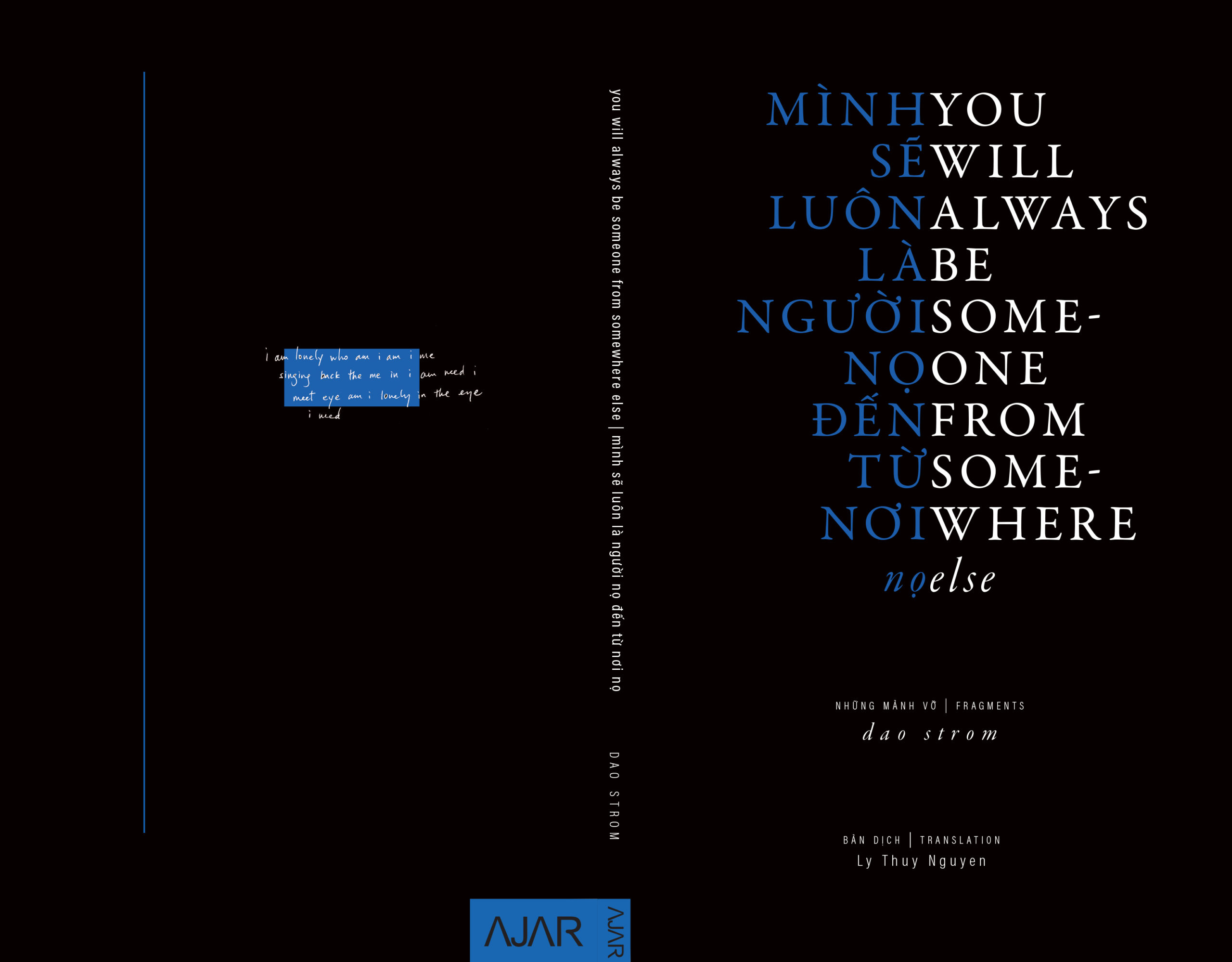

Where do I begin to introduce you to Dao Strom? Do I begin with her seduction with sound? The sultry provocation with her own vocal cord or instrumental cord, let’s say guitar? Or her irresistible, indestructible arrangement of images? Is Dao Strom an architect of image, word, sound? She is a poet, but you will find quickly that the Buddhism or monotheism or spinal cord of that word is limiting. As you enter the pages of her intoxicating bilingual poetry collection from Ajar: You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else, you will discover, as I have discovered, that the slow, seductive music of her polychromatic creativity and her diverse artistic longing are arranged with the seas in mind: sea of unity, sea of separation, sea of disruption, sea of departure, sea of “not here, not here,” sea of space and more space, sea of white pages, and sea of cannot, sea of silence, sea of insulation, sea of insinuation, sea of nonfiction, sea of history, sea of loneliness and sea of solitude.

