To open Albert Abonado’s latest poetry collection is to be greeted with mouthwatering flavors. Ginger. Garlic. Bitter melon. Bay leaf, vinegar, a plate of rice. Mango, grapefruit, and honey; lumpia and pineapple. Fried chicken and banana leaf. In these poems, food is more than physical sustenance—it is a language of memory and resistance, passed down through generations.

Abonado invites readers to take a seat at a table where family stories, prayers, and silences are spun into daring, intimate poems. With boldness and clarity, he confronts the complexities of the body, identity, and the personal and political forces that shape them. Field Guide teems with life, indulging in its sights and smells. At once voracious and edible, poems, for Abonado, “chew / on your cuticles” with a “mouth full of heirlooms”; they are tasted, swallowed, left to “nest in the guts.”

Throughout the book, the body is carefully attended to. Here, it seems that attention given to the body is not just a form of love, but love itself. Love is pulling white hairs from a father’s scalp; it is washing and moisturizing one’s face. It is a lover’s lips on the nape of the neck, or a home-cooked meal scooped up by one’s fingers, enabling the body to keep moving and breathing. In poems like “Mano,” Abonado elevates these small, seemingly mundane actions to sacred rituals: “If I perform a gesture enough / times, it turns into a holy reflex,” he writes of the unspoken acts that bind us to each other and to ourselves.

But what happens when attention is withheld—or given in unequal measures? Field Guide is acutely aware of the larger forces that neglect the body on a systemic level. Abonado examines the inattention of the state, its inability to love, and the ways in which this disregard leads to tragedy and injustice. Certain bodies are reduced to consumables, their needs ignored; are criminalized and denied the right to rest, care, and safety. In the title poem, Abonado scrutinizes the crisis of sleep deprivation and its psychological and physical tolls, particularly on marginalized groups. “White people sleep better and longer in America,” he writes, pointing to the accumulation of inequalities that make people of color more vulnerable to fatigue, violence, and erasure.

At the heart of the collection lies Abonado’s personal and familial history, particularly a car accident that becomes a central anxiety throughout the book, informing the poet’s sense of fragility and loss. The act of remembering becomes a way of honoring those who raised him and came before him. Abonado takes on the role of witness and family archivist, attentive not only to sight but to all of the senses. He remembers cradling his father’s head in his lap as he plucks out his white hairs, the smell of soil under his father’s fingernails, the way he hums while driving.

Of his mother, he recalls the sound of her bones grinding beneath her skin as she prays in the garden after surgery, and pictures himself “inside the smoke and rice of her story.” This commitment to memory seems to be one of the central tasks of Field Guide, throughout which Abonado catalogs the tenuous, perishable things of life: food, poetry, loved ones––that which is flesh and fleeting, like most things worth cherishing or praising.

Reading Abonado’s poems, some of my own memories resurface and sharpen. One, in particular, stands out: my mother sitting beside me, clipping and filing my fingernails, even though I was, by then, old enough to do it myself. The adolescent part of me, itching for independence, wanted to resist her touch, to pull my hands away from hers. But together, we yielded to this ritual, one we had shared all my life. I am lucky to carry that gesture of care with me. To know such love, Field Guide reminds me, is often enough.

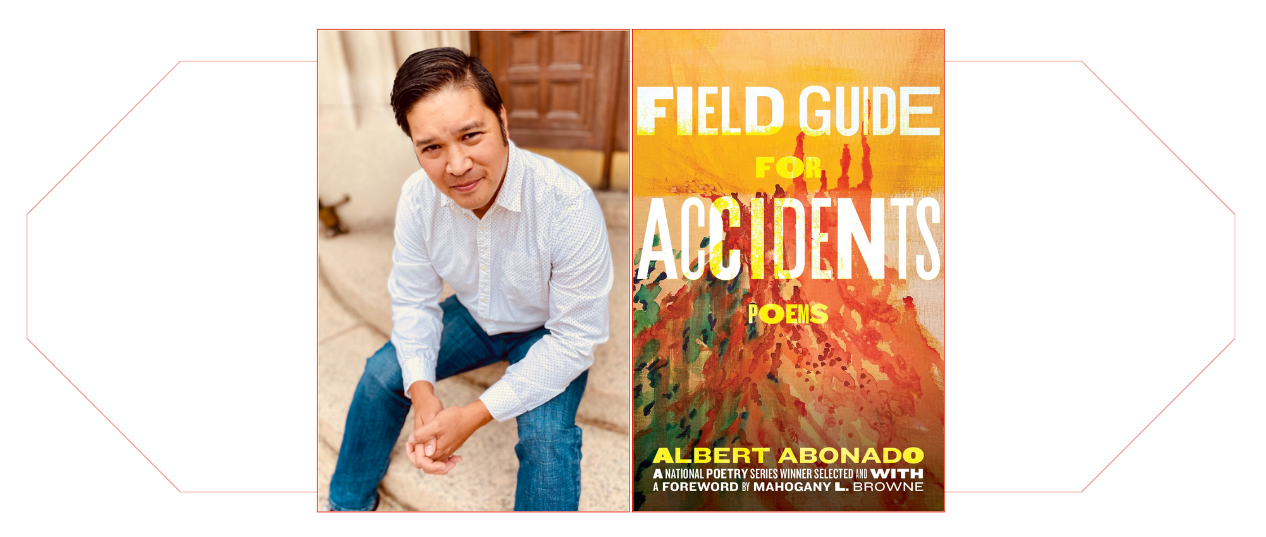

Photographs courtesy of the author’s website.

Aya Burton is an MFA student at the University of Pittsburgh. She is currently writing about memory, desire, and mollusks.