I

Is it always the nature of grief to make you wonder, what if? If it isn’t, then why do these shelved memories—of the fetus you tried to bury, of the affair with the diver, of the beginning of the unraveling of your marriage to Kene—come unbidden? You aren’t sure.

But here you are banishing those memories, pouring them into the mixing bowl, along with the pancake mix, the beaten eggs, the salty liquid that flows unbidden from your eyes. Outside, chirping crickets and ribbiting frogs announce the end of the witching hour. And just as you twist the on-knob of the gas cooker, the crick-ribbit chorus quietens, and the hushed conversations filter in through the gauzy kitchen windows.

Listen to Kene’s familiar deep voice muttering, and then to your mother saying, “Go well, Kene. Leave before your wife awakes and flings herself into the toddler’s —”

When her final words get swallowed up by Kene’s zooming car, resist the urge to plunge the bread knife into your heart. Soliloquize. He’s gone to bring Zara home from the antiseptic-smelling freezer truck in which she had been wrongfully entombed alongside other victims of the COVID-19 virus.

Scoop a spoonful of the pancake mix into the heated pan. Listen to the sizzle, pop and fizz of the pan. Hear the sounds as Zara would mimic them. Sizzle, pop, fizz. Imagine her flailing her arms like a polyp in a coral reef, sizzling, popping and fizzing. Imagine her pausing to tuck her oh-so shiny dreadlocks behind her ears.

Flip the pancakes. Perhaps the aroma will travel to wherever they took her and wake her. For isn’t she stuck in a dream where she’s playing cook with Mama?

She must be.

Just three weeks ago, before she was admitted to the hospital for malarial fever and bronchitis, before she contracted COVID-19 from another patient, before you and Kene were banished into the quarantine center, she had asked, “Mommy, Daddy! Will I help to fry pancakes once I’m well?” And you made her that promise. And so here you are flipping and frying Zara’s favorite, well-seasoned with tears.

II

But today, Zara’s overpowering smell wafts in with an earthy dawn breeze and moves you out of the house. Not in your nightgown, but in your gray workout gear.

Brisk-walk to keep out the cold. Be blind to the waving neighbors, deaf to their greetings. In your head, Zara sings, “It’s cold. It’s super cold.”

Further down the street is the Blessed Tansi Catholic Church, where Kene often took you and Zara to Mass. Your brand of Protestantism accommodates your husband’s Catholicism in a mixed marriage that once transmogrified into what you and Kene termed an “open-mixed marriage.” Unsanctioned by the church, of course. Six years ago, after his necrospermia diagnosis, your husband came home with images of men pulled from Facebook and Instagram. “How about this six-packed dude with his glossy skin?” Kene asked.

On another occasion, he said, “Is your handsome account manager back on the market? His relationship status on FB reads, ‘it’s complicated’” Even when your hands hurt from shoving away his brightly lit MacBook, even when you rolled your eyes and said, “Not my kind of man,” and “Not interested,” Kene never let up. Your eight-year long marriage was inching towards the tricky ninth anniversary and he was desperate to populate your union with children. It seemed odd for a practicing Roman Catholic who preferred his own company to talk nonstop about “the pros of seeing” other people. He gave a long-winded speech about reducing the feelings of guilt and jealousy by “jumping into those murky waters of the dating scene as a team” and “egging each other on.” When you got pregnant, he argued, the baby would “resemble one of us” and the rumormongers would stop speculating about “the emptiness of our childless marriage.”

You heard what he was too broken to say: the necrospermia diagnosis wasn’t the only motivating factor. His stepbrother had called him an “impotent eunuch” at a family gathering, and though Kene had sucker-punched him, the words stung and filled him with an obsession to prove his virility.

And about a year after you’d rejected Kene’s proposition, Constantine reggae-danced into your life. You were thrilled by the novelty and the mystery of the dreadlocked diver. It was around this time that you stopped attending mass at the Blessed Tansi Catholic Church.

And now, here you are brisk-walking past the church’s long street, past the Trans-Woji bridge with its waters crashing into rocks, rushing towards the Atlantic Ocean. Stop and look over the railings into the silvery, frothing waves. If you dove into the water, and the tides swept you away this life into an island of coral reefs, would you morph into the kind of mermaid who sinks ships with her singing, the kind who never mourns?

Lift your left leg over the railing. Breathe. Raise the right leg and halt to the strident shouts of “Hey! Hey! Stop! Craze-woman!” And as gravity forces your right leg down on the tarred sidewalk, pull back the left leg. Scan the faces to see who called you a craze-woman. Wipe off the tear trailing down your cheek, shudder at the thought of your body smashing into river rocks, consciousness fading into the ether. Stomp your feet. Jog around the corner. Race past the filling station, past the antique shop with the scratched reef marine aquarium on the display window. Freeze.

Goosebumps wash over your skin as you recall Constantine’s living room, the gowned Jizō statue in his coral reef aquarium,the polished brown face and the dimpled wrists of its hands clasped in a prayer pose and Constantine saying, “it’s a memorial, a water baby shrine, for my stillborn daughter in London.”

Constantine’s residual voice goads you through the swinging doors of the antique store, where you lift the aquarium onto the counter. There’s no jizo statue. Just two sad-looking tetra fishes swimming in its two and a half gallons of water. Yet you say, “ I left my purse at home. Can I take this and bring the payment later today?” The shopkeeper says, of course. You are, after all, one of her regular customers. Hoist the aquarium into your arms. Hurry out of the store.

