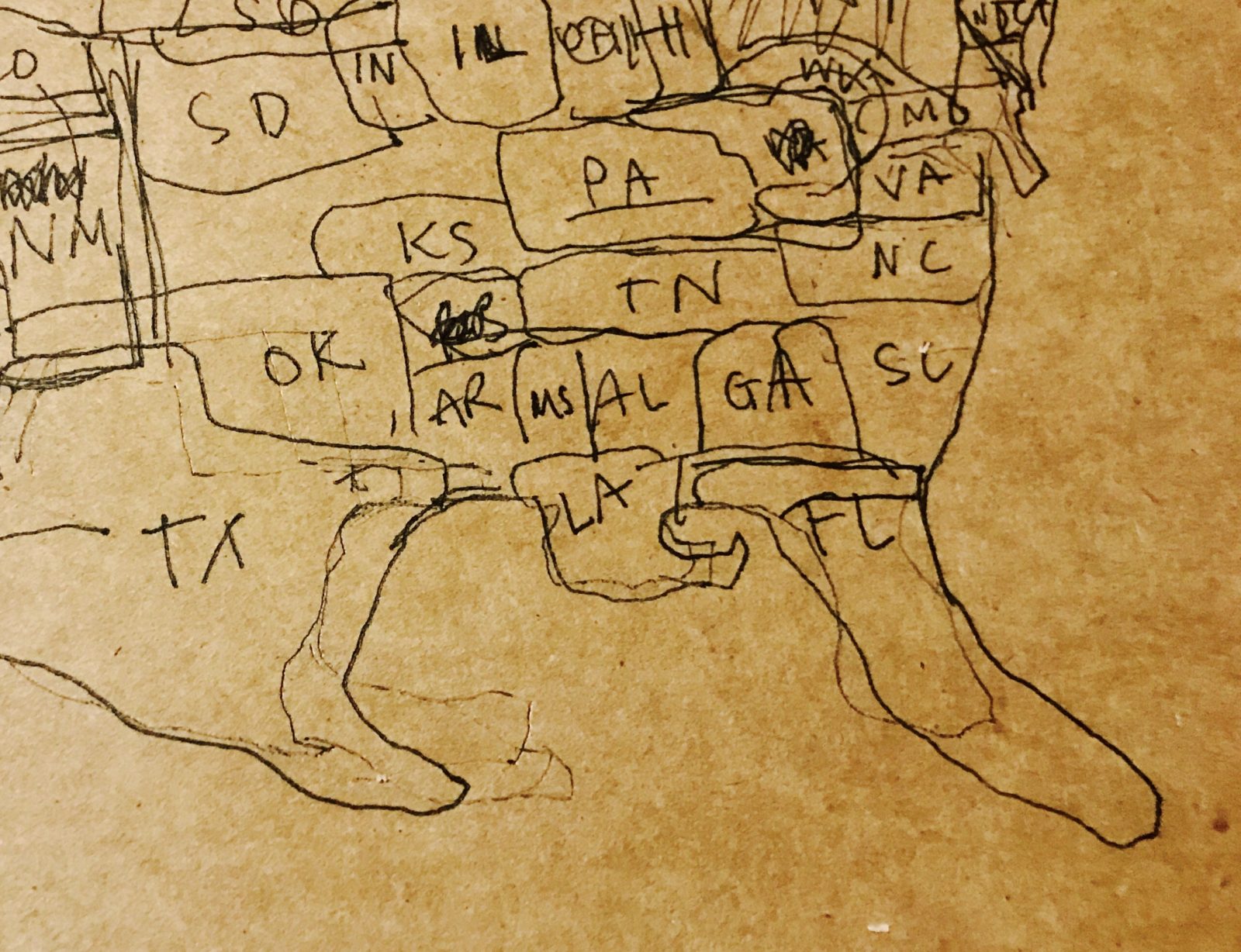

We began our conversation with Sandra Cisneros drawing our own personal maps of the United States. Drawing jump-started our conversation about latinidad, place, writing, privilege, power, and activism. In the end we journeyed together in conversation remembering and thinking through how we work and continue to work as Latina/o creatives and scholars. Also in attendance: Angie Cruz, Clarissa A. León, Armando García, Adriana E. Ramírez, Elizabeth Rodriguez Fielder, Tanya Shirazi and Angela Velez.

