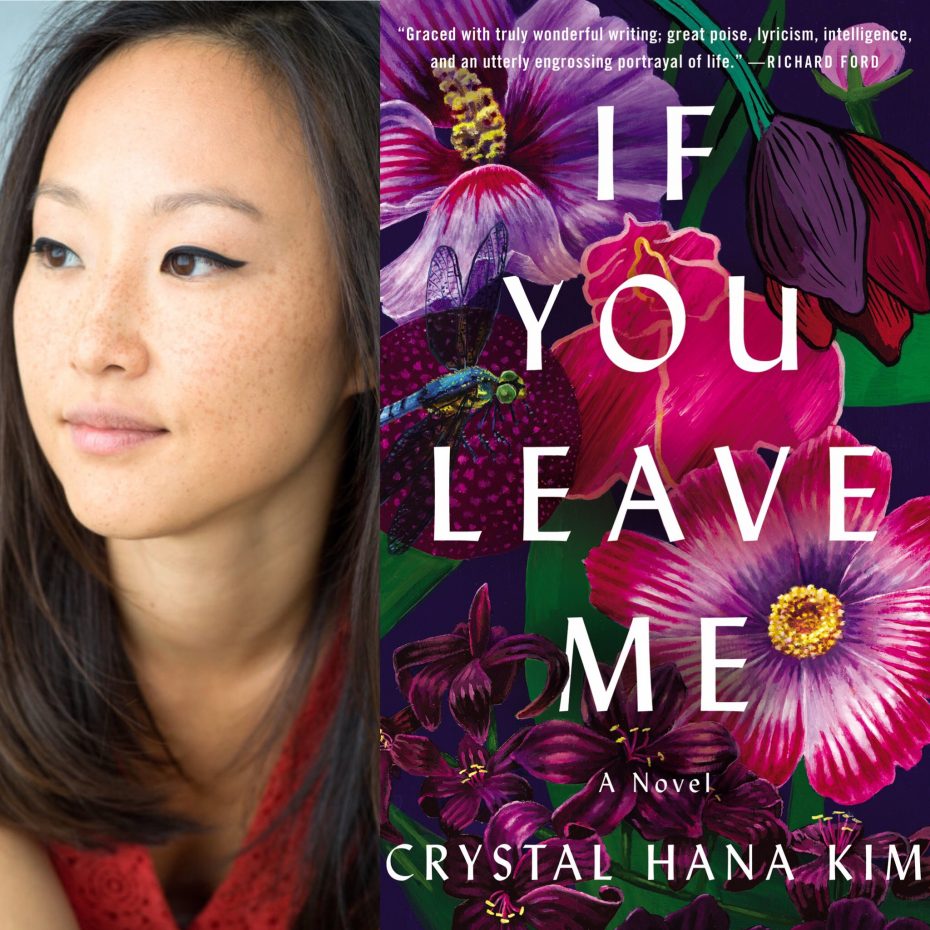

If You Leave Me, the debut novel of Crystal Hana Kim, consistently topped best of lists for 2018. Though the hard realities and complexities of the Korean War are evident on every page, one cannot discuss this great novel without running into romance. And so our interview covered all manners of love: the economic realities of marriage, shifting courtship rituals, familial heartbreak, how to fall in love with antagonists.

The interview was held at the Pittsburgh August Wilson Center’s Familiar Boundaries/Infinite Possibilities, a multimedia show featuring twelve artists exploring the expansive and constricting intersections of Black art and identity.

HE: The thing that struck me most about your book was the vividness of the environment, the intricacy. I think we should start here, did you visit Korea to write this novel?

CHK: My father is one of nine children and most of his side of the family live in the New York area, so I grew up deeply immersed in Korean and Korean-American culture. But my mother’s whole family lives in Korea. She’s the only one here. So we also went back every summer to visit them when I was little. Once I decided that I was going to be writing about the Korean War, I quickly chose to begin with a young teenage girl who was a refugee. My grandparents had to flee their homes, and I wanted to understand how that experience could change one’s life irrevocably. I developed and imagined the novel from there, but what I realized early on was that I wasn’t getting vivid details down on the page.

By having others read my work in workshop, I realized you can accumulate all the facts that you want when you’re researching but it’s not going to make the lived experience feel true to the reader. I had to go back to the characters’ lives. I shifted my research and started asking more questions, not just about dates or the countries involved, but about the daily lives of refugees. I asked my grandmother, what did you eat during this particular time? What did your home look like? What did your pillows look like? Specific, granular details. I also looked at a lot of photographs and pored over images so I could get that vividness on the page. It was learning process. I think all books are, and especially with the first book. I was trying to teach myself how to write a compelling story that will feel true to the reader.

HE: Awesome. So, I’ll admit that I really love books that have romantic plots. It always makes me a little sad when people want to take these out of movies, like I get that it shouldn’t overpower a narrative or always be associated with women. Your story could have been told many different ways. Especially as a war story. What inspired you to have a romantic plot? And did you ever run into resistance, either from external or from yourself about going about the story that way?