“Zara, are you near?” You mutter as you trudge past the unfamiliar cars lining your street and crowding your driveway. Only a lunatic will flout the lockdown guidelines to have a pandemic party on a Tuesday morning. Stagger up your oyster shell-bordered walkway.

The door is ajar; swings back when your shoulders nudge it open. Step into the sitting room, hold your breath. Yes, there are relatives, friends and friends of relatives helping themselves to your pancakes. The stainless-steel tray is empty, save for crumbs. You do a headcount. Eighteen people are sitting or standing one meter apart. A social-distance gathering.

Oh, not really. Kene is sitting at the dining table with milk clinging to his mustache, giving it the appearance of graying hair. Perched beside him is Ify, all scarved and gloved and masked in matching print wax material that sets off her glowing olive-complexioned skin. She tugs the sleeves of her off-shoulder blouse and smooths the wrinkles on her bell-bottomed trousers. It’s the first time you’ve seen her since you were pregnant with Zara. As you watch her patting Kene’s back with a gloved hand, you find her manner intimate and unpleasant. So you glare at Kene.

You push the aquarium into the hairbreadth of space between Ify and Kene, until the space widens to sit the water container.

“Did you bring Zara home?” you say, beating on Kene’s shoulder as though it is a door you want to crack open.

“She—no, her body—is government property,” he says, holding a saucer of pancakes between you.

“Sue them. What if she’s trying to get out of the body bag?”

“Kasarachi, please stop.”

This isn’t how you expect your daughter’s father to grieve. Cuddling with the ex while Zara is God-knows-where?

Your mother rushes out of the kitchen, mug in left hand, bread knife in right hand, mouth stuffed with pancakes. “Kasarachi,” she says. “Where have you been? Everyone has been trying to offer their condolences.”

You want to say: This is why I detest funerals. Funerals are trouble. Funerals are friends and relatives and friends of relatives gathering to deliberate on the misfortunes of your life.

But before you can mouth these words, mournful faces present themselves. Your mother-in-law overshadows them all with her impossibly high afro, shaped like a mushroom jellyfish. Her boombox voice pipes a notch higher. “Kasarachi, I’m still in shock!”

Shake your head. Say, “Mama, I don’t want to believe this is the end.” Your eyes and cheeks sting from holding back a storm.

Your mother-in-law reaches out to rub your shoulder but lifts her hand to scratch an itch under her afro. “ You’re still young. You can still have another one,” she says.

Think: Why would I want to replace Zara? You have heard your mother-in-law make wicked suggestions to a childless woman. “Marry another wife for your husband,” she had said to the other woman as if infertility was the sole preserve of women. “My step-mother paid the dowry for my own mother. That’s how she filled her husband’s house with babies. ”

She will not say these things to you, because she is mourning her granddaughter. She loved Zara, bought her educational toys and clothes and body oils. Even now, her wrinkled cheeks are stained with tears.

Lug the aquarium into the master bedroom, place it on your reading table. Secure the locks to the door. If your heart feels heavy with inexplicable grief and longing it’s all because you can’t nuzzle Zara. You can’t kiss her forehead or do the mosquito dance with her. And you think you’re being punished again for not burying the first fruit of your womb. And you’re curious about the presence hovering above you again, pressing down on the parting on your head.

Open your diary. Start the sentence with ‘I.’ Cross it out; start with a ‘you’. It’s easier to frame this narrative from the perspective of your youness. “I” hisses as though your heart is seared with a branding iron.

III

Take four pictures out of Zara’s photo album. Brush each photo with the tip of your finger. Linger at the shiny dreadlocks and the stubborn chin that yielded to open-mouthed laughter whenever Kene tickled her ribs. Constantine’s dreadlocks. Constantine’s chin. Well, it was Zara’s bright eyes that Kene proudly showed off at family gatherings, during Mass, at playgrounds. Even now, you can hear Kene and Zara giggling over sweet-nothings and singing nursery rhymes in Igbo. Drop the pictures into the aquarium and watch them sink to the bottom. Then walk away.

Traipse around your four-bedroom flat. Searching the corners of the house, the crevices of your soul. A presence corkscrewing around you the way Zara used to. Yawning in your soul is a Zara-sized hole. Groan.

Pace like you did in your off-campus apartment after you had an abortion in that nameless, soulless clinic at Mile 1. You were a twenty-year-old rape survivor, in your second year at the University of Port Harcourt. Even now, your heart flounders wildly in your chest at the thought of scanning the sunlit, lonely street for the police before waddling through the varnished mahogany door. The receptionist barked at you because your hands shook while you filled the registration forms. You didn’t mention that you had slipped misoprostol pills into your cervix and that you had been in active labor for six hours. A cornrow-haired girl chewed gum loudly and complained that you were holding up the line. You apologized and handed her a pen. She couldn’t have been more than thirteen. An hour later, she sauntered ahead of you while you waited for your cervix to dilate more.

Soon it was your turn. Your hands shook as you peeled off your underwear and lay on the table, your teeth clenched; the abortionist’s-gloved hand slipped into your cervix before you had a chance to wonder about its unsanitariness. But you live in a country where abortions are illegal. It didn’t matter if you had died on the table. So you smiled when the doctor announced, “No need for a D&C. Your baby arrived whole”. You hoped to leave with the fetus. Better to bury it yourself than to have the quacks sell it to potioneers. But alas, your request was met with a dirty look and a plume of marijuana smoke. For the next two weeks, you cry, bleed and pace in your apartment thinking, I should have fought to bury my own fetus.

