Chee Wang Ng uses the leitmotif of a bowl of rice to address Chinese Diaspora identity. He recently sat down with guest editor Ari Ariel in New York to talk about how food impacts his work.

[sliders id=”246″]AA: How important is food to your work?

CWN: It’s essential. And even though I do specifically Chinese themes, my point by doing it, especially in NY where we’re a cosmopolitan society, is to think about identity. When you think about yourself it’s also related to the other. That’s the point. It’s the idiosyncrasy of the thing. That’s why in my first art catalogue I had chosen the title Eaten Your Fill of Rice? Basically that is an opening greeting, very traditional, very vernacular, very local. When you meet someone instead of saying hello you say ‘have you eaten your rice’, because if you’ve had your rice it’s a good day. That is how essential it is. What is identity? It is the differences. What is different, for you, makes you who you are. But at the same time what bonds everybody is humanity. So what you have to figure out is that essential-ness. Rice is also essential for security, and its importance is growing. Two or three years ago bad weather created a shortage of rice and suddenly the UN was inundated with complaints, because rice is the cheapest growing crop to feed the poor population, so if there is a shortage world security is threatened.

AA: How did you decide to work on rice specifically?

CWN: It comes down to basically comparing and contrasting experience. I am always trying to find the distinctiveness of a thing. Where I’m from, in Malaysia, you always go out with people like you but when I came to New York, as a Chinese guy, I met Chinese people from all over the world and half the time none of us could even talk to each other even though we were all Chinese, because some people speak mandarin, I speak Cantonese and others speak in local dialects. It’s difficult, and half the time because you are in multicultural environments, you end up speaking English. But guess what, no matter what, you end up really happy going to dinner, and all of us eat rice. So that sort of kicked off the idea of what’s common among us. I saw that commonality, but at the same time, when you’re away form home you are also able to see what is distinctive – you’re distant enough to compare and contrast. When I started doing it, and perhaps this is typically New York, I thought about doing something pan-Asian or pan-East Asian, but then I realized that I didn’t know enough about Japanese culture or Korean culture, and decided it was best to do what I know.

AA: Some theorist and historians believe that national cuisines, like Chinese or Italian, which are created out of distinct regional food practices, are formed out from the experience of migration. Has your relationship to Chinese food changed at all with you own migration?

CWN: Yes, think about another example. I think you will feel that this is relevant in terms of diaspora. In terms of culture, if you think of culture in terms of scientific culture – remember in high school, your petri dish? If you take a culture from an original source and transpose it to a different environment, that transposed culture will stay true to its original form longer than the culture in the original petri dish. The reason is that when you transpose a culture to a new environment it has to spend time and energy fighting the new environment and it creates its own environment, and it will try to maintain its own characteristics. On the other hand, the culture in the original source, because it just basically maintains itself and transforms slowly, because it doesn’t need that energy to fight it a foreign environment. The same thing happens in the culture of language. For example in Hong Kong, its such a transient place, when someone speaks to me in Cantonese, I can easily identify how old they are, because Hong Kong is such a cosmopolitan culture that people there borrow a lot of words, not in the written form but in the colloquial form, so when they say ‘i-pod…’ you know exactly what time period it is. Sometimes, for example, I would watch the TV series, local productions – and I speak Cantonese, and they’re in Cantonese, but I don’t understand half the things they are saying. That is how culture changes.

AA: How does the culture of language impact your work?

CWN: It’s very important. I’m trilingual. My mother tongue is Cantonese, but in school I learned English, and since I grew up in Malaysia we learned Malay as well. Chinese is a very colloquial language, based on sounds, so I pick up on the sounds of words, the sound of it, and that’s why many of the series I do have the literal with the visual. Wording is very important to me because to me it creates a different sensation.

AA: How do you choose the text and titles that accompany your art?

CWN: Actually for me, I’m a visual person, the titles are the most difficult part.

AA: Because of the difficulty of describing your visual work in words?

CWN: No, because if you see the Chinese words, these are very traditional Chinese forms. There are always four characters in naming. Some of my titles are using proverbs and some of them idioms, so it’s a very traditional form, but how can you translate them? Some of them are literally translated but some of them can’t be, so you have to transpose them. You can’t do it word for word. But in the case of the title of this series (Eaten Your Fill of Rice?) I purposely named it in pidgin English because it’s about identity. I wanted to stress that distinctiveness of it.