Angie Cruz: One of the reasons we started Aster(ix) was in response to the question, who is publishing women writers of color? Through my work with the journal I’ve realized how many writers of color, even the more established writers, are having a difficult time placing their work, especially when the work is not performing their identity politics. But also we have found that women of color don’t always submit their work. They need to be solicited.

Sandra Cisneros: I don’t send my poems out unless someone asks me.

AC: Me neither, and this is true for many women writers I know. So then people are like, what happened to her? Is she publishing? That’s one of the reasons we started Aster(ix). To find each other. To put our works in conversation with each other.

SC: We had a women of color journal and it created a place for Cherrie Moraga, Ana Castillo, me, and others: Third Women Press. It published us. It didn’t get support from the university because Norma Alarcon didn’t want it to be controlled by them. But that’s how we found each other. And it’s really important.

AC: I was really inspired by that conversation we had many years ago, when we spent a day together in Torino. You said one of your inspirations to found Macondo was your commitment to push writers to make their very best work.

SC: The reason I also created it was because I thought that we needed those networks. So many of the Macondistas continue to edit each other and connect. They don’t feel necessarily that they have to keep supporting Macondo because they have their own community. But there’s younger people coming up. It needs to continue. We still need that network, that zócalo where to meet.

AC: A lot of writers that I know, especially those that are sending their work out, feel if their work doesn’t legibly appear to be Latino/a—it has a more difficult time getting placed. What do you think?

Adriana E. Ramírez: I think it’s less so in nonfiction

AC: But what Latino/a in nonfiction that is published isn’t writing about a Latin-American/ latino/a problem?

AER: It depends on who you are. If a Latino/a historian is writing about the history of the Apache, I don’t think that’s necessarily performing your identity. I think it’s a unique perspective of a historical thing. I can’t divorce myself from who I am. I look in the mirror and see the nopal and everything. You are who you are. Even the way I use language, the aphorisms that pop up. Even “Cero a la izquierda,” doesn’t even sound right in English. “Zeros to the left”?

AC: I do think the dearth of Latina writers getting published each year makes creating spaces such as Macondo and Aster(ix) an urgent matter, even if neither of our activist efforts are by no means exclusively Latino/a. What I also realized is how many writers, because they are activists, mothers, etc., don’t have the time and space to write. I think we desperately need writing residencies, where we’re asked to do nothing but our creative work.

SC: But don’t you think too that some part of not making the time to write is also that we make ourselves too available? Regarding activism, I think when we rescue, it’s because we’re rescuing some part of ourselves too. That’s what a therapist would tell you. You’re rescuing, but you’re rescuing yourself too. Where you don’t feel you do enough, or you feel guilty because of your success or whatever it is. That’s why I started the foundation. I felt guilty there wasn’t more success for others.

AC: But, Sandra, if you hadn’t started Macondo, who was going to do it?

SC: I also did it because unless I invited them, I couldn’t get the writers I wanted to see to come to San Antonio. I needed my oxygen supply and my water supply.

AC: But you also changed so many people’s lives because of Macondo. Like VONA Voices, and Cave Canem. Like Toi Derricotte who put a lot of energy into Cave Canem. If she wouldn’t have done it, who would’ve done it? So there’s always that thought too. Not that we should be doing this work forever.

SC: Oh, I think we should do it, and then we should pass the baton. You don’t have to do it your whole life or you don’t have to do it for ten years. I think you can do it for as long as you can do it and once it had a good run somebody else can start something else. I often wonder if we make ourselves too available as women. We have to stop. I did two foundations, and I gave fifty fold. I don’t have to feel like I’m a bad person now.

AC: Do any of you feel a pressure to be activists or give back? If so how?

Tanya Shirazi: I worked in educational outreach for eleven years before I finally decided to fully invest in my creative writing pursuit. I went to grad school in counseling. It was hard to leave those altruistic career spaces—I made close connections with first-generation Latinx undergrads. They are my second family. When I decided to pursue an MFA and leave I felt selfish. In my heart though, I knew it was time to nurture the creative part of me that I had ignored for so long. Sometimes we have to find a balance in how much we give to other people as well as to our craft.

SC: When Ursula K. Leguin turned 60, she went into sanctuary. She calls it sanctuary. She says I can’t. I’m in sanctuary. And that’s what you’ve got to say, ‘I’m in sanctuary.’ When I come out of sanctuary, you can approach me, but don’t tell them when you’re coming out of sanctuary. Never come out of sanctuary. You know, just go into sanctuary and say, ‘Not now, I’m in sanctuary.’