Nineteen years have elapsed, and yet traipsing around the four-bedroom flat drains you, like regret.

Now, you regret the times you had scolded Zara for turning the house upside down, for putting potatoes and onions in socks and shoes, for breaking the screen on your iPhone, for scream-singing. Kene often said the walls came alive whenever Zara’s voice bounced off them. You’ll give anything to hear Kene and Zara sing along to a Igbo rhyme or folksong.

Time folds in on itself and the weekend ends with your legs pulsating from the endless pacing. You cannot bring yourself to teach Evolution to your Biology students via Zoom. When you aren’t picking at your breakfast on the kitchen counter or forking around your lunch in bed, you sob. For dinner, you eat a bowl of fruit salad in the living room while Kene shakes his boxing glove-sized fists and yells at the people in the News: Lai Mohammed, Trump and Fauci, WHO and the Madagascar government. Scientists are developing a COVID-19 vaccine. Hundreds die in Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister of the UK is in intensive care. Hundreds of corpses are packed in refrigerated boxes like Zara.

It takes seven days for the fissures to appear in Kene’s fortress. After watching the news, he locks himself inside the guest toilet and weeps. His sobs lull you to sleep on the living room floor. Zara struts towards you in a buttercup-hued sundress. Two jet black ropes of dreadlocks stray from the bun atop her head and dangle in front of her left eye. You croon her name and open your arms wide, inviting her to hug you. She pauses and says, “Why won’t you let me go? You have to let me go!” You bolt up in bed, wide awake, drenched in sweat, howling.

Narrate this dream to your husband and your mother and to your sister when she calls from Hong Kong. End each retelling with a cry and an itch to scrub the house with bleach and disinfectant. Launder and pack boxes of toddler clothes, Merriam-Webster’s First Dictionary with Illustrations, pink toiletry bags and jumbo building blocks set to the Catholic Church orphanage. From the orphanage,drive to the FedEx office to mail Zara’s pictures to your sister’s hotel room. Don’t forget to pay for the aquarium on your way back from the courier’s. And while the store clerk counts your change, narrate your dream to her. But resist the temptation to share it on social media. Constantine might be scrolling.

IV

If you hadn’t accidentally grabbed his suitcase from the airport baggage reclaim, Constantine wouldn’t have taken yours. But it so happened that you’d both wound up at the Port Harcourt International Airport, strange suitcases in hand, trading insults over whose fault it was that you’d both gone home with each other’s heavy baggage.

The airport manager claimed responsibility and said he was sorry that the security officers hadn’t been around to check the tags. You didn’t notice Constantine’s stubborn mouth and the umber tips of his dreadlocks until you were both out in the sunlit parking lot, lugging your suitcases in the rain.

When he said, “My apologies. Need a ride?” you ignored him and looked around for a taxi. But the rain had done to the taxi drivers what smoke does to mosquitoes—dispersed them. His offer was your best bet, so you said in your fakest voice, “A lift will be appreciated. Thank you.”

He peeled your fingers off the handle. The smoothness of his uncalloused hands made you wonder if he had spent most of his life getting fish spa treatments.

He drove like the oil and gas expatriate that he was, carefully, horn-averse. You wondered if he was one of those black British men who had chauffeurs but didn’t like the idea of using their services. Perhaps, he was. You gave him directions until he pulled up beside the giant black gate of your school.

“Is this where you teach Biology?” He asked.

You scratched your cheek and nodded. It was obvious that he had gone through your stuff as much as you his.

“How risky is it to work as a deep-sea diver?” You asked, as you dragged your suitcase out of his boot, out of his life.

Or so you thought. His detailed handwritten letters began arriving at your office; one per day, for thirty working days. Each couriered letter sharing details about his life as a saturation diver and a recovering marine conservationist. Each letter arrived with gifts Londoners like him offered: flowers and water-themed postcards and chocolates. His un-Nigerian love gestures made you laugh and made you shake your head with pity. “Mr. Constantine,” you said when you finally called his number. “This is no way to woo a Nigerian woman, certainly not a married one.”

But by the end of the phone call, you had consented to meet with him. Constantine had had no qualms being vulnerable with you. You sat on the soft leather couch listening to the regret in Constantine’s voice as he discussed his routine as a saturation diver; replacing oil pipes and shoveling mud when he could be discovering what new species were being spawned and which genuses were becoming extinct. “The figures on the paychecks.” Constantine kissed his fingers and whistled. “Makes you feel you’re kissing working class life goodbye. Blimey, these oil industries offer saturation divers much more than marine biology labs and the National Geographics of the world.”

As he talked, you nodded thoughtfully, recognizing the dilemma of being torn between two loves—one wealthy in the capitalist sense, and the other, sublime. You wished you had pursued marine biology too, not settled for biology education; but like Kene, you were averse to displays of penitence, all invocations of repentance.

You could have told Kene about the relationship, but you were uncertain about where this thing with Constantine was going. And there was the excitement that came from the spontaneous meetings and the deception you peddled from the bedroom you shared with Kene to the settee in which you lounged with Constantine. The excitement that came from seeing someone who spoke fluent oceanography and took your mind off a guilt complex you’d been suppressing for years. And it was satisfying to know that Kene hadn’t strayed. Yet.

As the days wore on, you blamed your inexplicable yearning for a space to reimagine the possibility of going diving. Of course, you’d been addicted to the adrenaline rush that came from sneaking around.

