Apá is the cashier at the store. His face stares back at me.

He rings up bean cans and a soft thud echoes each time he sets one down. He makes sure they’re not stacked so that they won’t fall. His shriveled fingers tap the worn keyboard, nails wrinkled and bitten.

Apá looks up at me, a slight tilt to his lips that itches my heart. I want to tear it out of my chest and scratch it raw.

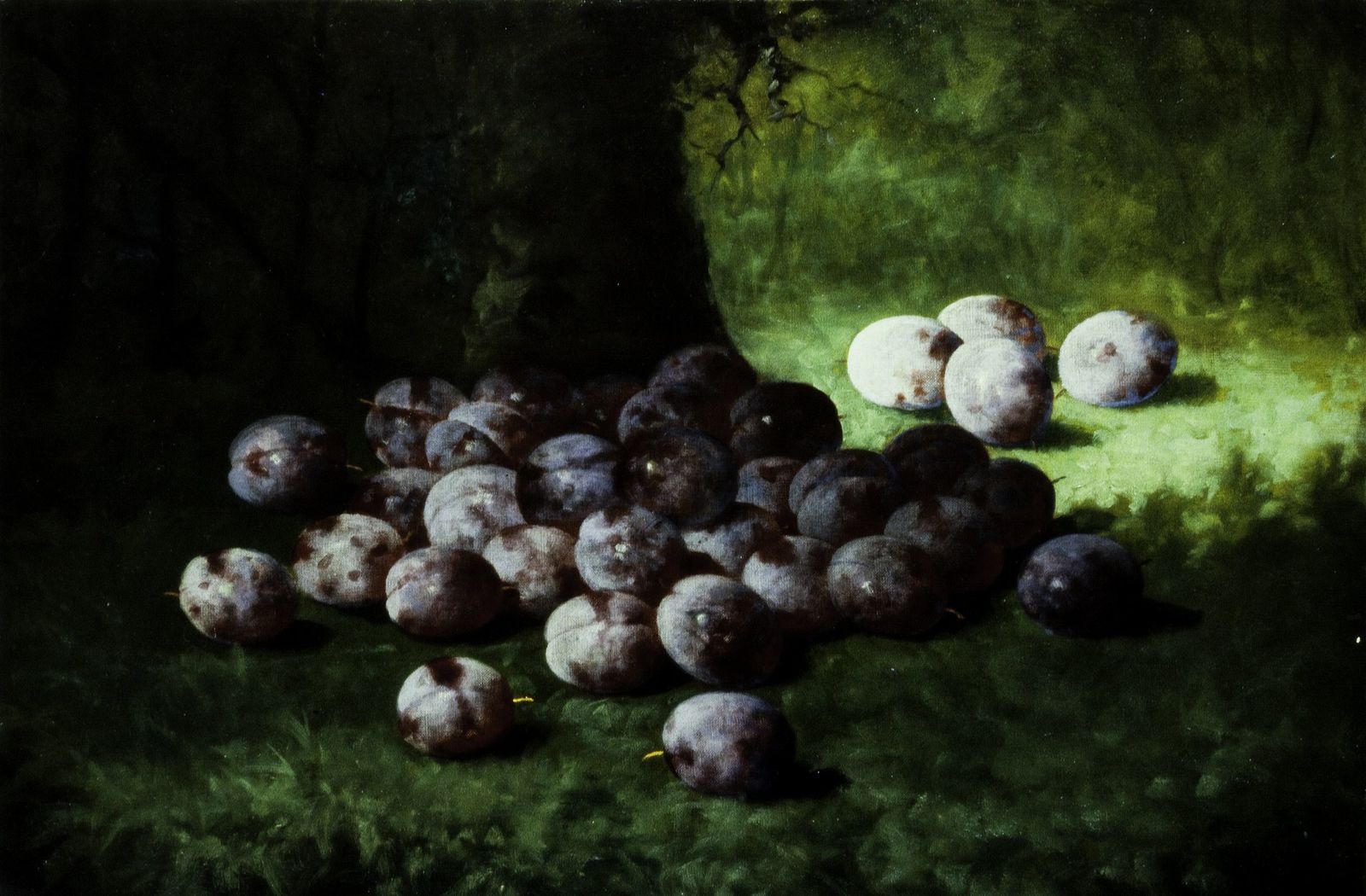

“Did you still want the plums?”

The voice is odd. It lacks rasp, it lacks heart. The smile I do recognize. His cheeks and the creases by his eyes remind me of sitting in between his legs, cradled in his arms, while he sat on the couch. I would trace his wrinkles with my pinky, pulling at sags on his skin and thinking that, if I tried hard enough, I would make them go away. Smooth them out and scare them away, if only I scraped my nails against them.

