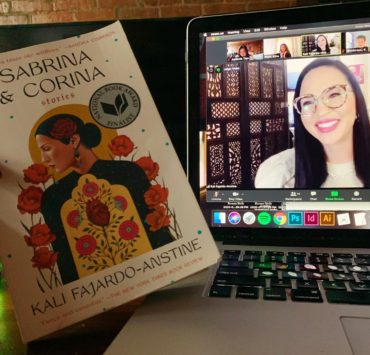

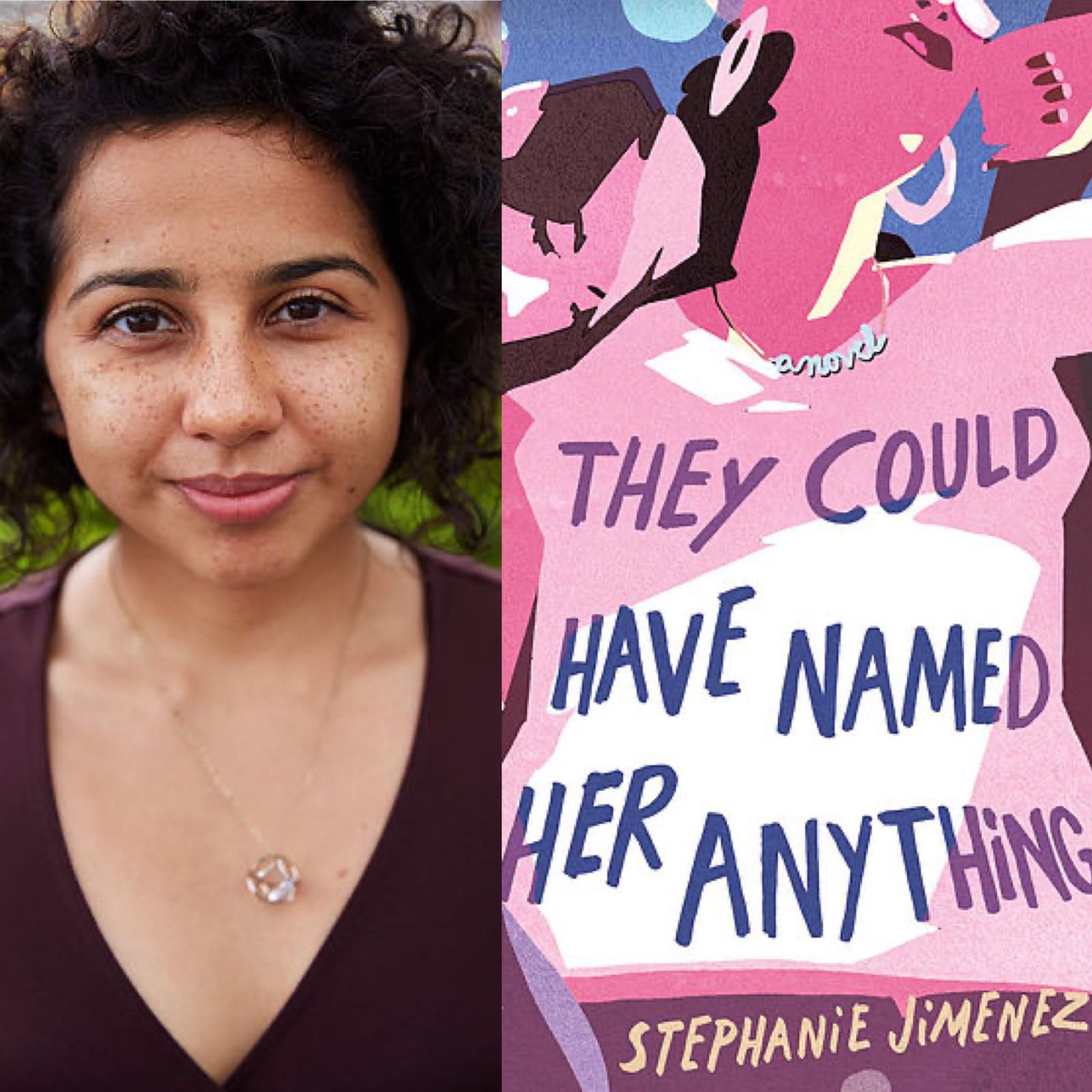

Angie Cruz meets with Stephanie Jimenez, author of They Could Have Named Her Anything to discuss her book.

AC: I appreciate the title of your book so much. Can you tell me more about it and how it addresses cultural interchangeability?

SJ: I grew up in New York City, but when I applied to colleges in California primarily, I ended up going to an all-women’s college, on the west coast in California, like Southern California. All of my friends were Mexican-American, and one Guatemalan. But mostly, people from Central America and Mexico. It was the first time that I really was able to experience cultural pride. I didn’t know what Chicano meant before then. I didn’t really know the history of Mexicans in that part of the states. We all got together on a weekly basis at this club that was called Café con Leche. No one really even cared or asked where I was from. We all bonded over the fact that we were Latinas in a majority white setting. That made an impression on me. A kind of solidarity that I had not seen growing up in New York. I grew up in a place where people very much held on to where they were from, and sometimes in a negative way, sometimes as a way to position oneself as being superior or inferior to another Latino subgroup. And that’s what I hope to evoke in using this more general concept of interchangeability. It’s not just a way for white people to not see us, but as a way for maybe, for us to just start, you know, being willing to reach out to each other more.