And on the third night—after Constantine told you about his plans to get a post-doctoral degree in marine conservation—you didn’t resist his hungry hands and lips. He’d waited for months since he poured out the contents of your suitcase on his bed. And now that he had you under him, he couldn’t help but weep in excitement,“at last! At long last!” Yet, you indulged him. It didn’t matter that Kene was more attentive during foreplay, more experienced at lovemaking, and that you were a little distracted when Constantine slid inside you.

Two woofer speakers amplified the snapping and whopping and purring choruses that arose from the bioluminescent coral reef aquarium on his shelf, drawing your attention to the colors. The olive greens and buttercup yellows and mandarin oranges of the floating island no longer shimmered with brightness as they had two weeks earlier, when you first pulled out Issue 19: Journal on Coral Reef Islands in the 21st Century from Constantine’s bookshelf.

“Bleaching,” you murmured.

And Constantine held still and breathed lustily into your ear, “What did you say?”

“The coral reef island. In the aquarium.” Brushing the creases above his saucer-wide eyes, you added, “It’s bleaching, you know, the rising temperature of—”

“Shhh,” he interjected, planting his warm lips on yours. But not for long as your bodies transitioned from the missionary position to a pose that would have been perfectly suited to your thirty-five-year-old body, if it’d been versed in the practice of extreme gymnastics.

You didn’t mind because you got a better view of the bleaching coral reef. Like this reef, your marriage with Kene was suffocating. Your eyes locked with the bold stare of the Jizo statue with its ox-blood colored bib and blood red bonnet as Constantine groaned and pulsated inside of you.

V

Kene spends the entire weekend incinerating the serrated-edged kites he constructed with Zara. You shut the windows to keep out the choking smell of burning plastic. But the windows are transparent enough for you to watch the tall flaming tongues leaping into the sky and as you do, you re-imagine Zara palming down the plastic bags, placing the longer raffia broom sticks over the shorter sticks and yelling ‘t!’ because the frame of the kite formed a small letter T. In the last inferno, you hear Zara’s squealing embedded in the crackling fire. The squeal she let out as her father carved the plastic bags with his favorite serrated edged bread knife and secured the frame to the plastic bag, and glued two polyethylene tails to the edge of the kite. The squeal gives way to the slap-slap of Zara’s running feet and her high-pitched cries of “Flee kite Flee!” The tongues of flames morph into several tiny yellow kites flying against the smoky blue sky. Only God knows how many kites Kene made for her.

As the last of the kites smolder in the garden, you swing around and see Kene eyeing the toy car wash and doll house he’d been planning to surprise her with. You know they will be the next recipient of his rage. And you’ll have to rely on the shut windows to shield you from the painful noise of his choked sobs. Even Ify hasn’t been spared this silent rage. These days, he ignores her calls. When he picks up, he mumbles monosyllabic responses.

While they are at it, you yawn; too tired to care. All your energy goes into sorting and arranging Zara’s photos. One for each passing day.

To commemorate the tenth day of Zara’s death, you curate ten passport-sized photos and crowd them into the aquarium. One for every kiss Kene gave Zara upon your exit from the delivery ward. Staring at you is a portrait of a grinning Zara, and a bright-eyed Kene—his afro gleaming healthily with eumelanin, his pursed pinkish lips planting a kiss on Zara’s cheeks.

Later at night, you lie supine, counting the partitions on the ceiling. Your body yearns for the warmth of another body. You can’t explain this sudden need, but the surprise doesn’t stop you from tiptoeing down the corridor into Kene’s room. Snuggle up to him and kiss his neck. Caress him and whisper, “I need you.”

“I’m too tired,” he groans sleepily.

Bolt up and pull down his pajamas. “I can help you with that.”

Outside, two thunderbolts roar.

“No.” He pulls up his shorts. Fat rain drops drum on the pane of glass. “I’m not in the right frame of mind.”

You think: he’s no longer attracted to me. Perhaps he wants a second wife. Perhaps he wants a spouse who will never come home smelling of another man’s Jamaican peppersoup pot, or another man’s cum. Your mind conjures up a vision of a younger wife,, sashaying in and out of the rooms of your four bedroom flat, swinging brandy-hued braids that brush against her large buttocks.

Unbidden tears roll down your cheeks and slide onto his unshaven chin. His bare shoulders shudder. Plant a kiss on his clavicle. But resist the urge to let your lips linger. One kiss is enough to comfort him through one night of grief. Wipe the rest of your tears with the back of your hand. Storm out of his room.

VI

In your room, the reflection of a lightning bolt flashes across your bed. The lazy rumble of thunder precedes the persistent drumming of fat rain drops. The music puts you in mind of that rainy night four and a half years ago, when your marriage faded into a bone-whiteness.

You remember walking through your living room door, tossing your key on your center table and hugging Kene from behind. He sniffed. Perhaps at the earthy, garlicky scallions or the nutty, bitter callaloo on your breath. Then he turned to face you. Down rolled the flame-shaped okra he had been slicing with the sharp bread knife.

“What did you have for dinner?” he asked, in a tone so playful, it made you put down your guards.

“Jamaican peppersoup pot,” you blurted out, picking up the green okra.

His lips stretched into a mock smile; his hands gripped the wooden handle of the bread knife. “At the PTA meeting?”

“No.” The staple refreshments at PTA meetings were meat pies and Fanta, not Jamaican cuisine.