CHK: When I started writing this novel, I knew I wanted it to be about the Korean War and I knew that I wanted a young, rural woman’s perspective. Because I felt like—I love war literature, but a lot of times it’s from the perspectives of the soldiers. I wanted to know, what are all the women doing? What happens to them when they have to stay behind? These questions about what a woman’s options would be during this time slowly started presenting itself to me through the character of Haemi. I spoke to my grandmother, who didn’t have a high school education and didn’t have access to money or any kind of stability, and her only choice was marriage.

I wanted to have Haemi confront these questions about having to make the ‘right’ choice for the security of her family. I knew that would revolve around who she marries, which then formed into a love triangle idea for the book. When I came to that point in my writing, I was hesitant. I was the source of my own resistance, because I was very wary of how that would be taken. I’m a young, Asian-American woman writer. This is my first book. I was worried about of not being taken seriously, or of my novel being brushed off as “just” a romance narrative. I spoke to a teacher of mine, who admittedly was coming from a place of privilege as a white man, but he told me that all the great stories of our time are about love. He said, Look at all this great literature, or at least what we have canonized as great literature. When it’s written by men and it’s about love, it’s taken seriously. So you should feel the power to do it as well. And if you write a good story, you can change the idea that novels with romance written by women are silly. I really took this conversation to heart. Love is a central part of the human condition. I realized that I needed to quiet that voice of resistance inside me. When you’re writing a manuscript, it’s not helpful at all to think about publication anyway, so I learned to block that off and follow the characters. I had to learn to be true to their lives and personalities and motivations, so if that means that Haemi has to choose between these two men, then that’s what she has to do.

HE: I don’t think we talk about that enough, the economic aspects of love, especially as immigrant daughters on the matrilineal side. And are there ways love is viewed differently in your life versus your family?

CHK: Yes, I come from a family that talks very openly. My grandmother would tell me these stories of how she never experienced true love. Her first husband passed away and then she had to remarry. There was always an economic factor to it, right? During that time in Korea, many women were not able to survive on their own. This reliance will necessarily color anyone’s experience of marriage. I think those complicated ideas were then passed down to her children. And then they were imprinted on me and my sister. The way trauma or tradition or just the ways we hurt is passed down through generations is really fascinating. When I’m writing fiction about family and relationships, it’s because of my own curiosity about my past. My history.

HE: So true. We’re forever bridging our past within our work, especially as it relates to love and romance. And I think that writers have to be romantics, especially when it comes to characters. A character like Jisoo, seems like a hard character to love however. How do you go about falling in love with these characters anyways?

CHK: I wanted all my characters to feel as real as possible. Which meant that sometimes, I was very frustrated by them. I needed to make sure that even through frustration, I loved and cared for all of them. One of the ways I did this was to understand each character individually before I started writing and then making sure to check in with myself throughout the writing process. From a craft perspective, I kept a document of character profiles. I wrote down all the basics—date of birth, physical characteristics, etc—but also really tried to understand their personality. If I knew this person in real life, what would we talk about? Where would we go together? What would we eat together? I did this for each character to create a sense of intimacy in the hopes that this would help me to care for them. I wanted to imbue them with compassion, even when in the novel, they are acting in ways I don’t agree with.

I was actually at a residency when I swapped drafts with a mentor, Sarah Ladipo Manyika, who is so wise and brilliant. She knew from reading the first 150 pages of my draft that I didn’t love one of the characters as much as the others. She said, if I can tell the author doesn’t love X, then I as a reader will not love or trust X. That was so helpful for me to hear. I went back and I checked in again with the character until I found that missing empathy. Only with empathy did I begin revising.

HE: And what was your process for developing more empathy for that character?

CHK: It’s similar to the ways in which I try to empathize with people in real life that I may initially struggle to connect with. I think to myself: What information do I not have? Who knows what their family life or home circumstance is like? Or their relationships with their parents or friends? Or what they might be going through professionally, emotionally, mentally? When I think of all that I do not know, it opens up new avenues of empathy.

I do this with my characters too. The benefit is that I can know my characters’ back stories. So I would think, if this person is acting this way, in this scene, I have to understand their motivations. The character might not understand their own motivations, depending on how self-aware I make them, but I must know. We’re all shaped by our pasts, our childhoods, our socioeconomic status, our gender, sexuality, relationships. The list goes on. So I really dug into my characters’ psychologies to understand their perspectives and actions.

HE: There’s almost this degree that being a good writer is being like a good-enough mother, how I imagine you sometimes have to let your child/character hurt, let them make their own choices. Even when you know it’s going to end in heartbreak. We in the West, romanticize falling in love as always ending in a positive. Did you detract yourself from popular romantic plots in regards to the love shared between Haemi, Kyunghwan, and even Jisoo?