AC: I love it. That’s what I’m going to call it, my sanctuary. It’s like what I used to tell my family when I moved back into my old neighborhood to get out of family commitments; I would say, ‘Estoy estudiando.’ ‘Oh! Estudiando, esta bien!’ ‘Estudiando’ was like the magical word. If I was studying, everyone left me alone.

SC: Yeah, que bueno to have that kind privacy.

Angela Velez: In my house, the only door that locked was the bathroom door.

AC: Yeah, me too. I grew up that way. No privacy.

AV: No one bothered me there — I would just run the bath tub for 30 minutes and lock myself in and read my book. It was the only privacy I could have.

SC: A lot of houses don’t have doors.

AV: And I shared a room anyway, so a door is a privilege.

SC: When I was in middle school we moved to a house where I had the only bedroom with a door in the whole house but I couldn’t close the door because I had a big piece of furniture. The room was really tiny, like only a twin bed could fit in it and a dresser and a little corridor this wide – to get to the bed and open the door. But the furniture was longer than the room and the door couldn’t close because of the furniture. I had a door, but I couldn’t close it. It had to stay open like this much.

![]()

AC: So, I have a question. Some of my writer friends have told me I have to go into ‘sanctuary’ so I can finish my books. They say I am doing too much. So it makes me wonder what do you think is the role of the writer? The responsibility to her community?

SC: You do what you can and then you have to pass the baton on to the people you helped.

AC: So, it should be cyclical.

SC: Yes, yes. You already did your work. You say, I helped you, now you got to pay it back.

AC: What do you think about the new generation of writers?

SC: I don’t know the new generation. Who do you mean?

AC: Like, the younger writers. What do you think?

SC: I don’t know. I don’t know them. I mean, I can’t make generalizations. I just know I like the work that I see coming up. I only know the books that come to my attention, the Macondistas or the people in the Southwest. No sé. You tell me.

AC: Well, do you feel that technology has shifted community building, do you think it’s strengthened it?

SC: I’m very technologically backwards, so I don’t know.

AC: But you’re active on Instagram.

SC: That’s only because my friend Macarena got me to do it. I like taking pictures so it works really well for me. I can’t even type with two thumbs. I type with one index finger. My friends said that we’re going to start evolving and having smaller and smaller thumbs.

![]()

AC: Sandra, you’ve always been so good at creating community. When you were in San Antonio didn’t you meet with other writers and approach them to write together?

SC: When I was in Chicago we would meet in my house, and we would have workshop, and we would meet in cafés like this and just buy a coffee and a croissant and pass manuscripts and write together. We weren’t writing, we were editing. And when I got to San Antonio, and I could afford to donate a workshop week, I started workshop at first at the Guadalupe and then it was in my kitchen table and then it just kind of grew from that

AC: You don’t share your work anymore?

SC: I do share my work. Like my friend, Ruth Behar, edits my essays.

Did you know she’s got a new young adult novel. A first novel.

AV: What’s it called?

SC: Lucky Broken Girl.

AV: There are a lot of young Latino writers who are young adult authors.

It’s really exciting.

SC: It took Ruth sixty years to become a novelist—she always wanted to be a novelist, but she was an anthropologist, and here she was a MacArthur winner, and she was very unhappy because she wanted to be a creative writer and so now she has her first novel and she’s 60. I’m really happy for her.

AV: I worked as a young adult editor for a few years. I worked for a packaging company, so we came up with concepts for books, and we contracted writers to write them. It was called Paper Lantern Lit and they sold books to a number of different publishing houses.

SC: And who were some of your writers?

AV: Probably the biggest book is Rhoda Belleza’s book. It’s a soap opera set in space, and it’s very good But for many of the books I worked on, the focus was on creating high-concept, commercial books, rather than literary fiction.

SC: Well, why can’t you write literary young adult fiction?

AV: Oh, I think you can, but it’s a challenge with a quick turnaround. The literary part takes time and it has to come from the author, and often that’s lost in the rush to publish.

SC: A book I like is called Blood Line by Joe Jimenez. He’s a poet and he did this novel about a young teenager in high school, you know the one who’s always getting kicked out of class for fighting, and his mother isn’t even his mother. His grandmother raises him and it begins with the grandmother having to invite her son who’s like a no-good-bum guy to come back to the house to try and straighten him out and it’s just a beautiful, beautiful book. Beautifully written. I don’t know how long it took him but I think when poets do that crossover from poetry to fiction, they do great jobs.

