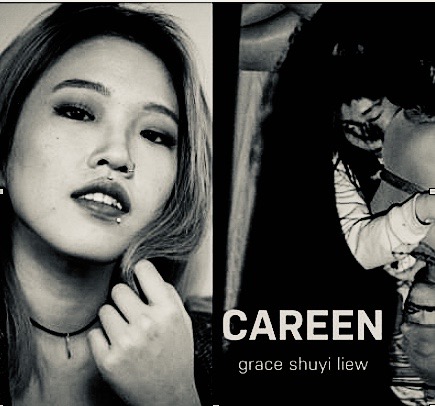

Writing about the musician Mitski, Jia Tolentino argues that, “there is a notion, informed by lasting preconceptions about women artists, that Mitski is revealing more of herself personally with every album when, in fact, she’s revealing more of herself musically, which is not at all the same project.” This “preconception” about women artists, that they are always confessional, that their art is only about the self, is an enduring fiction, part of a long conversation about women and art that Grace Shuyi Liew’s Careen enters with urgent clarity.

There are at least two troubling ideas that come along with this notion that women’s art is always about disclosing the self. The first is that this notion is often trotted out in order to assert that the self, especially the self marked by gender, race, queerness, disability, and so on, is an illegitimate subject for art. The second is that this idea invites a willful misreading of the art, made by many women, that is not about revealing a coherent, unified narrative of the self, but is about exploding that notion.

Tolentino, arguing that Mitski falls into this latter category, goes on to say that on Mitski’s earlier albums, “she seemed to treat self-exposure as a readily available tool, almost a red herring.” In Careen, Grace Shuyi Liew similarly both uses and is critical of this “tool” of self-exposure. In the opening poem, “What Does It Mean to be Durational, not Eternal?” Liew writes, of white lovers, “always when I lift my shirt to reveal / my private galaxy of / bruises / they all cum immediately.” This moment points to the hunger of white audiences to consume racialized and gendered suffering, often under the guise of “learning,” but also, as Liew implies, for their own gratification.

While Liew is critical of those who consume the suffering of others, and while bruises can be markers of harm, the speakers in this book often desire pain, find pleasure in it. Earlier in the same poem: “I want / a beating, want to welt / backward into small openings all over / my skin asking / to be filled.” In a poem near the end of the book, a speaker says, “sometimes / gentleness is utterly optional, how / above the safety of burnished touch / I just want an unwinding so thorough its centrifugal force cannot / be located.”

From this opening poem on, then, Careen launches us into a web of sticky questions: What is pain good for? What to do with a body desiring pain? What to do when pain moves outside the individual body, becomes collective, social, political? What are the risks of revealing one’s pain as a political strategy? In Liew’s words: “Who regards you as liberation // Why do they offer to wipe your face?”

From here, the book gets stickier, offering only uneasy answers to the questions it raises about desire, the self, gender, race. There are moments of urgent clarity, but they always shift and are troubled and re-troubled. The complexity of ideas in the book is mirrored in the way it spools out in a range of forms and modes. Sometimes direct, prosaic, sometimes opaquely lyric. There are linebroken poems that spill on for pages. There are prose poems in boxes, prose lines unbounded. Forms contain and then rupture. A structure organizes but refuses to cohere. The book swings from sequences to shards and back again.

This happens on a micro-level too, the language swerving. A reading offers itself up, tempting, and then careens away. Here is an instance of this, fom “Part I” of “Outgrowth of Contingent Nations”:

You are gonna be okay you say (closed in by bodies) (imaginary pangs) as you familiarize yourself with the facts of your dislocation. You were never clean: your denouncements have always been (mis-)taken as unhinged (orbits of a soft mind). Not that you didn’t earnestly imagine pleasure at every chance (fumbling at your own body) (an avatar made swollen by a grimy appetite) (pliant tongues lapping through a chest opening). You lie spreadeagle and through your teeth to pacify (/investigate) movements that reverberate. (Awaiting the day all your fingers end up inside yourself.)

Even as these sentences suggest the declarative, they swerve away into parentheticals, discursive asides and restatements. The language is at once precise and evasive.

Here and elsewhere voracious desires simmer: “(Awaiting the day all your fingers end up inside yourself).” But I’m left with more questions: Is the speaker voracious? Or rather, am I, the “you”? Do I desire the speaker or do I feel myself in its hungry “you”s and “I”s who desire and are desired, who fuck and are fucked, in a flickering pattern of exposure and concealment across these pages?

Desire, though, is not the same as pleasure. Desire, Liew reminds us, is not about satiation, but is an animating force, driving one outward, elsewhere, onward: “A circle of desire digging from inside another bigger circle is predetermined to forage ceaselessly until it encounters a warm opening, only to mistake it for recognition.”