Sniffing again, he said, “I can smell him on you. ”

Your eyes latched onto the knife in his hand. Why was it so easy to extricate the right answers from you? Perhaps, it was his skill as a lawyer or it was the knife in his quivering hand. Or perhaps it was the exhaustion from all the gymnastics of the oh-so slow lovemaking at Constantine’s. So you leaned against the wall, biding your time as he pontificated about the benign and malignant types of adultery, and open relationships like the armchair theorist that he was. When you couldn’t bear it any longer, you interjected:

“So it took me one year to—”

“Take advantage of the situation?”

Up in arms, you shouted: “You wanted an open marriage!”

“For children, yes.” Sighing he added, “You said, ‘not interested.’”

“That’s not fair,” you cried. “It was your idea.”

“Is that the most convincing excuse you can come up with?”

The words gushed forth through Kene’s clenched teeth, the white lights from the fluorescent tubes glinting off the serrated edges of the bread knife. Fear made your tongue a leaden spoon in your mouth. The lazy rumble of thunder floated in through the window, into the space between you and him.

Although you had wanted to, you couldn’t say that there wasn’t a mutual exclusivity between his supposition and your decision to sleep with Constantine. And you couldn’t bring yourself to say that you hadn’t adulterated anything. In fact, there was no stock of pure breeds to spoil. But you knew his ego was bruised and that he couldn’t be blamed for having necrotic sperm cells. So you clamped your lips shut.

Kene charged and roared and knocked a whole basin of okras to the floor, his breath rising from his chest in noisy heaves. More light bounced off the serrated edges of the knife and glinted in his wet eyes.

“Why hide the whole koko from me?” he cried. “It’s the lies and betrayal that hurts.”

“But, I didn’t think you’d want to know!”

The refrigerator chugged; the power went out. Fumbling for your phone in your handbag, you bit the bottom of your lip to keep from howling. The LED lights on your phone cast a glow on his receding shadow as it stormed down the corridor into the guestroom.

“Kene?” The flashlight on your phone came on. “Wait.”

He held up the bread knife. “Don’t you dare come close.”

Slamming the door behind him, he snapped the bolts, turned the locks twice. You kicked the door and growled and roared. You tried to pack your things. It was easy to fold your clothes into your suitcase, but your best photographs were his too. Dividing them down the middle would ruin them so you left them and picked up the towel that smelled of his Old Spice shaving cream and the Gucci sandals he bought the previous year, when you turned thirty-five. Ring finger in your mouth, you bit your wedding band and slid it onto your tongue. Its stinging metallic tang smarted your cheeks, until you crouched and broke into choking sobs.

It was in this squatting pose that you sent Constantine a text message. You don’t remember the exact wording of the message, but you do know that it was harsh and insincere, and that as you blocked his number, rivulets of tears rolled down your cheeks.

When the neighbor’s rooster crowed the next morning, you went to the guest room door and called his name. No answer. The sliver of space underneath the door revealed moving feet, which you watched as you listened to the sounds of his heavy breathing.

You left a tray of food and jars of water on the dining table. But when you came home from work the bread had hardened from exposure, the runny eggs spotted three dead houseflies; the milk in the beverage curdled on the edges of the teacup. And the door stayed locked.

The following day, you peered through the sliver of space underneath the door, saw his barefooted pacing, heard his heavy breathing, and decided to leave the tray of food and water in front of the guestroom, where a bump from the door would have spilled some of the soup and water. And as you taught pupils about life forms and living things, you imagined a cloaked, hunchbacked death skulking along the corridors of your home, pitchfork in hand. What if you came home and found that Kene had stabbed himself to death with the serrated bread knife?

The pungent smell of rotting fruit salads, soured soups and moldy garri hit you as you unlocked the living room door after work. Tiptoeing to the guest room door, you listened to the sounds of breathing, and pissing and cracking knuckles. Eyes raised to the heavens, you muttered, “At least, you’re alive.”

On the third day, you awoke to the loud whistling of the pressure pot. Your first thought was burglary. Tiptoeing down the hallway to the guest room door, you rapped on the door and said, “Please Kene, there’s a burglar in the kitchen.”

Silence.

“Please, come out and help.”

The banging of pans drew you to the kitchen. Through the keyhole, you could see an unshaven man march around the kitchen like the man you had been married to for nine years. A slight push, and the door yawned open to reveal a stone-faced Kene stirring a pot of reddish-brown beans and plantain porridge. You slapped your hand over your mouth to keep from screaming about his jet-black hair suddenly turning gray.

* * *

And so, you awoke each morning, thinking you’d stay, just one more day, in your section of the four bedrooms even when Ify the girlfriend sashayed into your lives, first visiting one rainy weekend from Etche, fiddling with your turntable, whistling to the tune of some obscure music, swinging brandy-hued braids that graze her large buttocks. You stood transfixed at the door saying, ‘who are you? why are you here?’ Tracy Chapman’s voice boomed from the stereo as Ify swung around and said, “I’m Ify, Kene’s girlfriend.” Kene waltzed in, a bottle of Hennesey in hand, only freezing when his eyes met yours. How long did you stand there glaring at each other? One minute that stretched into a millennia? Perhaps not. But you do know that as you clenched and unclenched your fist, that you wanted to punch him in the mouth and to rip off Ify’s bum shorts.

But all you did was storm into your section of the house while Ify traipsed around the flat swinging her voluptuous hips. Even when you could hear Ify shrieking with delight from the caverns of the guest room. Even as you developed a heightened sense of smell that turned your stomach every time she sauntered past your door and left a trail of citrus. You stayed and soliloquized about staying just one more day in this house, with this man you once thought you could never live without.

