11am on a Wednesday

I started the day considering the figure but soon became preoccupied with the space. At the time the figure took up most of the space. The figure of my novel was Minerva. The novel was about 70% figure. The space, when completed, I hoped would be positive— filled with palms, flamingo flowers, the aqua of Colombia’s caribeño coast, inkblot skylines, life-alarming noise, the street urchins of London’s mid-70s. But at that moment, the figure was floating around in mostly negative space—90/10, I would say.

The figure picked at her skin, making little maps with the excess. I bit into my erasure and wondered if this was a way she created space. At this point in the novel, her space was cross-hatched with mothers, lovers, sour looks from strangers, and, on occasion, David Bowie. Life events punctuated the space, but couldn’t fully pin down the rotating settings. Minerva’s skin maps were the most stable landscapes, I realized. What happened to my understanding of the figure’s space when the figure reconfigured the way her body occupied it (or in this case, shed in it)? What kind of consideration should I give to the space created with skin? Should it be prioritized over snotty British mornings or pulsing Cartagena afternoons? I gnawed on the lemon peel in my tea, hoping to find an answer soon.

6pm on Halloween

As a gang of Harry Potter characters ambushed the candy bowl, I map solid spaces and implied ones in my head. Plaza Santo Domingo, Castillo San Felipe, Regent’s Park, King’s Road, Shepherd’s Bush, the runny yellows of Cartagena yet again—she moves through all, tying half-hearted knots between them as she goes. How does Minerva gestalt her way into a home? As if on a treadmill, the earth beneath her rolls away from her.

Sloped Earth: Leaving a land of freewill to return to the palm of your motherland’s iron st. Discovering that the st can crumble, like sand.

Sloped Earth: A disorientation. Leaving to come back. Coming back in order to get permission to leave.

How does Minerva’s relegation to negative space affect her behavior? If she understands her surroundings as cut-outs of home rather than brick and mortar, then perhaps this explains her tolerance of abuse.

Our experience of an architectural space is strongly in influenced by how we arrive in it.

London, 1975. The economy buckles. Anyone who speaks another language is politely asked to leave the post office. The Sex Pistols are turning their grimy heads inside Punk’s sticky womb. When Minerva arrives she notes a light drizzle watering the pink mohawks and shaved heads that dot Chalk Farm Road. She is wearing a cream dress.

8am on a Tuesday

I woke up considering the literary feng shui of my novel en-route. Am I willing to relinquish style for authentic voice? I revved up to rewrite a chapter in first person. It struck me as a human but not as the mother of the text. I’m not ready to hand over Minerva’s vocal chords to her yet. My punishment is that she hasn’t talked to me for days.

3am in a dark room

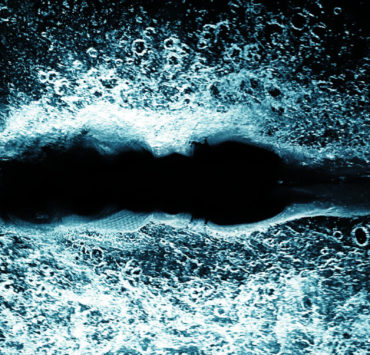

I fell asleep pressing my ear to a pile of poems. I plucked them from the spine of a book and laid them at the top of my bed like pillows. I wadded more and more sheets on top of each other, separating each poem with colored tissue paper so that they shone like embers in the dark. When I had built a nest for my head I lay it upon the poems. My ear crinkled the paper. I thought I heard the poems whisper to me. At night, I felt the surge of words absorbed into my body. I woke up with language.

