I come from a place in which I was taught that you don’t meet violence with violence and that misconduct and mistakes, particularly when people own up to them, should be met with constructive dialogue that lead to justice and redemption. This is a conversation I have been immersed in since last year when Harvard revoked Michelle Jones’s admission. Jones had served twenty years in an Indiana prison for killing her 4-year-old child. While in prison Jones not only rehabilitated but became a leading scholar and researcher. Harvard’s decision made many of us professors and students upset. Why is Jones being punished all over again? When does a person end being punished and allowed a chance to prove themselves? I am interested in thinking more about the ways in which we, as a society, and we, as academics, deal with condemnation and punishment. More importantly, I am interested in thinking more about the unequal ways in which scholars of color seem to suffer longer sentences for their misconducts and crimes while white men (surprise, surprise) continue to walk and get away with hurting others.

Many of the things Junot Díaz is being accused of, namely being an asshole, are the lived everyday life experiences of those of us on the tenure track as well as graduate students, more so if you are a woman of color. I open my own book with a violent experience I had my first week in graduate school at Michigan where a white man, a professor, referred to my country of birth as the source of “cheap whores.” During my years as a graduate student at Michigan, I had other white professors question my abilities, my research, and my place in the academy. After laboring for six months on a dissertation chapter, one of the professors I asked for feedback asked me if I had “problems writing because this is pretty bad.” Another told me that I was never going to get a job because “I was too close to the subject” and it was clearly not possible for me to write a good book. Later, when I graduated and opted to have a child, a senior female professor told me that “the pregnancy must have affected my brain because I was writing pretty horribly.” To those examples, I can add the violent ones I have lived on the tenure track that ranged from racist and sexist micro-aggression to harassment. The perpetrators were not always men. They were not always white. If I thought calling them out on the twitter world would end the structural violence in academia, I would have. But we all know that is not how it will end. While it is courageous to speak up against a person, the real labor is in changing the structures, and that labor includes thinking together about justice and redemption.

As a Dominican scholar, I am supposed to make a statement about Junot Díaz. For now I will offer suggestions for those who want to have a productive conversation about the structural violence in academia and the art world that allows on the one hand for assholian/bullying behavior to be, not only acceptable, but expected, and on the other for a dialogue about sexual violence that has dangerously begun to conflate micro-aggression and machismo with rape in the same breath. If you are a victim of rape, I assure you, it is not fun to hear someone equate a senior faculty yelling at you at an academic panel (otherwise known as a common MLA scene), with being drugged and raped at a party or with being molested as a child. While all of these violent actions are condemnable, we need to nuance the conversation and dislodge the words we are using, in order to respect the experiences of victims and address the ways in which structures operate in different spaces (academia, the art, the street, family, government) to inflict different forms of violence of people. So my initial thoughts are responding to the question: How to teach Junot Diaz’s work now?