But this was the era of nonsensical happenings, when you were always on the chancy side of statistics. According to an HSBC study, there’s a one in fifty chance of finding a romantic partner on an airplane. You did. Also, there’s a 30% chance of conceiving in your first month of trying. When you heard this from your gynecologist, you never thought it would happen to you.

Also, you never envisaged that Kene would be so excited by the news that he would abandon Ify in the guest room, and cross the invisible barricades to say, “sorry, ndo” while you retched into the toilet. You were shocked when he smiled at the bump on your stomach and said, “Kaka, you’re pregnant.” Shocked because you’d been in denial, because you’d been ignoring each other for twelve weeks since Constantine

Yet, you nodded and whispered, “yes.” even though you hadn’t expected Kene to say, “Let’s get you to an antenatal clinic.”

VII

A post lockdown Monday morning. The room smells of Peak 123 milk and rain. Slivers of dawn light streak through the curtains. Wear regular teacher’s clothes—a beige suit, dangling earrings and sensible leather shoes.

As you stride through the tree-lined entrance of the government school, keep your chin up. You’ve worked here as a Biology teacher and a guidance counselor for eight years, but you’ve never felt so empty, so inadequate, so lost. Not even when Constantine sent you his last postcard, the one that read, “Hello Kay Love, I’m sorry to see you go.”

Sit in your wood-partitioned office, and wait for teenagers to waltz in and say, “Ms. Kasarachi, will there be a second wave of the pandemic?” Or “Are we experiencing the apocalypse? Or, am I in love?”

Hand out flyers absent-mindedly. Acknowledge the emptiness in your soul. The Zara-sized hole.

During break, while the kids play football and basketball, screaming their heads off, the school Principal walks in and says, “Kasarachi, kedu? I hope you’re stronger.”

Nod. And say, “Good afternoon. Sit.”

“No. no. I won’t be here for too long,” The school principal says.

Think: like Zara. But say, “Okay.”

When she says, “Sorry for your loss.” Flash a tight smile that says; can you believe it? — I just lost my baby. I don’t know where to find her. I know where her body is, but she’s no longer in it.

Exhale. Then say, “If I could fight God, I would. Anyi a ga aba Chukwu ogu?”

The Principal nods like an agama lizard. “Have you heard of urine therapy?” She says, shifting her weight from one leg to the other.

“Urine therapy?”

She nods and her voice goes down a notch. “You know it cures convulsions and viral infections in children. My first son convulsed when he was eighteen months, and on my mother’s advice, I forced my urine down his throat.”

Clear your throat. Say, wide-eyed: “Were you crazy, really?” Then palliate that rudeness by saying, “Sorry, urine stopped the convulsion?”

“It worked like magic.” She snaps her fingers. “At least it worked for me. And I heard some COVID-19 patients recovered after they’d tried a combination of herbs and urine therapy.”

On your way home from work, ask Kene if he has heard of urine therapy. Don’t ask him if his mother fed him piss.

He furrows his brows. “Urine what?”

“Therapy.” Repeat the school principal words. Talk with your hands over your head.

“I don’t understand a word you’ve just said.”

Sigh. Tell him to take you to the movies; it won’t be a super-spreader event. All moviegoers will have to sit and watch from driveways and parking lots.

At the movies, he’ll caress your arm and kiss your shoulder. Fill your mouth with popcorn and stare at the screen. Try to remember the title of the movie or why you chose it.

“Excuse me.” His sexy baritone whisper will startle you. “Off to the gents. I’ll be back in a jiffy.”

Go with him. Admire the way his jeans cling to his flat bum. Take in the turned up collar of his Arsenal T-shirt and his oversized moccasins. When he comes out wiping his hands on his jeans, don’t slap his bum. Say, “You boyish man! Where’s my lawyer husband?”

“He’s still mourning so he asked me to show you some fun.”

Lean into him. Pour all your grief and frustration and hopes into the kiss. Let the tears roll down your cheek and then, push him gently away. Back at home, bid him good night and sashay into your bedroom alone. Sigh. You know what all good teachers know: pedagogy is fifty percent acting.

And acting, like mourning, is all about feeling.

VIII

You’re lying in bed daydreaming of fat-legged babies pirouetting in tutus atop an aquarium. Zara’s voice booms out from behind a series of swiveling doors. “Let me go,” she says, in a quieter, more matter-of-fact voice. “I have to go.”

Your eyes flutter open. Yellow bars of noon sunlight fall atop the aquarium; its disintegrating pictures swirl like strange underwater creatures. The door swings open and your sister saunters into the room dressed in a flowing ankara gown, smelling sweetly of citrus. “Ginika!” you say, as if you hadn’t heard she’d flown back after the border had reopened. You act surprised for her sake. Gnika likes to surprise you, like FedExing you the exact kind of brandy-filled boxes of chocolate Constantine bought when he was wooing you. But your sister doesn’t know anything about Constantine and she is eager to hug you, eager to say, “Kasarachi, I’m sure you have heard enough sorrys to last you five reincarnations.”

Hum softly when she makes small talk. But when she throws a protective arm over your shoulder and says, “Quick. Get dressed. We’re going to Freedom Stadium for a gospel concert.”

Brush off her arm, say, “Concert? With social distancing?”

Ginika flashes a smile. “Tickets and snacks are on me.”

Skip lunch and dinner so your stomach won’t bulge through your favorite silk shirt Ginika bought you. It’s a ChiJesu and Ebelebe concert. A pair of jeans and a shirt will be perfect.

The stadium is packed full of masked and gloved fans. Each person has a vacant seat to their left and right. Ginika flashes your VVIP tickets and you slide into second row seats with the creme de la creme of the Niger Delta.