AC: Who publishes him?

SC: Small presses. I think there’s a lot of good writing coming out of the southwest. Writers that I know from Texas personally. I think the writers that do get published by the larger publishing houses, it’s because they are palatable to a white audience.

AV: I think there can be many goals for something literary.

SC: I think publishers need to give young people the best. Because a young person may not read another book again. The difference between a good book and a great one is just time. Don’t you think? And I think some writing needs another pasadita, another bit of editing. I think a lot of times writers, especially of color…is it Dr. Johnson who said, women writing, it’s not that they write well but that they could write at all. Like a dog walking on its hind legs. Not that it walks well, but that it could walk at all. And I think sometimes editors treat Latino writers not that we can write well, but that we can write at all. And we should not lower ourselves to do work that isn’t better than good and that’s because people expect us to fail. I’ve always felt like people expect women and people of color to fail. So we got to do better than that.

AC: Do you feel that’s true in writing workshops and publishing?

SC: I just feel like we always have to be better than good. You know women have to be better than the guys, and people of color have to be better than mainstream lit. I feel like we got to always be excellent and that difference between good and excellent is time. But a lot of our writers before they came to Macondo were treated with kid gloves in their workshops. Just because they were a person of color. But I like Macondo because you have other people that are your peers that are telling you, this is good. But why can’t you make it great? I know that some of our Macondo writers had to take jobs and do books for hire. But I just think if they had a little more time, and if they could come up with their own concepts then they would do it.

AC: I do agree lots of works could use more time, but as an editor sometimes I get a story and give the writer feedback, and they will ignore my feedback, and publish it somewhere—and they are satisfied with just getting it published. And I say, why did they throw away that story? They’ve already spent a year on it, why not another week? So we are bombarded in general with such mediocrity. To me, publishing mediocre work is another form of pollution. Content pollution.

SC: They’re not honoring their work.

AC: They could have given it another few months and try to take it to the next level, and it would have been better for their career in general.

SC: This is the thing that young writers don’t realize. I’m on the panels giving them awards. I’m on those panels with the other judges that are looking at that manuscript and if you don’t do a good job with that book it’s going to hold you back from getting your next book, or getting an award.So every time you put a book out there that isn’t your best, you’re advertising that you’re not the best. So, what do you want, the money? Or do you want to tell people you’re a half-assed writer? Because that’s what you’re advertising.

AC: Right, because as a judge you need to be able to defend the work.

SC: So that’s the part that the young people don’t get. Every book should be your very best like it’s your last book and the only book you’re going to write in your life and every book should be better than your last one. Because you’re on a trajectory and if you don’t do that, that may be your last book.

AC: But also some writers never take the chance to put their work out. I find that sometimes I hold back, a kind of self censorship, or a thinking of an expectation of what I was supposed to be writing versus what I wanted to write. I always struggle with that. I guess it’s because I’m one of the very few Dominicanas who has been published in English. But also I wasn’t honoring how much I’d changed, and how much I’d grown from the books I had written. I have to trick myself to forget the audience and just write the book.

SC: I think you got to keep the audience out and when you’re thinking about the audience is when you’re either doing the small writing, the writing where you get your agenda out of the way. You have to work so hard to get your agenda out of the way.

AC: And I see so many writers of color that we solicit for Aster(ix) send us work, and I feel this tension in the work, where they are representing culture but also translating their experience to some general unknown audience that almost feels derivative of writing that they’ve read, or they think women of color should be writing. Writers—why are you writing about this? Is this really what you want to write about? But it’s almost like, because that’s all they’ve seen in the context of Latino/a narratives, they’re stuck there. When I did research for Let It Rain Coffee, I was going to the archive in Santo Domingo to look at old newspapers and the archivist there said, don’t make the same mistake that Vargas Llosa did with Feast of the Goat. And I said, What do you mean? “He wrote with his head. That’s not our people!” He said that Llosa’s book was very well researched but you can’t feel anything. His advice: write from your heart.

SC: Yeah, yeah. That’s the challenge. Edit with your head, but write from your heart., I used to tell people, turn this off, turn this on. When you write, write from here. (Taps chest) And then turn this off and turn this on.

AC: Who was it that said, write drunk, edit sober.