AA: Let’s talk about some of the individual pieces.

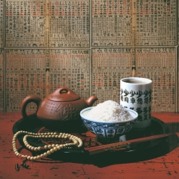

CWN: For this one [“Mindful of the Seven Emotion”] I took the old masters, the Flemish, the Dutch painting, the styling of it. But at the same time the subject matter is totally Asian. The whole point about it is that, to me the bowl of rice is essential, and the outside is like dressing. And you can dress anyway you want but your identity is still what you are.

AA: How did you choose what to include?

CWN: I start with the bowl, the bowl is what leads me. Something about the shape and the color of the bowl speaks to me. So once I have that, I build upon it. Initially I started to collect all different color bowls, and then it occurred to me that I was missing something, I hadn’t bought the white ones, so then I started to collect white bowls. Right now I have between three to five thousand white bowls.

AA: What was the thought process behind the bowl of rice on top of the soup cans. Have you been influenced by Warhol?

CWN: Warhol is essentially pop. I wanted to do something, for example like the piece inspired by the Flemish masters – I was inspired by the old masters in terms of styling – I wanted to do a riff on pop art also. And who else can you think of but Warhol. Campbell started using the old style labels for chicken noodle and tomato, for some of the other soups they fancied them up more. So I started collecting them, and I didn’t know what to do with them, and suddenly it occurred to me that the cans are metal- so I realized that I needed a metal bowl. To me everything I do has to interlock or complete a set. You need a hook. And to me my hook was the cans. Some of the mainland Chinese artist who borrow from the contemporary artists, they just copy. So I wanted to be sure to do it within a context. I decided to place the metal bowl on top of the cans, and my rationale was that the metal rice bowl in the Chinese idiom means that you have a steady income – a steady job. Typically, bowls that are made of porcelain, they break. Also, in the Chinese colloquial language, ‘looking for rice’ means you are making a living. So livelihood and rice are closely connected. Especially during the Mao era, they said ‘you have an iron rice bowl’, meaning you are working for the government or the military, meaning your income is steady. And the words Andy Warhol, if you translate them into Chinese characters, one of the characters of the word ‘andy’ also means peace. Meaning you have no worries, you have peace. And in Chinese, one of the words for ‘no worries’ means griefless peace.

AA: If feels like you are using rice to insert yourself into all these different contexts.

CWN: One of the things artists always do, we pay homage to the old masters or use them as a base, because art is a dialogue. The way some of the mainland Chinese artists approach western art in this context is very peculiar, since they are less aware of the proper context and art history. But the great artists, because they have less baggage, have taken it off on a trajectory. In my case, having both the Eastern and Western art history gives me a great base to build upon. In the case of my piece Griefless Peace I said, I know Andy Warhol, I know the history, I know the context, but how can I do it with reference to everything that he’s done while at the same time putting my little touch on it. When I finally got it, it was one of those moments when you think ‘why didn’t I think of that sooner’. It took me three years.

AA: So you had the cans for 3 years before you knew what to do with them?

CWN: It’s like the bowls. Most of the time when I buy the bowls I have no idea what I am going to do with them. I play with ideas and see what clicks for me.

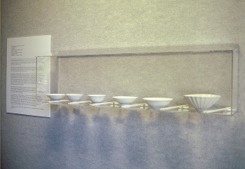

AA: Can you tell me a bit about your installations?

CWN: One of the things about culture is that there is always a bit of bigotry when you point out something about someone else’s culture, but at the same time you can always poke fun at yourself. So the title of one of my installations, for example, is 100 China(s): All Chinese Looks Alike…, I can say that, but if you said that I’d probably be angry. The space for this installation was perfect. It was long corridor, and I lined up 99 bowls and each bowl had an army tag below it listing its country of origin and pair of chopsticks. But there were only 99, not 100, and again the reason is connected to culture. My work is based on traditions, and in Chinese tradition honor is very important. My idea was that the viewer would fulfill the honorable position of the hundredth bowl, so you complete the whole set. My work is very layered and post modern. We are living in the world, so how do we identify? Army tags are a bit hard to read, but I liked the idea that you couldn’t really read them. The whole point was that, yeah ‘Chinese look alike’, yeah right, look at the bowls – china, Chinese, but they’re all different, from different countries and the whole idea is about Diaspora and about origins.