Thank Ginika for the cup of juice and roasted meat she hands you. Empty the cup in three quick gulps. Near the retractable roof of the stadium, a bevy of ladies are singing, through surgical masks, at the top of their lungs while rocking on their feet.

“The year D and I moved to Holland, we had a child who died.” Ginika bows her head as though in a prayer. “A son.”

Stare at her with mouth agape.

“I didn’t know that,” you say, after the rocking ladies stop singing a chorus. “Did mummy know too?”

“I was too depressed to disclose the birth of the baby. Let alone his death. I forbade D from telling anyone.”

Ginika closes her eyes. “He came prematurely. At seven months. Was alive and suckling for three days. And just when I got used to keeping awake at night and all, he just went puff!”

Stab a piece of meat with your toothpick, mutter. ““Oh my God.” You don’t know what else to say, because you would never dismiss your loss as something that happened thirteen years ago. You would never say, “I don’t dwell on it too much” because you aren’t like Ginika. .

With a gentle squeeze of her hand, try to rekindle a kinship spirit.

“But how—”

“Shush.” Ginika points to the stage and you sigh, feeling absolved of the guilt of hiding your abortion from her.

Onstage, ChiJesu is plunking a soulful symphony on his piano. Ebelebe is strumming his guitar. The atmosphere is charged with singing and swaying. Sometimes, you sing whatever song they are playing. Sometimes, you drift down memory lane, conjuring long sleepless nights spent nursing, changing diapers, cuddling, and chatting in babynese. For some reason, your mind flashes images of the near cot death, Zara’s mouth foaming with breast milk; a pajamaed Kene driving her to Briggs Pediatrics Hospital.

When the tears start flowing, don’t wipe them away. Stand and sing in an angry voice, then hum songs of salvation, and of un-disappointing hope. Shiver under the weight of the lyrics, at once pressing down on your chest and lifting off your grief in slow portions.

A cold hand tugs at your outstretched hand. It’s Ebelebe, guitar slung across his shoulder blinking tears from his eyes. He says: “Come. Dance upstage.” The cold from his hands grip yours.

Shake your head no. Sway to the new tune ChiJesu plays, your favorite, Zara’s favorite, Forsake Me Not, Lord.

“Go on, you dry woman,” Ginka mouths, her head bobbing slightly.

Walk upstage with Ebelebe. Step gingerly as though you might slip on the wet grass and fall. Yes, God has forsaken you. Throw your hands apart and twirl like you saw Zara do in front of the TV once. Call up memories of dances with Zara, of plans to register her in an elite ballet class. Swing, glide and step back. Your sorrows won’t fly away but swing your arms and twirl. It’s all you have now, a grand chance to let go, to soar like a bird, with your heart hanging hollow. Ebelebe catches you to steady you. When ChiJesu plays the coda, remember the hopelessness of that cold, dingy abortion clinic; the blindsiding pains you trapped within you as a yellow cab drove you to your dormitory.

Twirl. Think: Does Zara dance with that nameless baby? What’s this life worth? Dear God, at least music moves you, shakes the foundations of your being like an earthquake. Fall on your knees. Your life is not your own.

IX

At home, Kene shuts the door behind you and says, “How did it go?”

Grin at him and walk into the guest room. Say: “Hmmm Ebelebe was so impressed, he gave me his jacket. See?”

“I can see. But please tell me if you decide to start seeing him.”

Slip out of your sweat-drenched clothes. Say: “That’s an expensive joke.”

“You started it!”

He charges into his room, rolls onto the king-sized bed, muttering something about wanting to sleep in peace.

Jump on top of him. Say, “You want to sleep in peace? Or you no longer want to stay married? .”

“Kasarachi, what’s wrong with you? Listen,” The air conditioning hums noisily and he holds your hands apart so your faces are so close, you can feel his warm minty breath on your face. Angry and warm. “What do you really want?”

Take in the lines around his tired eyes. Sigh, say, “Kene, I had an abortion when I was eighteen.” Pause to take in his wincing noises. The vent of the air conditioner grunts and heaves like an old man. “And when we were having problems conceiving, I thought we were being punished for something I’d done.”

His grip slackens around your fingers.

Sit up, say, “Each time I got my period, I felt like a hodgepodge of barren organs.” Let the tears roll down your cheeks and drop on his unshaven chin.

But it’s not the abortion that you regret; you couldn’t have done otherwise. You just wish you had buried the twenty-week-old fetus. You don’t have the words to explain this conviction. Also, part of you fears he’ll judge you for yearning to bury your dead babies, for wanting to get closure.

So you let him stare at you, his eyebrows arched; corrugated lines etched on his forehead.

When sweat begins to pool under your arms, roll on to the bed and say,

“It’s okay if you decide to quit the marriage for good.”

Outside, a neighbor’s dog growls and whimpers. Kene clears his throat.

“Kasarachi, our marriage died when Zara died,”

A strong wind rattles the blinds, slips into the room through the chinks in the windowpanes. Goosebumps cover your skin, not from the cold, but from the dread of abandonment. And yet, you look straight into his eyes and dare him to divorce you.

“But,” Kene says slowly, “but we can start over if you want.”

Cry. Say: “Why? You don’t even bloody love me!”

“Of course, I bloody love you. Do you want me to shout from the top of Mount Kilimanjaro?” He bear-hugs you and grabs a chunk of your hair, until your wig comes off.

Your lunch of spiced roasted meat and juice slowly make their way up from your gut onto your throat. Hurry into the toilet and retch. When Kene comes in, let him hold back your hair while you empty your gut.