SC: Well, I don’t think you should write drunk, because it all sounds good when you’re drunk—but I think you should write sober and edit sober. That is what I would say, and you don’t do them at the same time. Well, I think that when you drink, you’re trying to numb yourself. And when you write, it’s like driving, you have to be as lucid as possible. Also, writing takes up so much energy. You have to sleep. I can’t do it at the end of the day like when I was young.

AC: Last year, I invited Helena Maria Viramontes to do a reading with Mary Gaitskill. Did you know they were born in the same year, came out with their firsts books around the mid 80s? Both of their books were about sexuality and taboo and relationships. I had never thought of them in conversation with each other, but once they were here together, it was interesting to see how different their trajectories were. Gaitskill’s book was a literary sensation, framed as a new feminist voice that was changing the literary landscape, and Viramontes’ book, when I looked at the reviews, they were all modeling some kind of sociological study of the Chicano community. It was very marginalized in comparison to the way Gaitskill blew up the literary scene. In the end, the trajectory of Helena and Mary—so different. Very different doors opened for each of them. But also while Viramontes was visiting Pittsburgh, I invited Toi Derricotte to dinner and in our conversation, Viramontes shared how her early influences were African American writers. This is also true for me—I was influenced by the slave narratives, contemporary black writers, etc, like Morrison, Baldwin, etc. And I realized just how many Latina writers I know are influenced by African American literature. So out of curiosity I have made it a point to ask non Latino/a writers what Latino/a writers do they read? They often can’t name Latino/a writers writing in English. Latin American writers yes, in translation. Unless of course it’s Junot Díaz or you. Does anyone have any thoughts on this?

Elizabeth Rodriguez Fielder: It’s definitely not compatible with the history of activism between the two groups—between Black and Latinx groups. There has always been a history of activism. Not that it doesn’t have its problems. There’s always been this shared intensive struggle. I think that it really has a lot to do with academic disciplines that everything gets brought into if you’re bringing some things into the university space they have departments that are in different floors and different places.

SC: I grew up in Chicago, a very multicultural city. I was influenced by immigrant writers, working-class writers. I hate to use the word minority, because we are the majority in the world. I was influenced by writers of color. I was influence by all of the above. I’m still influenced by writers that are somehow off the beaten path. I was very influenced by the Latino boom. I never like reading who’s on the bestseller list. I’m kind of a snob like that. If everyone likes it I don’t like it. You know how they do those little surveys? Those little pies? I’m always the 4%.

What I need isn’t going to be on the bestseller list. I was looking for somebody more new and obscure. I’m still off the beaten path as far as writers I like.

AC: I’m not saying this as a critique to any writer, but there is some writing that crosses over that is written to Middle America and then there is Latino/a writing that is having a more internal conversation. I think of Toni Morrison when she was an editor and she was interested in writers who were…not like Ralph Ellison. She was like, “invisible to whom?” She was interested in Toni Cade Bambara and Gayl Jones. She was interested in these writers that were writing to her. I think that there’s a lot of writers in the Southwest that are writing to each other and not to those folks in the white Middle America.

ERF: I think that’s a large aspect of minority literature in Black literature, Latino literature: That there’s a difference between writing to the white audience and writing to one’s own community.

SC: I think we shouldn’t say color, we should say class. That’s very important. I identify a lot with some white writers that are working class and not always with writers of color that aren’t working class. That’s an important distinction.

AER: There’s no phrase that I love more than “The U.S. has a class problem that it calls a race problem and Latin America has a race problem that it calls a class problem.” I think there’s a danger in oppression Olympics—who’s had it worse. Like, should Black readers be reading Latino writers, who is owed what? I am very wary of taking two groups that are oppressed and in some way rhetorically pitting them against each other.

AC: But there is an invisibility that comes with the system.

AER: I agree. I would say two things. One, I think it is interesting the amount of Latinos who are killed by police that aren’t reported on, and aren’t reported the same way. You can see the Black community has mobilized and there’s a lot more of a core identity. I think the problem is that we assume that there’s a pan-Latino identity and I don’t think there is. As somebody who is Mexican and Colombian, it’s a different identity than when I’m talking to someone who is Puerto Rican. Certainly, there’s also a class divide. El español que yo tengo es un español que definitivamente marca mi educación, y de dónde soy, y el acento lo dice. The fact that I don’t have an accent in English either, speaks to certain privilege. It’s tough to negotiate all that. Second, I want to ask you Sandra—Do you think your writing is palatable?

SC: I don’t know, I’m not a white person.

AC: Your writing is read in a certain way, but if you read it closely it’s really subversive and radical in a way that it’s not palatable if people read it with all the subtext.