You will notice the dexterity of her art, how she is willing to use everything (poetry, art, memories, travelogue, photography, image art, piano, bells, harmonies, acoustic and electric cities of words to create a language that is geographically symmetrical to her heart and tongue and where the mind can memorize, but cannot pinpoint or pigeonhole. Her beautiful work from Ajar moves like a decapod: organic and it flows. Or, after you depart from the cinema of her sea, you may ask, what or who is she? And, why is she able to dismantle my soul so easily? With a few gestures of her aching voice, aching image, aching language? Aching structure of irrepressible beauty? And, the breathtaking landscape of distilled despair. And, how is she able to make desolation so compellingly hospitable? What is her secret?

When you encounter her work on a macro scale, outside of her poetry collection from Ajar, a bilingual press based in Ha Noi, and spearheaded by two brave women, into the impartial void of her entire work as deeply presented to you on her website, you feel that sound and image are individualistic in themselves, distinguished from one another, like a clover from a spade, but they are also unreasonably interchangeable. For certain, her beautiful work across all genres creates a nomadic, pluralistic residence in my heart where I ache each time I read her work and listen to her sing her songs. She is a filmmaker, poet, photographer, songwriter, performance artist, Vietnamese American, and so much more. The substance of who she is in this chaotic world exists in her unlimited ability to measure timelessness with her art. I ache each time I visit an image she has so diligently and tenderly placed on the alcove of her existence. I ache each time I visit her website.

I write this because the interview between me and Dao is more or less rational-based. Which is to say that you will get to see an extension of her insatiable mind. As you explore the thoughtful, deftly responses from her, you will realize that she is no onion, where if you peel one layer, another layer of her will be revealed, and then you will discover by the end of your onion journey, there is no more layer of her to peel. She is, to me, an eggplant – nightshade, peel-able without an end, and purple and oval like the vastness of our universe. Our interview may be designed to introduce and welcome you to her You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else. However, I feel it’s closer to a cough or a sneeze or one hiccup that may or may not go away. Regardless, I am privileged to have this great opportunity to invite you into her captivating world, where you are lured into being worshipped and worshipper.

You can find the vastness of her creative brilliance and allureness here: https://www.daostrom.com/

Be sure to begin with her East/West. Like this interview between Dao and me; she writes, “These songs cross countries and cultures.” Dao’s voice is sad, like her poetry, filled with nostalgic debris and human rind and it liberates the space of your consciousness and heart in ways you can define your artistic self and purpose by existing more with her.

![]()

VI KHI NAO: You are in Paris, yes?

DAO STROM: Hi Vi, yes but actually I am in Corsica at the moment, retreating in a house by the sea with 8 women writers of the Vietnamese diaspora – we are part of a collective project called She Who Has No Master(s). This collective formed to explore dialoguing, collaborating, and sharing, as Vietnamese diasporic writers, across borders. In our gathering here in Corsica, we have mostly Viet-American writers, but also one poet from Canada, and one French-Vietnamese author.

VKN: You are somewhere beautiful says Ana Božičević. She says Corsica is in Greece?

DS: I’m told it is technically a part of France, but used to be part of Italy (was colonized by France). For periods of time, the Corsicans were very resistant, forming independence movements, I hear… It is an island, on the Mediterranean, and maybe suitable as a place between places, for this gathering…

VKN: I am trying to imagine you, where you are geographically. I realized that geography isn’t my strong point. I will pretend that you are married to a space that looks like sylph or a hummingbird. Thank you for enlightening me, Dao!

DS: It is in the south of France… I like the idea of thinking of it as a space (and I just looked up the word sylph). Yes – the light has a special quality here. Isa (one of our group) said the boulders by the ocean have “no nation.” So maybe we are searching for geographies, for landscapes, where we can — at least for moments — blur our sense of borders and definitions. (Self-definitions, especially, too perhaps)…

VKN: Yes, self-definitions. I like that. I slept poorly for the first time in months and my mind isn’t as sharp or pliable or as whetted like a bamboo…

DS: That is ok…! Ask anything you feel like, I will adapt.

