Natalie M. Léger: I would like to open this interview by thanking you for this memoir. It is a gripping portrait of our fragility as human beings. It beautifully captures the toll that chaos (familial and socio-political) reeks on our individual sensibilities and on our personal conduct towards others and ourselves. So much of this memoir is about healing, the journey towards individual and national healing, and the impossibility of both. What are your thoughts on how a person might exist in stillness, in the calm after the storm when the “sky [is no longer] the color of chaos” and is there a reprieve from turmoil? Is there ever a reprieve, for you now, years removed from your childhood and adolescence in PAP, and more abstractly for anyone whose early beginnings were equally tumultuous?

M.J. Fièvre: I’m still haunted. I struggle with the question: How much of the anxiety I still experience is due to my past, and how much of it is a personality flaw—the innate inability to exorcise difficult memories? It’s been fourteen years since I’ve left Haiti, and my senses remain on high alert: I’m aware of the possibility of danger at every corner, of all the worst-case scenarios. I also find it difficult to trust people; I question motivations and cannot escape my own fragility, my own insecurities. I’m working on an essay titled “The Way We Cope,” about my family’s idiosyncrasies and obsessions, which are surely a response to trauma. Even when there’s stillness—or should I say particularly when there’s stillness—terror is always ready, always waiting to seize us unawares. In some families, trauma survivors turn to smoking, drinking, and/or drugs. In my family, the compulsive spending and disordered eating can get ugly, but nothing is more terrorizing than (almost) losing a member of the tribe to a religious sect.

You become a part of where you are from, and your homeland becomes a part of you, so that you can never truly escape, even when you leave these familiar grounds. This is particularly true for a place like Haiti, where the sky is always the color of chaos. I’m miles away and yet I’m often kept awake at the thought of a kidnapping, at the thought of the earthquake quietly sleeping beneath Port-au-Prince, waiting to rise up one fine ordinary day and destroy everyone I love. I’m miles away, and yet I experience the fear that anyone left alive after the ground has stopped shaking and the walls have fallen down will then be prey to looting and pillage, to starvation, dehydration and disease. I worry about the next coup, the next bloodshed.

NML: It’s interesting how your response moved from your familial experience of chaos to a national experience. I find this transition compelling in large part because it positions the chaos stemming from familial relations as seeping into the day-to-day operations of the Haitian state. This leads me to my next question regarding how Haiti is imagined abroad through chaos alone. As a Haitian-American and as a literary scholar, who studies how narratives are used to further imperial exploitation, I am keenly invested in Haiti’s representation in the U.S. cultural imaginary in particular. I have noticed that there is a way in which artists from the Caribbean (and Haiti, specifically) are made to express not simply their personal experiences or a fictive world in their works but the world of the entire nation/region. Nuance is forfeited for a general confirmation of the idea already held of the nation and/or region. And, as a result of that, fictional narratives can border on the anthropological, serving as a window into the “unknown.” The press release for your memoir does this via its framing of your piece in order to solicit readership. I think here of these two paragraphs:

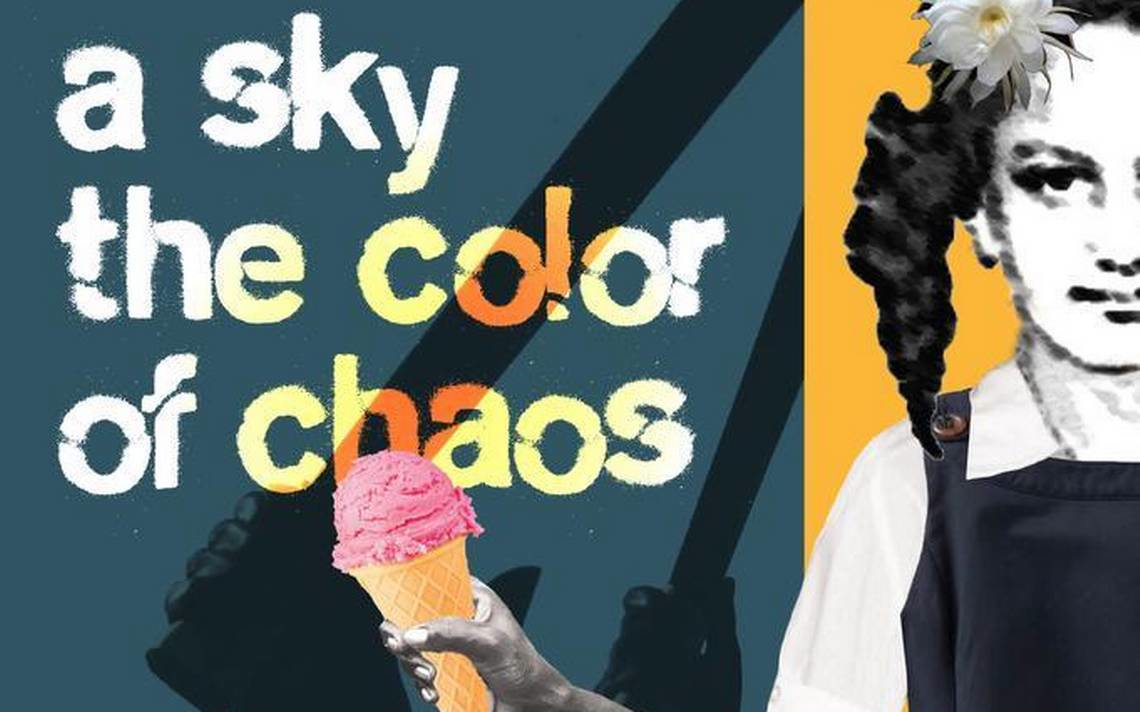

A Sky the Color of Chaos chronicles M.J.’s childhood during the turbulent rise and fall of Haiti’s President-Priest, Jean-Betrand Aristide—a time of nightly shootings, home invasions, robberies, and even the burning of former regime members in neighborhood streets. During the late 1980s and 90s, Haiti’s government changed forms eight times before M.J. reached adulthood; the Haitian people endured fraudulent elections, three military coups, a crippling embargo, and a United Nations occupation.

In A Sky the Color of Chaos the social and political upheaval merely serves as the background for the more personal drama playing out inside M.J.’s own home. …

Does framing like this concern you as a Haitian writer now publishing in the U.S.? More specifically, does it concern you that your fiction/nonfiction, no matter its content, will be filtered through the conventional idea that is shared about Haiti in the U.S. (Haiti as poverty stricken, chaotic, corrupt, and unable to self-govern)? Relatedly, against the popular idea of Haiti held in the U.S., what is your particular understanding of Haiti? What does it mean to you to be Haitian during the formative years detailed in your memoir and now? And how has your personal understanding of Haiti and your cultural identity shaped your literary production, past and present?

MJF: I’ll start with a mea culpa. I think I did my own framing when courting agents and publishers. I did put the accent on the violence that permeated A Sky the Color of Chaos—because I wanted to sell the book! I did later become concerned with that framing. After the book was published, I realized that audiences at my readings were more interested in passages that conveyed the traditional idea of Haiti as an unbearably violent place. My most popular passages include the burning of the supposed macoute and the shooting during the embargo protest. When I read these passages, more books are sold, yes, because there seems to be specific stories people want to hear. I make a conscious effort, however, to also share excerpts that focus on the under appreciated aspects of Haiti, navigating between the audience’s expectations and the realities they might not be aware of. I am interested in expressing concerns about poverty, chaos, corruption, and so on, but I try not to situate those concepts through a fixed discourse. I try to avoid the clichés.

My understanding of Haiti comes in bursts, during my writing, when I’m not concerned whatsoever with expectations. In fact, when I’m writing, I’m not even concerned with facts. I’m concerned with the emotional truth. Historical details and memories can be distorted and interpreted differently. The greater truth cannot. I don’t let stories people created about my country shape my understanding and the rendering of my own experience. I wonder, however, aren’t all worlds constructed worlds, and all identities constructed identities? My Haiti is very different from the Haiti of a woman raised in the slums. My Haiti is very different from the Haiti of a police officer supporting a family of seven on a meager salary. In other words, here’s my understanding of Haiti: she wears many faces, depending on the identity of the individual looking at her, depending also on the time period under consideration. “Ayiti, se tè glise.”[1] The country is in a perpetual state of transition—always brilliant, undulating and mysterious.