AA: What about the barbed wire installation?

CWN: I had all these bowl and I had to figure out how to use them. When I do shows I ship the bowls and sometimes they break. But they feel personal to me, I can’t replace them and I don’t have the heart to throw them away. And when the idea for this installation Five Elements Mountain of Bowls of Rice came about I realized that I could use them. The whole idea was to make five mountains of bowls. I used huge bowls, small bowls – all different sizes and shades so that I could compare and contrast the variations. And instead of just making the mountains, I placed the broken bowls to the sides, as if they had just fallen. Those got more attention then any of the others. Somehow I’d always wanted to use barbed wire. The whole idea of barbed wire makes everybody scared. My curator was really good- I suggested using barbed wire, but she was concerned about children coming to the gallery and their safety. So it’s not actually barbed wire, it’s made from strips of leather. My whole idea for this piece was that it would be ying and yang – the bowls are precious and I wanted something else, like barbed wire that conflicts with them. I needed that tension.

AA: This issue of Vandal is about food and movement, and one of the things I thought was most interesting about this piece was the way the barbed wire restricts movement.

CWN: The whole thing about food is that it’s something you want to approach, but the barbed wire is a defensive element. And actually the whole reason I wanted to use barbed wire was because I didn’t want anyone to steal the bowls. The piece got very interesting reactions. And because it was an installation I got to stand back and watch people’s reactions. Most of the time I don’t know what my viewers are thinking. This is a huge piece, its about 10’ by 10’ so you have to get close enough to it to look through the barbed wire. People would walk to it, but then when they arrived they saw the barbwire, and their personal defensive systems kicked in, so they’d approach it but they never got really close. And, of course, they didn’t know it was fake, it looks real. They got close to it, they’d look at the different variations of the white bowls – they are different colors, some more grey, some blue-ish, there are about 600 bowls there. I placed some of them so it looked like they were about to fall. That was the element of movement. So they had to get close enough to look through the barbed wire, and then they would linger there, but quickly get paranoid because they saw a broken bowl on the floor. That was really cool. They would had spent about two minutes, which is a lot, some items just get a few seconds of attention. But after two minutes or so they would make a quick 180 degree turn and walk away. You know why – because of the barbwire, to get away from it. I was elated! To me, that is why I do, what I do. It is really an interesting way to observe and study people. I see what people like, what they want to see and touch. As an artist you are always planting a seed to instigate. I feel like I’ve done my part if I get a reaction. One thing I’m proud of in my work is that I investigate the whole richness of life and culture. That is what art is all about – it’s about culture. Sometimes I talk about art, sometimes sex, sometimes Confucianism, it’s culture, every aspect of it. I have a theme, a motif – a bowl of rice. But the bowl of rice, after you see the work, after a while the bowl of rice is not even the subject anymore, it is everything around it. Think about it.

AA: So the bowl of rice is constant and everything around it is changing. That’s another interesting kind of movement.

CWN: That is how I approached the series. I started in the late 80s and I knew exactly what size I wanted. All these photographs are 4’ by 4’. I didn’t want them to be supersized. I think that photography is a medium that a lot of people don’t understand. Think about photography 100 years ago, when the photograph was new – it was very personal, you put it in lockets, it was part of a one to one relationship. But with the advance of technology and digital cameras, our relationship to photography has changed radically. But one thing that hasn’t changed, if your really conscious of it, is our visual field, it is always 60 degrees. So I really want to shoot just the right size, I put in many little details, and everything is super sharp, so that your eyes linger. You take in the overall view, and then you scan. I’m always trying to steal those ten seconds from you when you scan the photograph. And my work is always better as a series, when you see multiple. And I’m always trying to get the viewer to think about what you’re seeing. It’s my inside joke. You know, rice, rice, rice –after a while you’re not seeing rice anymore. Hopefully your perception changes, from the first moment to the longer duration. It is a dialogue. And then I provide the title and my explanation to help qualify the image in your mind. And I think it becomes a stronger image than when you first see it.

AA: So you want to prevent the viewer from looking at your work passively.

CWN: Right, because I think of it as conceptual photography, it is not just a pretty picture.