In the second year of the war, the President of the United States was accidentally shot while hunting at his ranch. The hapless hunter at fault was an invited guest, a sheepish Senator from Arizona, for whom the President had recently named a Western lake. There was quite a commotion when the President fell. The bullet lodged in his upper thigh and shattered his femur. There was much blood and unpleasantness. The hunting holiday ended abruptly, as the Head of State was taken by train to Washington. There, the President refused to see a doctor. The wound neither worsened nor improved, his right leg still attached by a filigree of tissue and muscle. The President’s made a few speeches from behind his desk in the Oval Office, but otherwise, stayed out of the public eye. People said he was depressed.

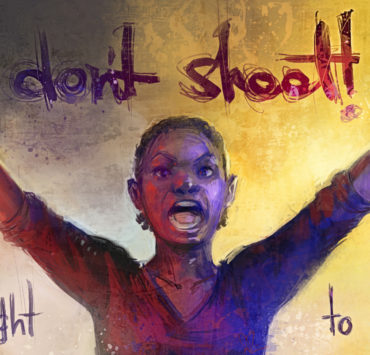

Figure 1: The President of the United States

Figure 1: The President of the United States

Meanwhile, the war was proceeding haltingly, almost comically: a bomb here, felling a bridge in Montana. A bomb there, in downtown Los Angeles, destroying an abandoned building where a few addicts sometimes slept. No one would miss these constructions, certainly not the President. “We have so many bridges! So many crumbling buildings!” he was overheard saying to an aide. The President took pills and herbs for the pain and, in his less lucid moments, he prayed. His wife consulted tarot cards.

In statements to the press, the President’s spokesman ridiculed the crazies and their crude bombs, their patchwork ideology and their irrelevance. His injury was not mentioned.