I wonder: Am I a “real Haitian” when my experience of Haiti was drastically different from that of 80% of the population? I spoke French at home and at school, when French remains a foreign language for most people in Port-au-Prince. (In fact, my Kreyòl has been accused so often of not being the “real Kreyòl” that I purposefully make it more “rèk”[2] when working as a court interpreter.) As a teenager, I favored The New Kids of the Block, and later rock music (Oh, The Cranberries!), when most people listened to local artists. Is being Haitian about being born in Haiti, about embracing Haitian culture and customs, about upholding Haitian values? If it is the case, am I less Haitian because I promote gay rights and feminism, when Haiti is a very patriarchal society with traditional values? Am I less Haitian for choosing Apple Jacks over banana porridge for breakfast? Now that I live in the United States, here are some more questions for debate: At what point (if ever) do you stop being Haitian? What claims to “haïtianité” do you have when you were born overseas from Haitian parents but have never visited Haiti? As I explore these questions in my writing about an experience that is both collective and singular, I do not shy away from the inevitable failures I encounter in my search for truth. In fact, I often abandon the search altogether and instead allow readers to dwell in peaceful, resigned unknowing. “Haitian” is a term that’s utterly expansive in its breadth and experience. “Haitian” means many different things to many different people. When you’re Haitian, you know it in your guts. The act of writing forces me to relearn my own identity. I want to believe that this identity, in turn, enriches my writing. Haitian lore has found its way in the YA novels I published while I still lived in Haiti. The preoccupations of my characters are Haitian. I might write in English these days, but I still think in a mix of French and Kreyòl.

NML: As I read your memoir, I was struck by your adolescent sensitivity to the class and colorist distinctions within Haitian society. Did your experience of being called “tifi wouj” (red girl) by others outside of your family influence how you saw yourself, your family, and your social milieu in relation to the larger population in PAP?

MJF: The awareness of my privilege was cumulative, so being called “tifi wouj” was in no way a life-changing, ah-ha moment. My perceived otherness (not subtle and not harmless, bur rather disturbing and uncomfortable) in Thomassin[3] was again a confirmation that Haiti fails to allow and celebrate the intricate identities that make up her people. This can be dangerous. Whenever there’s “otherness” (the kind that is not embraced, but rather creates distrust and alienation) there’s also the threat of violence just beneath the surface of everyday life. Something dark is lurking in the background, threatening to turn to nightmare at any moment. In Haiti, the marginalized has never had a voice. Not really. A day will come, however, when they will demand the space of the center and beseech those already there (the “others”) to accept them as equals.

I could have seen the “otherness” (and the attributed/perceived “superiority”) of my social milieu with defiant pride but it filled me instead with an intimate sadness and with the helplessness that comes with the inability to control how I am portrayed and the fact that I must continually either overlook or submit to the various discrepancies between Haitian identities. I learned early on to separate the outside world from my inside world—to see myself from an outsider’s point of view. I learned to make the effort to understand life from a position of otherness. This contributed to making me a decent writer, I think.

NML: Your response to the previous question and this question draws attention to the constructed nature of narratives, be they those produced by foreign others or those Haitian nationals produce of themselves; and as such, both highlight the contradictory space of accommodation and invention that individuals navigate when seeking to express their distinct realities. That is, even as the individual (say the writer, for instance) creates to express his/her Haitian-ness, the idea of Haiti that others have (those who are Haitian and those who are not) will nonetheless influence the work that is created. It is clear that you strive to prioritize your preferred narrative of Haiti and yourself. This is evident by how you balance what passages you read during your readings and by your clear desire to broaden haïtianité. Do you find that there is a distinct and fixed understanding of haïtianité that exists? Do you see your memoir as set against this idea?

MJF: There seems to be two prevalent (and extreme) narratives when it comes to “haïtianité”—one is of denial, the other one of doom. The narrative of denial will focus on the unrelenting beauty that comes with being Haitian: it will speak of the hard work and limitless creativity of Haiti’s people, of our perseverance and courage, of our pride, of our deep connection to our ancestors; it will be relentless in its reminder that Haiti was the first independent black nation, that Haitians are survivors. This narrative doesn’t deny our flaws per se, but there’s a tendency to simply laugh them off: Nou lèd, men nou la (“We are ugly, but we’re here”)—and we’re the cream of the crop! In the other narrative, “haïtianité” means poor, corrupt, uneducated, and irremediably broken. This second narrative robs us, Haitians, of our dignity, because it only makes us as good as our worst shortcomings. I prefer more balanced narratives—“middle ground” stories that show the different facets of Haiti: the good and the bad. I want to believe that A Sky the Color of Chaos is in the middle ground.