The book itself seems to “forage ceaselessly,” particularly in “Displaced, Replaced,” which consists of a sequence of essay-like prose pieces describing time spent in Berlin, New York, “(Between) Los Angeles & Other Coasts,” and finally Kuala Lumpur. Here the speaker is located in geography as she describes a series of bodily, emotional, racial dislocations.

In Berlin, the speaker suffers a swollen top lip whose infection is a “white pus,” “wet and persistent” and she careens, dislocated, among white and male bookstores, white women and their projections. In New York, the speaker arrives with a purpose: to see old friends. But she ends up “incoherent and sobbing: I am not one of you. I cannot say why. I speak all the ways you ask of me, but this one I cannot say why.” The dislocation here is social and geographic, revealing a desire for recognition and belonging.

Liew points to the ways that desires, sexual and otherwise, are shaped by outside forces: by gender, race, colonization. In “(Between) Los Angeles & Other Coasts” the speaker attempts to buy a condom in French, an exchange reduced to a comedy of errors involving a soup ladle. After this come these devastating lines: “After all the ready lies you have told, it’s hard to keep track of what you actually want, where you hope to go. You get used to this hardness until your voice scabs over.”

There is some relief in “Kuala Lumpur,” “The home state” that “nurses a thirst for revenge that rages through your twenties.” It is not an idealized homecoming, but it is a space that feels different from the white European and American landscapes of much of the rest of the book: “Anywhere less, you live a separate life unprotected by irony. Your dreams are exposés that allow no distance between yourself and every single felt emotion.” Here, desire appears again, this time turned inwards towards the self: “You will want yourself all over again, once you diminish the size of your own warnings.”

Beneath these desires for belonging, recognition, pleasure, pain lies a political desire. The book imagines a world free of white supremacist, colonial, misogynist violence, a world where the systems of relation and of power are re-oriented towards care, community, solidarity.

In “The Uses of Lyricism”, the speaker makes explicit these desires through considering the way artists of color, particularly James Baldwin, are commodified and sold as symbols of art in a way that attempts to contain these artists’ political potential. The poem discusses Baldwin’s former house being torn down “to make way for luxury villas they will name / ‘Le Jardin des Arts’…[which] will carry luminous myths / of Baldwin the artist, stripped of any locatable color / or weight.”

Liew points to these artists of color, the art that they’ve made, and their relationships to each other as valuable sources of knowledge for building a different world. The poem discusses Billie Holiday’s heroin use, and Miles Davis’ defense of what others see as his complicity in her addiction. Liew sees in this defense a “buoyant footpath,” (79), one perhaps of artists of color caring for each other, even if this care might look like harm, even if this care can only for now be harm reduction against the harms done by violent social structures.

In this poem, Liew also points to the ways that these structures of imperial, colonial violence are maintained only through producing their own myths, their fictions, their lies that work hard to look like truths but in so doing expose their own architecture:

The task of creating representations

of reality drove a quivering stake into the ground that day,

and have since doubled as an abandoned

pilgrimage site for theorists who make grand claims

about utility or victory or hardwired instincts, as in

about utility or victory or hardwired instincts, as in

every time I walk my dog toward the Mississippi

levee I have to pass a shiny plaque that reads

FREEDOM ISN’T FREE. Who knew violence

struggled to believe in its own surety and sought

for comfort too?

Exposure, then, can mean revealing a vulnerability that is not personal, as in the exposures of sex, but strategic, as in exposing the vulnerabilities of a power structure, the weak point that might bring it to its knees.

There is hope here, or not hope necessarily, but a belief in possibility, for things to be otherwise, for a future and in fact a present that already live alongside history, in its untouchable atmosphere, waiting to be uncovered, revealed, as in the last lines of the book: “Today’s heaviness is already thinning out, / ready to fall again as rain.”

Grace Shuyi Liew’s work has appeared in West Branch, Black Warrior Review, Kenyon Review, cream city review, PANK, The Wanderer, and elsewhere. She is a Watering Hole fellow. Her other honors include the Lucille Clifton Poetry Fellowship from Squaw Valley Community of Writers, Aspen Summer Words scholarship, resident writer at Can Serrat in Barcelona, resident at Agora Affect, Vancouver Poetry House’s “10 Best Poems of 2016,” Ahsahta Press Chapbook Prize 2016, and others. She holds a BA in Philosophy from Hamilton College, and MFA in Creative Writing from Northern Arizona University. She is a Contributing Editor for Waxwing.

Liew’s book, Careen (Noemi Press, 2019) is available for purchase.

Stephanie Cawley is a poet from southern New Jersey. She is the author of My Heart But Not My Heart (Slope Editions, 2020), winner of the Slope Book Prize chosen by Solmaz Sharif, and Animal Mineral (forthcoming YesYes Books, 2021), as well as the chapbook A Wilderness (Gazing Grain, 2019). She works at Stockton University.