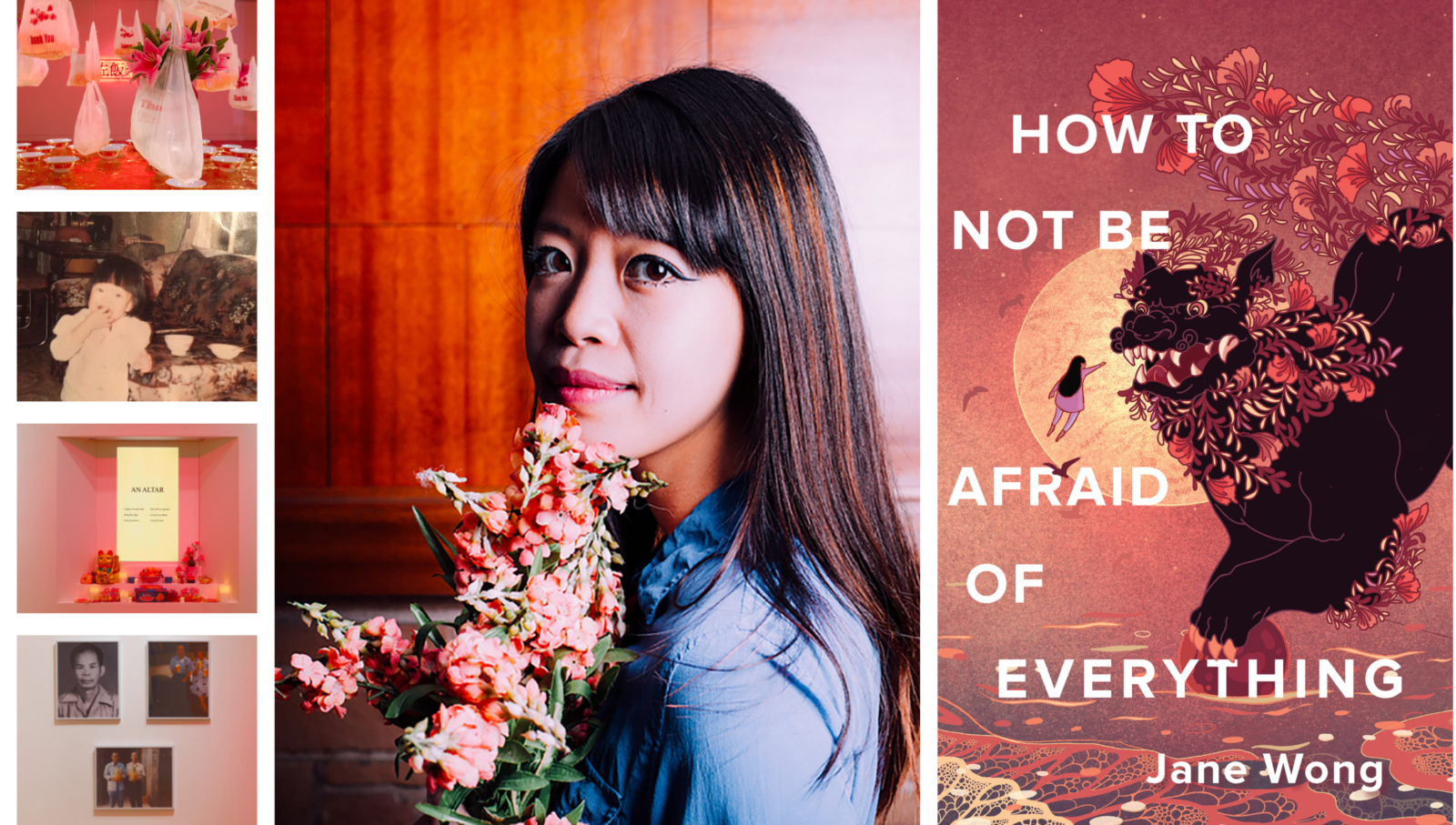

We were honored to have a delicious conversation with Pittsburgh Contemporary Writers’ Series guest Jane Wong, author of How to Not Be Afraid of Everything (available now from Alice James Books). Pitt MFA graduate students Kiera O’Brien and Amanda Tien discuss Wong’s obsession with eggs, the Asian American writer scene, and failure.

Tell us, little girl, are you

Hungry, awake, astonished enough?

— from “After Preparing the Altar, The Ghosts Feast Feverishly” by Jane Wong

EMBRACE THE MESS

Kiera O’Brien: During your visit to Pitt, you encouraged us aspiring writers to get messy! I struggle with this, even when I want to embrace it. I recently read a beautiful exchange on Instagram; a follower asked Ocean Vuong, “What inspired you to start writing?” and his response was simple: “I learned that I was very comfortable with failure, which is a constant part of writing.”