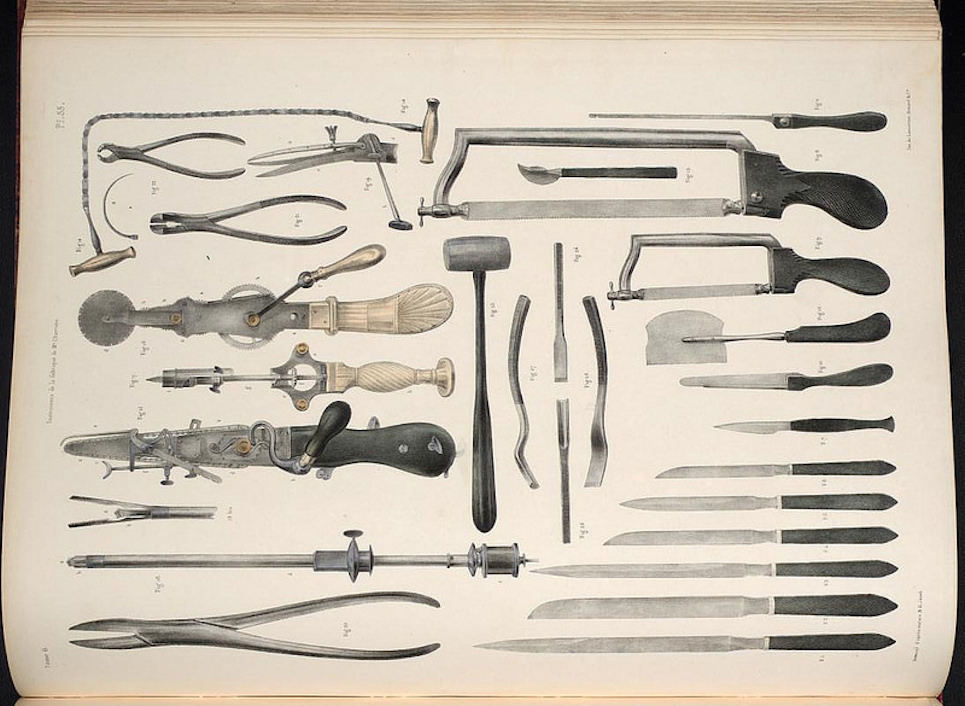

A specialist was sent for, a young European doctor. It was said that he was an expert. Around the same time, the subversives made public a communiqué in which they asked the nation to pray for the President’s speedy recovery. They lauded the decision to spend taxpayer dollars on a high-priced specialist. For the greater good of the Fatherland, read the document, every sacrifice is worthwhile. On his sickbed, the President was incensed. His wound was meant to be a state secret, at least until his campaign for re-election, but he had been betrayed. The rumors had swept through Washington and then throughout the country. He was being made fun of and everyone knew it. The specialist arrived from France and recommended the immediate amputation of the President’s left leg at the hip joint. The wound was yellow and gangrenous, the leg atrophic. “Have my reports been received?” the European asked.

They had not.

The specialist shook his head. “In any case,” he said, “there is no time for that now.”

How the amputated leg wound up in the possession of the subversives is not exactly clear. Perhaps someone had infiltrated the military hospital. Perhaps it wasn’t the President’s leg, but another unfortunate man’s leg. The masked subversives held an armed press conference in the remote Pacific Northwest beneath the high, green canopy of millenarian forests. The subversives presented the appendage. The gathered media was invited to touch it and photograph it from all angles. The subversives took off the leg’s shoes and socks, and played “This little piggy,” with the formerly Presidential toes. Godspeed, our one-legged Leader, they proclaimed. There were rumors. The amputation made the cover of the tabloids. The President ordered the offices of these papers shut down and fire-bombed. In response, the subversives organized massive protests, filling the streets of all the major cities. Thousands clamored in Times Square, along Lakeshore Drive. Traffic across the Bay Bridge ground to a halt. Cars were pelted with eggs. People carried placards bearing portraits of the hobbled leader: the President on crutches, the President pulling his stump behind him. At Camp David, his devoted wife brought him each morning’s newspapers. His convalescence was torture. Enraged, he ordered the French specialist detained, certain that the arrogant doctor had betrayed him.

His wife concurred. “I never liked his accent,” she said.

A week later, still tormented, the President ordered the doctor executed. The specialist, he concluded, was a sympathizer, an educated and frivolous European of the kind who were entertained by the spectacle of America’s decline. The doctor wept when he was informed of the President’s decision. His guards couldn’t wait to be done with him. In fact, he was so inconsolable that after a routine and uninspired beating (during which the specialist’s wailing grew almost unbearable) an impatient guard pulled out his weapon and shot the doctor dead, depriving the President the privilege of seeing the prisoner die. For this crime, the guard was also put to death.

Mr. President, as your medical handlers mentioned to me in their cable of last month, you are concerned about your wound. I assure you, I will come to your case without preconceived notions; my only intention is to see you once again well and at the helm of your nation’s forces. Of course you are fearful, and certainly you must be concerned. I will attempt, as best I am able, to put your mind at ease. Some background on therapeutic amputation is in order, and here, I can say that France has taken a pioneering role worthy of our national character. Indeed, the first instance of amputation for a gunshot wound of the upper part of the femur occurred in the French Army of the Rhine in 1793. The doctor in question was the illustrious Jacques Perault, then and thenceforth a zealous advocate of hip joint amputation. The patient, whose name is recorded only as S., bore the operation well, and for several hours afterwards his condition was most satisfactory. Unfortunately, it was necessary that S. should immediately follow the army in a precipitate march of more than twenty-four hours duration. It was winter. He died from exposure and fatigue. Undeterred, Perault again took to the knife in 1812, in this case to succor a subaltern of French dragoons named Goix, whose thigh was badly injured by a cannon ball at the Battle of Bordino. After surgery, the patient was removed to the Abbey of Kolloskoi, and thence to Witepsk, under the care of Surgeon Major Bachelet, until he was nearly well. Bachelet treated Goix with brandy and tincture of iron administered orally, while caring for the stump with daily injections of terebinth oil. Within three months, the patient had completely recovered. Perault celebrated, reportedly telling his aide-de-camp that a medical miracle had been achieved. In his memoirs, he cited this case as the first successful primary amputation, but as the patient never reached France, and his death is not accounted for, the adversaries of this operation will not admit it a success.