Apá stares at me, expectantly.

“What?” I say.

“There’s no price on the plums,” he repeats. “Do you remember how much they were?”

This was all wrong.

But his throat. The skin that loosely hangs from his neck and jaw. It’s all the same, but the timbre is all wrong. The words are not his own. Apá couldn’t speak English. He would try all the time. I would lie on the foot of the bed, my head against his feet and his leg hair tickling my ears. Only if you teach me, he would say, only if you teach me, then I will learn. I would run to the bag I had dropped by the front door in my rush to get in. The sparkly, green tassels Apá had sewn into it would always get stuck on the zipper. I would pull and tug and rip the thread until it gave, so that I could make my way back to him. And when they were worn enough, he would fix them back up again.

He would fix them after we learned. After I ran with my books and back to the room to teach. As if I had read the words and knew what they all meant, pointing at pictures of a giraffe or a mouse or a whale and sound out the words to him. I would tumble through the vowels with him, and slam against consonants I could not quite pronounce.

Apá would pretend to learn and to know what I was trying to say through words I’d never spoken before. Like how if I had a room in his house I would never have to leave him because the purple walls would be much too pretty and the make-believe bed with lemon colored sheets would grow mold, and dust, if there wasn’t someone to sleep in it every night. But he didn’t understand because those were words my mouth could never shape quite right.

We would both speak and try to understand. Our tongues a mess. But Apá would nod along, and I would nod along, listening to the nothingness, the willingness, between us. No real words, but a real memory.

So I know I have it all wrong.

Except his cheeks and his nose.

“Miss?”

I shake my head, force myself to look away. My shoelaces are untied, the aglets muddy.

“Yes?”

“Would you like me to check for you?” he asked.

“What?”

“The plums.”

“Oh. No.”

“No?”

“I don’t want them.”

Apá throws the bag on the belt next to him, doesn’t look at it again. The bag topples over, two plums tumble out and stop by his feet. He kicks them out of the way, scans the rest of the things I put on the belt.

On his wrist, a digital watch blinks big, blocky numbers on the screen.

The luminescent orange band makes his skin look yellowish, and his veins protrude in jagged zig zags from the back of his hand.

I grab the bags, make myself hold on to them, and head to the door. When I look back at Apá, he’s frowning at the next customer in line with two loaded carts of bright green sponges and translucent detergent.

I go outside, put the bags in my car, and go back inside.

* * *

The last people in line stuff boxes of chocolate bars and flavored caramel and cherry and mint into a single plastic bag. They chat softly about an office debacle and losing a bet. Apá listens eagerly, throwing his head back with a chuckle.

A heave and jumping ribs strain through the thin fabric of his shirt. I know that wheezing, that sort of breathlessness.

Apá and I would sit on the porch of his house during my visits, staring out at the street as cars passed by. I wasn’t allowed to see him often, but a few times per month Apá was all mine. One whole day at a time.

He would rock back and forth in an iron rocking chair that squeaked and croaked. One day, I ran over to the garden hose and filled up my small, plastic cup with water. The kind of cup that would wrinkle with use when I fisted it tight, ones we only used to throw out. The water sloshed over the rim, so I moved carefully and poured it on the creases of the chair where the metal had gone brittle and brown. Back and forth, I went and I poured water on the chair until it all pooled beneath it. I sat beside it, ignoring the water slowly soaking my pants, and scooped up as much as I could in my hands. I poured it on Apá’s knees, letting it trickle through my fingers and along his skin.

He looked down at me. What are you doing?

Oiling your joints, I said.

And he laughed, scooping me up from the ground and holding me on his lap, against his chest.

His lungs strained in his chest, blown up like balloons, and what if they popped? I thought they might pop and then he might die. What if he died because of the wheezing in his throat? Because of the air that refused to leave his lungs? Because they would grow much too big and wide, until they popped? I could see his heart hammering away through his skin. I hugged him tight and pressed my face, my lips, to his chest, hoping I could breathe air into him and maybe that could keep his laugh alive.

But he is not Apá.

Not Apá smiles at the customer, hands them a receipt and turns to look at me.

“Forget something?” he asks.

I set a new basket on the belt, fold my hands behind my back, and Not Apá loses his smile. His hair stands out straight at his neck like spikes on a collar. I want to reach out and prick my finger on them, in case they’re also fake.

Not Apá pulls out the items: a set of multicolored scrunchies, a box of double dipped Oreos, two bags of jumbo cotton balls, and a set of butcher knives.

He looks at me as he bags them up, tilting the screen to show me the total. He clears his throat. “Cash or card?”