SC: There’s a lot of subtext and I always tell the kids when I visit schools and talk to them about House [on Mango Street]. I tell them you know more than your teacher about this book. You are the authority. Why is that bike for sale that the girls buy? Why does Tito have to get rid of it so fast? And they know that’s a hot bike. It’s stolen. But it’s not in the text. The kids know. A lot of little things like that, they aren’t spelled out for someone unless you’re from the barrio or a community like The House on Mango Street. I always tell the kids, you know more than the teacher.

AC: I’m curious for those of you who represent a younger generation of writers, up and coming, what does the literary landscape look like to you?

AV: I think it’s a little different for me. I’m really interested in writing young adult literature. There’s a strong push right now for diverse books. There are visible leaders that are putting pressure on editors. People are supportive and asking for new kinds of narratives. That feels very exciting. I’ve seen my friends get books published and their books do really well, and they are writers of color and who are being read cross-culturally. But looking at the adult world of fiction, that looks scary and intimidating.

TS: This is my first year in the MFA program, it’s my first semester. For one of my classes, I wanted to write a paper on what is is to be considered an “Authentic American.” To me, it’s the angle that children of immigrants have to reconcile constantly with others. In their writing, in their personal lives, with themselves. Like Angie said, sometimes I do feel we are forgotten and feel pressured to perform my identity. I wonder how my writing will be received. Where is it going to go under? The concept of ethnic literature is always an interesting one to me. It feels limiting. You can be born here but it still feels like you have to “cross-over.” Cross-over from where? The in-between? The borderlands? I feel very much American because I was born here. At the same time, I am very much Latina. I speak Spanish, I am very attached to my culture. To hear someone even question my identity, that I’m not really an American, is still jarring.

SC: You need to remind these people that you were here before the world was round. That’s what I like to say about Latinos. We’re from the Americas. We have been here millennia before even Europe discovered us. You need to say that.

TS: Strangers have asked me, “Where are you really from?” I respond, “I’m from Los Angeles.” But then they still ask, “No, but where are you really from?” My first response isn’t good enough. It’s not good enough to say that you’re not from Pennsylvania, but from California. When they press the question further, I hear, ‘You don’t look like us, you have to be from somewhere else.”

AER: I’m a naturalized citizen. But I’ve been in the U.S. since I was three months old. So, am I American?

SC: [singing to the tune of ‘Natural Woman’] You make me feel like a naturalized American!

AER: I got a little flag and everything. It was great. I was twelve. I had to take a test to be here. I had to wait in lines, do paperwork, I had to be an “Alien” for a really long time. I had a card that said “Alien” on it. Resident Alien. But, I’ve been in the U.S. since I was three months old.

Clarissa A. León: How interesting would that be now— with DACA and all that’s happening.

AER: The thing is that my parents came here privileged. We came over with papers. My father purchased half of a U.S. business that employed five Americans which is an automatic reason to be granted a visa and then residency. It is not your typical immigration story. But, fun story— I was at PEN—at a PEN-America party. I was talking to some agent and she was asking “what’s your immigration story?” I told her roughly my immigration story, and she’s like “Oh, so you’re not an immigrant, immigrant?”

AV: Someone said something like that to me. I was telling them about Williamsburg, Virginia, which my parents are obsessed with because they like learning about American history (it’s new to them). Someone was like, “Oh, so your parents aren’t like typical immigrants that came to this country with nothing.” What is nothing? My mom was a secretary, and my dad didn’t speak English. It was such a weird question to be asked. It was somebody that volunteered for the Obama campaign, was a lawyer, lived in San Francisco.

AER: Ah. Well-intentioned white people.

AV: Yes, I didn’t know how to react. What do you even say to that?

ERF: It feels like we have this rich, amazing body of narratives in literature and in our personal lives. And yet, at times it feels as if people can only pick from five stereotypes and categorize everything into them.

AER: It’s hard to be a white savior if the people you want to save are ok. AC: There’s nothing to save!

ERF: It’s just hard.

AG: The question—“where are you really from?”—is common. It’s not necessarily unique to any one of us. It happens to all of us. At the same time, I think that if we start internalizing that question as both the beginning and the end of our narratives, then we start thinking about our narratives vis-a-vis that question. Doing so automatically discards the possibilities of what your narrative could be on your own terms and not on the terms of what and whom you’re addressing when you respond to this question. Rather than thinking of your work through, “why is my story always being questioned on whether or not it’s American?,” rather than privileging that question, could you privilege a different one, “What is my narrative?” Period.