Years before he shot the President quite by accident, before the Second War of Rebellion, the Engineer, later Senator from Arizona, said: “A fine spot for a lake, isn’t it?” He was sunburned and loud, his booming voice echoing across the valley. It was the golden earth of the Reservation. His assistants smiled. Yes, yes, they said with their eyes. “A fine spot indeed,” repeated the Engineer. He drew a sketch on a napkin, and passed it to his assistants. “Well, get to it then,” he said, and lit a cigar as he strolled back to the Jeep.

The first year of the dam was known as the year of drownings. They came from all over: from Maine and California, from Florida and Illinois, to step into the turquoise water and breathe it in, to fill their lungs with it and die. Native Americans mostly, and their sympathizers, earthy people who had protested the dam’s construction at each step. They came and drowned in their indigenous costumes, plumed and painted as if for war. Their bloated and blue corpses floated to the surface. The Parks Service asked Congress for a pontoon boat to pull the bodies from the gentle waters. But there was no money. The war had begun in earnest. There were rumors that the President had been shot. It was the year of the Battle of Denver, the subversives’ first military victory of any import, and the government was struggling to make ends meet. So the bodies stayed, bobbing helplessly on the surface of the lake, and that summer a few intrepid tourists braved the war zone to visit the picturesque lake, to watch the sun set over the water dotted with dozens of floating, colorful corpses. Sea gulls, too, had somehow found their way there and flew over it in lazy, swooping circles. At dusk they could be seen pecking at the bodies, tearing at the waterlogged flesh with their thin beaks.

The Engineer, for whom the lake had been named, found no humor in its macabre attraction. He recalled that morning when he drew the first crude sketch of the place: the livid colors blooming from the rock, the bright sun, the altogether pleasing submissiveness of his assistants. It was a dream of his to see a lake there, and now the dam was in danger of becoming clogged with bodies. The whole Western power grid was in danger. He called the Speaker of the House. “I won’t stand for it,” he said.

He called the Senate Majority Leader and spoke with the same harsh tone of voice: gruff, pained, gravelly. He very nearly called the President, though they had not spoken since he’d shot him. In interviews with the press, he didn’t hesitate to call the body of water, “my lake.” After all, hadn’t he conceived of flooding the desert? And hadn’t the President named it after him?

Of course, there are dangers, Mr. President. It is true that the combined mortality rate for amputations by the British in the Crimean War and the French in the Franco-Prussian War was a startling 86%. These were indeed the dark early days of battlefield medicine. But you are right to judge that 10,000 dead out of 13,173 is not acceptable. And yes, you may have heard that amputations at the hip joint are particularly dangerous, with 100% mortality rate during those two military engagements. Yet I am optimistic for two reasons. First of all, the progress in these fields of medicine cannot be ignored. The survival rates have improved with each successive campaign so that by the time of the First War of Rebellion in your country, only 83.3% of hip joint amputees perished within a month! Secondly, I believe Americans are quite simply stronger and have within their grand and heroic souls a greater will to live. On this second point, I turn to Mrs. Phoebe Y. Pember, who wrote of her experiences as a matron at the Chimborazoo Hospital in Richmond, Virginia during the First War of Rebellion:

Poor food and great exposure had thinned the blood and broken down the systems so entirely that amputations performed in the hospital almost invariably resulted in death after the second year of the war. The only cases under my observation that survived were two Irishmen, and it was really so difficult to kill an Irishman that there was little cause for boasting on the part of the officiating surgeon.

I am told, Mr. President, that you are of Irish stock. Is this true? Take heart, Mr. President: the Irish are lions!