Similarly, you’ve spoken frequently about your willingness, desire even, to engage with the possibilities of failure when you write. How do you engage with failure and mess as part of your poetics?

Jane Wong: I love this question and I will admit, I struggle with getting messy too. I have recently started to learn how to throw clay, which is incredibly messy; the clay gets everywhere (your clothes, hair, eyes). It has taken me a long time to embrace the mess and, to do so, I have to return to my younger self.

Kids are messy. Kids smear sauce all over their faces. Kids put dirt in their mouths because they want to know what it tastes like. As a poet, I want to return to that baby self, to baby Jane. I want to learn how to undo order, how to allow failure back into my life. I love how, when writing, a poem can surprise me. And that surprise often arises out of its failure—which can sometimes spark a volta. I don’t want to know where I’m going when I write; I want to be as bewildered as possible, blinking away clay drippings from my eyelashes.

Amanda Jo Tien: I wanted to say that you’re an all around badass. I appreciate how hard it must’ve been for you and Diana Khoi Nguyen, and other Asian American artists, to be coming up as writers in the MFA and beyond without support systems or institutions that understood your work. A lot has changed in the last two decades. I’m grateful for leaders like you in this space, that people created organizations like the Asian American Writers’ Workshop.

JW: I love the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. When I was a kid, I remember I asked my mom to take me into New York City for a day just so I could literally go in there and talk to people. I carried those flyers around with me all the time. And now there’s more spaces, like the Asian American Literary Review and Kundiman.

AJT: Yes! I went to Kundiman’s launch of Tiana Nobile’s collection Cleave, and it blew my mind. It tackled this area of cross-national, cross-race adoption that I hadn’t read in poetry before. It was intimate, sharp, and enlightening.

JW: Exactly. Every time I read work by Asian American students, I ask myself, “Could I teach this in a few years?” And the answer is yes. To be excited…it makes me feel very lucky. I actually had Tiana come into my Asian American Womxn Writers class this past year and my students, many of which identify as Asian American adoptees, were deeply moved by her reading.

POEM AS PLANT

KO: I was lucky enough to see your incredible installation, After Preparing the Altar, The Ghosts Feast Feverishly, at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle in 2019. It changed my writing-making life; I remember thinking “Wow, this is an option?” I had never seen a poet present a poem as installation art. It made me feel less alone, less weird, in pursuing my own transdisciplinary work.

It was thrilling to encounter the same poems I saw in the installation on the page in How to Not Be Afraid of Everything. What’s the process like when you are working on a gallery show and bringing a poem to life as part of a broader art piece, rather than, say, a published collection?

AJT: Yes, how do you balance exploring multiple curiosities and projects at once?

JW: When I think about a poem, I think about the legs it has outside of that one space on paper.

I consider poems almost like self-propagating plants—like there’s another sprout that comes off of it right that is still part of the mother plant. And for me, that’s how I move through different art pieces, trying to follow those organic threads of curiosity. I try to allow myself to be as wild as possible. The poem, off the page, has another life!

KO: What nourishes you and your creative explorations? Literally, do you mind sharing what you like to eat while you are writing?

JW: I love eating snacks! I love clementines, chips, salted almonds, and seaweed. Anything that will fit into a small bowl. At Hedgebrook, a residency for women-identified writers where I spent the last few months, they have this snack wall that was my literal dream space. There were so many jars full of snacks! I love anything savory. Sadly, I don’t have a sweet tooth, but I do love any fruit.

Sleep nourishes my poems; I love writing in bed. Something roasting in the oven also nourishes my poems… I love leaving something to roast and having that 45 minute window to write/dream up something. Most of all, conversations with fellow writers and artists nourish my poems and I am always sparked by my friends—especially Michelle Penaloza, Diana Khoi Nguyen, and Anastacia Renee.

RETURNING TO HAUNTS

I have this strange feeling.

I’ve written about this before. I’ve always been writing to you, even before I was

born.

—from “When You Died” by Jane Wong

KO: Rituals of repetition and return seem integral to the work you are doing in How to Not Be Afraid of Everything, such as in the beautiful, haunting “When You Died.” What part does ritual—and this cyclical sense of returning to the same images, words, phrases beyond linear time—play in your process?

JW: I’m a huge fan of returning to your obsessions. I hate it when people are like, “Well, hasn’t that been written about before,” or “Didn’t you just write about this,” or “I’m worried, you wrote about your mother again.” Like, well, yeah, I’m obsessed with my mother. What’s wrong with returning to your obsessions? Isn’t that what makes you who you are?