NML: One of the most riveting moments in your memoir is the knife episode. It reveals how violence can be attractive to victims of violence because it can afford a sense of control and stability in an otherwise chaotic moment. What was it like for you to return to this moment to write this incident and to detail your emotions?

MJF: Internalized violence is like a predator on the lookout. You’re simply going about your day—driving, sleeping, showering, or shopping—and then suddenly, improbably, amazingly, this inner beast shows its ugly head and the entire world starts falling apart. Now, at least, I know who I am. I’ve learned to handle the roots and consequences of my pain and poor decisions. As an adolescent, however, uncertainty matched my every step. I couldn’t find balance as I wondered how much violence translated the normal mood swings of a teenage girl, and how much violence was in fact abnormal/inadmissible. When I think about how I almost used that knife, I’m choked, once again, by the powerlessness that can come in the face of internal demons. My inner violence terrified me then; now it fills me with irreconcilable sorrow at the thought of this young girl and the violence that continually took on a horrifying solidity around her despite her best efforts to keep herself insulated from that violence. I’m sorry for this girl who burned from the inside with rage, fear, yearning, self-doubt, and ever-aching love. But pity seems like a condescending emotion, a lazy feeling. I try to feel compassion and sympathy instead for my younger self.

NML: Your memoir seems to make an explicit connection between your early aspiration to be a doctor and your choice to be a writer. It seems to me that, your desire to be a doctor is firmly tied to your determination to escape the unrest you experienced in your familial home and in PAP. And this desire is implicitly tied to your love of writing and the restorative power (I think you afford) the written word. Is writing restorative for you? Do you think your adolescent desire to be a doctor was precisely because of the salve that writing (and reading) was for you?

MJF: As a teenager exploring career options, I visited the Hôpital Général in Port-au-Prince several times. Once I found my uncle, an orthopedist, about to perform a reduction: he was going to realign an old man’s shoulder joint. The man, a mason, was in dire pain from a ladder fall—tears streamed down his cheeks, and his hands shook. As my uncle forced the bone back into place, the man let out a wail. My heart jumped. I’m sure the manje kuit vendors[4] heard him three blocks down the street. But then: Silence. Relief. Sometimes, in order to overcome pain, we need even more pain. That day, I gained a new appreciation for both orthopedics and writing, which both bring healing that requires a kind of suffering. While bone doctors deal with tangible pain, writers can explore what mental anguish looks from the inside at its most disturbing. Just like a medical reduction, there is violence to writing. Our writing costs something of ourselves and honesty is always violent, to ourselves and too often to those around us.

My desire to be a doctor also had to do with finding purpose through healing: I could show great compassion and strength for another person, all while fixing him/her. Writing gives me purpose: It puts me in a space where I’m allowed to be more than a victim with a family history marred by trauma, confronted with the task of constructing an identity and a coherent story in a world made of turmoil: I can be fully human and show compassion for what goes on inside other sufferers’ heads—the voice of the trauma, the frustrations, the shortcomings. In both cases, there’s hope: the conviction that the patient and the writer will eventually break free from the pain. In both cases, the mind is keen and curious, forcing the youthful naiveté to fall away. In both cases, the healer is changed, for better and for worse, irreparably. In both cases, it’s often necessary to pause—to gather up questions and recharge—and realize that as long as we keep our passion and love, we can rekindle our hope and battle on.

NML: In an interview for Aster(ix) Nelly Rosario states, “Men write with answers, women with questions” (http://asterixjournal.com/nelly-rosario-pushcart-nominee/). I would like your take on this statement because your memoir is so full of questions versus answers. The reader is satiated by both the beauty of your prose and its emotive power but intrigued as well by what is not said. As I completed your piece, I could not help but to wonder: what becomes of your relationship with your father? What becomes of your sister, your mother, Estelle, Felicie and Felix? How often did you return to Haiti following your initial departure? More then these questions, I am interested here on your thoughts on the gendered nuances of artistic production that Rosario points to; but please feel free to answer the other questions as well.

MJF: I still write in a diary, only I call it a “journal” nowadays in order to sound more adult. My journal is titled “My life in questions” and every single page is covered with questions—about health and veganism, relationships, spirituality, gender identity, sexual identity, racial identity, politics. I think in questions because I don’t have answers, and I don’t trust anyone who pretends to have answers. I recently turned 35 and I’m still trying to figure out where I belong in this complex universe.