ERF: Letting your narrative create new questions.

AG: Right. I don’t work in narrative or literature per se. I work in theatre and performance studies. I am in conversation with people whose narratives, which are sometimes written, are meant to be embodied and performed live. Those Latina/o playwrights aren’t published in the same way that fiction, poets, or nonfiction writers are published. Theatre’s primary mode of circulation is not the printed page. I am also in conversation with young undocumented artists, a lot of whom are writers. For them, the narrative of writing to America and of wanting to be American is problematic if this does not question what “America” and American citizenship mean. Who gets to embody these ideals? Taking the naturalization test, or answering the questions “are you really American?” and “what kind of immigrant are you?” These aren’t the beginning or the end. It’s not that they shouldn’t be engaged. It is that they cannot be the primary focus of our work or of our art. But I am not on or from the outside. I understand that I’m very privileged: I am a U.S. citizen, I was educated at three different Ivy League universities, and I am a professor who has held not one but two tenure track jobs. I understand the privileges that my birth certificate and education have earned me. Nevertheless, while listening to this conversation, I don’t know if we should be privileging the American question without questioning why we do so. One of the things that has been happening in Latina/o theatre across the country is this organization called The Latino Theatre Commons. When I attended one of their conventions in 2015, I kept hearing their motto that “Latino theatre is the new American theatre.” But this motto does not in and of itself imply, let alone include, a critical engagement with what it means to be American. Appealing to “America” to include Latinidad does not automatically gesture toward understanding America and its citizenship protocols more critically. This appeal achieves the opposite: it becomes part of an assimilation agenda. The motto is asking to have a piece of the cake too because we too are American in the same way that “you” are American. That you is whiteness because it signifies catering to a white imaginary of what American means… I think that a lot of what I am saying is coming out of my own angst about wanting to find these stories that do not privilege (white) cultural nationalist ideas of America as the beginning and the end of our work and of our forms of art.

SC: Are you a playwright?

AG: I am not a playwright. I used to not even identify as a writer. Helena Maria Viramontes knocked sense into me one day when I told her that I wasn’t a writer. She turned to me and asked: “What are you? What do you do? Don’t you write?” I said “yes, ma’am, yes.” When Helena speaks, I listen. That is when I started rethinking my relationship to writing. Am I a writer? Yes, in a sense. I write academic essays, I’ve written nonfiction work, poetry, translations, and conversations with artists. I am a writer, in a broad sense. At the same time, I am also a pseudo-visual artist. That puts me in this kind of conversation.

ERF: Even as academic writers, we share a lot of the same pains and processes as creative writers. Things like time, and finding space for writing.

AG: The first time I read Sandra Cisneros was in my Spanish class in college.

SC: Even though my work is in English, you read it in Spanish?

AG: The first time I read any writers of color was during my first year of college, when I took two literature courses. One was called Chicano Pop Culture and the other was called The Mexican Revolution Through Film and Literature. We read “Eyes of Zapata” in the Spanish class because it was about the Mexican Revolution. We read it right after we read Nellie Campobello’s Cartucho. I think you and Campobello were included in the part of the syllabus that talked about women and the Revolution. The professor included the “Eyes of Zapata” from Woman Hollering Creek in that section, and that was my introduction to Chicana literature.

SC: I thank your teacher because that was the most difficult story in that collection.

AC: After your work with Macondo and all these years that you’ve been an activist, what is something you would like to see as a writer, a woman of color?

SC: I gave Macondo fifteen years. Macondo is old enough to clean it’s own room. I started that and I still believe in Macondo and I hope they will find their home and go somewhere. But for me, right now, I feel like I am in a different phase in my life, where I have to focus in the short amount of time that I have left on the planet to grow. I want to grow. I feel like I was just born when I moved to Mexico. I’m in this new phase where I am going to grow spiritually. I think writing is a spiritual act. I don’t mean it in a religious sense, I mean it’s a spiritual act in that we do work of transformation. We do work of great transformation that heals people and heals our own wounds. That’s what I see. The times couldn’t be worse. If I’m going to work transformation in such a dark hour, I need to recharge, focus and grow and learn to be wiser than I’ve ever been in my life. That’s what I’m focused on. What’s being asked of me keeps getting bigger and bigger. I just don’t feel like I have the answers. I don’t feel like I have the wisdom or the talent or the vision. I want to be that. I’m working on that: growing spiritually. I have next to my bedside people that I admire— James Baldwin and Gandhi, writers like that. I’m reading on a spiritual level because I’m on a spiritual journey. It’s my time to read books that are going to transform me so I can do the best work because estamos tan fregados. We are in the worst time ever. I still want to do the work that’s organizing but I need to focus on my own writing right now.