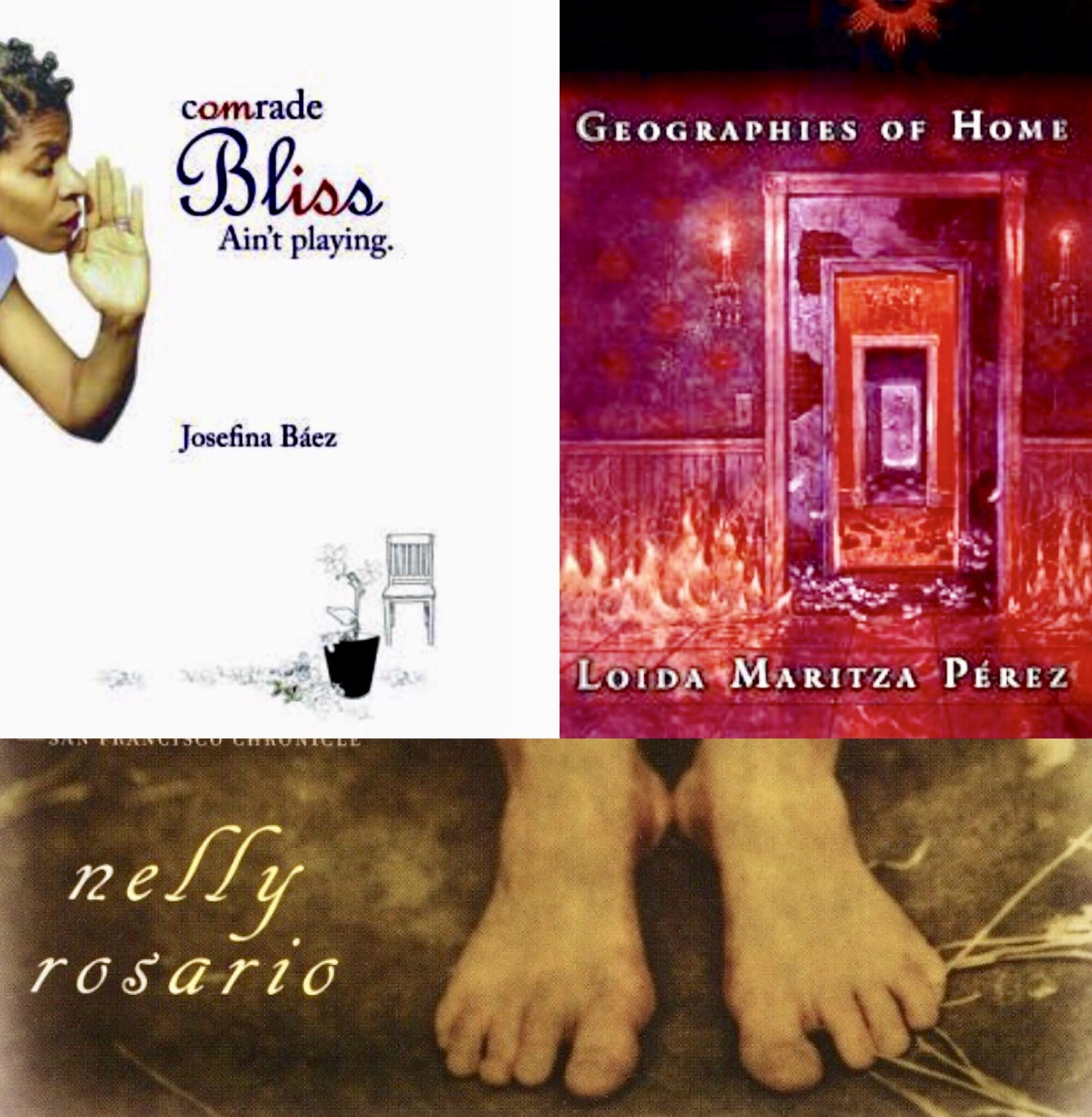

To that I ask how have you been teaching his work until now? And more importantly, who else are you teaching? I find that in many syllabi Díaz is the representative of Latinx, if not minority, literature. That’s it. For those of us who teach Latinx literature, Junot then comes to occupy the Dominican spot. I imagine losing him would pose a problem if one knows no other Dominican author. There are many options there. While I don’t often teach Díaz’s work mainly because my own teaching and research practices lead me to teaching, in justice, lesser known authors, when I do teach his or anyone’s work I lead my students to ask difficult questions and to engage with the text critically. I do not agree with the mentality of only teaching people you like as human beings, that is a reductionist, and close-minded way to teach. It also means you are only teaching your friends. Both practices are detrimental to students. So for those who want to continue teaching Díaz (the way we teach Sarmiento or Penson or so many historical asshole men), I would invite you to continue to engage your students critically but more importantly to not make Junot Díaz the resident Dominican in your syllabus. He is the only Dominican-American male author. Why not live a little and read Josefina Baez, Nelly Rosario, Angie Cruz, Rita Indiana, Loida Maritza Perez, Rhina Espaillat?

Lorgia García-Peña is a Professor of Latinx Studies at Tufts University, the co-founder of Freedom University Georgia, and the author of three books: Translating Blackness (2022), Community as Rebellion (2022) and The Borders of Dominicanidad (Duke 2016). She is the co-editor of the Texas University Press series, Latinx: the Future is now and the co-director of Archives of Justice. She writes and teaches in English and Spanish about the intersections of blackness, colonialism and migration, centering Black Latinx lives.