My writing is not an act of conveyance. I do not intend or attempt to deliver a truth to a reader. I expect every reader to experience my story differently—based on his/her own journey—because my writing doesn’t aim at creating a truth outside of the reader’s own life. I don’t know that this approach, which does ask more questions than it answers, is necessarily a female one. Maybe it is.

NML: What was it like to write in English, to communicate a childhood and adolescence you experienced in French and Kreyòl, into another language?

MJF: Language inevitably shifts understanding, performance, and intention. When I think in French, I can hear my mother’s contrite voice: “Le linge sale se lave en famille” (Do not air out your dirty laundry). When I think in Kreyòl, I am overwhelmed with shame: “Byen ou twò byen” (What right do you have to talk about sadness and loss when you come from privilege?) I’ve never grown up with anyone, or indeed ever even lived with anyone, who spoke English as a first or only language. English was freeing: no judgment, no accusations. Here was a lovely language employed in the service of unlovely content that at once married violence and tenderness. Writing in English also forced me to think about the diversity of my audience. I started A Sky the Color of Chaos as a graduate student in the Creative Writing program at Florida International University. My writing workshops included students from different countries and different parts of the U.S., different ethnicities, different religions, different sexual and gender identities. When your audience is so diverse, you learn to think outside the box. You learn not to be boring. You learn to hone your craft and create stories and poems that feel rich, vibrant, and utterly necessary. All in English. I examine each of my stories precisely – “like a surgeon making perfect cuts into flesh, each thought curated before being laid out on the page” (to quote Nicole Capó).

NML: Could you speak about your process for writing and for completing this memoir?

MJF: At first, A Sky the Color of Chaos was a collection of stand-alone pieces. My process is always the same: I start with a stream of consciousness, which lends my first draft a kind of delusional quality, as though the story’s been crafted through blinding sweats and waking dreams. Without expectations or demands, I let the story flow out, making no choices about the details. Every so often I employ the second person to address an unnamed character or (in the case of the memoir) my younger self. I free-write about lies and betrayals, heartache and loss, because only through darkness do we learn about the light. I allow myself to go back to some very dark moments, leading myself ultimately to a new dawn and rebirth. During revision, I create a story map and worry about the arc. I’m also ruthless, hunting down sentimentality. I try to create balance between violence and tenderness, between facts (which can be too dry) and perception (which can be too self-indulgent). I add poetry to my sentences. I fact-check.

NML: Who are the authors that have most influenced you and writers that you continually turn to for inspiration?

MJF: Everything I read teaches me about craft—what works, what doesn’t work—so it’s difficult to pinpoint one or two writers who have really influenced me. I can tell you about writers I love: Gary Victor, Edwidge Danticat, Jean-Paul Sartre, Anton Chekhov, Dean Koontz, Denise Duhamel, John Dufresne. I like short stories better than longer works, so I mostly read literary magazines when looking for inspiration. I love Aster(ix), of course! Pank Magazine is one of my favorites. Ploughshares. Sliver of Stone! I’m a big fan of manga, comics (The Flash!), and graphic novels.

NML: What are you working on now?

MJF: I recently wrote a play, Shadows of Hialeah, for Poetry Press Week during the O, Miami Festival. An adaptation of the play (No Pill for Loverhorn) will be performed at the Miami MicroTheather in June 2016 to celebrate LGBTIQ month. I’m also working on a collection of short stories in French, and on a fantasy novel in English.

[1] Haiti is slippery ground.

[2] Indigenous, raw, “straight up” Creole

[3] M.J.’s childhood neighborhood

[4] Literally “cooked food” vendors

M.J.Fièvre is a poet, essayist, short story writer, translator and the author of numerous French-language novels. Her most recent work is the English-language memoir, A Sky the Color of Chaos, chronicling her upbringing in the turbulent Haitian ’80s and ’90s. An avid blogger and currently a professor at Miami-Dade College.

Image Credits: Beatingwindward

Natalie M. Léger is an Assistant Professor of English at Queens College, CUNY. She completed a PhD in English Literature at Cornell University in the field of Caribbean and postcolonial literature and a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship at Tufts University. Her research explores coloniality and anti-blackness in the Caribbean literary imaginary. Her current book project, Envision Otherwise: Haiti and the Decolonial Imaginary, concerns the theoretical and artistic importance of Haiti and the Haitian Revolution to to radical decolonial thought in the Caribbean.