We climb toward the rumored grave

of an Native American healer, the earth

a vertigo of blackness and exposed

root beneath our palms, pressing up

through the waves of molten leaves,

toward the bluff where our children,

having for the past hour pretended

not to hear our demands for them

to come down, are now balancing

their sun-licked, baby-fat-all-but-gone

bodies, on a thin shelf of rock. “Look,

it’s a deer! A deer in a wolf ’s face!”

their cries tumble down, snagging

like runaway rags on the branches;

they look like Brutus and Cassius

debating the fate and meaning of

a red stain the size of a man etched

into granite, commanding the speech

of minerals – they’ve found a myth

worth more than their mothers’ fear.

The wind makes a bear of me, gristling

my chest and thighs as I crawl, gravity

inhaling me like an enormous throat,

over the deadness of trees and thorned

bushes, knuckles bursting like berries,

thoughts detritus around a New York

Post article I read about a woman, who

weeks ago, her brain sweaty with prayer,

climbed the rope of her body, her black

body, up the steepest mountain in America,

which rose between the door of her car

where her children rocked each other

in the arms of the storm, and the door

of the house she knocked and knocked,

until her knuckles burst into mouths,

her body a black tongue, a root burning

against which the family in the living room

drily surveyed their possessions:

fine china, paintings collected over

the years, utensils gleaming in candlelight,

the life-size television – their window

into loss and destruction – which

is silent now, their sleeping Noah.

The door did not open. The animals in

the house survived, while two baby boys

washed away, their screams became

the moulted skin of water as it bucked,

roiled against its own vanishing empire,

claiming for days a solid mass, blitzkrieg

of porches and tire swings, of libraries,

the vowels of a child’s eyes looking up

at the body that broke open for him

and keeps breaking, like a faulty dam,

even after water returns to water, lifting

like souls in sunlight, to form the clouds

that now drift above us, waiting their turn

to kiss the mouth of a forgotten grave,

the red of a mother’s heart. I hold my son

to me, I breathe him, and try to witness

the miracle of leaves still clinging

to branches, scrawling their petitions

on the November breeze – even as we

stare at our knuckles, the ripe strength

of them, on this precipice we have been

led to in the wake of the flood, asking

the gods, which do we raise them to be:

deer or wolf? The dead give nothing away.

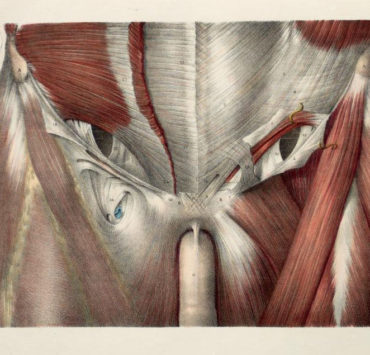

Image Credits: Several Second

Cynthia Dewi Oka is a poet and author of Nomad of Salt and Hard Water (Thread Makes Blanket, 2016). A Pushcart Prize Nominee, her poems have appeared online and in print, including in Guernica, Black Renaissance Noire, Painted Bride Quarterly, Dusie, The Wide Shore, The Collapsar, Apogee, Kweli, As Us Journal, Obsidian, and Terrain.org. She is also a contributor the anthologies Read Women (Locked Horn Press, 2014), Dismantle (Thread Makes Blanket, 2014), and Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Frontlines (PM Press, 2016). Cynthia has been awarded the Fifth Wednesday Journal Editor’s Prize in Poetry, scholarships from the Voices of Our Nations (VONA) Writing Workshop and Vermont Studio Center, and the Art and Change Grant from Leeway Foundation. An immigrant from Bali, Indonesia, she is now based in South Jersey/Philly. Her second poetry collection is forthcoming in 2017 from Northwestern University Press.