![]()

AC: Now that you have passed on the baton with Macondo. What is happening?

SC: Macondo still exists but now it’s in transition and leaving Guadalupe. They’re looking for a new home. I don’t know if it’ll be within an institution. I like the idea of a writers’ workshop for activism. Any color. Any activism. But people who are really serving some community. I also think it’s time for them to move. I don’t know if they are staying in San Antonio. I would like them to go to another place.

AC: In the southwest?

SC: Not necessarily

AC: What about Pittsburgh?

SC: If Pittsburgh would give them a home, wherever they could get to.

AER: My house!

SC: Macondo is looking for a home. I had to step back so they would step up. I’m watching them but I can’t hold them up anymore. Otherwise they won’t step up.

ERF: As someone who studies the civil rights movement, I really appreciate the focus on activism. Many of the activists I research never had time to really process and write down or publish their ideas and thoughts because things moved so quickly. So much of the burden of representing the civil rights movement as it was happening falls on the writing of Alice Walker and Toni Cade Bambara. It’s a beautiful idea to have a space for activists to take the time to write down what their process has been for them.

CL: Everything that’s been said has been very insightful. It makes me think about the stories being covered in the news media and also who’s actually getting attention as far as book reviews. I do believe looking at the VIDA count that the Latinx community is getting blindsided from major book reviewers, like The New York Times.

SC: The New York Times pisses me off. Before we were at least in the back of the bus, but now we’re not even on the bus .

AC: I was reading how even though Latino/as make up 25% of movie ticket buyers, we make up about 6% of all speaking roles in film – even if we are 18% of the U.S. population.

AER: It’s also us. We are not a galvanized community. We don’t work together. There’s no Latinx Twitter the way there’s Black Twitter

AV: There’s a little one.

AER: It doesn’t have the same cultural impact. You look at the media that is rising right now, you’ve got Very Smart Brothas, Black Nerd Problems, Awkward Black Girl. You’ve got a whole black critical arts community.

AV: There’s Remezcla and Mitu.

CL: But it’s also about a representation of the writers themselves. I find it so saddening. The VIDA Count looks at the authors writing across all media in the major publications like The Atlantic, The New York Times, Harper’s, etc. I rarely find any Latinx writers there, in some cases there’s not a single Latinx writer at any of the publications.

ERF: It’s sad that our culture is determined by a small select group of people controlling the publishing industry.

AER: I’m going to be stubborn and say it’s us. I’m going to say it’s us. Angie Thomas’ book is at the top of the YA charts. It’s unapologetically black. And the black community has supported it, has bought it, has moved around it. You look at Tyler Perry movies or the rise of Spike Lee. People that are supported by their community, and that translated to ticket sales. We don’t support our people the same way because we don’t have a solid agenda or cultural identity.

AC: But the Latino/a identity is very complicated with disparate histories and interests.

ERF: And they also support media from Latin America as well. That’s the main media house. Like Univisión.

AER: Univisión is the closest thing we have to our unifying force. Jorge Ramos will save us.

CL: I think it’s a cyclical thing, representation. You don’t see yourself, you’re not going to go because you don’t see yourself, and it’s because nobody is there to make sure there’s something for you. I cannot think of a single major motion picture that has a protagonist who is Latinx where she isn’t misrepresented in some shape or form.

AC: Or she’s not playing Italian, or Greek, or ambiguously ethnic.

AER: Fools Rush In, maybe. Salma Hayek

AC: That’s so old!

SC: Did you see that movie Beatriz at Dinner?

AER: It made me uncomfortable in all the right ways.

CL: Hamilton! That’s about a white man in American history.

SC: That had to be about a white man or else otherwise white audience wouldn’t go see it.

AER: Also, some Latinos identify as white. There is no pan-Latino identity in the same way. We don’t have the same cultural backdrop like Black Americans do. A common shared history. Even people at this table. We’re all different kinds of mutts.

SC: I like that this conversation began with us drawing the United States.

To read the entire conversation check out our new issue, FALL 2017: Dirty Laundry Issue.