The President’s doctor’s name was Céphas. Before he was killed, he dreamed of Paris. He was in Washington of course, in the dim bowels of the White House, but he dreamed of the city where he was born: the graceful indolence of the Seine, the gentle winds, the bustling plazas and crowded, smoky cafes. His parents were Senegalese. His older brother sold phone cards at a subway stop in the 17th Arrondisement. His younger sister was a housekeeper for a wealthy couple in Montmartre. He’d never been to Senegal, had left the French capital on only a few occasions. He studied, excelled, and reached heights that he could scarcely explain to his mother and father. They wanted him to marry, to stop fooling with so much education. “A man in your position could have two wives or even three,” they told him. He laughed when they said things like this. “Ah, my simple parents,” he said in Wolof, and kissed his mother on the forehead. He was young, not yet forty, when he was called to serve the American President. Céphas studied the President’s condition in preparation for his trip. His family saw him off at the port. Crowded in a waiting room, his brother embraced him, pressed a stack of phone cards into his pocket, and said to call, “every day if you can.” The voyage by sea would take only two weeks, so improved were the newer fleets. There were tears in his mother’s eyes. Inshallah, his father said somberly, God willing, we’ll see you again soon.

Now Céphas dreamed of a Paris empty of people. Even in his ghastly cell, it was a startling image. No dramatic Parisian beauties dressed in black, smoke coiling from their ruby lips; no jaded young men with scarves wrapped tight around their necks; no Algerian cab drivers pretending to know the their way, boasting as they drove in circles around the sullen, industrial neighborhoods at the southern edges of the city. Nothing human, not a soul: only the buildings, but even they were somehow changed. In his reverie, he squinted: what was it? Windowless, he could see it now, a city of tomb-like structures. Everything bricked-over, monuments too encased in concrete, as if the city had, for its protection, buried itself block by block, neighborhood by neighborhood. Denuded trees stood like skeletons along the Seine. A city of multiple Chernobyls. The images played out before him in high definition: first the dead city of his birth, then his family, at the pier in Dakar, scanning the horizon for a boat from America that would bring their youngest son home again. He wept at the thought of it. The ocean is turbulent, and ships do not carry Africans east across the Atlantic.

Will you be disfigured, Mr. President?

You will.

But allow me to interpret: aren’t we all mere vessels, carrying on our persons the sundry wounds and scars of living? Is not the very character of a man molded in his darkest moments? And yet, you can count yourself fortunate: times have changed since Private Thomas A. Perrine of the Michigan Regiment (Union) penned these melancholy verses:

I offered her my other hand

Uninjured in the fight;

‘Twas all I had left.

‘Without two hands,’ she made reply

‘You cannot handsome be.’

War has left me with empty sleeve,

but she, alas, with empty heart.

The First War of Rebellion is in the distant past. A great variety of cripples are now allowed in polite company, and marriages these days are constructed of firmer stuff, are they not? The treachery of a woman such as is described in the poem is not oftentimes seen in our day. And in your case, dear sir, stories of your wife’s devotion have reached Paris, I assure you.

But let us look upon your potential disfigurement another way: think of the level of solidarity you will have achieved with the soldier who is now waging war against the insurgency! In your name! The disfigured veteran will see in you a picture of himself, a veritable monument to his service.

The President asked that his leg be brought to him. “One way or another,” he said. The order shivered its way through the great brain of government. The next day, secret service agents were kicking in doors in Brooklyn, rousing migrant farm-workers from their sheds in the fertile valleys of California, and tearing through mountain cabins in Appalachia. They looked in schools and factories, patted down office workers cubicle by cubicle. The newspaper offices were bombed. While the great cities of the nation fell into protest and chaos, the Army marched through the forests of Oregon with chainsaws. They cannot hide, Mr. President.