So, whenever people use terms like “repetition,” I consider it a ritual, a re-conjuring up of what still clings to you. For example, I did a reading a few weeks ago and some students said, “Jane, what’s up with all these eggs? There are A LOT of eggs in your book.” And I was like, yeah, I’m obsessed with them.

KO: Why do you return to the egg?

JW: I think the egg for me is a symbol. What it means for my mom to have grown up in a space of hunger. For her birthdays, an egg was so lucky to have. That protein. A treat. And then here I am, growing up in a restaurant, bored and terrible. I remember once I took an egg and threw it in the parking lot, and my mother was furious. I thought she’d be mad because I made a mess, but she said, “How could you have done that? How could you have just thrown an egg?” In other words, how could I have wasted such precious protein? So yeah, I’m obsessed with eggs and I am unapologetic about repeating it, constantly circling around that yolk.

DISSONANCE OF THE SELF

My mother has been told, repeatedly: “You can’t walk here”

Here is a white stone, a white fence, a white sea gull, a white jug of milk, a white candle, a white duvet, a white piano, a white bar of soap to wash your mouth out

Sometimes I dream in Cantonese and I have no idea what is being said

—from “Everything” by Jane Wong

AJT: The egg is the egg, but it’s also so much more than that. It’s inheritance, gratitude, filial piety…those are all themes that I feel come up often for Asian American artists. In that community, writing is something that is often hard to justify, especially to guardians. Even if it is something that fuels your work, it’s complicated. There’s a lot of power at play—with gender, nationality, generation, and more–that is difficult to navigate.

JW: Yes… there’s a deep dissonance between my child self and the institution. I am constantly aware that the labor of my art is so different than the labor of my mother, who is a USPS postal clerk.. Upward mobility is so complicated. The very fact that I get to pursue what I’m passionate about is complex for me– like, did my mom have that same opportunity? No.

KO: Where does that dissonance leave you? How do you navigate it?

JW: I struggle a lot with this question. It feels like I’m always losing my childhood self the longer I stay in the institution. The institution does not want Baby Jane, or even Jane. It wants Dr. Wong. As someone who is a first-gen college graduate, I didn’t know all these rules. I didn’t know how to behave, how to send emails, what the boundaries would be for me.

I am still struggling with this frustration. The institution has granted me so many opportunities, so many privileges. When I got tenure, people congratulated me. But I was furious. I was furious I had to jump through all these hoops to prove myself worthy. Why would I ever need to prove my worth? The institution wants to lead foremost with gratitude, when I want to lead with rage.

As a woman of color in the academy, I do more labor than my white colleagues. But then I have guilt that my mother is laboring more than me. And I ask myself, “Was it worth it? Is it worth it?”

In the fight, you have to remember to rest.

Jane Wong is the author of How to Not Be Afraid of Everything from Alice James Books (2021) and Overpour from Action Books (2016). Her debut memoir, Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City, is forthcoming from Tin House in 2023.

She holds an M.F.A. in Poetry from the University of Iowa and a Ph.D. in English from the University of Washington and is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Western Washington University. Her poems can be found in places such as Best American Nonrequired Reading 2019, Best American Poetry 2015, American Poetry Review, POETRY, AGNI, The Kenyon Review, New England Review, and others. Her essays have appeared in places such as McSweeney’s, Black Warrior Review, Ecotone, The Common, The Georgia Review, Shenandoah, and This is the Place: Women Writing About Home.

Kiera O’Brien is a transdisciplinary artist and writer from Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her work has appeared in Tupelo Quarterly, Foothill Journal, Dead Skunk Magazine, and elsewhere. A frequent collaborator with the international performance collective Mammalian Diving Reflex, she is currently pursuing an MFA in Poetry at the University of Pittsburgh.

Amanda Tien is a writer, artist, and marketing strategist, currently working on her first novel while pursuing an MFA in Fiction at the University of Pittsburgh. Her work has been published in Public Books, Poets.org, Call Me [Brackets], Columbia College Today, and The Punished Backlog. She is the Managing Editor for transnational feminist literary journal Aster(ix). Her work can be viewed at www.amandatien.com

Credit for all photos of Jane Wong’s exhibition at the Frye Museum: Jueqian Fang.

This piece includes both edited transcripts from Jane Wong’s visit with the graduate MFA course as an Artist-in-Residence at the Pittsburgh Contemporary Writers Series, and interview questions with Kiera O’Brien and Amanda Tien.