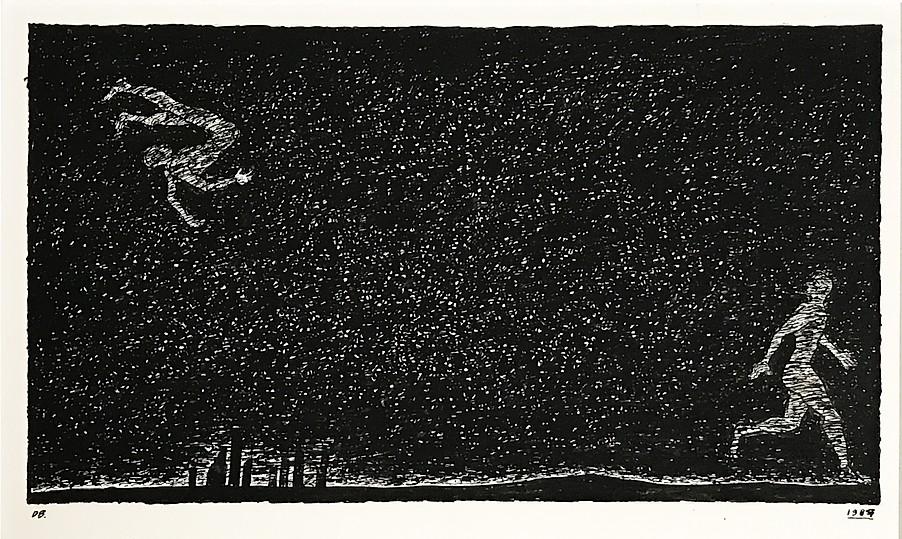

My day’s target was the poem. My route: the reading chair to the kitchen table to the bathroom, repeat. I had created my poem pillow to insert reward into my path. Sleep was a necessary path. I thought that lining sleep with tools that could encourage my target, yet disabling my ability to engage with them, might strike a rich balance of denial and reward. Enough to let language come to me like tightrope walkers—slow and precarious, but coming.

I wanted to protect them and to honor their journey, so I wrote very slowly. I cradled each one, flecking it out like the letters in a second- grader’s cursive journal. One by one, like beads of water rolling down a car window, they came. All but the last one. I wondered what I must deny to coax it out.

4pm in Los Angeles

I’m deciding if Minerva is the novel’s foundation, or just an attic window. Does she support or crown the novel? Will she continue to be a receptacle, or will she create her own container? Will she break out of the container that people place her in? Switching the label from spare linens to childhood toys? I know each room holds a journey—through continents, in and out of a ections and youth movements. Minerva is at the base of herself, the base of society, the base of culture burgeoning, but she can’t hold the book up by herself.

Minerva and her mother Valeria hold everything together. If Minerva is my base then Valeria is my roof. Valeria has the potential to either topple or adorn. She will do both. Her arc of descent is exquisite in its annihilation.

9pm on a Friday outside of Starbucks

I leave and promise myself I’ll come back because Valeria is not coming to me. When I strike her like a bell, only tin resounds. She takes no shape outside of her anger and addiction. Inflated by them, she’s too easy to puncture.

Outside I see a sports car with no permit parked in a handicapped spot—a visual representation of fragility. Whatever foundation they wake up in every day cannot be solid.

1pm on a Thursday

In the downtown o ce of the urban planning nonprofit I work at, we debate about the front door’s relationship to the wall.

10:30am on a Sunday when it is raining

I started the day hiking with a friend in Cherry Canyon. The dusty trails were wet and looked like sweaty camels. The landscape sighed as we progressed upon it. Our shoes became soggy from the mud path we mound up, thickening the further we walked. The flat smoke of the sky twisted and curled above us.

My painter friend felt she was groping in the dark. She had just completed a show that had given her nothing except a feeling of being intact, which was in fact everything. She asked me what we do as artists who can feel completed by acts that seem to do nothing—they have not resolved a social issue, they have not brought us money or fame—but they feel like a further wrinkle in the right brain, and this wrinkle has a healing property. The wrinkle tightens around our understanding of how we wish to move in this world. I tell her that I’m just going to keep following the folds. I’ll keep folding and folding until one day, maybe, I’ll have a fucking paper crane.

10am, November 11th, 2016

Two days ago, America elected a reality TV star and sex predator as its next president. How does he fit into my intercontinental family portrait? The distance of placing xenophobia in the 1970s, 5,000 miles away, feels like an indulgence. I am reminded of a quote: Cowardice is a form of decadence. My book feels like chocolate cake.

Has the U.S. performed a form of decadence? Our president elect is famous for yelling You’re red! at budding entrepreneurs. He’s also the face of WrestleMania. He now has control of my ovaries.