AC: I liked how you dealt with class in the book. There’s this amazing scene at the boarding school where Maria, she’s going to this private school on the Upper East Side, and she’s at this diner, and I feel like it’s such a New York moment, because here she is with no money. She has like $1, and everyone’s ordering whatever they want at the diner. She knows she can’t pay for it. Her friends says, “Oh, I’ll pay for everyone.” And then another person’s like, “No, we’ll split the check.” And of course Maria is dying inside. She knows she won’t be able to pay for it. Did you know early on that your book would focus so heavily on class differences?

SJ: I absolutely wanted it to be very much a New York story about class, about the differences between the people who live here. I think there’s still a conception—even though a lot of people have disproven this— that New York City is this big melting pot, and that we’re always coming into contact with each other. We do have a really diverse city, and Queens, where Maria is from, is one of the most diverse places in the world. But the amount of contact that we actually have across communities and across classes is pretty limited. Look at our school system, and how certain neighborhoods or zones are assigned to certain public schools. This creates segregated system where the poorest students of color live in one place, and the white wealthy majority move around wherever they want. That was always important to me, because it’s been such an essential part of the way that I understand New York City, in that we are still quite segregated. Even though we too have access to everything. On its face, it looks that way, but we actually don’t.

AC: I’m curious about your writing practice and genre. You wrote a novel, but you also write mini essays. And before you wrote this novel, you were working on essays that you published in different journals and magazines. Why the novel? What can the novel do that other genres can’t?

SJ: I can be way more playful in the novel. I write essays because I hear it’s good for publicity. But yeah, I think that there’s just so much more freedom, in writing fiction, and exploring things in fiction. I wrote from the perspective of two men in the book, and that would not have been possible if I had written a memoir.

AC: Did you discover anything that surprised you?

SJ: I think that being part of writing groups, and before this became the book that it is, is always a process in challenging what you believe about the world. And so I have learned a lot in terms of the way that I depict people like characters that are so far from my own experience of life. I think the scary and exciting part about writing fiction: you never really know if you’re going to get it right.

AC: What are you thinking about and working on now?

SJ: I’ve been thinking about the difference between community and individualism. I spent a year living in Colombia. My mother was born there, and when I graduated college, I wanted to see the place where half my family came from; I had never been there before. I accepted a Fulbright to live there for a year. It was a learning experience, in many ways. But one of the things that I came away from that time was that how different the culture was in terms of sharing things with people, looking out for one another, and there was this sense of family. There are men who are like 30 years old, who are still living with their parents. And I was like, “Huh? I wouldn’t do that.” I’m interested now in exploring this difference between what I found to be such a community and community-oriented culture versus what in New York City in particular is so focused on individualism and making your own way, standing out and being your own person. I think there’s a lot of literature by people of color that explores the idea of a community and intergenerational family and our origins. For my next project I want to explore what it means to have the sort of freedom a lot of Americans who don’t come from marginalized backgrounds have, in being an individual and how that differs, I think for people of color.

AC: You brought up the word freedom. I’ve been interested in this. Aster(ix) recently published The Ferrante Project, where we invited writers to produce works anonymously. It was an invitation to play and free ourselves from what is expected either because of notoriety or fame. Where are the spaces of freedom in your work or practice? Where do you hope to be freer?

SJ: It’s a hard question, because I don’t know that I’ve found it yet. The first place I would want to start is just changing what publishing looks like. I worked briefly in the industry, and the overwhelming whiteness that I felt on the day to day basis that I think shaped what I thought I could do with a novel or work that I could publish. So, I would start with that. I would also hope that one day, there is Costa Rican Literature to write into. The fact that there is even within the label “Latina writer” “Latino writer”, the fact that there are some that feel have more of a tradition in the states. I wish there was more community I could find with more background like mine in the states. But again, I would also like the freedom to not have to always think about it.

Stephanie Jimenez is based in Queens, New York. Her fiction and non-fiction have appeared in the Guardian, O! the Oprah Magazine, Joyland Magazine, The New York Times, and more. She is a former Fulbright recipient and a graduate of Scripps College in Claremont, California. Her debut novel, THEY COULD HAVE NAMED HER ANYTHING, was published on August 1, 2019 (Little A).

They Could Have Named Her Anything is available for purchase here.

Angie Cruz's novel, DOMINICANA is the inaugural bookpick for GMA book club, and the Wordup Uptown Reads selection for 2019. It was also longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie award in excellence in fiction for 2019. It was named most anticipated/ best book in 2019 by Time, Newsweek, People, Oprah Magazine, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Esquire. Cruz is the author of two other novels, Soledad and Let It Rain Coffee. She's the founder and Editor-in-chief of the award winning literary journal, Aster(ix)and an Associate professor at University of Pittsburgh where she teaches in the MFA program. She splits her time between Pittsburgh, New York, and Turin.