“We can start over,” you say, “But I won’t share you with anyone.”

Just as you look up from the toilet bowl, he pulls the lever on the water cistern, and says, “Likewise.”

Wipe your mouth with a paper towel. Say: “Really? And what about Ify? Is your breakup final?”

It’s almost midnight; not a good time to open the ex-files. And yet, Kene indulges you, says:

“What about her?”

“What. About. Her?”

The water cistern quietens. All you can hear is your pounding heart, his heavy breathing.

“Kasarachi, I don’t want her. If I did, I wouldn’t be here.”

Saunter off to your room, leave the door ajar. Don’t cry in excitement as he drags his pillow, his toothbrush and his box of underwear into the master bedroom you once shared.

X

A windy Monday morning. Cumulus clouds block the sun. Move the aquarium to the living room to make room for Kene’s bags.

Drive to work. Avoid the Principal. Offer walnuts to the students who come for counseling. Shift papers around the office desk until the closing bell rings.

Drive to the flea market, humming gratefully for the calm of the post-lockdown, rain cooled atmosphere. On the drive back home, you see a long-limbed dreadlocked man at the tail of Miniokoro bridge handing over a wad of notes to a roadside artist. Slam on your breaks and reverse your car, looking out the window to take in the silky kinkiness of his dreadlocks, his oily ebony-complexioned face. His long, strong diver’s arms lift three sheathed paintings into the backseat of the SUV whose lavender scented seats you remember so well. Is It Really Constantine? Four and a half years have passed since you last saw him, but you’ll recognize those umber locs, anywhere. That stubborn chin, too. It’s him all right, albeit with a rounder tummy. Yet still here, unaware that he fathered a child who died a month ago. He deserves to know about Zara, you think as your car turns full circle at Rumuobiakani roundabout. You can just tell him and be done with it.

Park your car on the Miniokoro Bridge, a few feet in front of him. Hop out of your car and watch Constantine slamming shut the back door and opening the driver’s door. Your eyes lock. For two seconds. You’re sure because your heart skips two beats. You open your mouth to speak to this man who is both familiar and unfamiliar to you. Staring into his eyes, you feel a weight on your chest, like the morning Zara was buried. What you want more than anything is to feel his diver’s arms around you; to hear him promise to make a water baby shrine for Zara. But he just stares at you, perplexed. Look down at his leather shoes. Wince from the pain of yearning for things you can never have.

Hop into your car and drive homewards, peeking into your rearview mirror to watch him scratch the worry lines on his brow. His mouth hangs agape and for a moment, you wonder if he’s howling your name. But your name doesn’t start with an ‘O’, you think as you watch his poised, unconstrained figure grow smaller and smaller, narrowing into a dot that disappears when you swerve into Woji Junction. As your car halts at the legendary Woji traffic, bang your forehead on the steering wheel until the traffic eases up and your car accelerates past the redundant train track. How naïve of you to think that a conversation about the three-and-a-half-year-old Zara would roll off your tongues as easily as your discussion about coral reef triangles and deep-sea diving and water baby shrines?

Nothing will prepare you for the sight of Zara’s school bus parked beside the house. Clean your eyes to be doubly sure you hadn’t imagined Constantine on that Miniokoro bridge and that you aren’t, in fact, imagining the proprietress and the tiny pre-school children who have accompanied her to your home.

Squirt sanitizer onto your hands. Think: Oh God, they’re too young to be paying condolences.

Your husband has served the loaf of Madeira cake from the fridge. And oh, Kene served zobo juice from the freezer. Grab the bread knife from the tray and cut yourself a wedge.

Sit and place your cake on Kene’s saucer. When the proprietress perches beside you and holds your hand, inhale the lavender fragrance of her expensive perfume and smile politely. The first day she met Zara, she had said: “Bright eyes. Can she model for BC International School? Her beautiful face will light up the school’s billboard.” The picture is on a billboard somewhere on Port Harcourt city’s expressway, but you haven’t seen it. You never will. Now, the proprietress says, “Is it okay? Do you want us to take it down?” And you shake your head and say, “No, don’t. Zara will like it up there.”

Stand up when the kids finish their food. Listen to them croon Abide with me in an off-key fashion. It takes you a while to make out the tune. Sway gently, sing along and think, life’s journey is confusing as hell, but full of new beginnings. There’s no fight left in you and your sorrows are forgotten bundles scattered about the abandoned battlefield of life. Savor your husband’s breath on your neck as he leans behind and holds you, his voice blending nicely with the children’s. Smile. Remember: every reef is shaped by the waves and storms and heat it encounters. Acknowledge that you will never get over this loss, and that you don’t have to.

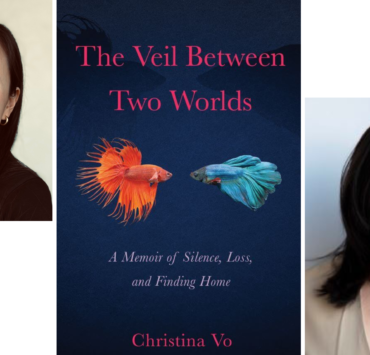

Chioma Iwunze-Ibiam, an MFA student in Cornell University's Creative Writing program, writes fiction that explores the convergence of fate and freewill. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Asterix Journal, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, Flash Fiction Press, Fiction 365, Ebedi Review Anthology and elsewhere. She lives in Ithaca, NY. You can connect with her via twitter @ChiomaIwunze_