CHK: Yes, yes. I think it’s interesting how in America, people romanticize and elevate personal relationships. We talk of marriage as an achievement, particularly for women. I remember in college speaking to a girlfriend who said she knew exactly what her wedding dress and engagement ring would look like. When she asked me what I wanted for my wedding, I had no idea. I wasn’t getting married any time soon, so why would I be thinking about those things? Similarly, I think American readers have a desire for clean, happy endings.

In writing, I was really driven by realism. In following these characters, I didn’t want to fall into the trap of a happy ending just for the sake of the reader. I wanted the lives of Haemi, Kyunghwan, Jisoo, Hyunki, and Solee to feel as true as possible to what I understood about the people growing up during and after the Korean War. I needed my novel to end in a way that would feel most realistic to the characters. Does that make sense?

HE: Yes, it does. Another realistic portrayal I really appreciated within this novel was Haemi’s maternal ambivalence, she didn’t hate her children, but there was a life of education she missed out on due to her motherhood and wifely duties. How did you get in touch with this aspect of your novel? What did you discover along the way rendering her feelings on motherhood?

CHK: I think we as a society don’t talk about the complexity of parenting, and of motherhood especially, enough. If anyone expresses any ambivalence, we are so quick to view them in a harsh light, even though it’s impossible for any mother to feel one hundred percent positive about mothering all the time. Again, I grew up in a family where people were very honest. As a young child who was good at listening to adults without them knowing I was listening, I would hear all types of conversations. When the women gathered, they often expressed frustrations about motherhood, of not being able to pursue whatever passions that they wanted. Those conversations always stayed with me. I realized they had found a safe space where they could talk amongst themselves without judgment.

And yet when I was out in the world, the mothers portrayed by society were always so binary. They were either perfect mothers who could do everything or they were simply considered ‘bad.’ I wanted to bring ambivalence into the narrative and show that it’s okay for a woman to have complicated feelings even after she’s borne children. Now that If You Leave Me is out in the world, I’ve had readers come up to me and thank me for portraying motherhood with honesty. I’ve also had readers who have said that they didn’t like Haemi because of the kind of mother she was. And I think that those differing assessments reflect how we are being raised to view mothers.

HE: Yeah, like I know in Nigerian culture, and maybe this is for Korean culture as well, motherhood is kind of the apex of becoming a woman. It can be scary to redefine womanhood away from actually mothering a child. Switching tracks, the question I have for you now is what surprised you the most in writing this novel?

CHK: Oh! What has surprised me? There have been so many little surprises along the way. Writing the first book is so special because you don’t know if anyone is going to read it, so what surprised me was how much I got from just writing. I really did block out anything that had to do with publication while writing this book. I found so much joy in writing and figuring out how to solve problems that came up in terms of the plot or character development. Now that I am working on a second book, its helpful to remind myself of that sort of, well not naiveite, but a sort of innocent joy. I am trying to hold onto that feeling.

Another thing that has surprised me is how my years of researching and then writing If You Leave Me has brought me closer to my family. But there’s a sense of loss for me as well because all of my adult family members—my parents and my aunts, my grandmother—can’t read the book. The English is too difficult for them.

And one of the greatest surprises has been talking to readers. It has been so lovely because I was nervous. It feels really vulnerable to have a book come out. I felt like a layer of my skin had been peeled off. But it’s been so pleasurable to meet readers, to talk to them, and to get messages about the ways this book has impacted them.

HE: So cool! We’ll wrap up here and I just want to say I so enjoyed your novel and learned so much about Korean culture. I weirdly loved Haemi’s disappointment—not like I liked her being disappointed per se—but I appreciated seeing the reverberations of that disappointment across the generations. That definitely made my heart break, but in a good way…I hadn’t seen that sort of female disappointment really written extensively on, so thank you for that.

CHK: Thank you for reading!

HE: Yeah, of course! Thank you for sitting down with me today.

Crystal Hana Kim’s debut novel If You Leave Me was named a best book of 2018 by The Washington Post, ALA Booklist, Literary Hub, Cosmopolitan, and others. It was also longlisted for the Center for Fiction Novel Prize. Kim was a 2017 PEN America Dau Short Story Prize winner and has received scholarships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Hedgebrook, and Jentel, among others. Her work has been published in Elle Magazine, The Paris Review,The Washington Post, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Columbia University and an MSEd from Hunter College. She is a Teach For America alum and has taught elementary school, high school, and collegiate writing. She is a contributing editor at Apogee Journal.

If You Leave Me is available for purchase here.

Hannah Eko is a writer, multi-media storyteller, and MFA candidate who currently resides in Pittsburgh, PA. You can find her work in B*tch and Bust magazines and on Buzzfeed. She enjoys geeking out on Wonder Woman, astrology, and the Divine Feminine. Hannah blogs at hanabonanza.com and enjoys Instagram (@hannahoeko) a little too much. You should ask her about love.