VKN: You sew the narrative of your poetry with the panels and sometimes hemlines of photography. Could you tell us where your passion for photography and poetry begin? Did they happen at the same time?

DS: It has been a long road, let’s see… I have always been a writer, since I was a child, stories and (written) language were places of refuge and expression for me. But then I went to college and studied filmmaking (in SF) and that is where I first began to play with the visual mediums. Filmmaking taught me how to be very technical, I suppose, about the creative process of creating worlds, characters, stories; I had to think very pragmatically about creating shots and how to manipulate objects in an image. I eventually went to an MFA writing program and gave up on filmmaking, but the visual sense stayed with me. And eventually returned and began to influence the way I thought about words and images on the page, too.

VKN: How long did it take you to compose You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else? The book feels infinite to me, but also, like a silent, elliptical cinema with alternating frames of light and darkness as if you are teaching us about movement of identity and movement of history slowly one page at a time.

DS: That is a nice way of describing it, thank you. These pieces were composed in the wake of my previous book, We Were Meant To Be a Gentle People, which is also a hybrid of image-text (and music), a project that took me a good 7 years to find my way through… In the making of that project, I *found* my form, in the sense that I found the mode(s) I needed to express the different “voices” — or mediums — I felt inclined toward using. You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else was composed (rather quickly, in the months of March/April) using outtakes and out-growths (…) from that previous project. The images with wings are from travels in Vietnam and some from the Pacific coast, too.

VKN: The latter of my life I grew up surrounded by white people and for a long time and this may sound crazy or even absurd, but I didn’t think Vietnamese people made art, create visual or intellectual or emotional things, or write poetry in the United States. They did make art, but it was elsewhere. When I heard writers such as “Stacey Tran” or “Monique Tran” or “Le Thi Diem Thuy” or “Ocean Vuong” — I thought they were concepts created by white people to invite me to connect to another anthropological, fictional, or Martian fragment of the US. I get the sense that you were able to create more natural, creative connections with other Vietnamese? I am just beginning to understand this new language. What it is like to be well-versed in this?

DS: It’s so interesting that you see me as well-versed or connected to other Vietnamese… In all honesty, I have long felt very disconnected. I also grew up surrounded by white people (small rural town, very conservative, white stepfather), and I don’t speak or understand the Vietnamese language. A lot of my work as an artist has stemmed out of this sense of disconnect, perhaps too out of the sorrow/lament of it, of feeling like I don’t — and cannot — ever fully belong to where I am, nor where I came from. My sense of displacement in the world has always been quite strong. I can connect this to some fundamental aspect of being, but I also see that it has quite logical ties to history — to Vietnam, the exodus, the trauma of war and its invisible echoes… It may’ve been in 2003, when my first book came out (the same year Monique Truong and le thi diem thuy also published their first novels), that I really first began to meet other Vietnamese American writers. I was invited by Isabelle Thuy Pelaud, co-founder (with Viet Thanh Nguyen) of Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network, dvan.org, to a reading event in San Francisco that featured Vietnamese diasporic artists, including writers like Monique and Thuy, too. Over the years since, I’ve developed a relationship with DVAN, and their related blog, diacritics.org. Along with Isabelle and other women writers, in 2015 we initiated the She Who Has No Master(s) collective, as a space in which to share our experiences and collaborate creatively. Visibility and community, however, have been slow aspects to form — and I would say much of this is due to racial expectations and biases in U.S. society; there is still a lot of work to be done, that could be done, to fully hear and see all the nuances of the Vietnamese diasporic experience (which has so very many variances in it, no one story is representative).

VKN: What are some of the racial expectation and biases you experience or notice? Do you feel that your book addresses this?

DS: I think the general American perspective on Vietnam is a convoluted mess of a story, that I can’t succinctly sum up. But I might say, in the four decades of my own (American) life, I have grown up in an America that perceives Vietnam predominantly, and first, as a war, or a wound, or a spectacle of media and polarizing rhetoric — as a political conundrum — before it ever perceived Vietnam as a culture and a population of equally human people. The narrative has been dominated by white men, military narrative perspectives, and also by the wounds of how America suffered from the war. In my own experience many Americans did not (do not) exactly understand the history of North and South Vietnam — in short, the nuances of the history and the culture.