I received frantic emails from friends asking me about where to get an IUD. What if I want kids before the end of this presidency? Where can I take it out? I want to engulf them in my maze of positive and negative space. Build a home for them that way. Lock the new president out of the architecture of my fiction. Make this our new reality.

November 14, 2016

What is the architecture of this cowardice? Conservatives throw pebbles at the veil of diversity in the White House. The curtain sighs a little. But white Liberals laid the bricks. We wrongly believed “our” work was now done. Conservative America built upon this cowardice, using the belief, posited by the left, that our Black president would resolve our social disparities as cement. Conservatives were just fortifying the liberal staircase.

We built the foundation and they shellacked the walls with textured fears of the “Other.” Gradients of economic concerns, fear of losing social security, an allergy to Spanish, an a ection for the Confederate ag. Liberals constructed the house and Conservatives decorated. Like a fussy old couple we fought about the end product.

How have Valeria and Minerva performed cowardice? Valeria’s was enacted in abuse. Silence hardened her. She could not be persuaded of compassion’s cooling powers. Minerva allowed abuse to linger like her shadow until it caught her. Only then did she perform an exorcism. A space erects around her that she must then blow apart.

On a morning in which Winter warmed into Spring

I used to think inspiration would strike when I wandered into the unknown—a foreign city, a grand landscape, a strange romance. It’s easy to follow the impulse to write these encounters, but how do I write the familiar? Often times I shy away from it. It is too close to me. It gives the uncomfortable friction of a second skin—not quite on me but gently covering—somehow just out of reach.

November 2, 2017

I decided on eggs instead of cereal and mulled over the possibility of the colonial conscious scaffolding the novel. But I’m old-fashioned, and feel like I need a body to put to my narrator. How do I invite in a voice that already has its tongue on everything? It reminds me of the oil in Fern Gully. It comes hissing down, permeating everything.

November 3, 2017

I began the day thinking about what form this hissing consciousness would take. What formal constraints would it have? My professor suggested a hybrid screenplay/novel, but I’m not sure I want to give the oil another lens.

November 5, 2017

I began typing Juan’s voice, Minerva’s childhood best friend. Previously, he had been a pillar, but as I cast an eye across my landscape of characters, I wondered, is he not the pure embodiment of colonized thinking? A rich brat from the Walled City with socialist fancies who tries to peel o his opulent skin by joining los guerrilleros? Who wriggles back into the pelt of privilege when things get tough, and wouldn’t you know, it still fits him just fine. Who else to talk back at assumptions of class in European immigration patterns? Who knows the figure better than he?

2:30pm, Sunday, almost mid-November

I tentatively made additions. Adding a stone here, a high beam there. Then I got ambitious and began lobbing on extra rooms, a trembling third story. The extra rooms were filled with characters I cared about but that I was not sure were connected to the foundation of the novel. The novel started to tilt sideways and slide down the hillside. I weighed it down with a garage. I worry the house may split open from being dragged in two directions.

A Thursday evening, December

The success of the masterpieces seems to lie not so much in their freedom from faults—indeed we tolerate the grossest errors in them all—but in the immense persuasiveness of a mind which has completely mastered its perspective.

—Virginia Woolf, “ The Death of the Moth”

I have built a house that groans under its own weight. It’s a house filled with cracks that mice slip in and out of. Wind blows through it like a shape-shifting ghost. The house rattles with every haunting shriek. But at least I know where the silverware is kept.

Image Credits: Derek BoshierRosa Boshier is a multi-genre writer. Her work can be found in Entropy, e Acentos Review, e Rattling Wall, Necessary Fiction, Ghost Parachute, and New Delta Review, and is forthcoming in e Los Angeles Review of Books. Her plays have been staged at e Getty Center in LA and e Mission Cultural Center for Latino Art in San Francisco. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing at e California Institute of the Arts, where she teaches Latinx Studies. She has received support/artist residencies from the Rainin Foundation, Zellerbach Foundation, Bill Graham Foundation, Maker City LA, and Hannacc in Barcelona, Spain.