Not Apá fists the bag in his hand, not yet giving it to me. The band on his watch is so big on his wrist that it dances up and down as he moves.

I glance at the total. “The knives are on sale.” I lie.

“You sure?”

I nod.

He looks at me, then at the screen. His knuckles whiten as they grip my bag harder. “I’ll get one of the managers for you then.”

“No.”

“No?”

“No need to bother anyone. I’ll just take them.”

“Well then, cash or card?” Not Apá’s mouth pinches tight. He extends his free hand towards me. Close enough to clutch at my shirt, in case I run away, I guess.

Not Apá wears a brown, knitted vest over a yellow shirt. On top, a blue, wrinkled flannel with all the buttons undone and a stain on the left pocket. His clothes swish around his body in bundles of excess fabric.

Apá had a big belly, and his clothes were always littered with stretch marks that mirrored the ones along his back. I wonder what it would be like to clutch Not Apá’s clothes in a fist and twist them around my hand. If I pulled at them tight enough, the vest and the shirt and the layered flannel might all stick to his body like a second skin, and maybe then he would just be Apá.

I look at his outstretched hand, the bitten nails.

“Your watch is broken,” I say.

Not Apá looks up. “What?”

“Broken.”

“Oh, I hadn’t noticed. I guess it is.”

I open my bag, pretending to look for something. Then I pretend to not find something, so that he’ll speak again. And maybe it’ll be Apá who speaks instead, a garbled tongue and mismatched speech.

“Miss, either pay or leave,” Not Apá says.

“Huh?”

“Do you want your things?”

“Yes, I’m just finding my wallet.”

“There’s still no sale. Is that ok?”

“Yes, that’s fine.”

“Great, it’ll be–”

“What about your watch though?” I interrupt.

People behind me mutter, impatient words graze the back of my neck. Not Apá won’t stop staring at me, and I wish I could stay here, staring back.

“Miss, you’re holding up the line,” he says.

The clock on Apá’s wall was so loud that he never looked at it to know what time it was. But I did. The golden hands swished behind the glass much too fast. I hoped that if I stared at them long enough, I could stop them. But Apá would tap my hand so that I focused on the carrots and the knife. The dining room chairs were so old that the springs would cut into the back of my thighs and the marks would stay there for days, even after I’d left. Sometimes, I thought they did it on purpose, to keep me there. A reminder of what it was like, so I’d never forget being there.

We would sit, and Apá would sing un letargo de azul, un eclipse the mar, and I didn’t understand. I never really understood what that meant and I never thought to ask. Peeling carrots and potatoes and yuca to store in the freezer, I barely had time to ask. Then Apá would defrost food we had prepped during prior visits, and he would cook and serve it for me to eat. The springs beneath the chair’s cushion gripping me in place. Never strong enough for me to stay.

I would look back at the clock again, scared.

“What’s your name?” I ask Not Apá.

He sighs, and that’s the closest his lungs have come to sound like Apá’s. Still holding my bag, he points to a name tag propped next to the keyboard.

Howard.

I never met a Howard before.

* * *

Howard leaves the store hours later. He shuffles along the sidewalk towards a car parked around the curb. His thin legs move his body along in tiny steps, exhaustion weighing him down. From my car, I see a blanket of rain around him that dampens his clothes.

My body moves on its own. I jerk the car door open and run across the parking lot. Howard doesn’t notice me until I’m a foot away. His eyes go wide, his arms jut out, and I wrap my arms around him. Swallow him whole in a hug he doesn’t return.

His body tenses, and the aged muscles of his arms bunch up. I can feel Apá’s papada against my shoulder, rubbing against my ear, and his warm, heavy breath at my neck. His lungs wheeze from years smoking cheap cigarettes and borrowed cigarros. And so his hair—thin as only gray hair can be—smells like tobacco too.

I hide my face in his shoulder and watch as my tears soak his vest, already wet from the rain.

He is tiny against me—wiry, brittle bones I don’t quite recognize. He stands with his arms against his body, and he won’t look at me. I want him to look at me because he might recognize my shoes or my watch or the tassels on my backpack.

Maybe he would remember me if I still wore my purple tights, smeared with paint, and the corduroy hat that hid my lopsided pigtails. Then his face would split open in a smile, his crooked, gapped teeth projecting joy across the parking lot.

I wish he would close his eyes and bury his face in my neck.

Apá embroidered stars along the rim of my hat in every single color thread he could afford to buy. When it was done, he slapped it on my head and I could barely see from beneath it.

I left it somewhere in his house after my last visit.

* * *

Image by Carducius Plantagenet Ream via MIA