VKN: When I was in Florida, a man with grey beard who looked like a short Sean Connery, approached me and said, “I am sorry for what we did to your country.” I was stirred by his apologetic gesture and felt deep tenderness for him (as I could not understand why a man could apologize for an entire nation, but I guess one could) and did not feel the depth of genuity and sincerity of his country’s words until I met him. Have you had an encounter like this?

DS: I have had encounters like this, yes. Often white veterans wanting to share something of their experience in Vietnam, what they suffered from having to fight in a war they may not have fully believed in, that they feel shame for and much conflict. At one music show I played once in Oklahoma, a man came up to me afterward and told me he had been a Marine in the war, and that he felt my music could provide “healing” for many men like himself. I find these moments and encounters tender, and — case by case — some more genuinely felt than others. In the moment, I am always willing to be present for another person’s experience. However, in these exchanges I’m also aware of an underlying current that can trouble me. Because we, as Vietnamese-descended people, also have our own stories to tell and feel our way through…we are not just here to be a catalyst of either healing or reminder of past horrors to these men who experienced an awful war in a place that, though I have no memory of it myself consciously, lives in me in a much different way than it does in those men. In short, I think it is important to recognize that the Vietnamese people and stories exist — and should be given space to be seen/read – independent of the experiences and perspectives of Americans, especially white men. The Vietnamese diaspora (descended out of circumstances of war, but also so much more, including whole lives spent growing up in America) have their own experiences and art to express. They are not just reflections or obstacles against which the white (male) American perspective of the war plays itself out.

VKN: I am moved and I am happy that you are voicing this. I have felt versions of this pigeonholdedness when I am told to write more “ethnically.” Do you feel this pressure when you are creating your own work? My experimental writing feels very Vietnamese to me and yet, because I don’t include or write in the “ethnic” markers of my reality, readers have not validated my “fluency” in English and my “fluency” in Vietnamese. It is for this reason that I love reading your book as I felt connected to Vietnam from a remote, intimate place that could not date itself back completely or turned its imbued, all encompassing gaze back to guilt-infested “American culture.” I like how the lens of perception is pointed towards art, as it is a language that could annihilate all borders and it is in itself transformative. Your book, in both visual and linguistic form, exhibits this imagination without parameters very well. What kind of conversations did you desire from your work?

DS: These are interesting perceptions, too, especially about your own writing. I see the experimental forms as a just as potent (maybe more so) way of addressing, and resisting, some of these racial-stereotypes and pressures/expectations. My experience of your writing has been a sense that you are working on subtle currents, and they are not (to me) definitely western or typically “ethnic” (which is the way western readers might feel more comfortable with experiencing your “Vietnamese-ness”) — instead, there is a sense of another way of experiencing time and narrative and interiority…(I am trying to find the right terms as I try to articulate this…)

DS: One of the problems about the American publishing industry’s perception (and expectation) of “ethnic” writers, is simply one of a western-centered mindset: they define the “ethnic” experience as being an immigrant one — how that particular group entered America, becomes assimilated, etc etc. For myself, I was seeking, and still am, how to define — and how to really feel — what it means to be of Vietnamese descent in a way that, perhaps, reaches beyond war — beyond our relationship to imposing forces i.e. America and external nations. When I would ask even Vietnamese people what it meant to be Vietnamese, I would be told again and again stories about war — thousands of years of war, against the Americans, French, Chinese, etc. The quiet question inside myself kept wondering who we were before war, and if/how that was possible to perhaps meet, or uncover?… Maybe hints of reaching back to matrilineal society or indigenous perspectives are further questions along this thread. Because I feel that the imposition of the war-dominated “self-definition” (to go back to that earlier term) is largely due also to the advent of a patriarchal paradigm.

