Find me in the room midway between life and death, she said. Her hair wrapped in a rope of clouds tied to the sky. Her neck bent by a man’s hand, her tongue suspended, one eye hidden, and an old man trying to mine her mind. Men tried to write her for a century, and other eternities. Their head spun in place. Their rage so loud she stopped hearing it. Telephone wires ran through her body and tugged her in different directions the way exile does. The way the world falls and the sea begs when love limps. The way numbers climb the wind like death tolls when oppressors are free.

The dead always come alive if they didn’t die right. An Andean Condor came and stared. The walls sweating blood. Suddenly they appeared: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Manuelita Sáenz, Juana Azurduy de Padilla, La Pola, Paixão Pagu, Tania La Guerrillera, las hermanas Mirabal, las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, las Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo—speaking the myths, loading their words, and singing songs she hadn’t discovered yet: No one will tell you where the water begins in your body nor where the blue gets bluer. It’s a question of power. Explore the ruins. Draw the maps of deaths and damages and desires. Dive into her deep. Deep into her erotic. Discover the way back to her dream, your dream, and we will never disappear. After that, when men tried to strip her clothes off, her sexiness off, her luminance off, she stared at them. An amaranthine stare.

Imborrable

por Nathalie Handal ~ Traducción de Kianny N. Antigua

Encuéntrame en la habitación a medio camino entre la vida y la muerte, dijo. Su pelo envuelto en una cuerda de nubes atadas al cielo. Su cuello doblado por la mano de un hombre, su lengua suspendida, un ojo oculto y un viejo tratando de excavar su mente. Los hombres intentaron escribirla durante un siglo y otras eternidades. La cabeza les dio vueltas. Su rabia, tan fuerte, que ella dejó de escucharla. Los cables del teléfono recorrieron su cuerpo y la tiraron en diferentes direcciones, como lo hace el exilio. De la forma en la que el mundo cae y el mar suplica cuando el amor cojea. De la forma en la que los números trepan por el viento, como la cifra de muertes cuando los opresores son libres.

Los muertos siempre cobran vida si no mueren de la forma correcta. Un cóndor andino se acercó y observó. Las paredes sudaban sangre. De repente aparecieron: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Manuelita Sáenz, Juana Azurduy de Padilla, La Pola, Paixão Pagu, Tania la Guerrillera, las hermanas Mirabal, las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, las Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo, hablando los mitos, cargando sus palabras y cantando canciones que ella aún no había descubierto: nadie te dirá dónde comienza el agua en tu cuerpo ni dónde el azul se vuelve más azul. Es una cuestión de poder. Explora las ruinas. Dibuja los mapas de muertes, daños y deseos. Sumérgete en su profundidad. Profundo en su erótica. Descubre el camino de regreso a su sueño, a tu sueño, y nunca desapareceremos. Después de eso, cuando los hombres intentaron quitarle la ropa, su sensualidad, su luminosidad, ella los miró fijamente. Una mirada de amaranto.

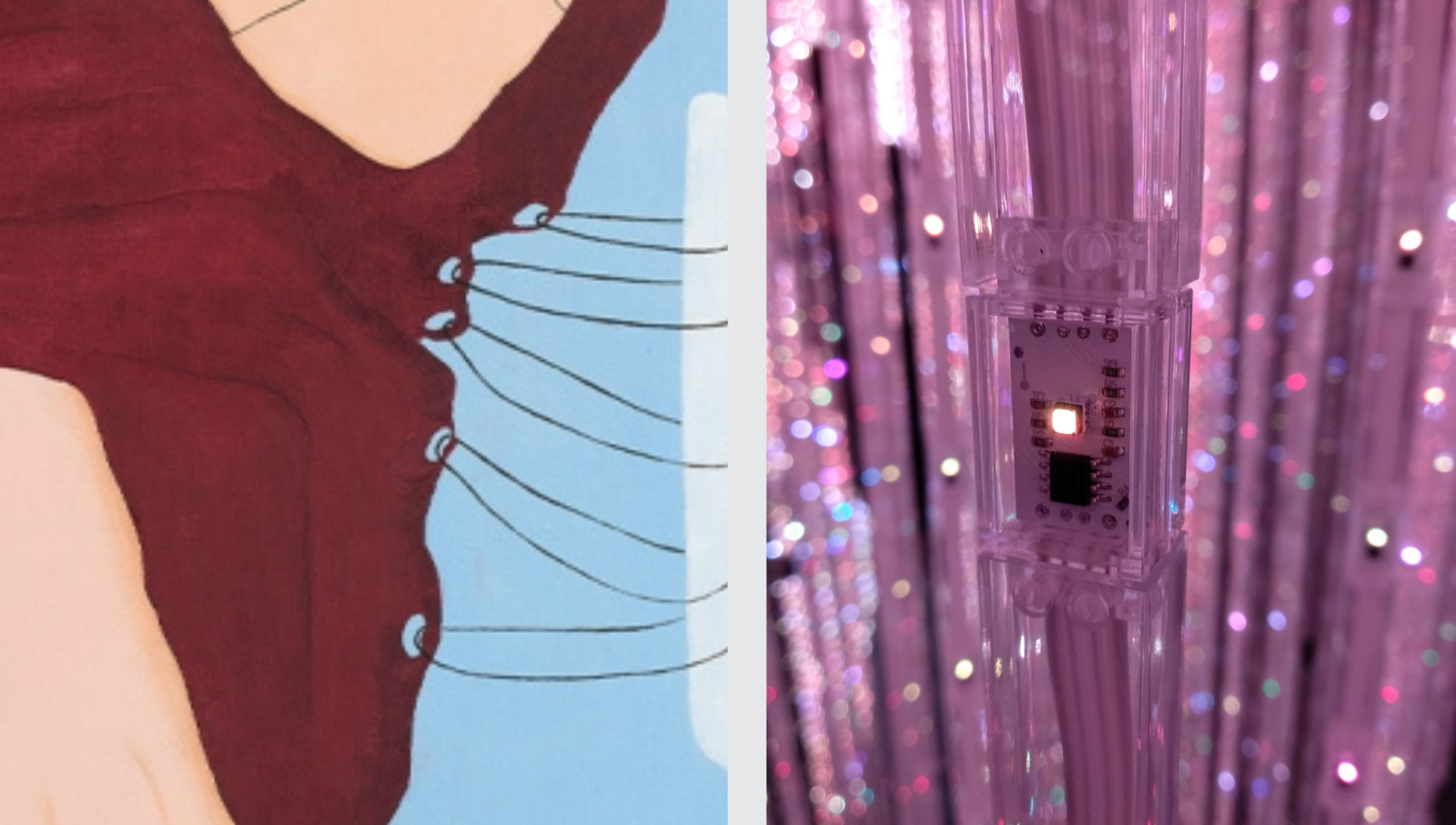

This piece is from our Winter 2021-2022 in-residency series, The Amaranta Project.

Nathalie Handal is described as a “contemporary Orpheus.” She is the author and/or editor of 10 award winning books, including Life in a Country Album, winner of the Palestine Book Award; the flash collection The Republics, lauded as “one of the most inventive books by one of today’s most diverse writers,” and winner of the Virginia Faulkner Award for Excellence in Writing and the Arab American Book Award. Her nonfiction has appeared in Vanity Fair, Guernica, The Guardian, The New York Times, The Nation, and The Irish Times, among others. Handal is the recipient of awards from the PEN Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, Fondazione di Venezia, Centro Andaluz de las Letras, and the Africa Institute, among others. She is professor at New York University, and writes the literary travel column, “The City and the Writer” for Words without Borders magazine.