But the subversives had vanished. The leg as well. There was a network of sympathizers, people said, all over the West. Denver was theirs. They were preparing to bring the war east. Forget your leg, the President’s advisers told him, it could be anywhere in the vast hinterland. In a cave, they said. Anywhere.

“You’ll feel better once you execute the African,” his advisers said.

“I thought he was French,” the President said.

That evening, the eastern power grid failed. There was looting in New York, riots in Boston. In a White House lit by candles, the President lay with his wife. Who was he kidding? The country was quite obviously falling apart. The government army was in disarray, camped outside Denver awaiting orders. The disasters were multiple and hideous. He felt a pang in his right leg and his heart leapt, but he looked down on the stump and felt the terror of recognition.

The President’s wife massaged his stump. She wrapped it in warm towels. He fought back tears. The room shone orange in the candlelight. “I am a failure,” he said.

Oh, dutiful First Lady! “Mr. President,” she purred. “Mr. Commander-in-Chief!”

“You’re the next Lincoln!” she cried.

Céphas was received in the Lincoln bedroom. Guards stood at the door. The First Lady lay on the bed reading. “It was good advice,” Céphas said, when confronted. “Sound medical advice and I stand by it.”

In his wheelchair, the President registered pure hatred.

Céphas felt his face flush. “No, no,” he apologized, “a clumsy choice of words, Mr. President, I beg you. My English is not so good.”

“Your reports have arrived,” said the President. “Your English is fine.” He threw a stack of papers at the African. They spilled like confetti over the carpeted floor.

In his cell, Céphas dreamed of Paris, and his jailer dreamed of Salisbury Steak. The jailer’s name was Jackson and he liked to tell everyone that his wife Mae, “could really hook up dinner.”

Jackson got hungrier as the night wore on and so to pass the time, he and another guard pulled Céphas from his cell and beat him. Jackson liked to beat prisoners and imagine himself being videotaped, starring in a television special on rogue cops, and maybe have the videotape set to music, something dark and bass heavy. Céphas wailed as they kicked him. Jackson tried out soundtracks in his head: the taut snap of a snare drum, the metallic splash of cymbal! Bongos, congos, juju music! Jackson shouted at his prisoner and felt he was flying.

His soul was stirred beyond all reason and he could walk on hot coals or handle poisonous snakes—surely he could!

Instead, he pulled his gun instead and shot the African doctor. The loud clap of the weapon echoed in the cell and silenced the music. Paris went black.

The room was thick with catastrophe. Jackson’s partner was already on the walkie-talkie, calling someone to do something about what had just happened. “Well, what’s happened?” the voice on the other end asked. Jackson could barely hear his partner. “I don’t know,” he was saying. “Hurry up and get down here.”

Now that the Second War of Rebellion has begun, Mr. President, it may be instructive to review a case history from the first such war. Again, you will take solace in the outcome. Case #3354, 1863: Private Henry Robinson of Louisiana (Rebel) Regiment, aged 35 years, was wounded at the confluence of the Tallahatchie and Yalobusha Rivers on March 13 by a fragment of a twenty-four pound shell fired from United States gunboats. Surgeon William M. Compton was standing near the wounded man when he fell. Hastily exposing the wound, Dr. Compton found that the immense projectile had buried itself in the upper part of the left thigh, smashing the trochanters and neck of the femur and wounding the femoral artery. The necessary preparations were made on the spot. Chloroform was administered. Dr. Compton made an irregular incision just above the lacerated margin of the wound and dissected upwards, retracting the skin and trimming away the muscles.

Soldiers in those days—even rebels—were hardened men, unafraid of death. When the anesthesia had passed away, the patient was cheerful, even jocular. The stump was covered with yeast poultices. Beef essence, stimulants and anodynes were also administered. However, within two days, there was yellowness at the surface and pus of a very offensive nature, though the lips of the wound were united in nearly their entire extent. Need I say the patient did not rally? Smile, Mr. President: another rebel dead, a victory for human progress: first came delirium, then coma, and then death!