VKN: I always felt that US involvement in Vietnam was born from the delirium or an infestation of continuing the machination or war or the language for war because it’s only narrative the world seems to speak, but doesn’t understand. I feel any war, current or past, is a victim of limitation. That it’s hard to imagine a world without wars and to imagine a peaceful existence is to imagine death or misguided impracticality or uncertainty. War is certain and peace feels uncertain? This is why despite our familiarity with the language of war embodied in our being as human time and space, it always feel so foreign or alien to us. This is why I was so drawn to experimentalism and I assume this is the reason why you are drawn to it too because we want to create a political, artist, literary dimension that won’t promote predictable narratives that reinforce past certainties: cruelty, genocide, rape, and indifference.

DS: Yes – absolutely. (I wish you could be here to converse with the other women writers on this retreat…!) I would agree with that line of thought — war as a *certainty* that thwarts the fear or discomfort of realizing — of accepting — ambiguity, and how these elements are the basis of much violence — which essentially begins with the conceiving of one body as separate (other) than your own. I think that we are living — in this time and in the west — within a consciousness that defines itself via founding acts of division and separation; and yes, peace — union, stasis — is fairly inconceivable within this concept of humanity. But I see experimental forms, that take into deep consideration the shapes and contexts and narrative constructs of things (and these as important choices to make), as one way of refusing to perpetuate those prevailing ideas. It seems that you have made use of experiments in writing for the same underlying reasons.

VKN: I wish I were there too. Why did you give up on filmmaking? What medium do you feel most at home in?

DS: I feel like writing is very much like breathing and thinking for me, so I might say I am a writer first, but also that I’m not interested in being only a writer anymore. Music is the medium I perhaps enjoy the most, though, because I can lose myself in it – into a state of ethos, feeling, simple expression. As I see it, working in hybrid forms — pursuing *literature* through various modes of expression — is my own attempt to develop myself more wholly, as a person, as a perceiver. If I am to talk about separation (which includes the divisions and disconnects within myself) as a problematic, then maybe I should also use my process to try to rectify that within myself. But also — more simply — I love the way that sound/music engages language differently, perhaps more emotionally, than just seeing it on a page. Same with visuals. I think literature, which is essentially the art of storytelling and of sharing experience, can and should engage all the senses, potentially: language, sound, body, etc. As for filmmaking, for me it was a young pursuit and perhaps I wasn’t cut out for that ‘industry’ ultimately; but I still find myself working with video and experimenting with documentary techniques.

VKN: What is your preferred place to visit when you were in Vietnam or in the world? How has travel help you with writing?

DS: The most resonant places in Vietnam for me to visit were the Champa ruins — namely, the Banh It towers near Quy Nhon — and the caves in the Phong Nha National Park area. I am drawn to natural landscapes, and to the textures and elements of the physical world, rocks and water especially.

VKN: I love Quy Nhon, or the travel from Saigon to Quy Nhon. One could view the height of the sea running beneath the road from the bus. Speaking of resonant places, will you tell me more about Ajar? Its editors/translators. How was the connection established? If I remember accurately, Ajar is born and established in Vietnam, yes? Being published there should widen the demographics of your readers, yes? What is your vision for its publication? Readership-wise? Did you want to have a more direct conversation with Vietnam?

DS: Ajar Press is the brainchild of a Vietnamese poet, Nha Thuyen, and an American poet-translator, Kaitlin Rees. They are based in Hanoi. They publish an online journal, as well as a print one, and they publish a series of bilingual poetry books as well, called Fish Eyes. I connected to them when they reached out to DiaCritics (the Vietnamese diasporic arts and culture blog I mention above) and dialogues ensued from there. I was struck by their feminist and experimental — also, their unabashedly playful — aesthetic bent. Kaitlin Rees just received a PEN Translation grant for a book of poetry she is translating of Nha Thuyen’s poems, in fact. I think they are doing a wonderful, daring job of inhabiting and exploring the interstices, so to speak, between languages, time periods, and Vietnam and its diasporas in the west…As for publication hopes and readership, I have to admit I am not strategic, and I try simply to trust. Ultimately, I am always searching for connection, and trying to do the most honest work I can make; and then trust/hope for it to find its readers or listeners or viewers. It is meaningful to me that Ajar Press is based in Hanoi, and that my writing will get to appear as a bilingual book. And I hope it will offer something to the readers that happen to find it.

