the system was rigged against me. Not voting seemed to be a way of protesting—of saying that I didn’t want to be responsible for whatever old white man ended up in office. As a woman of color coming into adulthood during the post-9/11 Bush era, I coveted the innocence of indifference.

That evening, I remember watching the election results at a bar called the Velvet Melvin in Houston, sitting with my dear friend Renée, watching Bush win again.

As results poured in, the announcers took time to say that voter turnout had been the highest since the 1960s. Over one hundred and twenty million people voted in the 2004 election–about 60% of eligible voters.

Renée had scoffed. How could forty percent of people not vote, she asked? When I told her I hadn’t cast a ballot that day, she stared at me incredulously.In her mind, there’s no way someone who had endured all the trials that come with being a naturalized citizen—wouldn’t vote, right?

Just a little over half of folks voted for Bush. 50.7%, to be exact. Just enough to make you wonder what would have happened if another hundred million people had decided to stand in line and be heard.

This year at a Halloween party, I walked into a strange conversation.

A woman dressed as the Statue of Liberty asked the people on the couch next to her, “Would you rather be stabbed in the gut or punched in the gut?”

“Punched in the gut,” I answered.

“I’d rather stay home,” contributed a man dressed as a gold-plated Abe Lincoln.

Once I realized that they were talking politics, I left the room for another, where I found a dancing Hillary next to someone dressed as sexy Trump.Our political figures are costumes–cartoon characters we mock even as we contemplate which one to elect next week. I saw “bad hombres” and “nasty women” gyrating on the floor, everyone equally content to forget for one night the adult responsibility looming before us.

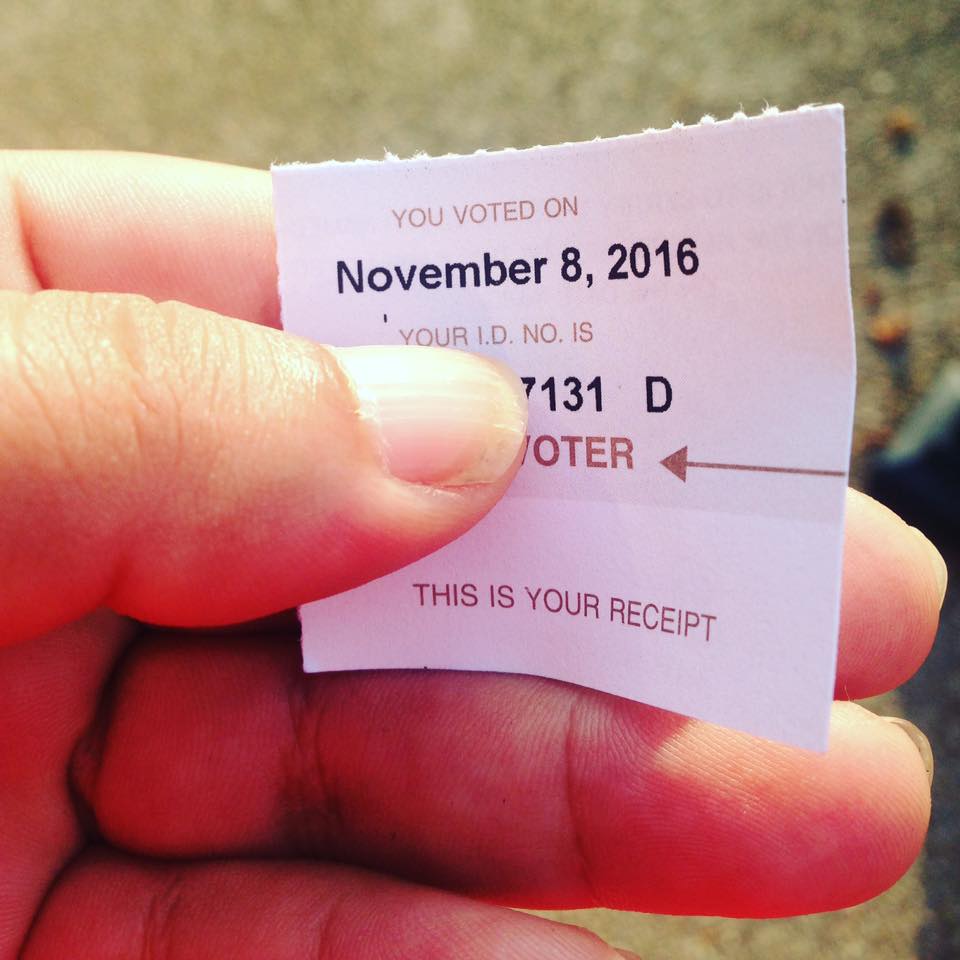

I live in Pennsylvania now, where I’m told my vote matters more than it did in Texas. Canvassers show up to my home in the early evening to ask if I know my polling place. Phone calls interrupt family dinners here with well-meaning surveys and cajoling party-operatives promising a better country for my vote. I voted in my primary. And today I’ll vote in the general election.

We have a chance, as a country, to make a choice today. We can choose our judges, our sheriffs, our city council people, senators, congress people, and yes, our President. I worked hard for the right to vote. I studied, filled out paperwork, and underwent examinations in the name of citizenship. I’m an American. An adult one, at that. So today, let’s all be adults and do what adults do: Vote.

It matters.

Ramírez won the inaugural PEN/Fusion Emerging Writers Prize in 2015 for her nonfiction novella, “Dead Boys” (available as a Kindle single from Little A). A nonfiction writer, storyteller, digital maker, critic and performance poet based in Pittsburgh, she is working on her first full-length book, “The Violence” (forthcoming from Scribner).