There is an argument on the floor of the Congress. Listen: “If the good gentleman from Arizona has no further answers for the Committee, will he kindly yield the floor?”

“I will not,” said the Engineer. He was red-faced and angry. “I will not,” he said again, and bared his teeth. There it is, he thought, I’ve done it: I have growled at the Speaker of the House on national television. It’s about fucking time, he thought. A flurry of cameras flashed and clicked. They were asking him questions about things he knew nothing of: who were these supposed suicides? Did he know anything about the death squads that had been dumping bodies in the lake? Had he ordered the killings himself?

The dam had been bombed. The lake had grunted and spilled. Who cares about death squads? Isn’t there a war going on?

How did the President’s leg wind up in your lake, Senator?

“It’s not my lake,” he said.

The leg had been found that morning in the drying sludge of the lakebed. It had been rushed to the lab, badly decomposed, for DNA testing.

The Engineer wondered where it had all gone sour. By today, of course, it was far too late to salvage anything from the sick nation. But yesterday? Last week? A year ago? A decade? Or was the moment of our fatal turn buried somewhere farther in the distant past? When the nation was only an infant, learning to crawl? Who were these people questioning him, and by what right? His inquisitors did not smile. Did they want contrition? Did they expect groveling? They’ll have their spectacle if they want it! His teeth were still bared.

“Senator, please!” they shouted, but he couldn’t stop: he felt a blood vessel might explode. His teeth poked like fangs from his open mouth; he imagined them sharp and ferocious. “In a moment the power will go out,” he shouted, “and I’ll bite the first man who lays a hand on me!” The Engineer was an animal after all, bounding from table to table on all fours, his hands bent into claws. The Engineer’s suit seemed to come apart at the seams, his chest swelling. Beneath the gilded dome of the Capitol, he roared like a lion.

What did these men dream of, Mr. President, when death eclipsed them? When they marched a full winter’s day with a rotting wooden crutch? When they joked, legless, with their doctors in an opium daze? When they swallowed in suicidal mouthfuls the blue waters of Arizona’s artificial lake? Did they dream of love and women, of family and friendship? I submit that if they were soldiers, true warriors, they did not waste their dying moments with such maudlin concerns. If they were warriors; indeed, if they were men, they dreamed only of vengeance. This is the lesson you must take with you, the lesson you must weave into your heart.

It will lead you forthrightly into battle. Now ask yourself: do I trust this doctor? You must and you will. Everything will proceed like this: the first incision must be precise, or else all is lost. I cannot hesitate even for a instant without risking hemorrhage. I will take the scalpel and press its blade firmly against your skin, and slice as if I were cutting into an apple or a steak. Like a warrior, I must be merciless. Infection and disease are the enemies at the gate. Yes, there will be blood, but am I not a surgeon?

Presidential blood is the same as any other, dear sir, the same shade of red, the same sticky consistency between the fingers. It can be spilled, as surely the earth can soak it up. Only joking. I will take the scalpel and I will cut you. Really, it isn’t so dramatic. Don’t worry over the blood, and never mind the bone. It will be sawed through, disarticulated. Your femur is destroyed; there are no options. See how easily the skin pulls back? Surgery is a species of murder. You must be calm. I will finish and go home, and leave you to lose your war. Godspeed. Inshallah. I will finish and marry three wives. You will feel no pain, not until later, but then, aren’t you a man? You have suffered for months with this wound and I will relieve you of it. You will be sedated, asleep and dreaming in Technicolor, eyes darting about beneath the lids, beatific as I cut you. And of course, no one will know anything, Mr. President. These are state secrets.

[Note: some material adapted from Amputations at the Hip Joint: A Study, published by the War Department, Washington D.C. 1867 and Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs by Alfred J. Bollet. Tucson: Galen Press, 2002]

Previously Printed by Konundrum Engine Literary Review

Daniel Alarcón hails from Lima, Peru. His short stories have appeared in The New Yorker and other magazines.