![]()

VKN: Our conversation is passing through different geographical boundaries. When we started conversing, you were in Corsica and I was in Brooklyn, conducting our conversation in Ana Božičević’s apartment. And, now we are in the same coast; you are back in Portland and I am in Vegas. How does it feel? This transition? How was your retreat? Was it fruitful? Did you accomplish what you wish? Would you generate a similar retreat in the United States? Possibly in the West Coast? What will you do in Portland now that you have returned?

DS: Hi again, Vi, and yes our conversation has carried across geographies…

DS: When I last wrote to you I was listening to the birds outside my window in Corsica, and was being greeted each morning by the sunlight and the sea there…I was sharing meals and stories with 8 other women writers, and we were working on our collaborative reading (a prose-poem with 9 voices, translated into French and Vietnamese, so a trilingual effort…) which we performed at the American Library in Paris on May 27th. So it’s been a whirlwind of places and people, voices and sites, and then I was back in Portland, just in time to co-host a Portland-based collaborative event (de-canon.com), and then see my son graduate from high school. So, it has been a full and eventful spring so far.

Being back…first, I’ll say that the retreat in Corsica was quite healing, and bonding, to spend that much close time with other women writers, to devote our energy to topics and themes related to being of Vietnam, and to have the gift of being in a beautiful location to do so — was all very special. Meanwhile, the politics of America continue, and I returned to a very tense Portland, just following the racist attack on the train (you may’ve heard, where two men were killed), which felt, to say the least, quite discomfiting. It’s hard to fully enjoy retreat and respite periods, knowing that the divides and violences continue here, and that the racial situations of America (and the world) are impossible to escape, really. I try to sight the small work that I can do in this particular community — which for me amounts to advocating for spaces for voices of color to be heard and represented well. Poetry seems a tenuous resistance effort, but since art is important to me, I try to believe it can be so for others too.

As for what is next: I will work on editing the Somewhere Else manuscript for Ajar Press, and keep working on other projects as well. I want to mention the She Who Has No Master(s) collective again and our plan, for next year, to enact our project in Vietnam. So our next retreat and reading event will — hopefully — take place in Vietnam. We are beginning to talk to Ajar Press (and others) about potential interactions/collaborations. (And would love to have you join us too next time, if possible!) So, my main hope is just to keep having dialogues, and crossing borders, and using art (writing, music, seeing, etc) as a vessel to enact and feel and also record these journeys.

Dao Strom is the author/musician of two books of fiction and the hybrid-forms memoir We Were Meant To Be a Gentle People + music album East/West. Her bilingual poetry book, You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else, will be published by the Hanoi-based Ajar Press in 2018. Her work has received support from RACC, National Endowment for the Arts, Precipice Fund, and the Creative Capital Foundation. She is the editor of diaCRITICS and co-founder of two collective art projects, She Who Has No Master(s) and De-Canon. www.daostrom.com

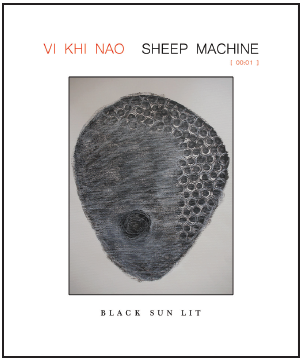

Vi Khi Nao’s SHEEP MACHINE is a textual inscape, a poetically painted nonfictional pasture where mechanical violence and visceral fear coalesce into a kind of science prosody, a post-human panorama whose beauty lies in the ruins of reality it depicts. Influenced by Leslie Thornton’s film of sheep feeding in a field as a conveyor belt of cable cars ascend and return from a mountain in the Swiss Alps, Vi Khi Nao takes perception into tumultuous terrains, into a pastoral-celestial void in which temporality is transcended, progress is a bourgeois invention, and god is a liability for our life spent in hunger and grazing. Vi Khi Nao’s SHEEP MACHINE is grace said at the ontological last supper.

Image Credits: Dao Strom

VI KHI NAO is the author of seven poetry collections & of the short stories collection, A Brief Alphabet of Torture (winner of the 2016 FC2's Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize), the novel, Swimming with Dead Stars. Her poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her book, Suicide: the Autoimmune Disorder of the Psyche will be out of 11:11 in Spring 2023. A recipient of the 2022 Jim Duggins, PhD Outstanding Mid-Career Novelist Prize, her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. She was the Fall 2019 fellow at the Black Mountain Institute: https://www.vikhinao.com